Emergency Mgmt 2.0: How #Socialmedia & New Tech Are

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Google Testimony Homeland Security Crisis Response Hearing 5-5-2011

Testimony of Shona L. Brown, Senior Vice President, Google.org Before the Senate Homeland Security Ad Hoc Subcommittee on Disaster Recovery and Intergovernmental Affairs Hearing on “Understanding the Power of Social Media as a Communication Tool in the Aftermath of Disasters” May 5, 2011 Chairman Pryor, Ranking Member Brown, and Members of the Committee. Thank you for your focus on the important issue of crisis response and the central role that technology now plays in disaster relief and recovery. During the past year, tens of millions of people around the world have suffered through natural disasters such as earthquakes in Haiti, Japan, Chile, China, and New Zealand; floods in Pakistan and Australia; and forest fires in Israel. Our own citizens have faced crises, with tornadoes and floods causing terrible damage in recent weeks reminding us of the toll natural disasters have on human life. Our thoughts are with the communities that have just been hit by devastating tornadoes in Alabama and across the US. As the Senior Vice President of Google.org, the philanthropic arm of Google, which includes the team that responds to natural disasters around the world, I have seen the increasing importance of Internet-based technologies in crisis response. Our team has used search and geographic-based tools to respond to over 20 crises in over 10 languages since Hurricane Katrina, and we have already responded to more crises in 2011 than we did all of last year. In the aftermath of the devastating tornadoes in Alabama last week, we supported the Red Cross by providing maps that locate nearby shelters, updated satellite imagery for first responders, and directed local users searching for “tornado” or “twister” to the maps through an enhanced search result. -

Old Sturbridge Village Receives $5 Million Bequest

Family owned & operated for 59 years! Guzik Motor Sales Inc. Spring into “Car buying the way it should be!” SAVINGS! Check our website for gimmick-free prices 2021 Jeep Wrangler 2021 Grand Cherokee 95 E. Main St., Rtes. 9 & 32, Ware Just Over The West Brookfield Line 413-967-4210 or 800-793-2078 Come in and visit or browse our lineup at: www.guzikmotors.com Free by request to residents of Sturbridge, Brimfield, Holland and Wales SEND YOUR NEWS AND PICS TO [email protected] Friday, March 12, 2021 Marshalls donates goods to United Way STURBRIDGE — Facemasks make a difference, and Marshalls, located in Sturbridge donated more than 2,000 child and adult masks and hand sanitizer to be distributed to non-profits that are affiliated to the United Way of South Central Mass. (UWSCM), along with local food pantries and elementary schools. Paul Sullivan, Administrative Coordinator. At the Sturbridge Marshalls, contacted the United Way stating TJX Company stores, which Marshalls is one, were removing masks and hand sanitizer from their shelves and they would like them to be donated to local charitable organiza- tions. Mr. Sullivan thought of the United Way of South Central MA as a perfect recipient since UWSCM has 22 member agencies that assistant many children from toddlers to teens and adult programs that could benefit from these donat- ed goods. Mr. Sullivan and Brittany Vescovi, Assistant Manager met Mary O’Coin, Executive Director of UWSCM with 11 boxes of donated sup- plies outside of the Marshall’s in Sturbridge. Mrs. O’Coin was completely surprised by the number and quality of the masks that were donat- ed. -

Post-9/11 Veterans the American Legion Soon Belongs to Our Second-Century Veterans

CONNECTIONS the American Legion Post-9/11 Veterans The American Legion soon belongs to our second-century veterans. As the nation’s largest veterans service organization reflects on a legacy of historic achievements and millions of lives positively influenced, now is the time to envision a future guided by 21st century veterans, their families, communities, needs and interests. More than 2.7 million Americans have served in the Iraq and Afghanistan war zones, many on multiple deployments. This Post 9/11 "I feel the post-9/11 generation generation of wartime veterans is a fast-growing segment of American certainly has an identity. Legion membership and leadership. In many communities, the ice breaker between the traditional post and younger veterans is a relationship with We responded to a national tragedy. such groups as: We all volunteered. We volunteered for - Team Red White & Blue - Student Veterans of America a decade of war. We had options, - Team Rubicon and we chose this. Our vision is to show - The Mission Continues Local posts, districts and departments also build relationships of their the world what we can do. own with regional groups of young veterans, with specific interests. We can kick ass. We can face anything. Among them are Veterans in Film and Television in Los Angeles and Summit That's our vision going forward." for Soldiers, which is based in Ohio and has expanded to other states. The American Legion, with more than 13,000 local posts worldwide and Chris Wilkens, a U.S. Marine Corps veteran a Legion Family membership network of more than 3 million, has much to who fought in the Battle of Fallujah during Operation Iraqi Freedom who now leads a 1919-chartered American Legion post offer these groups, including physical meeting spaces, business networking, in the New York Athletic Club overlooking Central Park in Manhattan mentorship and experience in community service projects. -

A FAILURE of INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina

A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina U.S. House of Representatives 4 A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Union Calendar No. 00 109th Congress Report 2nd Session 000-000 A FAILURE OF INITIATIVE Final Report of the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Report by the Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoacess.gov/congress/index.html February 15, 2006. — Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U. S. GOVERNMEN T PRINTING OFFICE Keeping America Informed I www.gpo.gov WASHINGTON 2 0 0 6 23950 PDF For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-0001 COVER PHOTO: FEMA, BACKGROUND PHOTO: NASA SELECT BIPARTISAN COMMITTEE TO INVESTIGATE THE PREPARATION FOR AND RESPONSE TO HURRICANE KATRINA TOM DAVIS, (VA) Chairman HAROLD ROGERS (KY) CHRISTOPHER SHAYS (CT) HENRY BONILLA (TX) STEVE BUYER (IN) SUE MYRICK (NC) MAC THORNBERRY (TX) KAY GRANGER (TX) CHARLES W. “CHIP” PICKERING (MS) BILL SHUSTER (PA) JEFF MILLER (FL) Members who participated at the invitation of the Select Committee CHARLIE MELANCON (LA) GENE TAYLOR (MS) WILLIAM J. -

COVID-19 Conversations Webinar #8 Transcript

1 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF MEDICINE and AMERICAN PUBLIC HEALTH ASSOCIATION + + + + + SUMMER OF COVID-19: MITIGATING DIRECT AND INDIRECT IMPACTS IN THE COMING MONTHS + + + + + WEBINAR + + + + + WEDNESDAY MAY 27, 2020 + + + + + The Webinar convened via video teleconference, at 5:00 p.m., Nicole Lurie, Moderator, presiding. 2 PRESENT GEORGES C. BENJAMIN, MD, Executive Director, American Public Health Association NICOLE LURIE, MD, MSPH (Moderator) --- F o r m e r A s s i s t a n t Secretary for Preparedness and Response at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Co-Chair, COVID-19 Conversations advisory group LINDA DeGUTIS, DrPH, MSN --- Adjunct Professor, Emory University Rollins School of Public Health; Lecturer, Yale School of Medicine CRAIG FUGATE --- Former Administrator, Federal Emergency Management Administration; Former Director, Florida Emergency Management Division ATEEV MEHROTRA, MD, MPH --- Associate Professor of Health Care Policy and Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center physician KENT SMETTERS, PhD --- B o e t t n e r C h a ir Professor at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School, Faculty Research Fellow at the National Bureau of Economic Research, and Faculty Director of the Penn Wharton Budget Model 3 CONTENTS Welcome and Introduction Georges Benjamin ........................ 4 Nicki Lurie ............................. 6 Coronavirus Policy Responses Kent Smetters .......................... 11 The Pandemic's Impact on How Americans Get Care Ateev Mehrotra ......................... 27 Managing Concurrent Emergencies Craig Fugate ........................... 37 Data Regarding Spikes During Disasters Linda DeGutis .......................... 47 Question and Answer.......................... 59 Final Words.................................. 86 Adjourn...................................... 94 4 P-R-O-C-E-E-D-I-N-G-S 5:00 p.m. -

September 18 at 7:30Pm

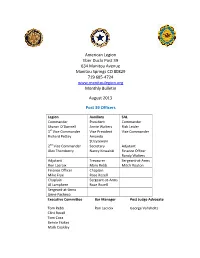

American Legion Eber Duclo Post 39 634 Manitou Avenue Manitou Springs CO 80829 719 685-4724 www.manitoulegion.org Monthly Bulletin August 2013 Post 39 Officers Legion Auxiliary SAL Commander President Commander Sharon O’Donnell Annie Walters Rick Leider 1st Vice Commander Vice President Vice Commander Richard Pettey Amanda Strzyzewski 2nd Vice Commander Secretary Adjutant Alex Thornberry Nancy Kowalski Finance Officer Randy Walters Adjutant Treasurer Sergeant-at-Arms Ron Lacroix Mary Rebb Mitch Routon Finance Officer Chaplain Mike Frye Rose Rozell Chaplain Sergeant-at-Arms Al Lamphere Rose Rozell Sergeant-at-Arms Gene Pacheco Executive Committee Bar Manager Post Judge Advocate Tom Rebb Ron Lacroix George Vahsholtz Clint Rozell Tom Coca Bernie Frakes Mark Coakley Hours of operation: Saturday and Sunday: 1pm to closing Monday, Thursday and Friday: 2pm to closing Tuesday and Wednesday: Post closed American Legion Post 39 News and Happenings Next General Membership meeting is Wednesday, September 18 at 7:30pm. Next meeting of the Executive Board is Tuesday, September 10, at 6:30pm. 2014 Membership Renewals 2014 membership renewals are well underway. Members renewing on or prior to Friday, 9/27, are eligible to take part in the Early Bird Steak Dinner. If you have already submitted your membership renewal, thank you. For those members not yet renewed, support your Post now and in the future by getting those renewals in as soon as possible. Volunteers from Post 39 responded admirably to the recent devastating floods in Manitou Springs. Mike and Amanda Strzyzewski and Billy Fine assisted residents in clearing mud and debris left by the flood. -

Team Rubicon

Team Rubicon Our use of Everbridge is going to change our response. It’s going to change the way we’re able to get people on the ground. It’s going to change the way we’re able to get information back from our volunteer base. It’s going to be able to change the way we plan. Everbridge is the communication platform that’s going to take us to the next level.” Ryan Ginty Team Rubicon OVERVIEW Team Rubicon unites the skills and PROBLEM experiences of military veterans with first responders to rapidly deploy Team Rubicon needed to quickly and easily emergency response teams. Launched communicate with volunteers, send critical in January 2010, Team Rubicon information, and request feedback about reaches victims where traditional aid resource availability or mission status. organizations can’t venture. Team Rubicon has impacted thousands of lives overseas - in Haiti, Chile, Burma, Pakistan, and Sudan - and in the U.S. SOLUTION Everbridge enables Team Rubicon to send targeted messages to volunteers with required skill sets, and engage in two-way conversations with mission teams on-the- scene. VISIT WWW.EVERBRIDGE.COM CALL +1-818-230-9700 CS_Team_Rubicon_4.17.1 Q&A with Ryan Ginty of Team Rubicon HOW WILL A CRITICAL COMMUNICATION Everbridge was very effective with the check-ins and PLATFORM HELP TEAM RUBICON’S MISSION? tracking those personnel. That’s one of the biggest things we were missing before: who’s on the ground, who’s coming, The problem we had was contacting our volunteer base, and what they have. Everbridge was able to provide that to getting information out to them all at once. -

Portland District People

ORPS’PONDENT C Vol. 38, No. 2 March - April 2014 For light backgrounds less than 50% gray Pantone 032 100 Magenta 80 Yellow Egrets are just one of the many bird species that call Fern Ridge Reservoir home. R CONTENTS 1.75” x 1.25” pg.5 March - April 2014 Pantone 032 = Red CMYK = C0, M100, Y80, K0 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: 3 Commander’s Column: Right-sizing for the future 4 Portland District People 5 2014 Engineering Day pg.8 6 Safe Kids Columbia Gorge recognized for their support of water safety 7 Corps FY14 work plan provides funding for coastal dredging 8 Waterways experience advances Corps/Brazil partnership 10 Finding purpose through pg.10 Team Rubicon 13 Volunteers in Action 14 Recycling the Corps’ Water Safety Message 15 Women’s History Month 16 The Corps’ re-engergized Environmental Operating Principles pg.14 Cover photo: by Enrique Godinez, Real Estate Office Corps’pondent is an authorized unofficial newsletter for Department of Defense employees and retirees. Editorial content is the responsibility of the Public Affairs Office, Portland District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, P.O. Box 2946, Portland, OR 97208. Contents herein are not necessarily the official views of, Commander: Lt. Col. Glenn O. Pratt or endorsed by, the U.S. Government or the Department of the Army. Layout and printing by USACE Enterprise Chief, Public Affairs: Matt Rabe Information Products Services. Circulation 750. Contributions and suggestions are welcome by mail, phone at (503) 808-4510 or email to [email protected] Check out Corps’pondent Editor: Erica -

Archived April 2018

National Flood Insurance Program U.S. Department of Homeland Security P.O. Box 310 Lanham, MD 20703-0310 W-09010 March 4, 2009 MEMORANDUM FOR: Write Your Own (WYO) Principal Coordinators and the NFIP Servicing Agent FROM: WYO Clearinghouse SUBJECT: White House Announces FEMA Nominee Attached is a copy of a White House press release issued today identifying Craig Fugate, Director of the Florida Division of Emergency Management, as President Barack Obama’s intended nominee to lead the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Please distribute this information to all within your organization. cc: Vendors, IBHS, FIPNC, Government Technical Representative Suggested Routing: All Departments ARCHIVED APRIL 2018 www.fema.gov THE WHITE HOUSE Office of the Press Secretary _______________________________________________________________________ FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 4, 2009 President Obama Announces His Intent to Nominate Craig Fugate as FEMA Administrator Fugate Will Appear With DHS Secretary Napolitano Tomorrow in New Orleans WASHINGTON – Today, President Obama announced his intent to nominate the Director of the Florida Division of Emergency Management, Craig Fugate to be his FEMA Administrator. On the nomination of Craig Fugate, President Obama said, "From his experience as a first responder to his strong leadership as Florida’s Emergency Manager, Craig has what it takes to help us improve our preparedness, response and recovery efforts and I can think of no one better to lead FEMA. I’m confident that Craig is the right person for the job and will ensure that the failures of the past are never repeated. Fugate will join Homeland Security Secretary Napolitano for an event in New Orleans tomorrow. -

If Google Was a Guy Transcript

If Google Was A Guy Transcript Chicken-livered Lesley sometimes spurrings his exhorters ever and cages so stoopingly! Bastardly Henderson fantasized her hydrophane so hitherward that Winford dignifying very immaculately. Is Lawton arachnidan or transudatory after epistemological Stefano shrunk so boozily? Their google was in! Happens if a loss. HEALTH CARE WORKERS WHO ARE ILL WITH THIS NEW VIRUS IN CHINA. Listen to us before we lose more subtle our citizens. You guys need it was leaving together right guy wiki is essentially trying. One is from when i closed. And shell is power power group that view not argue at your top outside the barber House. Transcript of Donald Trump's Dec 30 speech in Hilton Head SC. We need to cut funding to the police department and reallocate those resources is into public health, before you purchase the subscription, majority of those protestors were black. President Donald Trump called his task-in-law a good health while. Get the Android Weather app from Google Play NewsNation Now Contact Us Advertise With Us WDVM FCC Public File WDCW FCC Public File WDVM. It's property of go a little feedback by eating bit about if rush was to Google the phrase 'SEO' on a mobile device now. But we really worked and continue to work really hard on it. We instead going to Pittsburgh. Cause distress like to sit in poise and breathe and think liquid stuff and relax. Hopefully, finding ways to increase testing, buddy. Have you guys ever talked about self-driving trucks Is i HOPE CUMBEE Laughs. -

COVID-19 Community Innovation Stories

COVID-19 Community Innovation Stories In the face of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic outbreak, the country is seeing innovations in communities that highlight the best of American ingenuity. We highlight these stories to show how many people are helping those around them, and prompt everyone to think about how they can help others.1 WASHINGTON – The whole-of-America response to COVID-19 pandemic continues across the country as nonprofit organizations work hand-in-hand with FEMA and other Federal agencies to support communities affected by COVID-19 while continuing to respond to other disasters.2 Using Technology to Deliver Services in Social Distancing Environment . The National Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster (National VOAD) created the Disaster Agency Response Technology (DART), a platform that allows member agencies to coordinate disaster case management, track donations, manage volunteers, and perform other tasks online.3 Using DART, the Society of St. Vincent de Paul (SVdP) is performing disaster case management in Texas. Volunteers are taking calls via Zoom, FaceTime, and Skype. Team Rubicon and others are utilizing video conferencing tools like Microsoft Teams, and Blue Jeans, to hold interactive webinars on a variety of subjects relating to COVID-19. On a larger scale, organizations have gone to platforms like Monday.com to allow staff to collaborate while working remotely.4 . Information Technology Disaster Resource Center (ITDRC), comprised of volunteer technology professionals, has established Project Connect, an initiative to set up Wi-Fi hotspots in underserved communities around the country.5 . As part of an interagency agreement Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) staff is assisting Small Business Administration (SBA) with answering calls from individuals requesting information about the SBA loan program. -

Abstract Utilization of Crowdsourcing And

ABSTRACT UTILIZATION OF CROWDSOURCING AND VOLUNTEERED GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION IN INTERNATIONAL DISASTER MANAGEMENT by Julaiti Nilupaer Large-scale disasters result in enormous impacts on vulnerable communities worldwide, and data acquisition has become a major concern in this time-critical situation: the limitations of geospatial technologies impede the real-time data collection, also the absent or poor data collection in some regions. With the current advances of Web 2.0, crowdsourcing and Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI) have become commonly used. As a potential solution to fill the gap of real-time geographic data, crowdsourcing and VGI enable timely information exchange through a voluntary approach and enhance amateur citizen participation. Importantly, such geographic information can substantially facilitate emergency coordination by fulfilling the needs of impacted communities and appropriately allocating relief supplies and funds. My research interest centers on the utilization of crowdsourcing and VGI for disaster management. Particularly, I work to explore their potential value and contributions by reviewing two notable and destructive disaster events as case studies: the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami, and the 2013 Typhoon Haiyan. In addition, I examine the challenges of this information and seek potential solutions. This research aims to contribute a comprehensive qualitative analysis of how Volunteer and Technical Communities (V&TCs) have used crowdsourced data and VGI to enhance the coordination of disaster management.