Public Monuments in Sacred Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Church Newsletter

Nativity of the Most Holy Theotokos Missionary Parish, Orange County, California CHURCH NEWSLETTER January – March 2010 Parish Center Location: 2148 Michelson Drive (Irvine Corporate Park), Irvine, CA 92612 Fr. Blasko Paraklis, Parish Priest, (949) 830-5480 Zika Tatalovic, Parish Board President, (714) 225-4409 Bishop of Nis Irinej elected as new Patriarch of Serbia In the early morning hours on January 22, 2010, His Eminence Metropolitan Amfilohije of Montenegro and the Littoral, locum tenens of the Patriarchate throne, served the Holy Hierarchal liturgy at the Cathedral church. His Eminence served with the concelebration of Bishops: Lukijan of Osijek Polje and Baranja, Jovan of Shumadia, Irinej of Australia and New Zealand, Vicar Bishop of Teodosije of Lipljan and Antonije of Moravica. After the Holy Liturgy Bishops gathered at the Patriarchate court. The session was preceded by consultations before the election procedure. At the Election assembly Bishop Lavrentije of Shabac presided, the oldest bishop in the ordination of the Serbian Orthodox Church. The Holy Assembly of Bishops has 44 members, and 34 bishops met the requirements to be nominated as the new Patriarch of Serbia. By the secret ballot bishops proposed candidates, out of which three bishops were on the shortlist, who received more than half of the votes of the members of the Election assembly. In the first round the candidate for Patriarch became the Metropolitan Amfilohije of Montenegro and the Littoral, in the second round the Bishop Irinej of Nis, and a third candidate was elected in the fourth round, and that was Bishop Irinej of Bachka. These three candidates have received more that a half votes during the four rounds of voting. -

Стаза Православља the Path of Orthodoxy the Official Publication of the Serbian Orthodox Church in North and South America

Стаза Православља THE PATH OF ORTHODOXY THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE SERBIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH IN NORTH AND SOUTH AMERICA VOLUME 47 JUNE 2012 NO. 06 Patriarch COMMUNIQUE Irinej makes 1st oF the holY aSSemblY oF biShoPS oF canonical visit the Serbian orthodox church to Canadian Held in Belgrade May 15-23, 2012 The regular meeting of the Assembly of Bishops Diocese of the Serbian Orthodox Church took place at the Serbian Patriarchate in Belgrade May 15-23, under the His Holiness Patriarch Irinej of presidency of His Holiness Serbian Patriarch Irinej. Serbia made his first canonical visit to the Participating in the Assembly were all the diocesan Diocese of Canada April 20-25, 2012. His hierarchs of the Serbian Orthodox Church, with the Grace Bishop Georgije of Canada greeted exception of His Beatitude Archbishop of Ochrid His Holiness at the Diocesan Center, the Holy Transfiguration Monastery in and Metropolitan of Skopje Jovan who is unjustly Milton, Ontario, following a Doxology imprisoned in the Skoplje prison of Idrizovo and His at the Holy Three Hierarchs Chapel. Grace Bishop Chrysostom of Bihac and Petrovac. Wishing him a warm welcome, he asked The Assembly began its work with the joint the Patriarch to bestow the blessings of On Bright Friday, His Holiness Patriarch Irinej addresses the faithful at serving of the hierarchical Divine Liturgy in the Holy St. Sava upon the clergy, monastics and Holy Transfiguration Monastery in Milton-Toronto, Canada Archangel Michael Cathedral in Belgrade, led by faithful people of the Diocese of Canada. Serbian Patriarch Irinej, and served the Invocation During his visit Patriarch Irinej took part in the other jurisdictions joined His Holiness in the liturgical of the Holy Spirit, the Spirit of truth and wisdom, in celebration of the 25th anniversary of the Diocesan periodical celebration where a record congregation of the faithful was Whom the Church lives and always works, especially “Istocnik”, on Bright Friday, at Holy Transfiguration present to receive a blessing from their spiritual father. -

Destruction and Preservation of Cultural Heritage in Former Yugoslavia, Part II

Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe Volume 29 Issue 1 Article 1 2-2009 Erasing the Past: Destruction and Preservation of Cultural Heritage in Former Yugoslavia, Part II Igor Ordev Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Ordev, Igor (2009) "Erasing the Past: Destruction and Preservation of Cultural Heritage in Former Yugoslavia, Part II," Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe: Vol. 29 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree/vol29/iss1/1 This Article, Exploration, or Report is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ERASING THE PAST: DESTRUCTION AND PRESERVATION OF CULTURAL HERITAGE IN FORMER YUGOSLAVIA Part II (Continuation from the Previous Issue) By Igor Ordev Igor Ordev received the MA in Southeast European Studies from the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece. Previously he worked on projects like the World Conference on Dialogue Among Religions and Civilizations held in Ohrid in 2007. He lives in Skopje, Republic of Macedonia. III. THE CASE OF KOSOVO AND METOHIA Just as everyone could sense that the end of the horrifying conflict of the early 1990s was coming to an end, another one was heating up in the Yugoslav kitchen. Kosovo is located in the southern part of former Yugoslavia, in an area that had been characterized by hostility and hatred practically ‘since the beginning of time.’ The reason for such mixed negative feelings came due to the confusion about who should have the final say in the governing of the Kosovo principality. -

Biography Curriculum Vitae Vuk F

Biography Curriculum Vitae Vuk F. Dautović Address: Department of Art History Faculty of Philosophy University of Belgrade Čika Ljubina 18-20 1100 Belgrade room 479 Phone number: +381 11 3206246 Cell phone: +381 63 70 98 308 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Skype: vukdau Born on August 10th, 1977 in Belgrade, Serbia. Scientific-Research Infrastructure of the Republic of Serbia number: RIS 130940 Current position: Ph.D. Candidate and Research Assistant at the Department of Art History, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Belgrade. Education: 2010 to present, Ph.D. Candidate, Department of Art History, Faculty of Philosophy, Belgrade University, at Art History and Visual Culture of the Early modern period seminary. Ph.D. Thesis: “Art and Liturgical Ritual: Ecclesiastical objects in Serbian visual culture of the 19th century” Dissertation advisor: Prof. dr Nenad Makuljević. 2008-2009 Master of Arts in Art History, Faculty of Philosophy, Belgrade University. Thesis: “Artistic modeling and symbolic decoration of chalices in 19th century Serbia”, Thesis supervisor: Prof. dr Nenad Makuljević. 1999-2008 Bachelor of Arts in Art History, Faculty of Philosophy, Belgrade University. 1997-1999 Academy for conservation and arts of Serbian Orthodox Church, Belgrade Academic service: 2011 to present, assisting Prof. dr Saša Brajović in teaching Art History and visual culture of the Early modern period in Western Europe, at the Department of Art History, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Belgrade. (Teaching courses: Art in Early Modern Europe 1, Introduction to the art and visual culture of Early modern and Modern period, Art and visual culture of the Mediterranean world) Projects, Memberships: 2011 to present, member of the research project: “Representation of Identity in Art and Verbal- Visual Culture of the Early modern period”. -

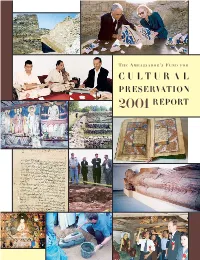

2001 Annual Report

02-0608_CulturalPreservation 5/30/02 8:46 AM Page FC1 T HE A MBASSADOR’ S F UND FOR CULTURAL PRESERVATION 2001 REPORT 02-0608_CulturalPreservation 5/30/02 8:46 AM Page FC2 Albania, Algeria, Angola, Armenia, Bangladesh, Belarus, Belize, Benin, Bhutan, Bolivia, Botswana, Brazil, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cambodia, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, China, Colombia, Comoros, Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Fiji, Gabon, Gambia, Georgia, Ghana, Guatemala, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Jamaica, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Kyrgyz Republic, Laos, Latvia, Lebanon, Lesotho, Macedonia, Madagascar, Malawi, Malaysia, Maldives, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Moldova, Mongolia, Morocco, Mozambique, Myanmar, Namibia, Nepal, Nicaragua, Niger, Nigeria, Oman, Pakistan, Panama, Papua New Guinea, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Romania, Russian Federation, Rwanda, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Samoa (Western), São Tomé and Principe, Saudi Arabia, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Solomon Islands, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Suriname, Swaziland, Syria, Tajikistan, Tanzania, Thailand, Togo, Tunisia, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Uganda, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Vanuatu, Venezuela, Vietnam, Yemen, Zambia, Zimbabwe 02-0608_CulturalPreservation 5/30/02 8:46 AM Page 1 Albania, Algeria, Angola, Armenia, Bangladesh, Belarus, Belize, Benin, Bhutan, Bolivia, Botswana, Brazil, Bulgaria, Burkina -

Evocations of Byzantium in Zenitist Avant-Garde Architecture Jelena Bogdanović Iowa State University, [email protected]

Architecture Publications Architecture 9-2016 Evocations of Byzantium in Zenitist Avant-Garde Architecture Jelena Bogdanović Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/arch_pubs Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, and the Byzantine and Modern Greek Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ arch_pubs/78. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Architecture at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Architecture Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Evocations of Byzantium in Zenitist Avant-Garde Architecture Abstract The yB zantine legacy in modern architecture can be divided between a historicist, neo-Byzantine architectural style and an active investigation of the potentials of the Byzantine for a modern, explicitly nontraditional, architecture. References to Byzantium in avantgarde Eastern European architecture of the 1920s employed a modernist interpretation of the Byzantine concept of space that evoked a mode of “medieval” experience and creative practice rather than direct historical quotation. The va ant-garde movement of Zenitism, a prominent visionary avant-garde movement in the Balkans, provides a case study in the ways immaterial aspects of Byzantine architecture infiltrated modernism and moved it beyond an academic, reiterative formalism. By examining the visionary architectural design for the Zeniteum, the Zenitist center, in this article, I aim to identify how references to Byzantium were integrated in early twentieth-century Serbian avant-garde architecture and to address broader questions about interwar modernism. -

The Herpetological Collection of the Institute for Biological Research “Siniša Stanković”, University of Belgrade

Bulletin of the Natural History Museum, 2017, 10: 57-104. Received 21 Jun 2017; Accepted 17 Sep 2017. doi:10.5937/bnhmb1710057D UDC: 069.51:597.6/598.1(497.11); 57/59:005.71(497.11) Original scientific paper THE HERPETOLOGICAL COLLECTION OF THE INSTITUTE FOR BIOLOGICAL RESEARCH “SINIŠA STANKOVIĆ”, UNIVERSITY OF BELGRADE GEORG DŽUKIĆ1, LJILJANA TOMOVIĆ2*, MARKO ANĐELKOVIĆ1, ALEKSANDAR UROŠEVIĆ1, SONJA NIKOLIĆ2, MILOŠ KALEZIĆ1 1 University of Belgrade, Institute for Biological Research “Siniša Stanković”, Bulevar Despota Stefana 142, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia 2 University of Belgrade, Faculty of Biology, Institute of Zoology, Studentski trg 16, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia, e-mail: [email protected] Key words: Reptiles, collection INTRODUCTION The history of the Herpetological collection of the Institute for Biological Research “Siniša Stanković” University of Belgrade is 80 years long. The collection was initially formed from private donations and by collecting new samples in the field. Also, the herpetological collection of the Institute of Zoology, Faculty of Natural Sciences University of Belgrade was added to it. This early collection consisted of samples from ex-Yugoslavia. Unfortunately, large parts of the initial collection suffered an immeasurable damage during the Second World War: most of the 58 DŽUKIĆ, G. ET AL.: HERPETOLOGICAL COLLECTION – INSTITUTE “S. STANKOVIĆ” documentation and a large number of specimens were destroyed. During the professional career of Professor Milutin Radovanović (1900–1968), the collection was expanded. His seminal work has laid foundations of herpetology in the entire region, together with acquisition and organizing of the material in the collection. His contribution prior to 1941 included samples from islands of the Adriatic Sea (present-day Croatia). -

Glory to God for All Things! Repose of St

Ambo ST. THEODOSIUS ORTHODOX CATHEDRAL 733 Starkweather Ave. Cleveland, Ohio MARCH 16, 2008 1ST SUNDAY OF GREAT LENT Mailing: SUNDAY OF ORTHODOXY 733 Starkweather Avenue Cleveland, Ohio 44113 T 216 741.1310 F 216 623 1092 Glory to God for All Things! www.sttheodosius.org Repose of St. Nicholas of Zhicha • Archpriest John Zdinak Dean • Archpriest Pavel Soucek Attached/Retired • Subdeacon Theodore Lentz Sacristan • Reader Julius Kovach - Ecclesiarch & Choirmaster Divine Services Eve Sundays & Feast Days 5:00 PM Confessions 6:00 PM Great Vespers Sundays and Feast Days 8:40 AM 3rd and 6th Hour 9:00 AM Divine Liturgy St. Theodosius Orthodox Cathedral Ambo - Page 1 Saint Nicholas of Zhicha, "the Serbian Chrysostom," was born in Lelich in western Serbia on January 4, 1881 (December 23, 1880 O.S.). His parents were Dragomir and Katherine Velimirovich, who lived on a farm where they raised a large family. His pious mother was a major influence on his spiritual develop- ment, teaching him by word and especially by example. As a small child, Nicholas often walked three miles to the Chelije Monastery with his mother to attend services there. Sickly as a child, Nicholas was not physically strong as an adult. He failed his physical requirements when he applied to the military academy, but his excellent academic qualifications allowed him to enter the St Sava Seminary in Belgrade, even before he finished preparatory school. After graduating from the seminary in 1905, he earned doctoral degrees from the University of Berne in 1908, and from King's College, Oxford in 1909. When he returned home, he fell ill with dysentery. -

January 24, 2021- Christ's Trial Before Caiaphus, St. Paisios and More

Iconography Adult Spiritual Enrichment January 24, 2021 CLASS 14 ST PAISIOS (JUNE 29 / JULY 12) On 25 July 1924, Arsenios Eznepidis was born in Pharasa (Çamlıca), Cappadocia, shortly before the population exchange between Greece and Turkey. Arsenios' name was given to him by St. Arsenios the Cappadocian, who baptised him, naming the child for himself and foretelling Arsenios' monastic future. After the exchange, the Eznepidis family settled in Konitsa, Epirus. Arsenios grew up there, and after intermediate public school, he learned carpentry. Also, as a child he had great love for Christ and the Panagia, and a great longing to become a monk. He would often leave for the forest in order to study and pray in silence. He took delight in the lives of the Saints, the contests of whom he struggled to imitate with zeal immeasurable and exactness astounding, cultivating in the process humility and love. During the civil war in Greece, Arsenios served as a radio operator (1945-1949). In combat operations, he was distinguished for his bravery, self-sacrifice, and moral righteousness. In 1950, having completed his service, he went to Mount Athos to become a monk: first to Father Kyril, the future abbot of Koutloumousiou monastery, and then to Esphigmenou Monastery (although he was not supportive of their later opposition to the Ecumenical Patriarchate). Arsenios, having been a novice for four years, was tonsured a Rassophore monk on 27 March 1954, and was given the name Averkios. Soon after, Father Averkios went to the idiorrhythmic brotherhood of Philotheou monastery, where his uncle was a monk. -

Abstracts 2Nd RICONTRANS Workshop ICONS in MOTION

9-11 SEPTEMBER 2021 Abstracts 2nd RICONTRANS Workshop ICONS IN MOTION: RUSSIAN RELIGIOUS ART, VISUAL CULTURE AND COLLECTIVE IDENTITIES IN THE BALKANS AND THE EAST MEDITERRANEAN LOCATION: UNIVERSITY OF BELGRADE | FACULTY OF PHILOSOPHY The RICONTRANS project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 818791) Visual Culture, Piety and Propaganda: Transfer and Reception of Russian Religious Art in the Balkans and the Eastern Mediterranean (16th – early 20th century) https://ricontrans-project.eu/ The Russian religious artefacts (icons and ecclesiastical furnishings), held in museums, church or monastery collections in the Balkans and the Eastern Mediterranean, constitute a body of valuable monuments hitherto largely neglected by historians and historians of art. These objects acquire various interrelated religious, ideological, political and aes- thetic meanings, value, and uses. Their transfer and reception constitutes a significant component of the wider process of transformation of the artistic language and visual culture in the region and its transition from medieval to modern idioms. It is at the same time a process reflecting the changing cultural and political relations between Russia and the Orthodox communities in the Ottoman Empire and its successor states in the Balkans over a long period of time (16th- early 20th century). In this dynamic transfer, piety, propaganda and visual culture appear intertwined in historically unexplored and theoretically provoking ways. RICONTRANS explores the thousands of Russian Icons and other religious art objects, brought from Russia to the Balkans from the 16th until the 20th century, preserved in monasteries, churches, and museum collections in the region. -

SERBIA: Very Slow Official Implementation of Restitution Law

FORUM 18 NEWS SERVICE, Oslo, Norway http://www.forum18.org/ The right to believe, to worship and witness The right to change one's belief or religion The right to join together and express one's belief This article was published by F18News on: 12 March 2007 SERBIA: Very slow official implementation of Restitution Law By Drasko Djenovic, Forum 18 News Service <http://www.forum18.org> Serbia's Restitution Law is being implemented only very slowly, Forum 18 News Service has found. Even the "traditional" religious communities, who have automatic legal status, are having problems in making claims, including the Serbia Orthodox Church which suffered more confiscations than other communities. The Jewish community had much property confiscated during the Second World War, but the Law covers only post-1945 confiscations. Slovak Lutheran Church Bishop Samuel Vrbovsky told Forum 18 he is "not too optimistic" about the restitution process. "My only hope is that because the Serbian Orthodox Church has significant property to be returned, we smaller communities will also get our property back as well." The Islamic community has "a long list of confiscated property," but is finding it difficult to exercise its legal rights. Both "traditional" and "non-traditional" communities are finding it difficult to assemble the documentation required to prove ownership. As the state has been extremely slow in implementing the Restitution Law, it is not yet possible to judge the fairness of the process. Implementation of Serbia's Law on the Restitution of Property to Churches and Religious Communities - which came into force in late 2006 - has been extremely slow, Forum 18 News Service has found. -

Руско-Српске Културне Везе У Огледалу Музике Russian-Serbian Cultural Relations Reflected in Music

28 I/2020 Руско-српске културне везе у огледалу музике Russian-Serbian Cultural Relations Reflected in Music Гост уредник В С П Guest Editor V S P Музикологија Часопис Музиколошког института САНУ Musicology Jоurnal of the Institute of Musicology SASA ~ 28 (I /2020) ~ ГЛАВНИ И ОДГОВОРНИ УРЕДНИК / EDITOR-IN-CHIЕF Александар Васић / Aleksandar Vasić РЕДАКЦИЈА / ЕDITORIAL BOARD Ивана Весић, Јелена Јовановић, Данка Лајић Михајловић, Ивана Медић, Биљана Милановић, Весна Пено, Катарина Томашевић / Ivana Vesić, Jelena Jovanović, Danka Lajić Mihajlović, Ivana Medić, Biljana Milanović, Vesna Peno, Katarina Tomašević СЕКРЕТАР РЕДАКЦИЈЕ / ЕDITORIAL ASSISTANT Милош Браловић / Miloš Bralović МЕЂУНАРОДНИ УРЕЂИВАЧКИ САВЕТ / INTERNATIONAL EDITORIAL COUNCIL Светислав Божић (САНУ), Џим Семсон (Лондон), Алберт ван дер Схоут (Амстердам), Јармила Габријелова (Праг), Разија Султанова (Лондон), Денис Колинс (Квинсленд), Сванибор Петан (Љубљана), Здравко Блажековић (Њујорк), Дејв Вилсон (Велингтон), Данијела Ш. Берд (Кардиф) / Svetislav Božić (SASA), Jim Samson (London), Albert van der Schoot (Amsterdam), Jarmila Gabrijelova (Prague), Razia Sultanova (London), Denis Collins (Queensland), Svanibor Pettan (Ljubljana), Zdravko Blažeković (New York), Dave Wilson (Wellington), Danijela Š. Beard (Cardiff) Музикологија је рецензирани научни часопис у издању Музиколошког института САНУ. Посвећен је проучавању музике као естетског, културног, историјског и друштвеног феномена и примарно усмерен на музиколошка и етномузиколошка истраживања. Редакција такође прихвата интердисциплинарне радове у чијем је фокусу музика. Часопис излази два пута годишње. Упутства за ауторе се могу преузети овде: http://www.doiserbia.nb.rs/journal.aspx?issn=1450- 9814&pg=instructionsforauthors Musicology is a peer-reviewed journal published by the Institute of Musicology SASA (Belgrade). It is dedicated to the research of music as an aesthetical, cultural, historical and social phenomenon and primarily focused on musicological and ethnomusicological research.