Full Report (Download PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Railway Network

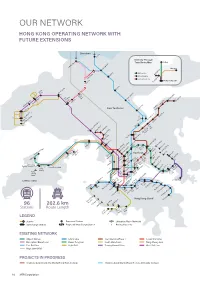

Railway Network Railways play a vital role in serving the transport needs of COVID-19 pandemic. By end 2020, the AEL carries about Hong Kong. They account for about 39 per cent of domestic 8 400 passenger trips per day. public transport by end 2020. Light Rail: Light Rail is a local transportation network Existing Network: The existing railway network in Hong which started operation in 1988 to meet the transport needs of Kong has a total route length of about 263 kilometres. The the residents in the northwest New Territories. It now has a Legislative Council passed in June 2007 the Rail Merger route length of about 36 km with 68 stops. By end 2020, it Ordinance which provides the legal framework for the carries an average of about 305 600 passenger trips every post-merger corporation to operate both the Mass Transit day. It has four interchange stations in Yuen Long, Tin Shui Railway (MTR) system and Kowloon-Canton Railway (KCR) Wai, Siu Hong and Tuen Mun to facilitate passenger system. The post-merger Corporation, i.e. the MTR interchange between the Light Rail and West Rail Line Corporation Limited (MTRCL) has been granted a 50-year networks. franchise to operate the MTR and KCR systems with effect from December 2, 2007. Other fixed track systems include the Hong Kong Section of Guangzhou-Shenzhen-Hong Tramway and the Peak Tram. Kong Express Rail Link (XRL): The Hong Kong section of the XRL, commissioned in September 2018, is a 26-km long MTR: MTR is a heavily patronized railway network underground rail corridor connecting Hong Kong with the consisting of 10 heavy rail lines, Airport Express and the Hong national high-speed rail network. -

The Chief Executive's 2020 Policy Address

The Chief Executive’s 2020 Policy Address Striving Ahead with Renewed Perseverance Contents Paragraph I. Foreword: Striving Ahead 1–3 II. Full Support of the Central Government 4–8 III. Upholding “One Country, Two Systems” 9–29 Staying True to Our Original Aspiration 9–10 Improving the Implementation of “One Country, Two Systems” 11–20 The Chief Executive’s Mission 11–13 Hong Kong National Security Law 14–17 National Flag, National Emblem and National Anthem 18 Oath-taking by Public Officers 19–20 Safeguarding the Rule of Law 21–24 Electoral Arrangements 25 Public Finance 26 Public Sector Reform 27–29 IV. Navigating through the Epidemic 30–35 Staying Vigilant in the Prolonged Fight against the Epidemic 30 Together, We Fight the Virus 31 Support of the Central Government 32 Adopting a Multi-pronged Approach 33–34 Sparing No Effort in Achieving “Zero Infection” 35 Paragraph V. New Impetus to the Economy 36–82 Economic Outlook 36 Development Strategy 37 The Mainland as Our Hinterland 38–40 Consolidating Hong Kong’s Status as an International Financial Centre 41–46 Maintaining Financial Stability and Striving for Development 41–42 Deepening Mutual Access between the Mainland and Hong Kong Financial Markets 43 Promoting Real Estate Investment Trusts in Hong Kong 44 Further Promoting the Development of Private Equity Funds 45 Family Office Business 46 Consolidating Hong Kong’s Status as an International Aviation Hub 47–49 Three-Runway System Development 47 Hong Kong-Zhuhai Airport Co-operation 48 Airport City 49 Developing Hong Kong into -

Transport Infrastructure and Traffic Review

Transport Infrastructure and Traffic Review Planning Department October 2016 Hong Kong 2030+ 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 PREFACE ........................................................... 1 5 POSSIBLE TRAFFIC AND TRANSPORT 2 CHALLENGES ................................................... 2 ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE STRATEGIC Changing Demographic Profile .............................................2 GROWTH AREAS ............................................. 27 Unbalanced Spatial Distribution of Population and Synopsis of Strategic Growth Areas ................................. 27 Employment ........................................................................3 Strategic Traffic and Transport Directions ........................ 30 Increasing Growth in Private Vehicles .................................6 Possible Traffic and Transport Arrangements ................. 32 Increasing Cross-boundary Travel with Pearl River Delta Region .......................................................................7 3 FUTURE TRANSPORT NETWORK ................... 9 Railways as Backbone ...........................................................9 Future Highway Network at a Glance ................................11 Connecting with Neighbouring Areas in the Region ........12 Transport System Performance ..........................................15 4 STRATEGIC DEVELOPMENT DIRECTIONS FROM TRAFFIC AND TRANSPORT PERSPECTIVE ................................................. 19 Transport and Land Use Optimisation ...............................19 Railways Continue to be -

Annex List of Development Bureau's Initiatives in the Policy Address Supplement a List of Development Bureau's Ongoing

Annex List of Development Bureau’s Initiatives in the Policy Address Supplement A list of Development Bureau’s ongoing and new initiatives stipulated in the Policy Address Supplement is appended below. They are mainly under the Chapters of “Upholding and Improving the ‘One Country, Two Systems’ Practice”, “Together, We Fight the Virus”, “Housing and Land Supply”, “Unlimited Business Opportunities”, “Liveable City” and “Caring Society”. Upholding and Improving the “One Country, Two Systems” Practice Progress Made Upgraded the Project Cost Management Office (PCMO) in April 2019 to the Project Strategy and Governance Office (PSGO) to implement various measures to optimise the performance of infrastructure projects. In the past four years, the PCMO/PSGO scrutinised more than 280 public works projects of a total estimated cost of $520 billion and achieved cost savings of $70 billion through optimising project designs. Maintained oversight of the implementation of the new High Court and District Court projects by the central steering committee established under the Judiciary. The statutory rezoning procedures for the latter’s development site is expected to be completed within 2020. Completed the second round consultation with the industry on the extent of adopting IMS as a listing requirement of Government's approved public works contractors by 30 September 2020. Continued to invest in infrastructure to meet Hong Kong’s needs and create jobs. From 2017-18 to 2020-21, the average capital works expenditure per year amounted to $75.5 billion. Together, We Fight the Virus New Initiatives Complete the construction of Penny’s Bay Quarantine Centre - 1 - Phases III and IV in December 2020 for provision of another 2 000 quarantine units. -

Hong Kong Government's Policy Address 2020

Hong Kong Government’s Policy Address 2020 Key Takeaways primarily relevant to the Real Estate and Infrastructure sector November 25, 2020 Summary Authors/Presenters This year’s Policy Address was delivered today (25th November 2020) amidst the backdrop of a changing and dynamic environment. The Chief Executive (“CE”) has set out a variety of key initiatives to address the city’s land Andrew MacGeoch and housing supply, infrastructure, the environment, Co-Author collaboration with the Greater Bay Area (“GBA”), and HK’s Partner and Regional Practice Group Leader - Real Estate ongoing role as an international financial center. We set Asia out a list of key takeaways below highlighting primarily Hong Kong [email protected] those aspects involving real estate and infrastructure. OPENING This year’s Policy Address was delivered today (25th November 2020) amidst the backdrop of a changing and dynamic environment. The Chief Executive (“CE”) has set out a variety of key initiatives to address the city’s land and housing supply, infrastructure, the environment, collaboration with the Greater Bay Area (“GBA”), and HK’s ongoing role as an international financial center. We set Page 1 of 11 out a list of key takeaways below highlighting primarily those aspects involving real estate and infrastructure. LAND SUPPLY Increasing land supply is a top priority of the Government. Glenn Haley At present, the Government has identified new land supply Co-Author with a total area of 90 hectares along the Northern Link, Partner Hong Kong including the San Tin / Lok Ma Chau Development Node. [email protected] Further initiatives to support the increase of land supply include: Development of Siu Ho Wan Depot Site. -

Transport Department the Asiaworld-Expo

Transport Every day, about 8.93 million passenger journeys are Public Light Buses (PLBs) are minibuses with not more made on a public transport system which includes railways, than 19 seats. Their number is fixed at a maximum of 4 350 trams, buses, minibuses, taxis and ferries in 2020. vehicles. Some PLBs are used for scheduled services (green There are about 373 licensed vehicles for every kilometre minibuses) and others for non-scheduled services (red of road, and the topography makes it increasingly difficult to minibuses). provide additional road capacity in the heavily built-up areas. Red minibuses are free to operate anywhere, except where special prohibitions apply, without fixed routes or fares. By end Buses and Minibuses: By end December 2020, the Kowloon December 2020, there are 1 009 red minibuses. Motor Bus Company (1933) Limited (KMB) operates 359 bus Green minibuses operate on fixed routes and frequencies routes in Kowloon and the New Territories and 65 cross- at fixed prices. By end December 2020, there are 67 main harbour routes. Fares range from $3.2 to $13.4 for urban green minibus routes on Hong Kong Island, 82 in Kowloon and routes, from $2 to $46.5 for the New Territories routes and 211 in the New Territories, employing a total of 3 341 vehicles. from $8.8 to $39.9 for the cross-harbour routes. Red minibuses carry about 183 300 passengers a day, while With a fleet of 3 997 licensed air-conditioned buses, mostly green minibuses carry about 1 116 200 passengers daily Note double-deckers, KMB is one of the largest road passenger 2. -

Paper on Replacement of Traffic Control and Surveillance System

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(4)619/20-21(06) Ref. : CB4/PL/TP Panel on Transport Meeting on 19 March 2021 Updated background brief on replacement of traffic control and surveillance systems in government tunnels Purpose This paper provides updated information on the replacement of the traffic control and surveillance systems ("TCSSs") in government tunnels and the Tsing Ma Control Area ("TMCA"). It also summarizes the major discussions by Legislative Council ("LegCo") Members on financial proposals on the replacement of TCSSs in the past. Background Traffic control and surveillance systems 2. Since early 1980's, all road tunnels and TMCA have been equipped with comprehensive traffic control and surveillance facilities including closed circuit television ("CCTV") cameras, automatic incident detectors, lane control signals ("LCS"), variable speed limit signs ("VSLS") and variable message signs, etc. for efficient and effective traffic and incident management. 3. Based on the information available on the website of the Transport Department ("TD"),1 TCSSs have been expanded in recent years to include Shenzhen Western Corridor, Tolo Highway, Tsing Sha Control Area, Tuen Mun Road, Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge, Central Wanchai Bypass, Heung Yuen Wai Highway and Tuen Mun-Chek Lap Kok Link. New TCSSs are now being or will be implemented as part of the highway projects including the widening of Tai Po Road (Sha Tin Section), widening of Fanling Highway, Tseung Kwan O – Lam Tin Tunnel, Cross Bay Link (Tseung Kwan O), Central 1 The relevant website of TD: https://www.td.gov.hk/en/transport_in_hong_kong/its/its_achievements/traffic_control_and _surveillance_systems/index.html [Accessed March 2021]. -

Procedure and Practice Adopted by the Board in Conducting Its Business So That Consistency Can Be Ensured

PART I - INTRODUCTION Preamble 1.1 The conduct of the Town Planning Board (the Board or TPB) is subject to the provisions of the Town Planning Ordinance (the Ordinance) (Cap. 131) and the general principles of administrative law that it must act fairly and reasonably. This document incorporates the procedure and practice adopted by the Board in conducting its business so that consistency can be ensured. This document is subject to revision as and when considered necessary. Establishment and Functions of the Board 1.2 The Board is a statutory body established under section 2 of the Ordinance. 1.3 The Board’s main functions are laid down in section 3 of the Ordinance, i.e. to undertake the systematic preparation of plans for the layout of such areas of Hong Kong (i.e. Outline Zoning Plans and Development Permission Area Plans) as well as for the types of buildings suitable for erection therein with a view to the promotion of the health, safety, convenience and general welfare of the community. The Board also considers applications for amendment of plan under section 12A, for planning permission under section 16 and amendment to planning permission under section 16A of the Ordinance and conducts, under section 17, reviews on its decisions on section 16 and section 16A applications. 1.4 Furthermore, under section 25 of the Urban Renewal Authority (URA) Ordinance, Cap. 563, the URA may submit any plan prepared under subsection (3)(a) of the URA Ordinance to the Board for consideration. Upon the submission of a plan so prepared by the URA, the Board may deem the plan as suitable for publication, with or without amendments, or may refuse to deem the plan as being suitable for publication. -

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 24

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 24 March 2021 4357 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 24 March 2021 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE ANDREW LEUNG KWAN-YUEN, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JEFFREY LAM KIN-FUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG TING-KWONG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE STARRY LEE WAI-KING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAK-KAN, B.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KIN-POR, G.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PRISCILLA LEUNG MEI-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-KIN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS REGINA IP LAU SUK-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE PAUL TSE WAI-CHUN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE MICHAEL TIEN PUK-SUN, B.B.S., J.P. 4358 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 24 March 2021 THE HONOURABLE STEVEN HO CHUN-YIN, B.B.S. THE HONOURABLE FRANKIE YICK CHI-MING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE YIU SI-WING, B.B.S. THE HONOURABLE MA FUNG-KWOK, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAN-PAN, B.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG CHE-CHEUNG, S.B.S., M.H., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALICE MAK MEI-KUEN, B.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE KWOK WAI-KEUNG, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHRISTOPHER CHEUNG WAH-FUNG, S.B.S., J.P. -

For Discussion

Annex 1 Proposed Job Description Chief Town Planner/District Urban Renewal Forum Rank : Chief Town Planner (D1) Responsible to : Assistant Director/Metro Major Duties and Responsibilities – 1. To perform the role of Secretary to the advisory platform of District Urban Renewal Forum (DURF) in the pilot areas. 2. To supervise and manage the provision of secretariat services and professional advice to enable effective operation and functioning of DURFs. To closely engage the major stakeholders in the process and attend meetings with various committees, professional groups, trade-related bodies, and non-government organisations (NGOs) as directed by DURFs as well as other liaison meetings / discussion forums / workshops / briefings to gauge the views of the stakeholders / organisations / concerned groups. 3. To help commission and manage the consultants in undertaking consultancy studies proposed by DURFs, formulate Urban Regeneration Plans for the areas, and to translate them, where appropriate, into detailed Action Area Plans for implementation. To keep in view other urban renewal initiatives by the government sector and the non-government sector in the pilot districts with a view to formulating an integrated urban renewal blueprint at the district level. 4. To help commission and manage the public engagement exercises, and present the findings to DURFs and, where appropriate, to present those findings to the relevant committees, professional groups, trade-related bodies, NGOs and any other bodies to facilitate the implementation of proposals. 5. To provide briefings for policy bureaux, departments, public utility agencies, the mass media and the general public on DURF related matters in the pilot districts. - 2 - 6. To review and report the effectiveness of the pilot DURFs with a view to recommending the way forward of this pilot framework within the intended timeframe. -

Audit Commission Hong Kong 25 October 2010

CHAPTER 3 Hong Kong Observatory Hong Kong Observatory Audit Commission Hong Kong 25 October 2010 This audit review was carried out under a set of guidelines tabled in the Provisional Legislative Council by the Chairman of the Public Accounts Committee on 11 February 1998. The guidelines were agreed between the Public Accounts Committee and the Director of Audit and accepted by the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Report No. 55 of the Director of Audit contains 11 Chapters which are available on our website at http://www.aud.gov.hk. Audit Commission 26th floor, Immigration Tower 7 Gloucester Road Wan Chai Hong Kong Tel : (852) 2829 4210 Fax : (852) 2824 2087 E-mail : [email protected] HONG KONG OBSERVATORY Contents Paragraph PART 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background 1.2 Financial provision and staffing 1.3 – 1.4 Audit review 1.5 Acknowledgement 1.6 PART 2: AUTOMATIC WEATHER STATIONS 2.1 Automatic weather station network 2.2 Removal of automatic weather 2.3 stations and weather element sensors Audit observations and recommendation 2.4 – 2.5 Response from the Administration 2.6 Maintenance of meteorological 2.7 equipment at automatic weather stations Audit observations and recommendations 2.8 – 2.11 Response from the Administration 2.12 Maintenance of non-meteorological equipment 2.13 by the Electrical and Mechanical Services Department Audit observations and recommendations 2.14 – 2.17 Response from the Administration 2.18 – 2.19 Site selection for new automatic weather stations 2.20 Audit observations and recommendations -

Our Network Hong Kong Operating Network with Future Extensions

OUR NETWORK HONG KONG OPERATING NETWORK WITH FUTURE EXTENSIONS Shenzhen Lo Wu Intercity Through Train Route Map Beijing hau i C Lok Ma Shanghai Sheung Shu g Beijing Line Guangzhou Fanlin Shanghai Line Kwu Tung Guangdong Line n HONG KONG SAR Dongguan San Ti Tai Wo Long Yuen Long t Ping 48 41 47 Ngau a am Tam i Sh i K Mei a On Shan a Tai Po Marke 36 K Sheungd 33 M u u ui Wa W Roa Au Tau Tin Sh 49 Heng On y ui Hung Shui Ki g ng 50 New Territories Tai Sh Universit Han Siu Ho 30 39 n n 27 35 Shek Mu 29 Tuen Mu cecourse* e South Ra o Tan Area 16 F 31 City On Tuen Mun n 28 a n u Sha Ti Sh n Ti 38 Wai Tsuen Wan West 45 Tsuen05 Wa Tai Wo Ha Che Kung 40 Temple Kwai Hing 07 i 37 Tai Wa Hin Keng 06 l Kwai Fong o n 18 Mei Fo k n g Yi Diamond Hil Kowloon Choi Wa Tsin Tong n i King Wong 25 Shun Ti La Lai Chi Ko Lok Fu d Tai Si Choi Cheung Sha Wan Hung Sau Mau Ping ylan n ay e Sham Shui Po ei Kowloon ak u AsiaWorld-Expo B 46 ShekM T oo Po Tat y Disn Resort m Po Lam Na Kip Kai k 24 Kowl y Sunn eong g Hang Ha Prince n Ba Ch o Sungong 01 53 Airport M Mong W Edward ok ok East 20 K K Toi ong 04 To T Ho Kwa Ngau Tau Ko Cable Car n 23 Olympic Yau Mai Man Wan 44 n a Kwun Ti Ngong Ping 360 19 52 42 n Te Ti 26 Tung Chung East am O 21 L Tung Austi Yau Tong Tseung Chung on Whampo Kwan Tung o n Jordan Tiu g Kowl loo Tsima Hung 51 Ken Chung w Sh Hom Leng West Hong Kong Tsui 32 t Tsim Tsui West Ko Eas 34 22 ha Fortress10 Hill Hong r S ay LOHAS Park ition ew 09 Lantau Island ai Ying Pun Kong b S Tama xhi aus North h 17 11 n E C y o y Centre Ba Nort int 12 16 Po 02 Tai