The Colorful, Complicated, Slightly Schizophrenic, History of Early Computer Art at Bell Labs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Online Software Piracy of the Last Millennium.Sxw

Online Software Piracy of the Last Millennium By Ben Garrett aka Ipggi Ever since there has been the ability to store data on a personal computer and commercial software for sale, there has been the existence of pirating. Pirating, cracking and even pirate scenes go all the way back to the late seventies, and maybe even earlier. By the early eighties some machines (such as the BBC Macro in Europe) where so riddled with pirates that the programming companies gave up. They discontinued producing and porting software for the affected computers because there was simply no money to be made. This article has been written with only the PC scene in mind. Table of Contents 1. The IBM PC Scene Beginnings Page 1 2. Bulletin Board Systems And Couriers 2 3. The Death of the Bulletin Board System and the Rise of the Internet 4 4. Software Suppliers 5 5. Text Files 5 6. Scene Art 6 7. The Emergence of Europe 6 8. The Death of the Floppy Disk 6 9. Evolution to the ISO scene 7 10.Bibliography 8 1. The IBM PC Scene Beginnings With the large amount of 8-bit computers around during the early eighties, otherwise known as the Golden Age. And then with the subsequence scenes that followed, most people will agree that the Commodore 64 scene was the greatest at the time. But the Commodore 64 1 wasn't the first computer system to have an organised international pirate scene. It was probably the Apple II users in the very late seventies 2 that can be credited with creating the first remnant of a pirate scene that would be familiar in todays internet warez world. -

Press Release E.A.T.—Experiments in Art and Technology

Press Release E.A.T.—Experiments in Art and Technology July 25–November 1, 2015 Mönchsberg [3] & [4] The Museum der Moderne Salzburg presents an international premiere: a Presse comprehensive survey of the groundbreaking projects of E.A.T.—Experiments Mönchsberg 32 in Art and Technology, an evolving association of artists and technologists 5020 Salzburg who wrote history in the 1960s and 1970s with projects between New York and Austria Osaka. The show is on view on the Mönchsberg. T +43 662 842220-601 F +43 662 842220-700 Salzburg, July 24, 2015. The Museum der Moderne Salzburg mounts the first-ever comprehensive retrospective of the activities of Experiments in Art and Technology [email protected] www.museumdermoderne.at (E.A.T.), a unique association of engineers and artists who wrote history in the 1960s and 1970s. Artists like Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008) and Robert Whitman (b. 1935) teamed up with Billy Klüver (1927–2004), a visionary technologist at Bell Telephone Laboratories, and his colleague Fred Waldhauer (1927–1993) to launch a groundbreaking initiative that would realize works of art in an unprecedented collaborative effort. The Museum der Moderne Salzburg dedicates two levels of its temporary exhibition galleries on the Mönchsberg with over 16,000 sq ft of floor space to this seminal venture fusing art and technology; around two hundred works of art and projects ranging from kinetic objects, installations, and performances to films, videos, and photographs as well as drawings and prints exemplify the most important stages of E.A.T.’s evolution. “In the past smaller exhibitions have highlighted the best-known events in E.A.T.’s history, but a comprehensive panorama of the group’s activities that reveals the full range and diversity of E.A.T.’s output has long been overdue. -

The Creativity of Artificial Intelligence in Art

The Creativity of Artificial Intelligence in Art Mingyong Cheng Duke University October 19th, 2020 Abstract New technologies, especially in the field of artificial intelligence, are dynamic in transforming the creative space. AI-enabled programs are rapidly contributing to areas like architecture, music, arts, science, and so on. The recent Christie's auction on the Portrait of Edmond has transformed the contemporary perception of A.I. art, giving rise to questions such as the creativity of this art. This research paper acknowledges the persistent problem, "Can A.I. art be considered as creative?" In this light, the study draws on the various applications of A.I., varied attitudes on A.I. art, and the processes of generating A.I. art to establish an argument that A.I. is capable of achieving artistic creativity. 1 Table of Contents Chapter One ..................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 4 2.1 Overview ................................................................................................................................ 7 2.2 Defining Artificial Intelligence .............................................................................................. 8 2.3 Application of AI in Various Fields .................................................................................... 10 2.3.1 Music ............................................................................................................................ -

Siggraph 1986

ACM SIGGRAPH 86 ART SHOW ART SHOW CHAIR CONFERENCE CO-CHAIRS Patric Prince Ellen Gore California State University, Los Angeles ISSCO Raymond L. Elliott Los Alamos National Laboratory ART SHOW COMMITTEE Maxine D. Brown Maxine Brown Associates SPACE COMMITTEE Donna J. Cox Darcy Gerbarg University of Illinois School of Visual Arts Paul Allen Newell Barbara Mones Abel Image Research Montgomery College Sylvie Rueff John. C. Olvera Jet Propulsion Laboratory North Texas State University Gary Walker Jet Propulsion Laboratory PROFESSIONAL ASSISTANCE Gayle Westrate Independent Deborah Sokolove Colman PHOTOGRAPHS Monochrome Color ESSAYS Herbert W. Franke John Whitney Ken Knowlton Frank Dietrich Patric Prince LISTS OF WORKS Tho-dimensional/Three-dimensional Works Installations Animations FRONT COVER CREDIT ISBN 800-24 7-7004 © 1986 ACM SIGGRAPH © 1985 David Em, Zotz I 1986 ACM SIGGRAPH ART SHOW: A RETROSPECTIVE Since the mid-Sixties, computer art has been seen in museums and galleries world-wide, with several recent major exhibitions. However, the pieces shown were usually the artists' newer works. It is appropriate and pertinent at this year's exhibition to show computer-aided art in the context of that which went before. The 1986 art show traces the development of computer art over the past twenty-five years through the work of artists who have been involved with it from its inception. The 1986 art show is the fifth exhibition of fine art that ACM SIGGRAPH has sponsored in conjunction with its annual SIGGRAPH conference. Patric D. Prince ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank Louise Ledeen for her support and advice, the Art Show committee for their billions and billions of donated hours, and the nucleus of dedicated volunteers who have worked diligently to produce this art show. -

Media Art Net | Generative Tools | Computer Art

Media Art Net | Generative Tools | Computer Art Note: If you see this text you use a browser which does not support usual Web-standards. Therefore the design of Media Art Net will not display correctly. Contents are nevertheless provided. For greatest possible comfort and full functionality you should use one of the recommended browsers. Editorial Generative Art Software Art Game Art Computer Art Themes Generative Tools Computer Art What is Computer Art? An attempt towards an answer and examples of interpretation Matthias Weiß «No instrument plays itself or writes its own music.» Per Cederqvist[1] «That which is programmable must also be computable.» Frieder Nake[2] «It is understood that the artistic goal of THE SOFTWARE is to express conceptual ideas as software. It is also understood that THE SOFTWARE is partially automated, and its output is a result of its process. Despite the process being an integral part of THE SOFTWARE, this does not imply nor grant the status of artwork on the output of THE SOFTWARE. This is the sole responsibility of YOU (the USER).» Signwave Auto-Illustrator LICENSE AGREEMENT (for Version 1.2), § 7.3 A. Towards an Ahistorical Assessment of the Computer Art Scene The history of reflection on the artistic use of computer software and hardware did not begin with transmediale.01. For artists who employ computer programming, however, that event, as the first international festival of its kind—the origin of which,like the origin of virtually all of the efforts in art history involving new procedures in technologybased artistic strategies and production methods lies in video technology—provided an impetus for new, more extensive explorations of software programmes, and found its most recent, and broadest platform to date at the Ars Electronica 2003. -

MFA Thesis.Pdf

VIRTUAL ART; USING COMPUTER ARTISTRY TO EVOLVE PAINTING AND SCULPTURE BY PAA KWAME BAAH A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTERS OF FINE ART (MFA) PAINTING AND SCULPTURE Faculty of Fine Art, College of Art and Social Sciences ©April 2008, Department of Painting and Sculpture i DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is an account on my project topic, solely done under the guidance of my supervisors, Mr. G. Y. Annum and Mr. Lee Nukpe, both from the Faculty of Fine Art, College of Art and Social Sciences, KNUST. It has not been presented partially or wholly to any other university of institution in the award of any degree. PAA KWAME BAAH ---------------------------- ------------------------ PG 7024004 Signature Date Candidate MR G. Y. ANNUM --------------------------- ------------------------- Supervisor Signature Date MR LEE NUKPE --------------------------- ------------------------- Supervisor Signature Date MR G. Y. ANNUM --------------------------- ------------------------- Head of Department Signature Date ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I am most grateful to God above all things for bringing me this far. I am indebted to Mr. G. Y. Annum and Mr. Lee Nukpe, for their guidance and direction. Also to Dr. Prof. R. T. Ackam, kari kacha sei-du, and all the lecturers of the Painting and Sculpture Department, I extend a warm gratitude and special thanks for all your encouragement and tolerance. Finally to my well-wishing colleagues and friends, especially James Nii Adjei Ala, and Makafui, I say thank you for your immense help, support and favour given me during the time of need. -

Creating Continuity Between Computer Art History and Contemporary Art

CAT 2010 London Conference ~ 3rd February Bruce Wands _____________________________________________________________________ CREATING CONTINUITY BETWEEN COMPUTER ART HISTORY AND CONTEMPORARY ART Bruce Wands Chair, MFA Computer Art Director of Computer Education Director, New York Digital Salon School of Visual Arts 209 East 23 Street New York, NY 10010 USA [email protected] www.mfaca.sva.edu www.nydigitalsalon.org Computer art was started by a small group of pioneering artists who had the vision to see what digital tools and technology could bring to the creative process. The technology at the time was primitive, compared to what we have today, and these artists faced resistance from the traditional art establishment. Several organizations, such as the New York Digital Salon, were started to promote digital creativity through exhibitions, publications and websites. This paper will explore how to create continuity between computer art history and a new generation of artists that does not see making art with computers as unusual and views it as contemporary art. INTRODUCTION The origins of computer art trace back over fifty years as artists began to experiment and create artwork with new technologies. Even before computers were invented, photography, radio, film and television opened up new creative territories. Many people point to the photographs of abstract images taken of an oscilloscope screen that Ben Laposky called Oscillons as some of the first electronic art images, which foreshadowed the development of computer art. While the system he used was essentially analog, the way in which the images were created was through mathematics and electronic circuitry. Another artist working at that time was Herbert Franke, and as the author of Computer Graphics – Computer Art, originally published in 1971, and followed in 1985 by an expanded second edition, he began to document the history of computer art and the artists who were involved. -

Table of Contents

Donna J. Cox Vita Curriculum June 2013 Table of Contents 1 Table of Contents 2 Abbreviated Vita 4 Authored Publications 7 Invited Shows / Festivals / Exhibitions 12 Juried Shows / Festivals / Exhibitions 13 Installations / Performances / Exhibits 19 Invited Keynotes / Plenary Presentations 22 Panels and Other Presentations 26 Citations/Reviews of Creative Work 32 Published Images / Animations (see also Appendix) 34 Television / Radio Appearances 35 Other Professional Activities / Service 38 Grants/Commissions 39 Grants/Commissions (current) Appendix: Circulation Statistics 40 Hubble 3D IMAX film 41 Dynamic Earth digital fulldome show 44 Black Holes digital fulldome show 48 Additional Published Images / Animations 1 Professor Donna J. Cox, MFA, PhD Michael Aiken Chair Cox is a professor in the School of Art and Design, Director Illinois eDream Institute and Director Advanced Visualization Lab, National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) University of Illinois 1/09 … Present Director, eDream Institute http://edream.ncsa.illinois.edu/ 8/06 … Present Director, Advanced Visualization Laboratory http://avl.ncsa.uiuc.edu 12/08 Computing and Communications, PhD, University of Plymouth, UK 2/02 … 8/06 Director, Visualization and Experimental Technologies, NCSA 8/00 … 2/02 Special Projects, Research Artist/Scientist, NCSA 1/99 ... 8/00 Chair External Initiatives, School of Art & Design 8/97 … 8/00 Director, Virtual Director Group, NCSA 8/92 ... Present Professor, School of Art & Design 8/90 ... 8/99 Associate Director for Technologies, School of Art & Design 3/92 ... 8/93 Co-Director, Scientific Communications and Media Systems, NCSA 8/90 ... 8/92 Associate Professor, School of Art & Design 8/89 ... 3/92 Associate Director for Education, NCSA 1/89 .. -

Mosaic Portraits: New Methods and Strategies Ken Knowlton

Likely Preface to a Possible Book Mosaic Portraits: New Methods and Strategies Ken Knowlton If you don't know where you're going, you will surely end up somewhere else. Yogi Berra To be sure of hitting the target, shoot first, and call whatever you hit the target. Ashleigh Brilliant Basic research is what I'm doing when I don't know what I am doing. Werner von Braun One never goes so far as when one doesn't know where one is going. Goethe Through today's lens - near-future and pragmatic - it was a place of misty legend: that brick and mortar fortress on a hill in the Northeast Kingdom of New Jersey. Quiet and apparently innocuous. But stealthy, to those who read its press releases as warnings of upheaval down the road. To most folks, its announcements - about atoms, plasmas, phonons, and such figments of science - were of little relevance to their composures or bottom lines. Bell Telephone Laboratories, as my colleagues and I experienced it during the 1960s and 1970s, was a beehive of scientific and technological scurrying. Practitioners within, tethered on long leashes if at all, were earnestly seeking enigmatic solutions to arcane puzzles. What happened there would have baffled millions of telephone subscribers who, knowingly or not, agreeably or not, supported the quiet circus. For people who believe in science, and who still believe in technology, it was the epitome of free exploration into how the world did, or could, work. For those concerned with tangible results, the verdict, albeit delayed, is indisputable: fiber optics, the transistor, Echo and Telstar, radio astronomy including confirmation of the Big Bang. -

Chapter 4: a HISTORY of COMPUTER ANIMATION 3/20/92 2

Chapter 4 : A HISTORY OF COMPUTER ANIMATION 3/20/92 1 A Chronology Of Animation History Computer Animation Technology prepared by Judson Rosebush C 1989-1990 This is document CHRON4.DOC Chapter 4: A HISTORY OF COMPUTER ANIMATION 3/20/92 2 360,000,000 BC - first known tetrapods (4 legged terrestrial vertebrates) appear. 1,500,000 BC - Kindling wood employed in building fire. 1,000,000 BC - Humans migrate out of Africa and use stone tools in Jordan . 350,000 BC - Alternate date for Homo erectus uses fire. [decide which you want Judson .] 250,000 BC - Brain capacity of neanderthal man exceeds 1000 cubic centimeters. 120,000 BC - Man builds shelters with roof supported by wooden beams. 50,000 BC - Body paint employed as decoration and camaflage . 43,000 BC - Homo sapiens matures; brain capacity exceeds 1500 cc's and spoken language is developed. 32,000 BC - Neanderthal hunters employ superimposed positions to depict the action of a running boar. First recorded drawings with temporal component . [but isn't the date too early?] 25,000 BC - Clothing begins to be tailored. Czechoslovaks make kiln fired clay figures of people and animals . 15,000 BC - Cave painters at Lascaux, France superimpose stars over the sketch of a bull creating the oldest record of a star constellation. Because most modern (Arabic) star names describe the part of the constellation where the star is located it is theorized that constellations were named before the individual stars . 8600 BC - Brick houses are built in Jerico, Palestine. 8450 BC - Accounting and counting systems: Persians use clay tokens as bills of lading for shipments. -

Heart Beats Dust: the Conservation of an Interactive Installation from 1968 and an Introduction to E.A.T (Experiments in Art and Technology)

Presented at the Electronic Media Group Session, AIC 35th Annual Meeting May 15–20, 2009, Los Angeles, CA. HEART BEATS DUST: THE CONSERVATION OF AN INTERACTIVE INSTALLATION FROM 1968 AND AN INTRODUCTION TO E.A.T (EXPERIMENTS IN ART AND TECHNOLOGY) CHRISTINE FROHNERT ABSTRACT This paper begins with a short historic overview of installations including electric and electronic components in works of art from the United States. The roots of this work go back to the 1960s, when artists and engineers started to collaborate and create installations, eventually forming the pioneering group E.A.T. (Experi- ments in Art and Technology). Today, these early technology-based artworks made by E.A.T.—mainly in the 1960s—are relatively little known, primarily as a result of the complexities of preserving, displaying, and properly maintaining them. While technologically advanced at the time when they were created, some components have become outmoded or obsolete and are hard to preserve (Davidson 1997, 290). Keeping these artworks “alive” without changing their technological and functional integrity is possible, to some degree, but there is a fine line between preserva- tion, conservation, and re-creation, which will be addressed and discussed in more detail. COLLABORATION BETWEEN ARTISTS AND ENGINEERS IN THE UNITED STATES In 1960, Billy Klüver (1927–2004), a Swedish-American engineer at Bell Tele- phone Laboratories and the Swiss artist Jean Tinguely (1925–1991) started their collaboration in building the self-destroying machine Homage To New York (1960) in the garden of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City (figs. 1, 2). -

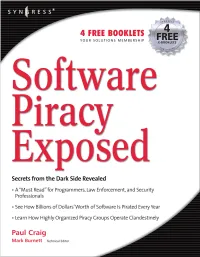

Software Piracy Exposed.Pdf

323_Sof_Pir_FM.qxd 8/30/05 2:19 PM Page i Register for Free Membership to [email protected] Over the last few years, Syngress has published many best-selling and critically acclaimed books, including Tom Shinder’s Configuring ISA Server 2004, Brian Caswell and Jay Beale’s Snort 2.1 Intrusion Detection, and Angela Orebaugh and Gilbert Ramirez’s Ethereal Packet Sniffing. One of the reasons for the success of these books has been our unique [email protected] program. Through this site, we’ve been able to provide readers a real time extension to the printed book. As a registered owner of this book, you will qualify for free access to our members-only [email protected] program. Once you have registered, you will enjoy several benefits, including: ■ Four downloadable e-booklets on topics related to the book. Each booklet is approximately 20-30 pages in Adobe PDF format. They have been selected by our editors from other best-selling Syngress books as providing topic coverage that is directly related to the coverage in this book. ■ A comprehensive FAQ page that consolidates all of the key points of this book into an easy-to-search web page, pro- viding you with the concise, easy-to-access data you need to perform your job. ■ A “From the Author” Forum that allows the authors of this book to post timely updates and links to related sites, or additional topic coverage that may have been requested by readers. Just visit us at www.syngress.com/solutions and follow the simple registration process.