No. 12 April 1968 SOME ASPECTS of COMPOSING By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11 Triple Loyd

TTHHEE PPUUZZZZLLIINNGG SSIIDDEE OOFF CCHHEESSSS Jeff Coakley TRIPLE LOYDS: BLACK PIECES number 11 September 22, 2012 The “triple loyd” is a puzzle that appears every few weeks on The Puzzling Side of Chess. It is named after Sam Loyd, the American chess composer who published the prototype in 1866. In this column, we feature positions that include black pieces. A triple loyd is three puzzles in one. In each part, your task is to place the black king on the board.to achieve a certain goal. Triple Loyd 07 w________w áKdwdwdwd] àdwdwdwdw] ßwdwdw$wd] ÞdwdRdwdw] Ýwdwdwdwd] Üdwdwdwdw] Ûwdwdpdwd] Údwdwdwdw] wÁÂÃÄÅÆÇÈw Place the black king on the board so that: A. Black is in checkmate. B. Black is in stalemate. C. White has a mate in 1. For triple loyds 1-6 and additional information on Sam Loyd, see columns 1 and 5 in the archives. As you probably noticed from the first puzzle, finding the stalemate (part B) can be easy if Black has any mobile pieces. The black king must be placed to take away their moves. Triple Loyd 08 w________w áwdwdBdwd] àdwdRdwdw] ßwdwdwdwd] Þdwdwdwdw] Ýwdw0Ndwd] ÜdwdPhwdw] ÛwdwGwdwd] Údwdw$wdK] wÁÂÃÄÅÆÇÈw Place the black king on the board so that: A. Black is in checkmate. B. Black is in stalemate. C. White has a mate in 1. The next triple loyd sets a record of sorts. It contains thirty-one pieces. Only the black king is missing. Triple Loyd 09 w________w árhbdwdwH] àgpdpdw0w] ßqdp!w0B0] Þ0ndw0PdN] ÝPdw4Pdwd] ÜdRdPdwdP] Ûw)PdwGPd] ÚdwdwIwdR] wÁÂÃÄÅÆÇÈw Place the black king on the board so that: A. -

Weltenfern a Commented Selection of Some of My Works Containing 149 Originals

Weltenfern A commented selection of some of my works containing 149 originals by Siegfried Hornecker Dedicated to the memory of Dan Meinking and Milan Velimirovi ć who both encouraged me to write a book! Weltenfern : German for other-worldly , literally distant from the world , describing a person’s attitude In the opinion of the author the perfect state of mind to compose chess problems. - 1 - Index 1 – Weltenfern 2 – Index 3 – Legal Information 4 – Preface 6 – 20 ideas and themes 6 – Chapter One: A first walk in the park 8 – Chapter Two: Schachstrategie 9 – Chapter Three: An anticipated study 11 – Chapter Four: Sleepless nights, or how pain was turned into beauty 13 – Chapter Five: Knightmares 15 – Chapter Six: Saavedra 17 – Chapter Seven: Volpert, Zatulovskaya and an incredible pawn endgame 21 – Chapter Eight: My home is my castle, but I can’t castle 27 – Intermezzo: Orthodox problems 31 – Chapter Nine: Cooperation 35 – Chapter Ten: Flourish, Knightingale 38 – Chapter Eleven: Endgames 42 – Chapter Twelve: MatPlus 53 – Chapter 13: Problem Paradise and NONA 56 – Chapter 14: Knight Rush 62 – Chapter 15: An idea of symmetry and an Indian mystery 67 – Information: Logic and purity of aim (economy of aim) 72 – Chapter 16: Make the piece go away 77 – Chapter 17: Failure of the attack and the romantic chess as we knew it 82 – Chapter 18: Positional draw (what is it, anyway?) 86 – Chapter 19: Battle for the promotion 91 – Chapter 20: Book Ends 93 – Dessert: Heterodox problems 97 – Appendix: The simple things in life 148 – Epilogue 149 – Thanks 150 – Author index 152 – Bibliography 154 – License - 2 - Legal Information Partial reprint only with permission. -

The Puzzling Side of Chess

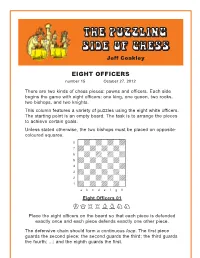

TTHHEE PPUUZZZZLLIINNGG SSIIDDEE OOFF CCHHEESSSS Jeff Coakley EIGHT OFFICERS number 15 October 27, 2012 There are two kinds of chess pieces: pawns and officers. Each side begins the game with eight officers: one king, one queen, two rooks, two bishops, and two knights. This column features a variety of puzzles using the eight white officers. The starting point is an empty board. The task is to arrange the pieces to achieve certain goals. Unless stated otherwise, the two bishops must be placed on opposite- coloured squares. w________w áwdwdwdwd] àdwdwdwdw] ßwdwdwdwd] Þdwdwdwdw] Ýwdwdwdwd] Üdwdwdwdw] Ûwdwdwdwd] Údwdwdwdw] wÁÂÃÄÅÆÇÈw Eight Officers 01 KQRRBBNN Place the eight officers on the board so that each piece is defended exactly once and each piece defends exactly one other piece. The defensive chain should form a continuous loop. The first piece guards the second piece; the second guards the third; the third guards the fourth; ...; and the eighth guards the first. Eight Officers 02 KQRRBBNN Place the eight officers on the board so that they have the most possible moves. Eight Officers 03a KQRRBBNN Place the eight officers on the board so that they attack the most squares. A piece does not attack the square it stands on. To count as an “attacked square”, the occupied square must be attacked by another piece. Here’s a hint. The solution is less than 64 squares. Eight Officers 03b KQRRBBNN Place the eight officers on the board so that all empty squares are attacked and none of the pieces attack each other. In other words, all occupied squares are unattacked. -

Developing Chess Talent

Karel van Delft and Merijn van Delft Developing Chess Talent KVDC © 2010 Karel van Delft, Merijn van Delft First Dutch edition 2008 First English edition 2010 ISBN 978-90-79760-02-2 'Developing Chess Talent' is a translation of the Dutch book 'Schaaktalent ontwikkelen', a publication by KVDC KVDC is situated in Apeldoorn, The Netherlands, and can be reached via www.kvdc.nl Cover photo: Training session Youth Meets Masters by grandmaster Artur Yusupov. Photo Fred Lucas: www.fredlucas.eu Translation: Peter Boel Layout: Henk Vinkes Printing: Wbhrmann Print Service, Zutphen CONTENTS Foreword by Artur Yusupov Introduction A - COACHING Al Top-class sport Al.1 Educational value 17 Al.2 Time investment 17 Al.3 Performance ability 18 A1.4 Talent 18 Al. 5 Motivation 18 A2 Social environment A2.1 Psychology 19 A2.2 Personal development 20 A2.3 Coach 20 A2.4 Role of parents 21 A3 Techniques A3.1 Goal setting 24 A3.2 Training programme 25 A3.3 Chess diary 27 A3.4 Analysis questionnaire 27 A3.5 A cunning plan! 28 A3.6 Experiments 29 A3.7 Insights through games 30 A3.8 Rules of thumb and mnemonics 31 A4 Skills A4.1 Self-management 31 A4.2 Mental training 33 A4.3 Physical factors 34 A4.4 Chess thinking 35 A4.5 Creativity 36 A4.6 Concentration 39 A4.7 Flow 40 A4.8 Tension 40 A4.9 Time management 41 A4.10 Objectivity 44 A4.11 Psychological tricks 44 A4.12 Development process 45 A4.13 Avoiding blunders 46 A4.14 Non-verbal behaviour 46 3 AS Miscellaneous A5.1 Chess as a subject in primary school 47 A5.2 Youth with adults 48 A5.3 Women's chess 48 A5.4 Biographies -

The Reviled Art Stuart Rachels

The Reviled Art Stuart Rachels “If chess is an art, it is hardly treated as such in the United States. Imagine what it would be like if music were as little known or appreciated. Suppose no self-respecting university would offer credit courses in music, and the National Endowment for the Arts refused to pay for any of it. A few enthusiasts might compose sonatas, and study and admire one another’s efforts, but they would largely be ignored. Once in a while a Mozart might capture the public imagination, and like Bobby Fischer get written about in Newsweek. But the general attitude would be that, while this playing with sound might be clever, and a great passion for those who care about it, still in the end it signifies nothing very important.” —James Rachels1 Bragging and Whining When I was 11, I became the youngest chess master in American history. It was great fun. My picture was put on the cover of Chess Life; I appeared on Shelby Lyman’s nationally syndicated chess show; complete strangers asked me if I was a genius; I got compared to my idol, Bobby Fischer (who was not a master until he was 13); and I generally enjoyed the head-swelling experience of being treated like a king, as a kid among adults. When I wasn’t getting bullied at school, I felt special. And the fact that I was from Alabama, oozing a slow Southern drawl, must have increased my 2 mystique, since many northeastern players assumed that I lived on a farm, and who plays chess out there? In my teens, I had some wonderful experiences. -

Chess Composer Werner 2

Studies with Stephenson I was delighted recently to receive another 1... Êg2 2. Îxf2+ Êh1 3 Í any#, or new book by German chess composer Werner 2... Êg3/ Êxh3 3 Îb3#. Keym. It is written in English and entitled Anything but Average , with the subtitle Now, for you to solve, is a selfmate by one ‘Chess Classics and Off-beat Problems’. of the best contemporary composers in the The book starts with some classic games genre, Andrei Selivanov of Russia. In a and combinations, but soon moves into the selfmate White is to play and force a reluctant world of chess composition, covering endgame Black to mate him. In this case the mate has studies, directmates, helpmates, selfmates, to happen on or before Black’s fifth move. and retroanalysis. Werner has made a careful selection from many sources and I was happy to meet again many old friends, but also Andrei Selivanov delighted to encounter some new ones. would happen if it were Black to move. Here 1st/2nd Prize, In the world of chess composition, 1... Êg2 2 Îxf2+ Êh1 3 Í any#; 2... Êg3/ Êxh3 Uralski Problemist, 2000 separate from the struggle that is the game, 3 Îb3# is clear enough, but after 1...f1 Ë! many remarkable things can happen and you there is no mate in a further two moves as will find a lot of them in this book. Among the 2 Ía4? is refuted by 2... Ëxb1 3 Íc6+ Ëe4+! . most remarkable are those that can occur in So, how to provide for this good defence? problems involving retroanalysis. -

FIDE Olympic Tourney 2018 – Studies (Draw) 18 Chess Composers from 12 Countries Participated in the Tournament.Overall 22 Studies Were Submited

FIDE Olympic Tourney 2018 – Studies (Draw) 18 chess composers from 12 countries participated in the tournament.Overall 22 studies were submited. It was particularly hard for me to judge studies that contained mutual zugwzang. 1st prize - Sergei Didukh (Ukraine) Interresting thematic try and two-way logic elements from both sides. 2nd prize – Martin Minski (Germanu) German chess composer has once again crafted immaculete study with masterful design. 3rd prize - Steffen Slumstrup Nielsen (Norway) Using famous chess combinations composer developed study into one with nuance and subtlety. 1st prize – Sergei Didukh (Ukraine) Draw 1.Sc1!! White plan. Logical try 1.Rg8? Qxh7 2.Rxg7+ Qxg7+ 3.Kxg7 h4 4.Sxd4 Kg4! 5.f3+ Kg5 6.Se6+ Kf5 7.Sd4+ Ke5 8.Sc6+ Kd5 9.Se7+ Kc4! Black plan. (9...Kc5? 10.Sg6 h3 11.Sxf4 h2 12.Sd3+!) 10.d3+ (10.Sf5 h3 11.Sxd6+ Kd3!–+) 10...Kc5! 11.Sg6 (11.Sg8 f5!) 11...h3 12.Sxf4 h2–+ and 13.Nd3+ is impossible. 1...Qc2 2.Rg8 Qxh7 (2...Qc8+ 3.Ke7!=) 3.Rxg7+ Qxg7+ 4.Kxg7 d3! 4...h4 5.Se2 h3 (5...Kg4 6.Sg1=) 6.Sg1! h2 7.Sf3+. 5.Sb3! Switchback. 5.Sxd3? h4 6.f3 h3 7.Sf2 h2 8.a4 Kh4 9.a5 Kg3 10.Sh1+ Kg2 11.a6 Kxh1 12.a7 Kg2 13.a8Q h1Q–+ 5...h4 6.Sd4 Kg4! 7.f3+ Kg5! Switchback. 7...Kg3 8.Sf5+ Kxf3 9.Sxh4+ Ke2 10.a4=. 8.Se6+ Kf5 9.Sd4+ Ke5 10.Sc6+ Kd5 11.Se7+ Kc4 11...Kc5 12.Sg6 h3 13.Sxf4 h2 14.Sxd3+ Kd4 15.Sf2; 11...Ke6 12.Sg6 h3 13.Sxf4+. -

Chess Endgame Table Base Records

International Robotics & Automation Journal Editorial Open Access Chess endgame table base records Introduction Volume 3 Issue 5 - 2019 Before the construction of seven–piece bases the longest known win in the endings was a win in 243 moves (before conversion) in Yakov Konoval, Karsten Müller the ending “a rook and a knight against two knights”, found by Lewis Designation Computer Chess, University Orenburg State Stiller in 1991. Later it has been established that the record to mate University, Russia in this class of the endings makes 262 moves. It has appeared that in the seven–piece endings there are longer wins. A win in 290 moves Correspondence: Karsten Müller, Designation Computer in the ending “two rooks and a knight against two rooks” became the Chess, University Orenburg State University, Russia, Tel first of them. Further variety of records has been found still. In May 7–3532–777362, Email 2006 the position with a win in 517 moves has been found in the Received: November 20, 2017 | Published: December 06, ending a queen and a knight against a rook, a bishop and a knight. 2017 Black to move and white wins in 517 moves (Figure 1). In general in many pawn less endings more than 50 moves before conversion are necessary for a win, and it was already known and for a number of six–pieced and even the five–pieced endings, even such ending, as “a queen and a rook against a queen”. Even in pawn full endings there are many positions where a huge number of moves are needed for win. -

Keverel-Books-Autumn2019.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS To view a particular category within the catalogue please click on the headings below. To return to this Table of Contents click on the red text at the bottom of each section 1. Antiquarian 2. Reference; Encyclopaedias, & History 3. Tournaments 4. Game collections of specific players 5. Game Collections - General 6. Endings 7. Problems, Studies & “Puzzles” 8. Instructional 9. Magazines & Yearbooks 10. Chess-based literature 1. Antiquarian Bird, H. E. Chess History & Reminiscences London 1893 138pp Has sections on chess history, blindfold chess and a few game scores. Original brown cloth with bright gilt titles. LN 236 VG+ £85.00 Bird, H. E. Chess Practice being a condensed and simplified record of the actual openings in the finest games played up to the present time, including the whole of the beautiful specimens contained in Chess Masterpieces, London 1st comprising those of Anderson, Bird, Blackburne, Boden, Buckle, ed. 1882 Cochrane, Kolisch, Labourdonnais, Lowenthal, Macdonnell, Morphy, Staunton, Steinitz Zuckertort, and 35 others. 96pp Original dark cloth. LN 1822 Front binding a little tender o/w VG £75.00 Bird, H. E. Chess Practice London 1892 96pp LN 1823 A 2nd printing a decade after the first, but with a much more colourful red cloth cover with Art Nouveau titles and £75.00 chessboard. Insc “Edward Metcalfe” VG . Bird, H. E. The Chess Openings considered Critically & Practically. 1st ed. 1877 London Includes interesting long lists of subscribers in UK & US, including Sam Loyd who composed a special letter B problem for the book. 248pp Original blue cloth boards with gilt title on spine. -

The Application of Chess Theory PERGAMON RUSSIAN CHESS SERIES

The Application of ChessT eory PERGAMON RUSSIAN CHESS SERIES The Application of Chess Theory PERGAMON RUSSIAN CHESS SERIES General Editor: Kenneth P. Neat Executive Editor: Martin J. Richardson AVERBAKH, Y. Chess Endings: Essential Knowledge Comprehensive Chess Endings Volume 1 : Bishop Endings & Knight Endings BOTVINNIK, M. M. Achieving the Aim Anatoly Karpov: His Road to the World Championship Half a Century of Chess Selected Games 1967-1970 BRONSTEIN, D. & SMOLYAN, Y. Chess in the Eighties ESTRIN, Y. & PANOV, V. N. Comprehensive Chess Openings GELLER, Y. P. 100 Selected Games KARPOV, A. & GIK, Y. Chess Kaleidoscope KARPOV, A. & ROSHAL, A. Anatoly Karpov: Chess is My Life LIVSHITZ, A. Test Your Chess IQ, Books 1 & 2 NEISHTADT, Y. Catastrophe in the Opening Paul Keres Chess Master Class POLUGAYEVSKY, L. Grandmaster Preparation SMYSLOV, V. 125 Selected Games SUETIN, A. S. I Modem Chess Opening Theory ' Three Steps to Chess Mastery TAL, M., CHEPTZHNY, V. & ROSHAL, A. Montreal1979: Tournament of Stars The Application of Chess Theory By Y. P. GELLER InternationalGrandmaster Translated by KENNETH P. NEAT PERGAMON PRESS OXFORD • NEW YORK • TORONTO • SYDNEY • PARIS • FRANKFURT U.K. Pergamon Press Ltd., Headington Hill Hall, Oxford OX3 OBW, England U.S.A. Pergamon Press Inc., Maxwell House, Fairview Park, Elmsford, New York 10523, U.S.A. CANADA Pergamon Press Canada Ltd., Suite 104, ISO Consumers Rd., Willowdale, Ontario M2J IP9, Canada AUSTRALIA Pergamon Press (Aust.) Pty. Ltd., P.O. Box 544, Potts Point, N.S.W. 2011, Australia FRANCE Pergamon Press SARL, 24 rue desEcoles, 75240 Paris, Cedex 05, France FEDERAL REPUBUC Pergamon Press GmbH, Hammerweg 6, OF GERMANY D-6242 Kronberg-Taunus, Federal Republic of Germany English translation copyright© 1984 K.P. -

Against the Torrent of Awards in Chess Composition

Against the torrent of awards in chess composition "The chessmen are like printing types bringing thought into form; and although these thoughts leave a visual impression on the chessboard, their beauty is abstract like a poem." (Marcel Duchamp) Introduction Chess paired itself in a variety of relationships with several arts because of its high cultural heritage. Thus we find it, for example, as a musical theme, in literature with Stefan Zweig and his "Schachnovelle", and in the paintings of many major artists. One of them is Marcel Duchamp (28. 7. 1887 - 2. 10. 1968), a pioneer of Dadaism and Surrealism, who entirely devoted himself to the game of chess after his painter career, and as such participated in five chess olympiads as a member of the French national team. He created this oil painting: But chess doesn't need to be paired with other arts to be deemed as part of art - chess can become an art on its own. This is because chess composition - the composition of chess problems and endgame studies - usually is seen as an art, because it's not chained to the terms of a chess game and thus allows its creators the opportunity to display chess ideas in crystal-clear form without any unnecessary ballast. Some games may be described as a piece of art, too. In chess compositions, however, the struggle for the victory, which marks a game of chess, largely gives way to the presentation of art. Some time ago the well-known chess player and chess composer Yochanan Afek reassured me: "I will just say that for me a chess study is first Marcel Duchamp: and foremost a creation of art and as such it should contain a theme or leitmotif The game of chess, 1910 (preferably original) and a process of paradoxical moves leading to some surprising climex, some highlight. -

Read Book One Hundred Chess Problems

ONE HUNDRED CHESS PROBLEMS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Arthur Cyril Pearson | 148 pages | 25 Aug 2010 | Nabu Press | 9781177696555 | English | Charleston SC, United States One Hundred Chess Problems PDF Book When he died, he had the third largest chess book collection in the world. Quite basic stuff with long explanations, good for a slow start. Thursby, Seventy-Five Chess Problems Fold-outs, if any, are not part of the book. Translations exist in German, French, View basket. He was editor of StrateGems , the publication of the Society of U. Yves Cheylan Kallitexniko skaki Greek. Corners, spine ends bumped and rubbed with some fraying to spine ends, light rippling to cover else about very good copy. First Edition. Fairy chess problems. His best work is in the form of helpmates and fairy problems. He also classified chess players into five distinct classes. Schultz, Schackuppgifter Category Games. A chess problem, also called a chess composition, is a puzzle set by somebody using chess pieces on a chess board, that presents the solver with a particular task to be achieved. Dejaschacchi, Rook ending Problems. Published by Universal Publications, London. Three copies of his manuscript was discovered in , the earliest dating from Some months ago I made the error of posting published checkmate puzzles to share with others in the community. Marjan Kovacevic You will be mesmerized by the incredible sacrifices and unlikely moves that result in checkmate. The perfect gift. United Kingdom. We expect that you will understand our compulsion in these books. We appreciate your support of the preservation process, and thank you for being an important part of keeping this knowledge alive and relevant.