Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The German North Sea Ports' Absorption Into Imperial Germany, 1866–1914

From Unification to Integration: The German North Sea Ports' absorption into Imperial Germany, 1866–1914 Henning Kuhlmann Submitted for the award of Master of Philosophy in History Cardiff University 2016 Summary This thesis concentrates on the economic integration of three principal German North Sea ports – Emden, Bremen and Hamburg – into the Bismarckian nation- state. Prior to the outbreak of the First World War, Emden, Hamburg and Bremen handled a major share of the German Empire’s total overseas trade. However, at the time of the foundation of the Kaiserreich, the cities’ roles within the Empire and the new German nation-state were not yet fully defined. Initially, Hamburg and Bremen insisted upon their traditional role as independent city-states and remained outside the Empire’s customs union. Emden, meanwhile, had welcomed outright annexation by Prussia in 1866. After centuries of economic stagnation, the city had great difficulties competing with Hamburg and Bremen and was hoping for Prussian support. This thesis examines how it was possible to integrate these port cities on an economic and on an underlying level of civic mentalities and local identities. Existing studies have often overlooked the importance that Bismarck attributed to the cultural or indeed the ideological re-alignment of Hamburg and Bremen. Therefore, this study will look at the way the people of Hamburg and Bremen traditionally defined their (liberal) identity and the way this changed during the 1870s and 1880s. It will also investigate the role of the acquisition of colonies during the process of Hamburg and Bremen’s accession. In Hamburg in particular, the agreement to join the customs union had a significant impact on the merchants’ stance on colonialism. -

Singapore and Malaysian Armies Conclude Bilateral Military Exercise

Singapore and Malaysian Armies Conclude Bilateral Military Exercise 13 Nov 2016 The Chief of Staff-General Staff of the Singapore Army, Brigadier-General (BG) Desmond Tan Kok Ming and the Deputy Chief of Army of the Malaysian Armed Forces, Lieutenant-General Dato' Seri Panglima Hj Ahmad Hasbullah bin Hj Mohd Nawawi, co-officiated the closing ceremony of Exercise Semangat Bersatu this morning. This year's exercise, the 22nd edition in the series of bilateral exercises between both armies, was conducted in Kluang, Johor from 3 to 13 November 2016. It involved around 980 personnel from both the 1st Battalion, Singapore Infantry Regiment, and the 5th Royal Malay Regiment. The exercise included professional exchanges and culminated in a combined battalion field exercise. In his closing speech, BG Tan said, "Today, the armies of Malaysia and Singapore enjoy a deep and abiding respect for each other. Through our defence relations, we find 1 greater areas of convergence between our two countries and therein forge the basis for a lasting bond… I am heartened to know that our soldiers took the opportunity to interact, to build relationships and achieve a deeper understanding of each other during the last two weeks. Through the professional exchanges and outfield exercise, our soldiers have truly demonstrated our armies' "unity in spirit", or semangat bersatu." First conducted in 1989, Exercise Semangat Bersatu serves as an important and valuable platform for professional exchanges and personnel-to-personnel interactions between the SAF and the MAF. The SAF and the MAF also interact regularly across a wide range of activities, which include bilateral exchanges and professional courses, as well as multilateral activities under the ambit of the ASEAN Defence Ministers' Meeting and the Five Power Defence Arrangements. -

Arms Procurement Decision Making Volume II: Chile, Greece, Malaysia

4. Malaysia Dagmar Hellmann-Rajanayagam* I. Introduction Malaysia has become one of the major political players in the South-East Asian region with increasing economic weight. Even after the economic crisis of 1997–98, despite defence budgets having been slashed, the country is still deter- mined to continue to modernize and upgrade its armed forces. Malaysia grappled with the communist insurgency between 1948 and 1962. It is a democracy with a strong government, marked by ethnic imbalances and affirmative policies, strict controls on public debate and a nascent civil society. Arms procurement is dominated by the military. Public apathy and indifference towards defence matters have been a noticeable feature of the society. Public opinion has disregarded the fact that arms procurement decision making is an element of public policy making as a whole, not only restricted to decisions relating to military security. An examination of the country’s defence policy- making processes is overdue. This chapter inquires into the role, methods and processes of arms procure- ment decision making as an element of Malaysian security policy and the public policy-making process. It emphasizes the need to focus on questions of public accountability rather than transparency, as transparency is not a neutral value: in many countries it is perceived as making a country more vulnerable.1 It is up 1 Ball, D., ‘Arms and affluence: military acquisitions in the Asia–Pacific region’, eds M. Brown et al., East Asian Security (MIT Press: Cambridge, Mass., 1996), p. 106. * The author gratefully acknowledges the help of a number of people in putting this study together. -

Victories Are Not Enough: Limitations of the German Way of War

VICTORIES ARE NOT ENOUGH: LIMITATIONS OF THE GERMAN WAY OF WAR Samuel J. Newland December 2005 Visit our website for other free publication downloads http://www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army.mil/ To rate this publication click here. This publication is a work of the United States Government, as defined in Title 17, United States Code, section 101. As such, it is in the public domain and under the provisions of Title 17, United States Code, section 105, it may not be copyrighted. ***** The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. This report is cleared for public release; distribution is unlimited. ***** My sincere thanks to the U.S. Army War College for approving and funding the research for this project. It has given me the opportunity to return to my favorite discipline, Modern German History, and at the same time, develop a monograph which has implications for today’s army and officer corps. In particular, I would like to thank the Dean of the U.S. Army War College, Dr. William Johnsen, for agreeing to this project; the Research Board of the Army War College for approving the funds for the TDY; and my old friend and colleague from the Militärgeschichliches Forschungsamt, Colonel (Dr.) Karl-Heinz Frieser, and some of his staff for their assistance. In addition, I must also thank a good former student of mine, Colonel Pat Cassidy, who during his student year spent a considerable amount of time finding original curricular material on German officer education and making it available to me. -

Political, Diplomatic and Military Aspects of Romania's Participation in the First World War

Volume XXI 2018 ISSUE no.2 MBNA Publishing House Constanta 2018 SBNA PAPER OPEN ACCESS Political, diplomatic and military aspects of romania's participation in the first world war To cite this article: M. Zidaru, Scientific Bulletin of Naval Academy, Vol. XXI 2018, pg. 202-212. Available online at www.anmb.ro ISSN: 2392-8956; ISSN-L: 1454-864X doi: 10.21279/1454-864X-18-I2-026 SBNA© 2018. This work is licensed under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 License Political, diplomatic and military aspects of romania's participation in the first world war M. Zidaru1 1Romanian Society of Historian. Constanta Branch Abstract: Although linked to the Austro-Hungarian Empire by a secret alliance treaty in 1883, Romania chose to declare itself neutral at the outbreak of hostilities in July 1914, relying on the interpretation of the "casus foederis" clauses. The army was in 1914 -1915 completely unprepared for such a war, public opinion, although pro-Entente in most of it, was not ready for this kind of war, and Ion I. C. Bratianu was convinced that he had to obtain a written assurance from the Russian Empire in view of his father's unpleasant experience from 1877-1878. This article analyze the political and military decisions after Romania entry in Great War. Although linked to the Austro-Hungarian Empire by a secret alliance treaty in 1883, Romania chose to declare itself neutral at the outbreak of hostilities in July 1914, relying on the interpretation of the "casus foederis" clauses. In the south, Romania has three major strategic interests in this region: - defense of the long Danubian border and the land border between the Danube and the Black Sea; - the keep open of the Bosphorus and Dardanelles, through which 90% of the Romanian trade were made; - avoiding the isolation or political encirclement of Romania by keeping open the Thessaloniki-Nis- Danube communication, preventing its blocking as a result of local conflicts or taking over under strict control by one of the great powers in the region[1]. -

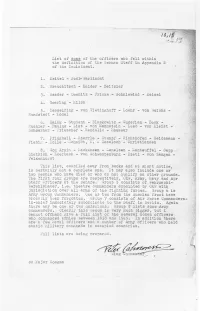

List of Some of the Officers ~~10 Fall Within the Definition of the German

-------;-:-~---,-..;-..............- ........- List of s ome of t he officers ~~10 fall within t he de finition of t he German St af f . in Appendix B· of t he I n cii c tment . 1 . Kei t e l - J odl- Aar l imont 2 . Br auchi t s ch - Halder - Zei t zl er 3. riaeder - Doeni t z - Fr i cke - Schni ewi nd - Mei s el 4. Goer i ng - fu i l ch 5. Kes s el r i ng ~ von Vi et i nghof f - Loehr - von ~e i c h s rtun c1 s t ec t ,.. l.io d eL 6. Bal ck - St ude nt - Bl a skowi t z - Gud er i an - Bock Kuchl er - Pa ul us - Li s t - von Manns t ei n - Leeb - von Kl e i ~ t Schoer ner - Fr i es sner - Rendul i c - Haus s er 7. Pf l ug bei l - Sper r l e - St umpf - Ri cht hof en - Sei a emann Fi ebi £; - Eol l e - f)chmi dt , E .- Des s l och - .Christiansen 8 . Von Arni m - Le ck e ris en - :"emelsen - l.~ a n t e u f f e l - Se pp . J i et i i ch - 1 ber ba ch - von Schweppenburg - Di e t l - von Zang en t'al kenhol's t rr hi s' list , c ompiled a way f r om books and a t. shor t notice, is c ertai nly not a complete one . It may also include one or t .wo neop .le who have ai ed or who do not q ual ify on other gr ounds . -

Assessing the Implications of Possible Changes to Women in Service Restrictions: Practices of Foreign Militaries and Other Organizations

Assessing the Implications of Possible Changes to Women in Service Restrictions: Practices of Foreign Militaries and Other Organizations Annemarie Randazzo-Matsel • Jennifer Schulte • Jennifer Yopp DIM-2012-U-000689-Final July 2012 Photo credit line: Young Israeli women undergo tough, initial pre-army training at Zikim Army Base in southern Israel. REUTERS/Nir Elias Approved for distribution: July 2012 Anita Hattiangadi Research Team Leader Marine Corps Manpower Team Resource Analysis Division This document represents the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the Department of the Navy. Cleared for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. Specific authority: N00014-11-D-0323. Copies of this document can be obtained through the CNA Document Control and Distribution Section at 703-824-2123. Copyright 2012 CNA This work was created in the performance of Federal Government Contract Number N00014-11-D-0323. Any copyright in this work is subject to the Government's Unlimited Rights license as defined in DFARS 252.227-7013 and/or DFARS 252.227-7014. The reproduction of this work for commercial purposes is strictly prohibited. Nongovernmental users may copy and distribute this document in any medium, either commercially or noncommercially, provided that this copyright notice is reproduced in all copies. Nongovernmental users may not use technical measures to obstruct or control the read-ing or further copying of the copies they make or distribute. Nongovernmental users may not accept compensation of any manner in exchange for copies. All other rights reserved. Contents Executive summary . 1 Foreign militaries . 3 Australia . 4 ADF composition . -

Britain and the Greek Security Battalions, 1943-1944

VOL. XV, Nos. 1 & 2 SPRING-SUMMER 1988 Publisher: LEANDROS PAPATHANASIOU Editorial Board: MARIOS L. EVRIVIADES ALEXANDROS KITROEFF PETER PAPPAS YIANNIS P. ROUBATIS Managing Eidtor: SUSAN ANASTASAKOS Advisory Board: MARGARET ALEXIOU KOSTIS MOSKOFF Harvard University Thessaloniki, Greece SPYROS I. ASDRACHAS Nlcos MOUZELIS University of Paris I London School of Economics LOUKAS AXELOS JAMES PETRAS Athens, Greece S.U.N.Y. at Binghamton HAGEN FLEISCHER OLE L. SMITH University of Crete University of Copenhagen ANGELIKI E. LAIOU STAVROS B. THOMADAKIS Harvard University Baruch College, C.U.N.Y. CONSTANTINE TSOUCALAS University of Athens The Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora is a quarterly review published by Pella Publishing Company, Inc., 337 West 36th Street, New York, NY 10018-6401, U.S.A., in March, June, September, and December. Copyright © 1988 by Pella Publishing Company. ISSN 0364-2976 NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS DAVID GILMORE is professor of anthropology at the State Uni- versity of New York at Stony Brook . MOLLY GREENE is a doc- toral candidate at Princeton University . CLIFFORD P. HACKETT is a former aide to U.S. Representative Benjamin Rosenthal and Senator Paul Sarbanes. He is currently administering an exchange program between the U.S. Congress and the European Parliament and is also executive director of the American Council for Jean Monnet Studies . JOHN LOUIS HONDROS is professor of history at the College of Wooster, Ohio ... ADAMANTIA POLLIS is professor of political science at the Graduate Faculty of the New School for Social Re- search . JOHN E. REXINE is Charles A. Dana Professor of the Classics and director of the division of the humanities at Colgate Uni- versity . -

ABSTRACT Title of Document: the FURTHEST

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE FURTHEST WATCH OF THE REICH: NATIONAL SOCIALISM, ETHNIC GERMANS, AND THE OCCUPATION OF THE SERBIAN BANAT, 1941-1944 Mirna Zakic, Ph.D., 2011 Directed by: Professor Jeffrey Herf, Department of History This dissertation examines the Volksdeutsche (ethnic Germans) of the Serbian Banat (northeastern Serbia) during World War II, with a focus on their collaboration with the invading Germans from the Third Reich, and their participation in the occupation of their home region. It focuses on the occupation period (April 1941-October 1944) so as to illuminate three major themes: the mutual perceptions held by ethnic and Reich Germans and how these shaped policy; the motivation behind ethnic German collaboration; and the events which drew ethnic Germans ever deeper into complicity with the Third Reich. The Banat ethnic Germans profited from a fortuitous meeting of diplomatic, military, ideological and economic reasons, which prompted the Third Reich to occupy their home region in April 1941. They played a leading role in the administration and policing of the Serbian Banat until October 1944, when the Red Army invaded the Banat. The ethnic Germans collaborated with the Nazi regime in many ways: they accepted its worldview as their own, supplied it with food, administrative services and eventually soldiers. They acted as enforcers and executors of its policies, which benefited them as perceived racial and ideological kin to Reich Germans. These policies did so at the expense of the multiethnic Banat‟s other residents, especially Jews and Serbs. In this, the Third Reich replicated general policy guidelines already implemented inside Germany and elsewhere in German-occupied Europe. -

Managing an Identity Crisis: Forum Guide to Implementing New Federal Race and Ethnicity Categories (NFES 2008- 802)

FORUM GUIDE TO IMPLEMENTING NEW FEDERAL RACE AND ETHNICITY CATEGORIES 2008 NFES 2008–802 U.S. Department of Education ii National Cooperative Education Statistics System The National Center for Education Statistics established the National Cooperative Education Statistics System (Cooperative System) to assist in producing and maintaining comparable and uniform information and data on early childhood education and elementary and secondary education. These data are intended to be useful for policymaking at the federal, state, and local levels. The National Forum on Education Statistics, among other activities, proposes principles of good practice to assist state and local education agencies in meeting this purpose. The Cooperative System and the National Forum on Education Statistics are supported in these endeavors by resources from the National Center for Education Statistics. Publications of the National Forum on Education Statistics do not undergo the formal review required for products of the National Center for Education Statistics. The information and opinions published here are the product of the National Forum on Education Statistics and do not necessarily represent the policy or views of the U.S. Department of Education or the National Center for Education Statistics. October 2008 This publication and other publications of the National Forum on Education Statistics may be found at the National Center for Education Statistics website. The NCES World Wide Web Home Page is http://nces.ed.gov. The NCES World Wide Web Electronic Catalog is http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch. The Forum World Wide Web Home Page is http://nces.ed.gov/forum. Suggested Citation National Forum on Education Statistics, Race/Ethnicity Data Implementation Task Force. -

Füakreflexionen Nr 6

Zeitschrift der Begrüßungsrede des Kommandeurs zum Festakt Seite 9 Führungsakademie Generalmajor Wolf-Dieter Löser Kommandeur FüAkBw der Bundeswehr Literaturempfehlungen Seite 12 Impressum Seite 12 Gneisenaus „Tafelrunde“, Josef Schneider, Mainz 1815 Nr. 8 September 2007 Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort Seite 2 Generalmajor Wolf-Dieter Löser Kommandeur FüAkBw 50 Jahre Führungsakademie der Bundeswehr Seite 2 SG Benny Uhder FüAkBw Presse und Öffentlichkeitsarbeit Festrede zum Festakt am 14.09.2007 Seite 4 Bundespräsident Horst Köhler September 2007 • FüAk – Reflexionen – Nr 8, Seite 2 Vorwort Thema Generalmajor Wolf-Dieter Löser SG Benny Uhder FüAkBW Presse und Öffentlichkeitsarbeit Sehr geehrte Damen und Herren, liebe Freunde der A- 50 Jahre Führungsakademie der Bundeswehr kademie, 50 Jahre Führungsakademie der Bundeswehr – ein stolzes und auch für mich I Veranstaltungen im Jubiläumsjahr persönlich bedeutsames Jubiläum. 50 Jahre bildet die Führungsakademie den Der Festakt „50 Jahre Führungsakademie der Bundeswehr“ mit Bun- Führungsnachwuchs der deutschen Streitkräfte aus - bildet ihn umfassend despräsident Dr. Horst Köhler war der Höhepunkt in einer Reihe von aus, nicht nur im militärischen Handwerk, sondern auch im Sinne einer über- greifenden Bildung – mit Blick „über den Tellerrand“, denn das ist es, was un- Jubiläumsveranstaltungen. Den Auftakt bildete im Mai das zweitägige sere Führer in schnell wechselnden Szenarien benötigen, um erfolgreich zu Baudissin-Symposium aus Anlass des 100. Geburtstags Generalleut- handeln. Dabei hat sich die Ausbildung immer wieder den sich verändernden nant Wolf Graf von Baudissins. Das Symposium mit Vertretern aus Rahmenbedingungen und Erfordernissen angepasst. Wissenschaft und Militär, befasste sich mit dem Erbe des Vordenkers Ein halbes - wie man uns sagt erfolgreiches - Jahrhundert Führungsakademie der Inneren Führung. Ebenfalls im Mai 2007 lud die Hamburgische der Bundeswehr war für uns Anlass genug, in einer Reihe von Veranstaltun- Bürgerschaft die Akademie in das Hamburger Rathaus. -

Amphibious and Special Operations in the Aegean Sea 1943-1945 : Operational Effectiveness and Strategic Implications

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive DSpace Repository Theses and Dissertations 1. Thesis and Dissertation Collection, all items 2003-12 Amphibious and special operations in the Aegean Sea 1943-1945 : operational effectiveness and strategic implications Gartzonikas, Panagiotis Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/6200 Downloaded from NPS Archive: Calhoun MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS AMPHIBIOUS AND SPECIAL OPERATIONS IN THE AEGEAN SEA 1943-1945. OPERATIONAL EFFECTIVENESS AND STRATEGIC IMPLICATIONS by Panagiotis Gartzonikas December 2003 Thesis Advisor: Douglas Porch Second Reader: David Tucker Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED December 2003 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE Amphibious and Special Operations in the Aegean Sea 5. FUNDING NUMBERS 1943-1945. Operational Effectiveness and Strategic Implications 6. AUTHOR(S) Panagiotis Gartzonikas 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING Naval Postgraduate School ORGANIZATION REPORT Monterey, CA 93943-5000 NUMBER 9.