An Account of Past and Contemporary Conditions and Progress in Asia, Ex- Cepting China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Papéis Normativos E Práticas Sociais

Agnes Ayres (1898-194): Rodolfo Valentino e Agnes Ayres em “The Sheik” (1921) The Donovan Affair (1929) The Affairs of Anatol (1921) The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Highball Broken Hearted (1929) Cappy Ricks (1921) (1918) Bye, Bye, Buddy (1929) Too Much Speed (1921) Their Godson (1918) Into the Night (1928) The Love Special (1921) Sweets of the Sour (1918) The Lady of Victories (1928) Forbidden Fruit (1921) Coals for the Fire (1918) Eve's Love Letters (1927) The Furnace (1920) Their Anniversary Feast (1918) The Son of the Sheik (1926) Held by the Enemy (1920) A Four Cornered Triangle (1918) Morals for Men (1925) Go and Get It (1920) Seeking an Oversoul (1918) The Awful Truth (1925) The Inner Voice (1920) A Little Ouija Work (1918) Her Market Value (1925) A Modern Salome (1920) The Purple Dress (1918) Tomorrow's Love (1925) The Ghost of a Chance (1919) His Wife's Hero (1917) Worldly Goods (1924) Sacred Silence (1919) His Wife Got All the Credit (1917) The Story Without a Name (1924) The Gamblers (1919) He Had to Camouflage (1917) Detained (1924) In Honor's Web (1919) Paging Page Two (1917) The Guilty One (1924) The Buried Treasure (1919) A Family Flivver (1917) Bluff (1924) The Guardian of the Accolade (1919) The Renaissance at Charleroi (1917) When a Girl Loves (1924) A Stitch in Time (1919) The Bottom of the Well (1917) Don't Call It Love (1923) Shocks of Doom (1919) The Furnished Room (1917) The Ten Commandments (1923) The Girl Problem (1919) The Defeat of the City (1917) The Marriage Maker (1923) Transients in Arcadia (1918) Richard the Brazen (1917) Racing Hearts (1923) A Bird of Bagdad (1918) The Dazzling Miss Davison (1917) The Heart Raider (1923) Springtime à la Carte (1918) The Mirror (1917) A Daughter of Luxury (1922) Mammon and the Archer (1918) Hedda Gabler (1917) Clarence (1922) One Thousand Dollars (1918) The Debt (1917) Borderland (1922) The Girl and the Graft (1918) Mrs. -

And the Cement Is Tempered

Issue 7 January 2014 POLITICAL ANALYSIS AND COMMENTARY TURKEY URBAN TRANSFORMATION AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT TOWARDS THE ELECTIONS And the cement is tempered Ecology 28 International Politics 52 Culture 58 Slow philosophy The hedging strategy in foreign policy Gezi’s universe of possibilities Rıdvan Yurtseven M.Sinan Birdal Ezgi Bakçay Contents 3 Editorial URBAN TRANSRORMATION AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT TOWARDS THE ELECTIONS 4 Gezi, elections and a political alternative, Stefo Benlisoy 9 HDP: Possibilities and obstacles, Ayhan Bilgen 14 Autonomy in local government, Hacı Kurt 19 Crazy urban transformation, rational capital accumulation, Gökhan Bilgihan 24 Weakening the local, reinforcing the center, Prof. Dr. Nadir Suğur ECOLOGY 28 Slow philosophy, Rıdvan Yurtseven 33 Çıralı: Paradise lost, Yusuf Yavuz DEMOCRACY 36 Democratization package evaluated with the independent criteria prevalent in democracies, Ayşen Candaş 41 Violence Prevention and Monitoring Centers (ŞÖNİM) that can’t (won’t) prevent male violence, Deniz Bayram 46 The German political associations - demon and enemy of Turkey? Ulrike Dufner 48 In praise of Turkishness - an end in sight?, Özgür Sevgi Göral INTERNATIONAL POLITICS 52 The hedging strategy in foreign policy, M.Sinan Birdal CULTURE 58 Gezi’s universe of possibilities, Ezgi Bakçay HUMAN LANDSCAPE 65 Wooden-sworded knight of the last Roman castle, or the cry of a human rights defender, Muherrem Erbey 69 News from hbs Heinrich Böll Stiftung - Turkey Represantation The Heinrich Böll Stiftung, associated with the German Green Party, is a legally autonomous and intellectually open political foundation. Our foremost task is civic education in Germany and abroad with the aim of promoting informed democratic opinion, socio-political commitment and mutual understanding. -

Download File

Beulah Marie Dix Also Known As: Mrs. George H. Flebbe Lived: December 25, 1876 - September 25, 1970 Worked as: adapter, novelist, playwright, screenwriter, title writer, writer Worked In: United States by Wendy Holliday Beulah Marie Dix became a writer because it was one of the few respectable options available for women in the early twentieth century. The daughter of a factory foreman from an old New England family, Dix was educated at Radcliffe College, where she graduated with honors and became the first woman to win the prestigious Sohier literary prize. Instead of teaching, she decided to write after she sold some stories to popular magazines. She wrote mainly historical fiction, including novels and children’s books. In 1916, she went to California to visit her theatre agent, Beatrice deMille, mother of film pioneers Cecil and William, who had moved there with the Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Film Company, which was that year to become Famous Players-Lasky after a merger with Adolph Zukor’s Famous Players. Dix decided to experiment with writing for the new motion picture industry just for fun, but became a successful and productive silent era scenario writer, as her daughter, Evelyn Flebbe Scott, recalled (7-9). She began writing for William deMille because, according to her daughter, Evelyn Flebbe Scott, Dix felt he was a “dramatist of equal standing with herself” (47). She became especially known for her ability to write strong historical characters, and she had a flare for writing scenes of violence. Her initial experiments turned into a full-time writing job, and she was placed under contract at Famous Players-Lasky, soon Paramount Pictures. -

Photoplay142chic

b U? 1 .i i \r\l\ /I m of Modern Art Scanned from the collection of The Museum of Modern Art Library Coordinated by the Media History Digital Library www.mediahistoryproject.org Funded by a donation from David Sorochty Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/photoplay142chic zMary Thur-inan Photoplay Magazine—Advkrtisino Section 3 1 I Th,The worlds best guide book ! totO the enjoyment of music Entertaining Instructive Convenient Are you familiar with the story of the opera of Rigoletto? Of Faust? Of Pagliacci? Do you know the national airs of Denmark and China? Do you know which Kipling ballads have been set to music? Did you know that Chopin was pronounced a genius at eight years of age? Information on all these subjects is to be found within the 510 pages of the Victor Record catalog. It presents in alphabetical order, cross indexed, the thou- sands of Victor Records which comprise the greatest library of music in all the world. But besides that it abounds with interesting musical knowledge which "HIS MASTER'S VOICE" bco- o s p*t orr. adds greatly to your enjoyment of all music. It is a This trademark ami the tradeniarked word every music-lover will and there is "Victrola" identify all our products. Look under book want, a copy the lid! Look on the label' for you at your Victor dealer's. Or write to us and we VICTOR TALKING MACHINE CO. Camden, N. J. will gladly mail a copy to you. Victor Talking Machine Company, Camden,N.j. -

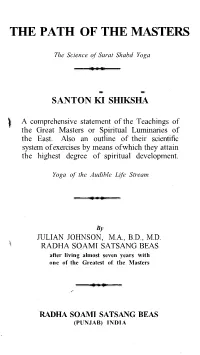

The Path of the Masters

THE PATH OF THE MASTERS The Science of Surat Shabd Yoga SANTON KI SHIKSHA A comprehensive statement of the Teachings of the Great Masters or Spiritual Luminaries of the East. Also an outline of their scientific system of exercises by means of which they attain the highest degree of spiritual development. Yoga of the Audible Life Stream By JULIAN JOHNSON, M.A., B.D., M.D. RADHA SOAMI SATSANG BEAS after living almost seven years with one of the Greatest of the Masters RADHA SOAMI SATSANG BEAS (PUNJAB) INDIA THE AUTHOR A typical Kentuckyan, a distinguished artist, a devout theologian, an ardent flier, an outstanding surgeon and above all a keen seeker after truth, Dr. Julian Johnson, sacrificing his all at a time when he was at the height of his worldly fame, came to answer the call of the East for the second time. The first time was when he voyaged to India to preach the true gospel of Lord Jesus Christ in his inimitable way. He came to enlighten her but eventually had to receive enlighten- ment from her. Caesar came, saw and conquered; the author came, saw and was conquered. It was a day of destiny for him when he came the second time. He was picked up, as it were, from a remote corner and guided to the feet of the Master. Once there, he never left. He assiduously carried out the spiritual discipline taught by one of the greatest living Masters and was soon rewarded. He had the vision of the Reality beyond all forms and ceremonies. -

The Call of the East

THE CALL OF THE EAST THURLOW FRASER CHAPTER I. STORM SIGNALS. "Pardon me, Miss MacAllister! Is there any way in which I can be of service to you?" The young lady addressed turned quickly from the deck-rail on which she had been leaning, and with a defiant toss of her head faced her questioner. A hot flush of resentment chased from her face the undeniable pallor of a moment before. "In what way do you think you can be of service to me, Mr. Sinclair?" she demanded sharply. "I thought that you were ill, and——" "And is it so uncommon to be sea-sick, or is it such a dangerous ailment, that at the first symptom the patient must be cared for as if she had the plague?" "Perhaps not! But I am told that it is uncomfortable." There was a humorous twinkle in his eyes. At the sight of it hers flashed, and the flame of her anger rose higher. "From that I am to understand, Mr. Sinclair, that you are one of those superior beings who never suffer from sea-sickness." "I must confess to belonging to that class," he replied good-humouredly. "I have never experienced its qualms." "Then I abominate such people. They call themselves 'good sailors.' They offer sympathy to others, and all the while are laughing in their sleeves. They are insufferable prigs. I want none of their sympathy." "But, Miss MacAllister, you misunderstand me. I am not offering you empty sympathy. I am a medical doctor, and for the present am in charge of the health of the passengers on this ship." "Then, Dr. -

The STORY of the Famous Players-Lasky Corporation L

. ^^r -".«*»». FAMOUS P1AYERS-LASKY CORPORATION ADOLPM ZUKOR mm. JESSE t.LASKY H»Aw CECIt B.OE MILLE IWrti'C«i««l I TUWYOMl, LIBRARY Brigham Young University RARE BOOK COLLECTION Rare Quarto PN ^r1999 1919 I The STORY of the Famous Players-Lasky Corporation l : i ll ! . .; ,i i i i i)i ! ]il lll) llll l l l lllllll l [|||||IHl H MiilMii 3ES ==?r .:;.Mii !llll li im 3E 1 I i I Walter E. Greene /''ice-President ! Frank A. Garbott Vice-President t I 'l|i"l|!l||||ii 2Z^ ^^ illillllllllllllllllllllllllllllillllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllHlllllllllllllllllll 2ff 3C JZ The Story of the Famous Players-Lasky Corporation (paramount~Qricra£t ^Motion (pictures -...or ..»«*» FAMOUS PLAYERS-LASKY CORPORATION <L ADOLPH ZUKOR Pres JESSE L.LASKY VkxPrms. CECIL B DE M1LLE Director Cenerol. "NEW YORIC Copyright, IQIQ, by the Famous Players-Lasky Corporation ~ZL M : 1 TTT- I'liiiiiiii'iiiiiiiiMiiiiiiii, 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 t < 1 iii 35 i : ; 1 1 i 1 1 > 1 . 1 W=] s: .^sm: '":;iii!!'i'i:'iniiiii""!"i. ! ":"''.t iiinu'lM u m 3 i i S i 5 1 i im :=^ !l!l!llllllll!lllllli^ 3T Adolph Zukor, President ^t^-Q INTRODUCTION 1 HIS is the complete story of the Famous Players-Lasky Corporation, the world's greatest motion picture enterprise. The story of the Famous Players-Lasky Corporation is the story of the motion picture. For it is this organization which has made the motion picture. Seven years ago, Adolph Zukor saw in the motion picture, then only an amusing toy, amazing and tremendous possibilities. -

1 Title Page

UNIVERSITY OF READING An Invitation to Travel The Marketing and Reception of Japanese Film in the West 1950-1975 Submitted for Ph.D. degree Department of Film, Theatre & Television Boel Ulfsdotter March 2008 ABSTRACT An Invitation to Travel – The Marketing and Reception of Japanese Film in the West 1950-1975 is a reception study which presents the events and efforts that characterize the reception of Japanese film in France, Great Britain and the United States, after World War Two. Chapter One presents the research questions informing this study and discusses the historically located Western cultural concepts involved such as the aesthetics of art cinema, Japonisme, and the notion of ‘Japaneseness’. The argumentation as such is based on the presumption of a still prevailing Orientalist discourse at the time. The thesis discusses the Japanese film industry’s need to devise a new strategy of doing export business with the West in relation to the changed postwar context in Chapter Two. The preparations on the part of the Japanese to distribute their films in the West through different modes of transnational publicity are in focus here, from introductory ‘film weeks’, to marketing vehicles such as UniJapan Film Quarterly, and the first Western books on Japanese film history. The thesis then proceeds to deal with the groundbreaking introduction of this first non-occidental national cinema from four different angles; exhibition (Chapter Three), critical reception (Chapter Four), publicity (Chapter Five) and canon formation (Chapter Six). Chapter Three looks into the history of Western exhibition of Japanese film in the countries involved in this study and identifies divergent attitudes between institutional and commercial screenings. -

Kintaro Hayakawa (June 10, 1886-November 23, 1973) Known Professionally As Sessue Hayakawa Was a Japanese Actor and a Matinee Idol

Kintaro Hayakawa (June 10, 1886-November 23, 1973) known professionally as Sessue Hayakawa was a Japanese actor and a matinee idol. He was one of the biggest stars in Hollywood during the silent film era of the 1910s and early 1920s. Hayakawa was the first actor of Asian descent to achieve stardom as a leading man in the United States and Europe. Thanks to the Gospel of Hollywood - Movie goers see every Yellow face they encounter as either A two-faced Jap spy with a round face and round glasses or bald headed, buck toothed and Tojo mustache. Or acted by a White man as a goodie good Charlie Chan ,who kills his Chinese self and lives on as Our Father Who Art in Hollywood, leading the Godless Yellow to White Supremacy , Assimilation and God. Belief in a power over one’s self, outside of the family to a Taoist, a Confucian is unthinkable. Stupid. A meeting between members of the same family strikes lightning in the brain. That attracts or repels. Momoko Iko refers to “household gods” , a term that resonates comfortably with Japanese and Chinese of the generation of 1940. MOVIES BEGIN WITH SESSUE HAYAKAWA – TV BEGINS WITH GEORGE TAKEI – TAKEI TAKES TV AMERICA TO – AA LITERATURE BY STEALING A SHARE OF RANDALL DUK KIM’S PERFORMANCE OF A TOURIST GUIDE IN FRANK CHIN’S “THE YEAR OF THE DRAGON “ ON PBS – AND TAKEI IS AS SIGNIFICANT AS HAYAKAWA IN AA LITERARY, SHOWBIZ, ENTERTAINMENT HISTORY. REALLY? RANDALL KIM MAKES A MIDWESTERN AN INTERNATIONAL REP AS A SHAKESPEAREAN ACTOR & TEACHER, AND HAS A SHAKESPEAREAN THEATER OUTSIDE OF MILWAUKEE BUT TAKEI IS INVITED TO LECTURE THE SHAKESPEARE CO IN LONDON. -

George Melford Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

George Melford 电影 串行 (大全) Freedom of the Press https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/freedom-of-the-press-20092777/actors Told in the Hills https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/told-in-the-hills-3992387/actors Rocking Moon https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/rocking-moon-55631890/actors Lingerie https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/lingerie-60737773/actors Sinners in Love https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/sinners-in-love-30593511/actors The Boer War https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-boer-war-7719015/actors The Invisible Power https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-invisible-power-21648734/actors Men, Women, and Money https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/men%2C-women%2C-and-money-18915104/actors A Celebrated Case https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-celebrated-case-3602370/actors Jane Goes A-Wooing https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/jane-goes-a-wooing-6152285/actors Shannon of the Sixth https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/shannon-of-the-sixth-20005977/actors The Skeleton in the Closet https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-skeleton-in-the-closet-20803275/actors The Mountain Witch https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-mountain-witch-20803094/actors Jungle Menace https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/jungle-menace-10312965/actors A Scarlet Week-End https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-scarlet-week-end-106401496/actors East of Borneo https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/east-of-borneo-1167721/actors The City of Dim Faces https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-city-of-dim-faces-13423760/actors