As the Movie Business Founders, Adam Fogelson Tries to Reinvent the System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLAAD Media Institute Began to Track LGBTQ Characters Who Have a Disability

Studio Responsibility IndexDeadline 2021 STUDIO RESPONSIBILITY INDEX 2021 From the desk of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis In 2013, GLAAD created the Studio Responsibility Index theatrical release windows and studios are testing different (SRI) to track lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and release models and patterns. queer (LGBTQ) inclusion in major studio films and to drive We know for sure the immense power of the theatrical acceptance and meaningful LGBTQ inclusion. To date, experience. Data proves that audiences crave the return we’ve seen and felt the great impact our TV research has to theaters for that communal experience after more than had and its continued impact, driving creators and industry a year of isolation. Nielsen reports that 63 percent of executives to do more and better. After several years of Americans say they are “very or somewhat” eager to go issuing this study, progress presented itself with the release to a movie theater as soon as possible within three months of outstanding movies like Love, Simon, Blockers, and of COVID restrictions being lifted. May polling from movie Rocketman hitting big screens in recent years, and we remain ticket company Fandango found that 96% of 4,000 users hopeful with the announcements of upcoming queer-inclusive surveyed plan to see “multiple movies” in theaters this movies originally set for theatrical distribution in 2020 and summer with 87% listing “going to the movies” as the top beyond. But no one could have predicted the impact of the slot in their summer plans. And, an April poll from Morning COVID-19 global pandemic, and the ways it would uniquely Consult/The Hollywood Reporter found that over 50 percent disrupt and halt the theatrical distribution business these past of respondents would likely purchase a film ticket within a sixteen months. -

06 MPLC US Producer List by Product

4/2/2019 LIB LIB The MPLC producer list is broken down into seven genres for your programming needs. Subject to the Umbrella License ® Terms and Conditions, Licensee may publicly perform copyrighted motion pictures and other audiovisual programs intended for personal use only, from the list of producers and distributors below in the following category: Public Libraries MAJOR HOLLYWOOD STUDIOS & AFFILIATED LABELS Fox - Walden Fox 2000 Films Fox Look Fox Searchlight Pictures STX Entertainment Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. CHILDRENS Central Park Media Cosgrove Hall Films D'Ocon Family Entertainment Library Harvey Entertainment McGraw-Hill Peter Pan Video Scholastic Entertainment FAITH-BASED Alley Cat Films American Portrait Films Big Idea Entertainment Billy Graham Evangelistic Ass. / World British and Foreign Bible Society Candlelight Media Wide Pictures CDR Communications Choices, Inc. Christian Television Association Cross Wind Productions Crossroad Motion Pictures Crown Entertainment D Christiano Films DBM Films Elevation EO International ERF Christian Radio & Television Eric Velu Productions Gateway Films Gospel Films Grace Products/Evangelical Films Grizzly Adams Productions Harvest Productions International Christian Communications (ICC) International Films Jeremiah Films Kalon Media, Inc. Kingsway Communications Lantern Film and Video Linn Productions Mahoney Media Group, Inc. Maralee Dawn Ministries McDougal Films 4/2/2019 LIB LIB The MPLC producer list is broken down into seven genres for your programming needs. Subject to the -

Actor Network Theory Analysis of Roc Climbing Tourism in Siurana

MASTER THESIS Actor network theory analysis of sport climbing tourism The case of Siurana, Catalunya Student: Jase Wilson Exam #: 19148985 Supervisor: Professor Tanja Mihalič PhD. Generalitat de Catalunya Mentor: Cati Costals Submitted to: Faculty of Economics University of Ljubljana, Slovenia Submitted on: August 4th, 2017 This page has been left internationally blank. AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT The undersigned _____________________, a student at the University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Economics, (hereafter: FELU), declare that I am the author of the bachelor thesis / master’s thesis /doctoral dissertation entitled________ ____________________________________________, written under supervision of _______________________________________________ and co-supervision of _________________________________________. In accordance with the Copyright and Related Rights Act (Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia, Nr. 21/1995 with changes and amendments) I allow the text of my bachelor thesis / master’s thesis / doctoral dissertation to be published on the FELU website. I further declare • the text of my bachelor thesis / master’s thesis / doctoral dissertation to be based on the results of my own research; • the text of my bachelor thesis / master’s thesis / doctoral dissertation to be language- edited and technically in adherence with the FELU’s Technical Guidelines for Written Works which means that I • cited and / or quoted works and opinions of other authors in my bachelor thesis / master’s thesis / doctoral dissertation in accordance with the FELU’s Technical Guidelines for Written Works and • obtained (and referred to in my bachelor thesis / master’s thesis / doctoral dissertation) all the necessary permits to use the works of other authors which are entirely (in written or graphical form) used in my text; • to be aware of the fact that plagiarism (in written or graphical form) is a criminal offence and can be prosecuted in accordance with the Criminal Code (Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia, Nr. -

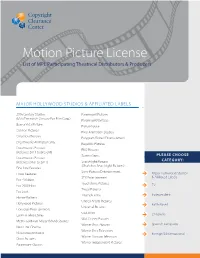

Motion Picture License List of MPL Participating Theatrical Distributors & Producers

Motion Picture License List of MPL Participating Theatrical Distributors & Producers MAJOR HOLLYWOOD STUDIOS & AFFILIATED LABELS 20th Century Studios Paramount Pictures (f/k/a Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp.) Paramount Vantage Buena Vista Pictures Picturehouse Cannon Pictures Pixar Animation Studios Columbia Pictures Polygram Filmed Entertainment Dreamworks Animation SKG Republic Pictures Dreamworks Pictures RKO Pictures (Releases 2011 to present) Screen Gems PLEASE CHOOSE Dreamworks Pictures CATEGORY: (Releases prior to 2011) Searchlight Pictures (f/ka/a Fox Searchlight Pictures) Fine Line Features Sony Pictures Entertainment Focus Features Major Hollywood Studios STX Entertainment & Affiliated Labels Fox - Walden Touchstone Pictures Fox 2000 Films TV Tristar Pictures Fox Look Triumph Films Independent Hanna-Barbera United Artists Pictures Hollywood Pictures Faith-Based Universal Pictures Lionsgate Entertainment USA Films Lorimar Telepictures Children’s Walt Disney Pictures Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Studios Warner Bros. Pictures Spanish Language New Line Cinema Warner Bros. Television Nickelodeon Movies Foreign & International Warner Horizon Television Orion Pictures Warner Independent Pictures Paramount Classics TV 41 Entertaiment LLC Ditial Lifestyle Studios A&E Networks Productions DIY Netowrk Productions Abso Lutely Productions East West Documentaries Ltd Agatha Christie Productions Elle Driver Al Dakheel Inc Emporium Productions Alcon Television Endor Productions All-In-Production Gmbh Fabrik Entertainment Ambi Exclusive Acquisitions -

2018 Catalog

2018 movie CATALOG © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. © 2017 Disney/Pixar SWANK.COM 1.800.876.5577 © Open Road Films © Universal Studios © Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. © Lions Gate Entertainment, Inc. Movie Category Guide PG PG PG PG PG PG G PG PG PG The War with Grandpa PG PG PG-13 PG PG PG PG PG-13 TV-G PG PG PG PG PG PG-13 PG-13 PG-13 PG-13 PG-13 PG-13 Family-Friendly Programming Family-Friendly PG-13 PG-13 PG-13 PG © 2017 Disney/Pixar © 2017 Disney/Pixar © 2017 Disney/Pixar © 2017 Disney/Pixar © 2017 Disney/Pixar © 2017 Disney/Pixar © 2017 Disney/Pixar © 2017 Disney/Pixar © 2017 Disney/Pixar © 2017 Disney/Pixar PG-13 PG-13 PG-13 PG-13 PG-13 PG-13 PG-13 PG-13 PG-13 PG-13 © 2017 Disney/Pixar © 2017 Disney/Pixar © 2017 Disney/Pixar © 2017 Disney/Pixar © 2017 Disney/Pixar © 2017 Disney/Pixar © 2017 Disney/Pixar © 2017 Disney/Pixar © 2017 Disney/Pixar © 2017 Disney/Pixar PG-13 PG PG-13 PG-13 PG-13 PG-13 PG-13 TV-G PG-13 PG-13 © 2017 Disney/Pixar © 2017 Disney/Pixar © 2017 Disney/Pixar © 2017 Disney/Pixar © 2017 Disney/Pixar © 2017 Disney/Pixar © 2017 Disney/Pixar © 2017 Disney/Pixar © 2017 Disney/Pixar Teen/Adult Programming Teen/Adult PG-13 PG-13 PG-13 PG-13 PG PG-13 PG-13 PG-13 PG All trademarks are property of their repective owners. MP9188 Find our top 25 most requested throwback movies on page 31 NEW Releases NEW RELEASES © 2017 Disney/Pixar © Warner Bros. -

DISNEYLAND Grand Opening on 7/17/1955 the Happiest Place on Earth Wasn't Anything of the Sort for 13 Months of Pandemic Closure

Monday, July 19, 2021 | No. 177 Film Flashback…DISNEYLAND Grand Opening on 7/17/1955 The Happiest Place on Earth wasn't anything of the sort for 13 months of pandemic closure. But, happily, Disneyland began coming back to life in late April and by June 15 wasn't facing any capacity restrictions. Now it's celebrating the 66th anniversary of its Grand Opening July 17, 1955. To help finance Disneyland's construction in Anaheim, Calif., which began July 16, 1954, Walt Disney struck a deal with the then fledgling ABC-TV Network to produce the legendary DISNEYLAND series. For helping Walt raise the $17M he needed -- about $135M today -- ABC also got the right to broadcast the opening day events. Originally, July 17 was just an International Press Preview and July 18 was to be the official launch. But July 17's been remembered over the years as the Big Day thanks to ABC's live coverage -- despite things not having gone well with the show hosted by Walt's Hollywood pals Art Linkletter, Bob Cummings & Ronald Reagan. Live TV was in its infancy then and the miles of camera cables it used had people tripping all over the park. In Frontierland, a camera caught Cummings kissing a dancer. Walt was reading a plaque in Tomorrowland on camera when a technician started talking to him, causing Walt to stop and start again from the beginning. Over in Fantasyland, Linkletter sent the coverage back to Cummings on a pirate ship, but Bob wasn't ready, so he sent it right back to Art, who no longer had his microphone. -

Movers & Shakers Email Alert

Movers & Shakers Email Alert 1 Visit Variety Business Intelligence at NATPE in Miami January 16-18 or Realscreen East in Washington D.C. January 28-31. Click here to set a meeting! We’re proud to congratulate the following movers & shakers: Corporate: Fukiko Ogisu Now: Executive Vice President and Chief People Officer, Viacom (New York) Was: Senior Vice President, HR Business Operations & Information Solutions, Viacom (New York) Digital: Julie DeTraglia Now: Vice President and Head, Research, Hulu (New York) Was: Head, Ad Sales Research, Hulu (New York) Jenny Wall Now: Chief Marketing Officer, Gimlet Media (Brooklyn) Was: Senior Vice President and Head, Marketing, Hulu Film: Toby Emmerich Now: Chairman, Warner Bros. Pictures Group Was: President and Chief Content Officer, Warner Bros. Pictures Group Stacy Glassgold Now: Vice President, International Sales, XYZ Films Was: Vice President, Sales & Distribution, Myriad Pictures Walter Hamada Now: President, DC-Based Film Production, Warner Bros. Pictures Was: Executive Vice President, Production, New Line Cinema Sue Kroll Now: Transitioning to producing role (as of April 1st, 2018) Was: President, Worldwide Marketing & Distribution, Warner Bros. Pictures Group Michelle Krumm Now: Head, Australian Operations & Worldwide Acquisitions, Arclight Films (Sydney) Was: Head, Production, Development & Studios, South Australian Film Corp (Glenside) Alana Mayo Now: Head, Production & Development, Outlier Society Productions Was: Vice President and Head, Originals, Vimeo Ashley Momtaheni Now: Vice President, Communications, Annapurna Pictures Was: Director, Marketing & Publicity, Annapurna Pictures 2 Pip Ngo Now: Director, Acquisitions & Sales, XYZ Films Was: Senior Manager, Content Acquisition & Business Development, Vimeo Michael Pavlic Now: President, Creative Advertising, Annapurna Pictures Was: President, Worldwide Creative Advertising, Sony Pictures Entertainment Blair Rich Now: President, Worldwide Marketing, Warner Bros. -

DATE Name Company Address Dear , SWANK MOTION PICTURES, INC

10795 Watson Road Barbara Nelson Saint Louis, MO 63127-1012 Vice President 800-876-5577 314-984-6130 Email: [email protected] DATE Name Company Address Dear , SWANK MOTION PICTURES, INC. is the sole source for non-theatrical distribution and public performance licensing to Colleges and Universities, Elementary, High schools, Park and Recreation Departments, Cruise Ships, Hospitals and various other non-theater settings in either 35mm film, Pre-home DVD, DVD’s, Blu-Ray DVD and digital formats for the following studios: Warner Brothers The Weinstein Company Warner Independent Pictures A24 Films New Line Cinema Bleecker Street Media Columbia Pictures (Sony) STX Entertainment TriStar Pictures HBO Pictures Walt Disney Pictures CBS Films Marvel Entertainment Cohen Media Group Touchstone Hallmark Hall of Fame Universal Pictures IFC Films Focus Features Magnolia Pictures Paramount Pictures Monterey Media Lionsgate RLJ Entertainment Summit Entertainment Samuel Goldwyn Metro-Goldwyn Mayer United Artists Miramax The Orchard Studios listed are those supplying titles at the time of this printing, and since studios may vary from year to year, it is possible that one major studio may be added or one deleted. Any film that your organization licenses from Swank Motion Pictures for non-theatrical public performance and which is distributed by the motion picture studios listed above is fully in compliance with the Copyright Act as stated in Title 17 of the United States Code. Sincerely, Barbara J. Nelson VP, Sales and Studio Relations Worldwide Non-Theatrical Distributors of Motion Pictures www.swank.com . -

Reel Rock Press Release

It’s been a big year in climbing – from Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson’s epic saga on the Dawn Wall to the tragic loss of Dean Potter, one of the sport’s all-time greats. In our 10th year, the REEL ROCK Film Tour will celebrate them all with an incredible lineup of films that go beyond the headlines to stories that are both intimate and awe-inspiring. REEL ROCK 10 FILM LINEUP A LINE ACROSS the SKY 35 mins The Fitz Roy traverse is one of the most sought after achievements in modern alpinism: a gnarly journey across seven jagged summits and 13,000 vertical feet of climbing. Who knew it could be so much fun? Join Tommy Caldwell and Alex Honnold on the inspiring – and at times hilarious – quest that earned the Piolet d’Or, mountaineering’s highest prize. HIGH and MIGHTY 20 mins High ball bouldering – where a fall could lead to serious injury – is not for the faint of heart. Add to the equation a level of difficulty at climbing’s cutting edge, and things can get downright out of control. Follow Daniel Woods’ epic battle to conquer fear and climb the high ball test piece The Process. SHOWDOWN at HORSESHOE HELL 20 mins 24 Hours of Horseshoe Hell is the wildest event in the climbing world; a mash-up of ultramarathon and Burning Man where elite climbers and gumbies alike go for broke in a sun-up to sun-down orgy of lactic acid and beer. But all fun aside, the competition is real: Can the team of Nik Berry and Mason Earle stand up Clockwise from top left: Alex Honnold at 24 Hours of Horseshoe Hell; adventure sport icon Dean Potter; against the all-powerful Alex Honnold? Kevin Jorgeson on the Dawn Wall in Yosemite; Tommy Caldwell on the Dawn Wall in Yosemite DEAN POTTER TRIBUTE DAWN WALL: FIRST LOOK 6 mins 15 mins Dean Potter was the most iconic vertical adventurer of a Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson’s epic final push to free climb generation. -

Presentation Title

April 17, 2020 Creating a Global Entertainment Content, Digital Media & OTT Powerhouse Disclaimer This communication contains “forward-looking statements” within the meaning of Section 27A of the Securities Act of 1933, as amended, or the Securities Act, and Section 21E of the Exchange Act, and such statements are subject to the safe harbors created thereby. Generally, these forward-looking statements can be identified by the use of forward-looking terminology such as “approximately,” “anticipate,” “believe,” “estimate,” “continue,” “could,” “expect,” “future,” “intend,” “may,” “plan,” “potential,” “predict,” “project,” “seek,” “should,” “will” and similar expressions. Those statements include, among other things, the discussions of Eros International’s business strategy and expectations concerning its and the combined company’s market position, future operations, margins, profitability, liquidity and capital resources, tax assessment orders and future capital expenditures. All such forward- looking statements are subject to risks and uncertainties that may cause actual results to differ materially from those that Eros International is expecting, including, without limitation: Eros International’s and the combined company’s ability to successfully and cost-effectively source film content; Eros International’s and the combined company’s ability to achieve the desired growth rate of Eros Now, its digital over-the-top (“OTT”) entertainment service; Eros International’s and the combined company’s ability to maintain or raise sufficient capital; -

MPLC Studioliste Juli21-2.Pdf

MPLC ist der weltweit grösste Lizenzgeber für öffentliche Vorführrechte im non-theatrical Bereich und in über 30 Länder tätig. Ihre Vorteile + Einfache und unkomplizierte Lizenzierung + Event, Title by Title und Umbrella Lizenzen möglich + Deckung sämtlicher Majors (Walt Disney, Universal, Warner Bros., Sony, FOX, Paramount und Miramax) + Benutzung aller legal erworbenen Medienträger erlaubt + Von Dokumentar- und Independent-, über Animationsfilmen bis hin zu Blockbustern ist alles gedeckt + Für sämtliche Vorführungen ausserhalb des Kinos Index MAJOR STUDIOS EDUCATION AND SPECIAL INTEREST TV STATIONS SWISS DISTRIBUTORS MPLC TBT RIGHTS FOR NON THEATRICAL USE (OPEN AIR SHOW WITH FEE – FOR DVD/BLURAY ONLY) WARNER BROS. FOX DISNEY UNIVERSAL PARAMOUNT PRAESENS FILM FILM & VIDEO PRODUCTION GEHRIG FILM GLOOR FILM HÄSELBARTH FILM SCHWEIZ KOTOR FILM LANG FILM PS FILM SCHWEIZER FERNSEHEN (SRF) MIRAMAX SCM HÄNSSLER FIRST HAND FILMS STUDIO 100 MEDIA VEGA FILM COCCINELLE FILM PLACEMENT ELITE FILM AG (ASCOT ELITE) CONSTANTIN FILM CINEWORX DCM FILM DISTRIBUTION (SCHWEIZ) CLAUSSEN+PUTZ FILMPRODUKTION Label Anglia Television Animal Planet Productions # Animalia Productions 101 Films Annapurna Productions 12 Yard Productions APC Kids SAS 123 Go Films Apnea Film Srl 20th Century Studios (f/k/a Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp.) Apollo Media Distribution Gmbh 2929 Entertainment Arbitrage 365 Flix International Archery Pictures Limited 41 Entertaiment LLC Arclight Films International 495 Productions ArenaFilm Pty. 4Licensing Corporation (fka 4Kids Entertainment) Arenico Productions GmbH Ascot Elite A Asmik Ace, Inc. A Really Happy Film (HK) Ltd. (fka Distribution Workshop) Astromech Records A&E Networks Productions Athena Abacus Media Rights Ltd. Atlantic 2000 Abbey Home Media Atlas Abot Hameiri August Entertainment About Premium Content SAS Avalon (KL Acquisitions) Abso Lutely Productions Avalon Distribution Ltd. -

Spring 2020 New RELEASES © 2020 Paramount Pictures 2020 © © 2020 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc

Spring 2020 New RELEASES © 2020 Paramount Pictures 2020 © © 2020 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. All Rights Reserved. © 2020 Universal City Studios Productions LLLP. © Lions Entertainment, Gate © Inc. © 2020 Disney Enterprises Inc. Bros. Ent. All rights reserved. © 2020 Warner swank.com/motorcoaches 10795 Watson Road 1.888.416.2572 St. Louis, MO 63127 MovieRATINGS GUIDE G/PG: Midway ............................. Page 19 Nightingale, The.............. Page 21 Peanut Butter Ode to Joy ........................ Page 18 Abominable .........................Page 7 Falcon, The ..........................Page 4 Official Secrets ................ Page 14 Addams Family, The ..........Page 5 Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark ................ Page 12 Once Upon a Time Angry Birds in Hollywood ......................Page 9 Movie 2, The .......................Page 4 Super Size Me 2: Holy Chicken ................... Page 15 One Child Nation ...............Page 9 Arctic Dogs .........................Page 7 Where'd You Go, Parasite ............................. Page 15 Beautiful Day in the Bernadette ..........................Page 6 Neighborhood, A ...............Page 3 Queen & Slim ................... Page 13 Dora and the Lost Rambo: Last Blood ............Page 9 City of Gold .........................Page 9 Report, The ...................... Page 14 Downton Abbey ............. Page 14 R: Terminator: Farewell, The ................... Page 12 21 Bridges ........................ Page 10 Dark Fate .............................Page 3 Frozen II ...............................Page