The Frankfurt School's Interest in Freud and the Impact of Eros And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thejudaic Element in the Teachings of the Frankfurt School

The Judaic Element in the Teachings of the Frankfurt School BY JUDITH MARCUS AND ZOLTAN TAR INTRODUCTION j In dealing with the question of the Judaic element in the teachings of the Frankfurt School, one does well to proceed as the Hebrew script does, that is, from right to left.* First, there should be a highly compressed account ofwhat on or publication of the Frankfurt School was about, and, second, an explanation ofwhat is meant by the teachings of the Frankfurt School, that is, the theoretical content of the School. Finally, we take up the main business at hand, that is, the examination of the Judaic element in the work of three Frankfurt School theorists: Max Horkheimer, Theodor Wiesengrund Adorno and Erich Fromm. Even in the case ofsuch a relatively modest and at times descriptive task as personal use only. Citati this has to be, a social scientist and historian of ideas is bound to refer to the rums. Nutzung nur für persönliche Zwecke. methodology applied. The approach will follow several lines of investigation, tten permission of the copyright holder. most notably that of the sociology of knowledge, i.e., the "existential determination of ideas" approach. If Hegel is right in saying that "to comprehend what is, is the task of philosophy [and] whatever happens, every individual is a child of his time; and philosophy is [but] its own time comprehended in thought",' then this is particularly true of the thinkers of the Frankfurt School. We might add to Hegel's dictum that each social philosophy is and remains limited and/or influenced by the historical conditions, and, subjectively, by the physical and mental constitution of its originator. -

Marxism in the Works of Erich Fromm and the Crisis of Socialism Enzo

Propriety of the Erich Fromm Document Center. For personal use only. Citation or publication of mate- rial prohibited without express written permission of the copyright holder. Eigentum des Erich Fromm Dokumentationszentrums. Nutzung nur für persönliche Zwecke. Veröffentli- chungen – auch von Teilen – bedürfen der schriftlichen Erlaubnis des Rechteinhabers. Marxism in the Works of Erich Fromm and the Crisis of Socialism Enzo Lio Paper presented as a first draft on the seminar of the International Erich Fromm Society on Charac- ter Structure and Society, Janus Pannonius University, Pécs/Hungary, August 24-26, 1990. - First published in the Yearbook of the International Erich Fromm Society, Vol. 2: Erich Fromm und die Kritische Theorie, Münster: LIT-Verlag, 1991, pp. 250-264. Copyright © 1991 and 2011 by Dr. Enzo Lio, Vicolo Quartirolo 5, I-40121 Bologna, Italy; E-Mail: en- zo.lio[at-symbol]@tele2.it. - Translation from Italian by Susan Garton, Bologna. 1. Introduction che is the product of the collective life history of humankind. This constitutes a scientifically valid The crisis of socialism, in the light of the histori- approach within the tradition of humanistic cal events that have provoked its downfall in thought insofar as, by using modern and effi- Eastern Europe, had already been discussed in cient scientific tools (psychoanalysis and the so- our Fromm Institute in Bologna, at the end of cial sciences) a closer and deeper investigation of 1989. Romano Biancoli maintained that Fromm the needs and motivations of human beings is had been proved right in his vision of Marxism possible. and of real socialism. I realized that, if Fromm The starting point for Fromm’s research is were still alive he would not be surprised by this precisely this, the search for the real and deep turn of events, which he hopes for in all his motives behind human action. -

NATURE, SOCIOLOGY, and the FRANKFURT SCHOOL by Ryan

NATURE, SOCIOLOGY, AND THE FRANKFURT SCHOOL By Ryan Gunderson A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Sociology – Doctor of Philosophy 2014 ABSTRACT NATURE, SOCIOLOGY, AND THE FRANKFURT SCHOOL By Ryan Gunderson Through a systematic analysis of the works of Max Horkheimer, Theodor W. Adorno, Herbert Marcuse, and Erich Fromm using historical methods, I document how early critical theory can conceptually and theoretically inform sociological examinations of human-nature relations. Currently, the first-generation Frankfurt School’s work is largely absent from and criticized in environmental sociology. I address this gap in the literature through a series of articles. One line of analysis establishes how the theories of Horkheimer, Adorno, and Marcuse are applicable to central topics and debates in environmental sociology. A second line of analysis examines how the Frankfurt School’s explanatory and normative theories of human- animal relations can inform sociological animal studies. The third line examines the place of nature in Fromm’s social psychology and sociology, focusing on his personality theory’s notion of “biophilia.” Dedicated to 바다. See you soon. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my dissertation committee immense gratitude for offering persistent intellectual and emotional support. Linda Kalof overflows with kindness and her gentle presence continually put my mind at ease. It was an honor to be the mentee of a distinguished scholar foundational to the formation of animal studies. Tom Dietz is the most cheerful person I have ever met and, as the first environmental sociologist to integrate ideas from critical theory with a bottomless knowledge of the environmental social sciences, his insights have been invaluable. -

Feminist Theory and the Frankfurt School: Introduction

wendy brown Feminist Theory and the Frankfurt School: Introduction Feminism is a revolt against decaying capitalism. —Marcuse There is a quaintness to Herbert Marcuse’s manifesto on behalf of “feminist socialism,” here reprinted for the first time since its appearance thirty years ago in Women’s Studies. It is not only an open- hearted and hopeful little effort at theoretically codifying the expansive revolutionary promise of the second wave of the Women’s Movement, a promise that would soon be dashed from within and without. Marcuse’s political and philosophical assumptions were also vulnerable to emerg- ing postfoundational critiques of the humanist subject, progressive his- toriography, and their entailments: essentialized identities, totalizing identities, undeconstructed binary oppositions, faith in emancipation, and revolution. Openhearted, hopeful, vulnerable, imaginative, revolution- ary: precisely the qualities Marcuse thought feminism brought to the unyielding and ultimately unemancipatory rationality of a masculinist radical politics, on the one hand, and a dreamless liberal egalitarianism, on the other. This unemancipatory rationality was the terrain that the Frankfurt School worked from every direction, as it upturned the myth of Volume 17, Number 1 doi 10.1215/10407391-2005-001 © 2006 by Brown University and d i f f e r e n c e s : A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/differences/article-pdf/17/1/1/405311/diff17-01_02BrownFpp.pdf by guest on 29 September 2021 Feminist Theory and the Frankfurt School Enlightenment reason, integrated psychoanalysis into political philosophy, pressed Nietzsche and Weber into Marx, attacked positivism as an ideology of capitalism, theorized the revolutionary potential of high art, plumbed the authoritarian ethos and structure of the nuclear family, mapped cultural and social effects of capital, thought and rethought dialectical materialism, and took philosophies of aesthetics, reason, and history to places they had never gone before. -

8. Erich Fromm's Social-Psychological

RUDOLF SIEBERT 8. ERICH FROMM’S SOCIAL-PSYCHOLOGICAL THEORY OF RELIGION Toward the X-Experience and the City of Being INTRODUCTION1 This essay explores Erich Fromm’s social-psychological theory of religion, as X- experience and longing for the City of Being, as being informed by the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament, Meister Eckhart as well as Georg W.F Hegel, Karl Marx, and Sigmund Freud. Its religious attitude constituted the very dynamic of Fromm’s writings, as well as of those of the other critical theorists of society, e.g. Max Horkheimer, Theodor W. Adorno, Walter Benjamin, Leo Loewenthal, Herbert Marcuse, etc., It united them. It could only be expressed in poetical symbols: the X-experience; or the longing for the imageless, nameless, notionless utterly Other than the horror and terror of nature and history; or the yearning for perfect justice and unconditional love: that the murderer may not triumph over the innocent victim, at least not ultimately. Man begins to become man only with the awakening of this longing for the entirely Other, or the X-experience. This religious attitude aims as idology at the destruction of all idolatry. In the Near East –––––––––––––– 1 Editors’ note-The author’s use of Fromm’s concept of “x-experience” comes from this passage in his work: What we call the religious attitude is an x that is expressible only in poetic and visual symbols. This x experience has been articulated in various concepts which have varied in accordance with the social organization of a particular cultural period. In the Near East, x was expressed in the concept of a supreme tribal chief, or king, and thus „God” became the supreme concept of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, which were rooted in the social structures of that area. -

A Paper to Be Presented at the 6Th European CHEIRON Meeting in Brighton^England, 2-6 September 1987. Research Was Funded

Propriety of the Erich Fromm Document Center. For personal use only. Citation or publication of material prohibited without express written permission of the copyright holder. Eigentum des Erich Fromm Dokumentationszentrums. Nutzung nur für persönliche Zwecke. Veröffentlichungen – auch von Teilen – bedürfen der schriftlichen Erlaubnis des Rechteinhabers. "INSTINCTS" AND THE "FORCES OF PRODUCTION": The Freud-Marx Debates in Eastern and Central Europe* Dr. Ferenc Eros Institute of Psychology, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest In his essay "Psychology and Art Today", the British-American poet Wystan Hugh Auden writes: Both Freud and Marx start from the failures of civiliza tion, one from the poof, one from the ill. Both see human behavior determined, not consciously, but by instinctive needs, hunger and love. Both desire a world where rational choice and self-determination are possible. The difference between them is the inev itable difference between the man who studies crowds in the street, and the man who sees the patient... in the consulting room- Marx sees the direction of the relations between the outer and inner world from without inwards. Freud vice-versa.... The socialist accuses the psychologist of caving in to the status quo, trying to adapt the neurotic to the system, thus depriving him of a potential revolutionary; the psychologist retorts that the socialist is trying to lift himself by his own boot tags, that he fails to understand himself or the fact that lust for money is only one form of the lust for power; and so that after he has won his power by revolution he will recreate the same conditions. -

Critical Theory of Herbert Marcuse: an Inquiry Into the Possibility of Human Happiness

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1986 Critical theory of Herbert Marcuse: An inquiry into the possibility of human happiness Michael W. Dahlem The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dahlem, Michael W., "Critical theory of Herbert Marcuse: An inquiry into the possibility of human happiness" (1986). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5620. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5620 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 This is an unpublished manuscript in which copyright sub s is t s, Any further reprinting of its contents must be approved BY THE AUTHOR, Mansfield Library U n iv e rs ity o f Montana Date :_____1. 9 g jS.__ THE CRITICAL THEORY OF HERBERT MARCUSE: AN INQUIRY INTO THE POSSIBILITY OF HUMAN HAPPINESS By Michael W. Dahlem B.A. Iowa State University, 1975 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Montana 1986 Approved by Chairman, Board of Examiners Date UMI Number: EP41084 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Cultural Marxism and Cultural Studies Douglas Kellner

Cultural Marxism and Cultural Studies Douglas Kellner (http://www.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/kellner/) Many different versions of cultural studies have emerged in the past decades. While during its dramatic period of global expansion in the 1980s and 1990s, cultural studies was often identified with the approach to culture and society developed by the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies in Birmingham, England, their sociological, materialist, and political approaches to culture had predecessors in a number of currents of cultural Marxism. Many 20th century Marxian theorists ranging from Georg Lukacs, Antonio Gramsci, Ernst Bloch, Walter Benjamin, and T.W. Adorno to Fredric Jameson and Terry Eagleton employed the Marxian theory to analyze cultural forms in relation to their production, their imbrications with society and history, and their impact and influences on audiences and social life. Traditions of cultural Marxism are thus important to the trajectory of cultural studies and to understanding its various types and forms in the present age. The Rise of Cultural Marxism Marx and Engels rarely wrote in much detail on the cultural phenomena that they tended to mention in passing. Marx’s notebooks have some references to the novels of Eugene Sue and popular media, the English and foreign press, and in his 1857-1858 “outline of political economy,” he refers to Homer’s work as expressing the infancy of the human species, as if cultural texts were importantly related to social and historical development. The economic base of society for Marx and Engels consisted of the forces and relations of production in which culture and ideology are constructed to help secure the dominance of ruling social groups. -

This Body, This Civilization, This Repression: an Inquiry Into Freud and Marcuse

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 2008 This body, this civilization, this repression: An inquiry into Freud and Marcuse Jeff Renaud University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Renaud, Jeff, "This body, this civilization, this repression: An inquiry into Freud and Marcuse" (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 8272. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/8272 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. THIS BODY, THIS CIVILIZATION, THIS REPRESSION: AN INQUIRY INTO FREUD AND MARCUSE by JeffRenaud A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through Philosophy in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements -

The Indispensability of Erich Fromm

The Indispensability of Erich Fromm: The Rehabilitation of a "Forgotten" Psychoanalyst Erich Fromm Lecture – International Psychoanalytic University Berlin, October 13, 2016 Peter L. Rudnytsky "Some human beings affect you so deeply that your life is forever changed." – Gérard D. Khoury, "A Crucial Encounter" "Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism, as I understand it. ... It is simply a question of which side one takes and what approach one follows." – George Orwell, "Why I Write" his unjustly tarnished reputation, whose dedi- 1 cated participants include Marco Bacciaga- luppi and Ferenc Erős and that owes every- It always begins for me with an act of reading. thing to Rainer Funk, Fromm’s literary execu- Winnicott’s Playing and Reality (1971), tor and supremely faithful custodian of his Ferenczi’s Clinical Diary (Dupont, 1985), legacy. Groddeck’s Book of the It (1923), Nina Col- tart’s "Slouching towards Bethlehem" (1986), The more I immersed myself in Fromm, the or – to go back to the beginning – Ernest more I was struck by how much my long- Jones’s (1953-1957) biography of Freud and, standing concerns have overlapped with his even before that, Norman O. Brown’s Life and how much I would have benefited had I Against Death (1959): all these have been, for heeded his writings sooner. Shortly before me, life-changing experiences, the most pas- beginning this odyssey, I had published an sionate love affairs in my lifelong romance essay (Rudnytsky, 2014) comparing Freud to with psychoanalysis. -

Theory, Totality, Critique: the Limits of the Frankfurt School Critical Theory, Marxism and Modernity

Studies in 20th Century Literature Volume 16 Issue 1 Special Issue on Contemporary Spanish Article 11 Poetry: 1939-1990 1-1-1992 Theory, Totality, Critique: The Limits of the Frankfurt School Critical Theory, Marxism and Modernity Philip Goldstein University of Delaware Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the German Literature Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Goldstein, Philip (1992) "Theory, Totality, Critique: The Limits of the Frankfurt School Critical Theory, Marxism and Modernity," Studies in 20th Century Literature: Vol. 16: Iss. 1, Article 11. https://doi.org/ 10.4148/2334-4415.1297 This Review Essay is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Theory, Totality, Critique: The Limits of the Frankfurt School Critical Theory, Marxism and Modernity Abstract Theory, Totality, Critique: The Limits of the Frankfurt School Critical Theory, Marxism and Modernity by Douglas Kellner. Keywords Frankfurt School, WWII, Critical Theory Marxism and Modernity, Post-modernism, society, theory, socio- historical perspective, Marxism, Marxist rhetoric, communism, communistic parties, totalization, totalizing approach This review essay is available in Studies in 20th Century Literature: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl/vol16/iss1/11 Goldstein: Theory, Totality, Critique: The Limits of the Frankfurt School Cr Review Essay Theory, Totality, Critique: The Limits of the Frankfurt School Philip Goldstein University of Delaware Douglas Kellner, Critical Theory, Marxism and Modernity. -

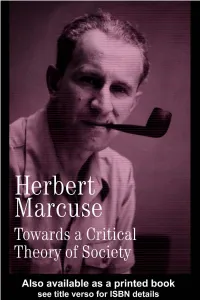

Towards a Critical Theory of Society Collected Papers of Herbert Marcuse Edited by Douglas Kellner

TOWARDS A CRITICAL THEORY OF SOCIETY COLLECTED PAPERS OF HERBERT MARCUSE EDITED BY DOUGLAS KELLNER Volume One TECHNOLOGY, WAR AND FASCISM Volume Two TOWARDS A CRITICAL THEORY OF SOCIETY Volume Three FOUNDATIONS OF THE NEW LEFT Volume Four ART AND LIBERATION Volume Five PHILOSOPHY, PSYCHOANALYSIS AND EMANCIPATION Volume Six MARXISM, REVOLUTION AND UTOPIA TOWARDS A CRITICAL THEORY OF SOCIETY HERBERT MARCUSE COLLECTED PAPERS OF HERBERT MARCUSE Volume Two Edited by Douglas Kellner London and New York First published 2001 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. © 2001 Peter Marcuse Selection and Editorial Matter © 2001 Douglas Kellner Afterword © Jürgen Habermas All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Marcuse, Herbert, 1898– Towards a critical theory of society / Herbert Marcuse; edited by Douglas Kellner. p. cm. – (Collected papers of Herbert Marcuse; v. 2) Includes bibliographical