A Collection of Short Stories Wei Xiong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plusinside Senti18 Cmufilmfest15

Pittsburgh Opera stages one of the great war horses 12 PLUSINSIDE SENTI 18 CMU FILM FEST 15 ‘BLOODLINE’ 23 WE-2 +=??B/<C(@ +,B?*(2.)??) & THURSDAY, MARCH 19, 2015 & WWW.POST-GAZETTE.COM Weekend Editor: Scott Mervis How to get listed in the Weekend Guide: Information should be sent to us two weeks prior to publication. [email protected] Send a press release, letter or flier that includes the type of event, date, address, time and phone num- Associate Editor: Karen Carlin ber of venue to: Weekend Guide, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 34 Blvd. of the Allies, Pittsburgh 15222. Or fax THE HOT LIST [email protected] to: 412-263-1313. Sorry, we can’t take listings by phone. Email: [email protected] If you cannot send your event two weeks before publication or have late material to submit, you can post Cover design by Dan Marsula your information directly to the Post-Gazette website at http://events.post-gazette.com. » 10 Music » 14 On the Stage » 15 On Film » 18 On the Table » 23 On the Tube Jeff Mattson of Dark Star City Theatre presents the Review of “Master Review of Senti; Munch Rob Owen reviews the new Orchestra gets on board for comedy “Oblivion” by Carly Builder,”opening CMU’s film goes to Circolo. Netflix drama “Bloodline.” the annual D-Jam show. Mensch. festival; festival schedule. ALL WEEKEND SUNDAY Baroque Coffee House Big Trace Johann Sebastian Bach used to spend his Friday evenings Trace Adkins, who has done many a gig opening for Toby at Zimmermann’s Coffee House in Leipzig, Germany, where he Keith, headlines the Palace Theatre in Greensburg Sunday. -

PLA 2021 Early Lit Calendar.Indd

JANUARY 2021 Daily literacy-building WWW.PLA.ORG activities to share with your child. SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 1 WRITING 2 PLAYING Draw the numbers 2021 and Play ‘Riddle Me.’ color them with your child. I’m white and cold and fun to Talk about the new year. play in. What am I? Yes! Snow! Take turns o ering riddles. 3 TALKING 4 SINGING 5 COUNTING 6 READING 7 WRITING 8 PLAYING 9 TALKING Have a conversation about Sing “The Rhyming Weigh your child and write Visit the library (or the With your child write Create a small obstacle Talk about colors. Ask your winter. Ask your child, “What Word” song. it here ______ . Save the library’s website if the (and talk about) course and give your child child what their favorite is your favorite thing about (Words are calendar and measure building is not open) and important dates directions. color is and share what your winter?” Tell what your on the back. ) again in June. check out a book. on a 2021 Go around the chair, go over the favorite color is. Talk about favorite thing is about winter. calendar. book, pick up the spoon, turn things that are those colors. around, and come back. 10 SINGING 11 COUNTING 12 READING 13 WRITING 14 PLAYING 15 TALKING 16 SINGING Pick a song your child is Measure your child’s height Use your finger to With your child write Play ‘Follow the Leader.’ Do Talk about food. Make up silly songs about familiar with and act it out and write it here ______ . -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 20/12/2018 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 20/12/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Perfect - Ed Sheeran Grandma Got Run Over By A Reindeer - Elmo & All I Want For Christmas Is You - Mariah Carey Summer Nights - Grease Crazy - Patsy Cline Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Feliz Navidad - José Feliciano Have Yourself A Merry Little Christmas - Michael Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Killing me Softly - The Fugees Don't Stop Believing - Journey Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Zombie - The Cranberries Baby, It's Cold Outside - Dean Martin Dancing Queen - ABBA Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Rockin' Around The Christmas Tree - Brenda Lee Girl Crush - Little Big Town Livin' On A Prayer - Bon Jovi White Christmas - Bing Crosby Piano Man - Billy Joel Jackson - Johnny Cash Jingle Bell Rock - Bobby Helms Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Baby It's Cold Outside - Idina Menzel Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Let It Go - Idina Menzel I Wanna Dance With Somebody - Whitney Houston Last Christmas - Wham! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! - Dean Martin You're A Mean One, Mr. Grinch - Thurl Ravenscroft Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Africa - Toto Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer - Alan Jackson Shallow - A Star is Born My Way - Frank Sinatra I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor The Christmas Song - Nat King Cole Wannabe - Spice Girls It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas - Dean Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Please Come Home For Christmas - The Eagles Wagon Wheel - -

270 Songs, 17.5 Hours, 1.62 GB Page 1 of 8 Name BPM Genre Rating

Page 1 of 8 WCS 270 songs, 17.5 hours, 1.62 GB Name BPM Genre Rating Artist Album Year Freezing 76 Pop Music Mozella Belle Isle (Deluxe… 2010 Thinking Out Loud 79 Pop Ballad Ed Sheeran x 2014 I'm So Miserable 83 Country Billy Ray Cyrus Some Gave All 1992 Too Darn Hot (RAC Mix) 83 R&B Ella Fitzgerald Verve Remixed: T… 2013 Feelin' Love 83 Blues Paula Cole City of Angels OST 1998 I'm Not the Only One 83 Pop Ballad Sam Smith In the Lonely Hou… 2014 Free 84 R&B Haley Reinhart Listen Up! 2012 Stompa 84 Alt Pop Serena Ryder Harmony 2012 Treat You Better 84 Pop Music Shawn Mendes Illuminate 2016 Heartbreak Road 85 Blues Rock Colin James Hearts on Fire 2015 Shape of My Heart 85 Rock Ballad Theory of a Deadman Shape of My Hear… 2017 Gold 86 Pop Music Kiiara low kii savage - EP 2015 I'm the Only One 87 Blues Rock Melissa Etheridge Yes I Am 1993 Rude Boy 87 Pop Music Rihanna Rated R 2009 Then 88 Pop Music Anne-Marie Speak Your Mind 2017 Can't Stay Alone Tonight 88 Pop-Rock Elton John The Diving Board… 2013 Vinyl (Remix) 88 Jazz-Pop Euge Groove feat. x-t.o.p. Sax S Euge Groove 2000 Wake Up Screaming 88 Country Gary Allan Used Heart For Sale 2000 Anything's Possible 88 R&B Jonny Lang Turn Around 2006 Slow Hands 88 Pop Music Niall Horan Slow Hands - Sin… 2017 Touch Of Heaven 88 Pop-Rock Richard Marx Flesh & Bone 1997 Forever Drunk 89 R&B Miss Li Beats & Bruises 2011 Let's Get Back To Bed Boy 89 R&B Sarah Connor Green Eyed Soul 2002 I Can't Stand the Rain 89 Pop-Soul Seal Soul 2008 Happy 90 R&B Ashanti Ashanti 2002 Mood For Luv 90 R&B B.B. -

Complete Libretto

MIRROR BUTTERFLY the migration liberation movement suite libretto & testimonials an Afro Yaqui Music Collective piece in collaboration with the CSA series at the New Hazlett Theatre MIRROR BUTTERFLY CONCEPT With its own roots in multiple nations “We asked, what are your stories? How and ethnicities, Pittsburgh’s Afro Yaqui would you like this to be told in a musical Music Collective seems uniquely tale?” Barson say. “And of course we do positioned to address the issue of a surrealist spin on it.” climate migration with art. The group mixes indigenous music from around Indigenous iconography informed the the world with jazz, hip-hop and funk. libretto, by acclaimed playwright Ruth Afro Yaqui is well known on the local Magraff, about the three heroines – a scene, but composer and baritone flower, a tree and a butterfly – who battle saxophonist says the group wanted to a sword character symbolizing take advantage of its residency with the capitalism, with its attendant extractive New Hazlett Theater’s Community industries and other forms of exploitation. Supported Art series to look at the big picture. Six dancers provide the movement, backed up by four choral singers and a “We wanted to step back and look at 15-piece band including saxophones, the forces that are going to be defining percussion, a rhythm section, and a our lives for the next 50 to 500 years,” string section that includes instruments he says. from China and Central Asia. The choreography is by nationally known The result is Mirror Butterfly: Migrant choreographer Peggy Choy, who blends Liberation Suite, a 50-minute opera East Asian traditional dance with African premiering this week. -

Lop40* with SHI\DOE STEVENS

ta1 ~~I~ (fa1 ~I *lOP40* WITH SHI\DOE STEVENS 1. HITS 'N' STABS :24 Hi, I'm Shadoe Stevens, inviting you to join me 'i,ere for the biggest hits on radios across the U.S.A. It's American Top 40: the biggest songs by 1he hottest stars, exclusive interviews, all the latest AT40 Music News ... an AT40 Flashback at t.its gon"' Jy... a Sneak" Peek at hits to come, Long Distance Dedications, and much more. So join me. i right i'are- for American Top 40! [LOCAL T.ll'l] . .. .. .. -. -- . / 1. NON-STOP CLIMB TO #1 l :26 Hi, Shadoe Stevens, AT40. Join me this welk.for a non-stop climb up the Billboard Chart to the #1 song in the U.S.A. We'll count down the top/son!Js on radio, music's hottest stars and their stories, all the latest Music News, our one-and-only AT40 Flashback, Sneak Peek songs, and Long Distance Dedications from listeners just like you -- it might even be you! It all happens right here and only here -- on American Top 40! [LOCAL YAG] 3575 Cahuenga Blvd W, Sutte 390, Los Angoles, CA 90068 • ABC Radio Networks IX Pill 1 VOICE: 213.850.1003 FAX: 213.874.7753 ;~. t 3575 Cahuenga Blvd W. Sun.e 390 AIR DATE WEEKEND: 01/28195 Los Angeles, CA 90068 SHOW#:JM HOURS: LU VOICE: 213.850.1003 . WITH Stl, E STEVENS FAX: 213.874.7753 ' ABC RADIO NETWORK and Opening Music, BMI Music, BMI #40 SHAME (B) Zhane HOLLY () Weezer #39 BASKET CASE. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

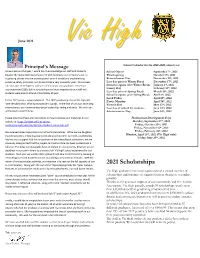

June-2021-Newsletter-1.Pdf

June 2021 Vic High Vic H igh School Calendar for the 2021-2022 school year Principal’s Message As we close out the year, I would like to acknowledge our staff and students. School Opens September 7th, 2021 Despite the many challenges that came with moving to our temporary site, re- Thanksgiving October 11th, 2021 organizing classes into the unanticipated ‘cohort’ model and implementing Remembrance Day November 11th, 2021 extensive safety protocols, our students had a very successful year. Our success Last day prior to Winter Break December 17th, 2021 th rate was one of the highest we have seen in years, our graduates earned an School re-opens after Winter Break January 4 , 2022 st unprecedented $350, 000 in scholarships and most importantly our staff and Family Day February 21 , 2022 Last day prior to Spring Break March 18th, 2022 students were able to attend school safely all year. School re-opens after Spring Break April 4th, 2022 th th Good Friday April 15 , 2022 To the 2021 grads – congratulations! The 145 graduating class of Vic High will Easter Monday April 18th, 2022 have the distinction of being our pandemic grads. In the face of unusual and trying Victoria Day May 23rd, 2022 circumstances you demonstrated great leadership, caring and poise. We wish you Last day of school for students June 23rd, 2022 all the best in your futures. Administrative Day June 24th, 2022 Please note that there are instructions on how to access your transcript on our Professional Development Days website at: https://vichigh.sd61.bc.ca/wp- Monday, September 27th, 2021 content/uploads/sites/26/2019/07/Student-Transcripts.pdf Friday, October 22nd, 2021 Friday, November 12th, 2021 th We received mixed news about our school’s renovations. -

Gypsum in California

TN 2.4 C3 A3 i<o3 HK STATE OP CAlIFOa!lTA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES msmtBmmmmmmmmmaam GYPSUM IN CALIFORNIA BULLETIN 163 1952 aou DIVl^ON OF MNES fZBar SDODSia sxh lasncisco ^"^^^^^nBM^^MMa^HBi«iaMa«NnMaMHBaaHB^HaHaa^^HHMi«nfl^HaMHiBHHHMauuHJin««aHiav^aMaHHaHHB«auKaiaMi^^M«ni^Maai^iMMWi^iM^ THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA DAVIS STATE OF CALIFORNIA EARL WARREN, Governor DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES WARREN T. HANNUM, Director DIVISION OF MINES FERRY BUILDING, SAN FRANCISCO 11 OLAF P. JENKINS, Chief San Francisco BULLETIN 163 September 1952 GYPSUM IN CALIFORNIA By WILLIAM E. VER PLANCK LIBRARY UNTXERollY OF CAUFC^NIA DAVIS LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL To IIlS EXCELLKNCY, TlIK IIONORAHLE EauL AVaRREN Governor of the State of California Dear Sir: I have the lionor to transmit herewitli liuUetiii 163, Gyj)- sinn in California, prepared under tlie direetion of Ohif P. Jenkins, Chief of the Division of ]\Iines. Gypsum represents one of the important non- metallic mineral commodities of California. It serves particularly two of California's most important industries, aprieulture and construction. In Bulletin 163 the author, W. p]. Xev Phinek, a member of the staff of the Division of Mines, has prepared a comprehensive treatise cover- ing all phases of the subject : history of the industry, geologic occurrence and origin of tlie minoi-al, mining, i)rocessing and marketing of the com- modity. Specific g3'psum i)roperties Avere examined and mapped. The report is profusely illustrated by maps, charts and photographs. In the preparation of the report it was necessary for the author to make field investigations, laboratory and library studies, and to determine how the mineral is used in industry as Avell as how it occurs in nature and how it is mined. -

Description, Narrative, and Reflection

EmpoWord: A Student-Centered Anthology & Handbook for College Writers Part One: Description, Narrative, and Reflection Author: Shane Abrams, Portland State University This chapter is licensed with a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License Download this book free at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/pdxopen/20/ Part One: Description, Narration, and Reflection 55 Section Introduction: Description, Narration, and Reflection Chapter Vocabulary Vocabulary Definition a rhetorical mode that emphasizes eye-catching, specific, and vivid description portrayal of a subject. Often integrates imagery and thick description to this end. a rhetorical mode involving the construction and relation of stories. narration Typically integrates description as a technique. a rhetorical gesture by which an author looks back, through the diegetic gap, to demonstrate knowledge or understanding gained from the subject on which they are reflecting. May also include consideration of reflection the impact of that past subject on the author’s future—“Looking back in order to look forward.” the circumstances in which rhetoric is produced, understood using the constituent elements of subject, occasion, audience, and purpose. Each element of the rhetorical situation carries assumptions and imperatives rhetorical situation about the kind of rhetoric that will be well received. Rhetorical situation will also influence mode and medium. Storytelling is one of few rituals that permeates all cultures. Indeed, there’s nothing quite as satisfying as a well-told story. But what exactly makes for a well-told story? Of course, the answer to that question depends on your rhetorical situation: your audience, your sociohistorical position, and your purpose will determine how you tell your story. -

Song & Music in the Movement

Transcript: Song & Music in the Movement A Conversation with Candie Carawan, Charles Cobb, Bettie Mae Fikes, Worth Long, Charles Neblett, and Hollis Watkins, September 19 – 20, 2017. Tuesday, September 19, 2017 Song_2017.09.19_01TASCAM Charlie Cobb: [00:41] So the recorders are on and the levels are okay. Okay. This is a fairly simple process here and informal. What I want to get, as you all know, is conversation about music and the Movement. And what I'm going to do—I'm not giving elaborate introductions. I'm going to go around the table and name who's here for the record, for the recorded record. Beyond that, I will depend on each one of you in your first, in this first round of comments to introduce yourselves however you wish. To the extent that I feel it necessary, I will prod you if I feel you've left something out that I think is important, which is one of the prerogatives of the moderator. [Laughs] Other than that, it's pretty loose going around the table—and this will be the order in which we'll also speak—Chuck Neblett, Hollis Watkins, Worth Long, Candie Carawan, Bettie Mae Fikes. I could say things like, from Carbondale, Illinois and Mississippi and Worth Long: Atlanta. Cobb: Durham, North Carolina. Tennessee and Alabama, I'm not gonna do all of that. You all can give whatever geographical description of yourself within the context of discussing the music. What I do want in this first round is, since all of you are important voices in terms of music and culture in the Movement—to talk about how you made your way to the Freedom Singers and freedom singing. -

![IF THIS IS a PROXY INTERVIEW (A009={2 Or 3}), GO to END of MODULE 8 [SELF- INTERVIEWS ONLY]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3299/if-this-is-a-proxy-interview-a009-2-or-3-go-to-end-of-module-8-self-interviews-only-763299.webp)

IF THIS IS a PROXY INTERVIEW (A009={2 Or 3}), GO to END of MODULE 8 [SELF- INTERVIEWS ONLY]

HRS 2018 -- MODULE 9: END OF LIFE DECISIONS FINAL VERSION -- 06/01/2018 ****************************************************************** NOTE ABOUT BRANCHPOINTS: Where there is more than one jump within a branchpoint box, the jumps are to be applied in order from the top. ****************************************************************** NOTE ABOUT COLORS AND MODE: All question text in black is for the core interview (except if CAPI and CAWI text is the same). Question text and codes in teal denotes CAWI (Web). The CAWI text will always be directly after the CAPI text. If wording is the same in both CAPI (Iwer Administered) and CAWI (Web), the text is black. Otherwise, black text for codeframes, interviewer instructions, jumps and branchpoints, etc., which can apply to both the CAPI and the CAWI interview unless specified otherwise or there is a CAWI alternative. On a black-and-white hard copy of the document, the TEAL text will appear somewhat lighter than the original black. ****************************************************************** NOTE ABOUT NON-RESPONSE FLOW: ANY QUESTION THAT IS ASKED BUT LEFT WITHOUT A RESPONSE IN CAWI INTERVIEWS WILL FOLLOW THE SAME PATH AS A REFUSAL FOR THAT QUESTION, UNLESS OTHERWISE SPECIFIED. ****************************************************************** MAJOR FLOW CONTROL, CONDITION AND FILL VARIABLES IF RANDOM X009 (1-10) = 9 IF THIS IS A PROXY INTERVIEW (A009={2 or 3}), GO TO END OF MODULE 8 [SELF- INTERVIEWS ONLY] V551 BRANCHPOINT: ASK IF X009 = 9 AND THIS IS A SELF INTERVIEW (A009 = 1), ELSE GO TO END OF MODULE Page 1 of 7 V551_PREFER Now we have some questions about health care treatments that you might want in certain situations and about how you would like health care decisions to be made.