Establishment of a Master Cycle Menu And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

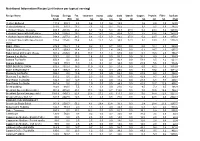

Nutritional Information Recipe List (Values Per Typical Serving)

Nutritional Information Recipe List (values per typical serving) Recipe Name Energy Energy Fat saturates mono poly Carb Starch Sugars Protein Fibre Sodium (kcal) (KJ) (g) (g) (g) (g) (g) (g) (g) (g) (g) (mg) (1 slice) Buttered 111.8 488.1 5.8 3.6 1.8 0.4 12.8 - 1.6 2.6 1.9 143.8 (2 slices) Buttered 223.6 976.1 11.7 7.1 3.6 0.7 25.5 - 3.2 5.2 3.9 287.5 4 chicken fingers - no sauce 493.3 2061.6 28.2 6.7 15.2 5.8 30.3 27.3 0.2 29.4 3.2 1219.6 4 chicken fingers with BBQ sauce 535.3 2236.9 28.3 6.7 15.2 5.8 40.4 27.3 7.5 29.4 3.4 1532.9 4 chicken fingers with plum sauce 544.8 2277.2 28.5 6.8 15.3 6.0 42.2 27.3 0.2 29.7 3.4 1370.2 4 chicken fingers with sweet & sour 515.4 2154.6 28.4 6.8 15.3 5.8 34.9 27.3 3.2 29.9 3.3 1316.8 sauce Bagel - Plain 272.9 1142.1 1.6 0.2 0.1 0.7 53.0 0.0 0.0 10.4 2.3 529.9 Bagel & cream cheese 470.7 1969.9 21.4 12.7 5.7 1.4 54.5 0.0 0.1 14.7 2.3 697.7 Bagel bacon and cream cheese 503.2 2105.8 24.6 13.7 7.1 1.8 54.5 0.0 0.1 15.5 2.3 756.7 Banana 4 oz Muffin 375.3 0.0 15.0 1.4 0.0 0.0 55.1 0.0 31.1 4.9 2.4 354.9 Banana 7oz Muffin 656.9 0.0 26.3 2.5 0.0 0.0 96.4 0.0 54.4 8.5 4.2 621.1 Banana Pudding 184.9 770.3 3.0 1.8 0.1 0.1 34.3 0.0 21.9 5.6 0.0 512.6 BEEF BOURGUIGNON 632.8 1932.4 36.0 11.9 10.8 0.8 27.8 0.0 6.5 40.2 1.9 1114.9 BEEF STROGANOFF 645.7 1806.9 38.8 13.8 10.2 0.9 29.0 0.0 7.3 39.2 2.3 1071.2 Blueberry 4oz Muffin 350.4 0.0 13.5 1.3 0.0 0.0 52.4 0.0 24.5 5.0 2.3 302.8 Blueberry 7 oz Muffin 613.2 0.0 23.6 2.3 0.0 0.0 91.7 0.0 42.9 8.7 4.0 529.9 Bran Raisin 4oz Muffin 332.3 0.0 12.7 1.1 0.0 0.0 48.2 0.0 24.3 -

Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday

You may order from the daily menu below or choose from our made-to-order options on page 3. Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday January 22 January 23 January 24 January 25 January 26 January 27 January 28 Breakfast: Omelet, Breakfast: French Breakfast: Egg Bake, Breakfast: Scrambled Breakfast: Biscuits & Breakfast: Egg & Breakfast: Cinnamon Roll, Toast, Scrambled or Scrambled Eggs, Eggs, Bacon, Boiled Gravy, Scrambled Cheese Biscuit, Scrambled Eggs, Scrambled Eggs, Boiled Eggs, Oat- Oatmeal, Yogurt Bar Egg, Yogurt Bar, Eggs, Yogurt Bar, Hashbrowns, Bacon, Bacon/Sausage, Oatmeal meal, Yogurt Bar Hashbrowns Boiled Egg, Oatmeal Scrambled Eggs, Oat- Toast meal, Yogurt Bar Week 3 Lunch: Shrimp, Ham Lunch: Chili, Turkey, Lunch: Red Pepper Lunch: Vegetable Beef Lunch: Cook’s Choice Lunch: Cheeseburger Lunch: Tuna Noodle Loaf, Apple Roast Beef, Chicken Gouda Soup, Glazed Soup, Hamburger Soup, Taco Salad, Chowder, Tilapia, Casserole, Maidrite Dumpling Finger Wrap Ham, Lasagna, Turkey Steak, Baked Chicken, Pizza Burger, Farmer’s Open Face Meatloaf Twist Sandwich Roast Beef/Swiss Delight Wrap Sandwich, Egg Salad Wrap Supper: Tuna & Supper: TaterTot Supper: Chicken and Supper: BBQ Pork/ Supper: Potato Soup, Supper: Hamburger Supper: Chili, Noodles, Jell-o Casserole Biscuits Bun Italian Beef/Bun Cinnamon Roll January 29 January 30 January 31 February 1 February 2 February 3 February 4 Breakfast: Omelet, Breakfast: French Breakfast: Egg Bake, Breakfast: Scrambled Breakfast: Biscuits & Breakfast: Egg & Breakfast: Cinnamon Roll, -

Chopsuey Cafe Presents a Collage of Fond Food Memories

CHOPSUEY CAFE PRESENTS A COLLAGE OF FOND FOOD MEMORIES INSPIRED BY THE MANY GOOD TIMES ABROAD SPENT IN CHINESE RESTAURANTS OR TAKEAWAYS SATIATING THE FOOD CRAVINGS OF A HUNGRY TRAVELLER / STUDENT. OUR MENU BRINGS TOGETHER FRESH PRODUCE, BOLD FLAVOURS, LUNCH TRADITIONAL PROFILES, INSPIRED COMBINATIONS, DECADENT DESSERTS AND REFRESHING COCKTAILS. DIM SUM * AVAILABLE ONLY FOR LUNCH & BRUNCH (V) VEGETARIAN CRYSTAL DUMPLINGS 4pcs 7 AUNTY MING'S DUMPLINGS 4pcs 12 FRIED PUMPKIN & PRAWN DUMPLINGS (V) SPICY MUSHROOM DUMPLINGS 4pcs 8 3pcs 9 CRISPY LOBSTER WANTONS 4pcs 15 TRADITIONAL HAR GAO 4pcs 9 CRISPY TINGLING PRAWN WANTONS 4pcs 12 WHITE SKIN SIEW MAI 4pcs 8 CHAR SIEW PAU 3pcs 9 STICKY RICE DUMPLINGS 3pcs 10 CHICKEN CHAR SIEW PAU 3pcs 9 SEARED PRAWN & SPINACH DUMPLINGS 3pcs 9 (V) VEGETARIAN CHAR SIEW PAU 3pcs 9 ORANGE DUCK DUMPLINGS 4pcs 9 FLAKEY CHAR SIEW PUFF 3pcs 9 SALADS STARTERS (VM) SEARED BEEF BUN CHA 25 (V) SPICY MUSHROOM SPRING ROLLS 16 rice noodles, mint, basil, lemongrass, peanuts, wok fried wild mushrooms fresh chilli & lime dressing PRAWN TOASTIES 16 king prawn paste, artisanal whitemeal, PAD THAI SALAD 24 black & white sesame seeds poached prawns, beancurd, chives, baby cos, bean sprouts, rice stick noodles, crushed peanuts, fresh lime CRISPY DUCK POW! POCKETS 17 shredded duck confit & pulled roasted duck, soft white buns, warmed sweet bean sauce GRILLED PORK SALAD 19 kale, red cabbage, crackling, tangy oriental dressing STICKY CRUNCHY BABY SQUID 16 wok crisped with tofu, peanuts, sticky sweet sauce (VM) DUCK & LYCHEE SALAD 19 -

HOP TUNG Chinese Vietnamese Restaurant

LUNCH SPECIALS SERVED UNTIL 3 PM Entrées are served with an egg roll, steamed, fried, or brown rice (add $1), 12-9:30 & your choice of hot and sour, egg drop, or wonton soup. NOTE: $1.00 is added to each lunch item on the weekend. SU CHICKEN 1. Sweet & Sour Chicken . .7.25 ,6. Lemongrass Chicken . 7.50 ,2. Curry Chicken . .7.50 ,7. Kung Pao Chicken . 7.50 3. Almond Chicken . .7.50 ,8. General Tso’s Chicken . 7.95 4.Chicken with Vegetables . .7.25 9. Sesame/, Orange Chicken . 7.95 12-10:30 12-10:30 ,5. Garlic Chicken . 7.50 ,10.Basil Chicken . 7.50 SA BEEF 11. Beef with Mushooms . 7.95 , 15. Mongolian Beef . 7.95 12.Beef with Vegetables . 7.25 16.Pepper Steak . 7.50 13.Beef with Broccoli . 7.25 ,17. Basil Beef . 7.50 ,14. 11-10:30 11-10:30 Curry Beef 7.50 F SHRIMP 18. Sweet & Sour Shrimp . 7.95 ,21. Kung Pao Shrimp with broccoli 8.95 19. Shrimp with Vegetables . 7.95 ,22. Curry Shrimp with Eggplant . 8.95 ,20.Lemongrass Shr. & Eggplant 8.95 ,23. Basil Shrimp . 8.95 11-9:30 COMBINATIONS 24. Triple Delight with Vegetables beef, chicken, & shrimp . 8.95 ,25. Hunan Chicken & Shrimp . 8.95 M-TH , 26. Sha Cha Triple Delight beef, chicken & shrimp . 8.95 , 27. Garlic Triple Delight shrimp, scallops, & chicken . 9.95 ,28. Black Bean Seafood Delight shrimp, scallops, squid, & imitation crab . 9.95 Only soup comes with the dishes below. OPEN | 200 | McAllen, TX 78504 Ste N. -

Senarai Kilang Dan Pembuat Makanan Yang Telah Mendapat Sijil Halal

SENARAI KILANG DAN PEMBUAT MAKANAN YANG TELAH MENDAPAT SIJIL HALAL DAERAH NO KILANG / PEMBUAT MAKANAN Belait 1. Ferre Cake House Block 4B, 100:5 Kompleks Perindusterian Jalan Setia Diraja, Kuala Belait. Negara Brunei Darussalam No Senarai 1 ponge Cake 2 ed Bean B skuit 3 ed Bean Mini Bun 4 utter Mini Bun 5 uger Bun 6 ot Dog Bun 7 ta Bread 8 offee Meal Bread 9 andwich Loaf 10 Keropok Lekor 11 urry Puff Pastry 12 Curry Puff Filling 13 onut 14 oty B oy/ R oti Boy 15 Noty Boy/ Roti Boy Topping 16 eropok Lekor kering 17 os K eropok Lekor 18 heese Bun Jumlah Produk : 18 2. Perusahaan Shida Dan Keluarga Block 4, B2 Light Industry, Kuala Belait KA 1931 Negara Brunei Darussalam No Senarai 1 Mee Kuning 2 Kolo Mee 3 Kuew Tiau 4 Tauhu Jumlah Produk : 4 Hak Milik Bahagian Kawalan Makanan Halal, Jabatan Hal Ehwal Syariah, Kementerian Hal Ehwal Ugama, Negara Brunei Darussalam 26 August, 2014 Page 1 of 47 DAERAH NO KILANG / PEMBUAT MAKANAN 3. Syarikat Hajah Saibah Haji Hassan Dan Anak-Anak Block 4 No B6 Kompleks Perindustrian Pekan Belait,Kuala Belait Negara Brunei Darussalam No Senarai 1 Mee Kuning 2 Kuew Teow 3 Kolo Mee Jumlah Produk : 3 4. Syarikat Hajah Saibah Haji Hassan Dan Anak-Anak Block 4B No 6 Tingkat Bawah,Kompleks Perindustrian Pekan Belait,Kuala Belait, Negara Brunei Darussalam No Senarai 1 Karipap Ayam 2 Karipap Daging 3 Karipap Sayur 4 Popia Ayam 5 Popia Daging 6 Popia Sayur 7 Samosa Ayam 8 Samosa Daging 9 Samosa Sayur 10 Onde Onde 11 Pulut Panggang Udang 12 Pulut Panggang Daging 13 Kelupis Kosong Jumlah Produk : 13 Brunei-Muara Hak Milik Bahagian Kawalan Makanan Halal, Jabatan Hal Ehwal Syariah, Kementerian Hal Ehwal Ugama, Negara Brunei Darussalam 26 August, 2014 Page 2 of 47 DAERAH NO KILANG / PEMBUAT MAKANAN 1. -

Springfield Menu

Dine In Carry Out Delivery Cater 204 Baltimore Pike Springfield, PA 19064 Phone : 610-544-3934 Email : [email protected] WWW.PHOSTREET.COM Hours Sunday - Thursday 11 AM - 9:00 PM Friday - Saturday 11 AM - 9:30 PM BYOB 1 - Crispy Spring Rolls 5 - Shrimp Summer Rolls 8 - Sampler Appetizer 9 - Wonton Soup 10 - Curry Chicken 11 - Duck Salad 13 - Sizzling Vietnamese Crepe 14 - Tempura Shrimp 71 - Vietnam Special Broken Rice 77 - Grilled Chicken Broken Rice 78 - Grilled Steak Broken Rice 31 - Deluxe Rice Noodle Soup 35 - Eye Round Steak & Beef 38 - Chicken Rice Noodle Soup 62 - Lemongrass Beef over Rice Meatballs Rice Noodle Soup 65 - Vegetarian Rice 53 - Seafood Rice Noodle Soup 58 - Spicy Beef Rice Noodle Soup 82 - Braised Shrimp 83 - Sweet & Sour Shrimp Soup 91 - Special Rice Vermicelli 95 - Grilled Shrimp & Pork Rice 98 - Grilled Chicken & Pork Rice 125 - Grilled Pork Hoagie Vermicelli Vermicelli Starters - Khai Vi 1. Crispy Spring Rolls - Cha Gio 4.49 Marinated ground pork, shrimp, clear vermicelli, yellow onions, carrots, and taro hand-rolled into crispy spring rolls; served with our house special savory sweet sauce, green leaf lettuce, mint, cilantro, and pickled carrots. 2. Summer Rolls - Goi Cuon 4.49 Shrimp, pork, rice vermicelli, green leaf lettuce, lettuce, bean sprout, mint, Chinese chives, and cilantro hand-rolled in rice paper; served with our signature peanut sauce. 3. Grilled Pork and Shrimp Summer Rolls - Goi Cuon Thit Nuong Tom 4.75 Grilled seasoned pork, shrimp, rice vermicelli, green leaf lettuce, lettuce, bean sprout, mint, Chinese chives, and cilantro hand-rolled in rice paper; served with our signature peanut sauce. -

Lunch Special SOUP Enjoy a Cup Or a Large Bowl of Rich & Marvelous Soup

Lunch Special SOUP Enjoy a cup or a large bowl of rich & marvelous soup. Cup: 3.50 Large bowl: 7.50 L1. Corn Egg Drop Soup Chicken broth with carrot, corn and green onion. L2. Wonton Soup Savory broth with home made pork wonton and green onion. L3. Hot and Sour Soup Tangy & rich broth with pork, bamboo shoots, mushrooms and egg. Chef’s Recommendation 10.95 L4. Hot Pepper Combination Delight L8. Peanut Butter Chicken L5. General’s Tso Chicken L9. Sesame Chicken L6. Amazing Terrace Chicken L10. Double Happiness L7. Amazing Jumbo Shrimp L11. Combination Delights Chicken 8.95 Beef (Flank steak) 9.95 L12. Sweet and Sour Chicken L26. Mongolian Beef L13. Almond Chicken L27. Hunan Beef L14. Cashew Chicken L28. Pepper Beef L15. Kung Pao Chicken L29. Kung Pao Beef L16. Broccoli Chicken L30. Broccoli Beef L17. Mix Veg with Chicken L31. Snow Peas with Beef L18. Chicken w/Hot Garlic Sauce L32. Beef w/Hot Garlic Sauce L19. Mongolian Chicken L33. Sichuan Beef L20. Lemon Grass Chicken L34. Lemon Grass Beef Pork 8.95 Tofu 9.95 L21. Sweet and Sour Pork L35. Peanut Butter Tofu L22. Sichuan Pork L36. Hot Pot Tofu L23. Hunan Pork L37. Mix Veg with Tofu L24. Mongolian Pork L38. Hunan Tofu L25. Pork w/Hot Garlic Sauce L39. Tofu w/Hot Garlic Sauce L40. Pan Asian Terrace Fried Rice Wok in savory soy sauce with egg, peas, carrots and green onion. Chicken/Beef/Pork/Vegetables 8.95 Jumbo Shrimp/Combination 10.95 L41. Pad Thai Pan fried rice noodles with green onions, bean sprouts, egg topped with crushed peanuts. -

Split Chicken Breast with Rib St. Louis Style Spare Ribs Eckrich Meat Franks

Colon_Decatur_VilMkt_062821_PG1 YOUR HOMETOWN STORE 2021: AD EFFECTIVE DATES MON. TUES. WED. THUR. FRI. SAT. SUN. JUNE JUNE JUNE JULY JULY JULY JULY 28 29 30 1 2 3 4 We are not providing rain checks due to supply We reserve the right to limit quantities. and demand from the Coronavirus (Covid-19). Whole Extra Large Seedless Dark Red 88 Watermelon 68 Cherries ....................................... $2 lb. each ........................ $3 Select Varieties Eckrich Split Chicken Village Market, All-Natural Meat Franks Breast with St. Louis Style 12 - 13 oz. BUY 2, GET 3 Rib Spare Ribs Eckrich Value Pack OF EQUAL OR Thick Cut or LESSER VALUE Regular Bologna or Cotto Salami 99 10 - 12 oz. � $3 lb. FREE! 99| 99lb. Select Varieties Kingsford Aunt Millie’s Select Varieties Homestyle or Charcoal Briquets Bush’s Best Stadium Buns Original (16 lb.) Baked Beans 8 ct. Match Light (12 lb.) 22 - 28 oz. BUY ONE, GET ONE FREE! $799 $188 Save at least $3.39 on 2 Save at least $4.00 on 1 Save at least 81� on 1 Select Varieties Our Family Select Varieties Select Varieties Party Size 7-Up Cheez-It Products Crackers Ice Cream 12 pk., 12 oz. cans 7.5 - 12.4 oz. gallon (plus deposit) BUY ONE, GET ONE $499 3/$999 FREE! Save at least $1.50 on 1 Save at least $7.98 on 3 Save at least $4.59 on 2 Select Varieties Select Varieties Lay’s Pepsi Potato Chips (7.5 - 8.75 oz.) or Products Poppables (5 oz.) 6 pk., 16.9 oz. btls. -

2/$4 2/$11 2/$5 10/$10 99¢ 4/$5 4/$9 5/$3 5/$10 $5.99 $3.39

Come in and get your FREE Pumps Perks Card! “Your family owned Save On Gas! and operated store” Phone: 218-435-1454 Store Hours FOODS & DELI 8am -8pm Mon-Sat 9am-4pm Sunday Fosston, Minnesota Double Coupon Sunday Sale Dates: Monday afternoon May 11 to May 17 through Wednesday SHARP CHEDDAR, MILD CHEDDAR OR MOZZARELLA - REG SHRED; COLBY JACK TOASTED OATS ULTRA PLUSH VAN CAMP’S OR MILD CHEDDAR - FINE SHRED OR RAISIN BRAN KRAFT QUILTED NORTHERN PORK’N SHREDDED CHEESE ESSENTIAL BEANS EVERYDAY BATH 4/$9 CEREAL TISSUE 5/$3 8 OZ 15 OZ 1 LB QUARTERED STROGANOFF, THREE CHEESE OR ESSENTIAL EVERYDAY 5/$10 $3.39 CHEDDAR CHEESE MELT 12-20 OZ 6 PK - DOUBLE ROLL HAMBURGER OR CASS CLAY BUTTER HELPER SMUCKERS KLEENEX GRAPE JELLY................. 32 OZ $1.89 WHITE FACIAL TISSUE ....... 160 CT 4/$5 10/$10 2/$5 4.7-6 OZ ASSORTED ALL PURPOSE ASSORTED 20 PACK CALIFORNIA PIZZA HUNT’S KITCHEN OR DI GIORNO PILLSBURY PEPSI COLA KETCHUP PIZZA FLOUR PRODUCTS 99¢ 2/$11 24 OZ 99¢ $5.99 CRANBERRY POMEGRANATE REGULAR OR PLUS CALCIUM 5 LBS BLUEBERRY PLUS CASS CLAY 12 OZ CANS LANGER’S ORANGE JUICE JUICE ESSENTIAL EVERYDAY AQUAFINA 2/$4 SUGAR ........................ 4 LBS $1.99 WATER..........24 PK - 1/2 LITER BTLS $4.39 4/$5 1/2 GAL 64 OZ FAMILY PACK 85% LEAN PORK FAMILY PACK BONE-IN FAMILY FAVORITE BONELESS SKINLESS BEEF BOLOGNA OR BEEF COTTO SALAMI GROUND BEEF ............. LB $3.99 PORK CHOPS ............... LB $1.99 CHICKEN BREASTS.... 2.5 LB BAG $4.99 OSCAR MAYER........... -

Appetizers Lighter Fare Specialty Salads Sides BBQ Sandwiches

Appetizers BBQ Sandwich es Buffalo Chicken Wings 9.69 & Burgers “Boneless” Buffalo Wings 8.69 ALL of our BBQ Sandwiches and Burgers Pork “Hawg” Wings (1/2 dozen) 9.99 are made with the freshest ingredients Above items available with our own and served with fries and a pickle. Teriyaki, Honey Garlic, Zesty BBQ, BBQ, Spicy Hickory BBQ, Garlic Parmesan, ......... ® Mild, Medium or Hot Sauces. Pulled Pork Sandwich ONEONT A | NY Served with celery & bleu cheese. Slow roasted “Brooks’ Style” Pulled Pork Since 1951 Pulled Pork Fries 8.99 with Brooks’ Original BBQ Sauce. 7.39 Chicken Tenders 7.69 Pork Bun Mozzarella Sticks 5.99 Sliced Roast Pork with Brooks’ Original BBQ Sauce. 6.69 Soup or Chowder of the Day Cup 2.99 Bowl 3.99 Beef Bun Sliced Choice Western Beef with Chicken Chili Brooks’ Original BBQ Sauce. 6.69 Choice of Red or White chili. Cup 2.99 Bowl 3.99 Chicken Spiedie Cut up chicken breast marinated in Lighter Fare our own Spiedie Marinade, grilled and served on a buttered roll. 7.69 “Founded in 1951, we’re Cup of Soup & Half Sandwich Grilled Chicken Breast still proud to call Choice of chowder or soup of the day Sandwich Oneonta, New York home. with one half: beef, BLT, ham & cheese, Grilled chicken breast, lightly seasoned We welcome you to grilled ham & cheese, grilled cheese, with our own Grillin’ Rub, topped turkey & swiss, chicken salad, tuna salad with crisp lettuce and tomato Brooks’ House of B BQ.” or egg salad sandwich . 6.89 and served with honey Dijon mustard on the side. -

Insidenside US Bank Locations Will Be Closed Sports Looking Back Classifieds Thursday, but Open Friday

Kuna man critically Homedale football coach injured in U.S. 95 crash tenders resignation Students’ turkey recipes PPageage 55AA PPagesages 116A6A B Section Wednesday, November 22, 2006 Established 1865 VOLUME 22, NUMBER 47 HOMEDALE, OWYHEE COUNTY, IDAHO SEVENTY-FIVE CENTS County’s Agency ready to Triangle fi le grant request Road for Homedale ruling With a little help from Sage grant — the maximum available — Community Resources, the City to install sidewalk, curbs, gutters of Homedale is ready to take a and do other improvements around appealed major step in sprucing up the main the parcels where a restaurant entrance to town. and motel are planned as well An Oreana area resident has The fi nal details of an Idaho as the commercial development appealed the Owyhee County Community Development Block across U.S. Highway 95 near the commissioners’ decision to make Grant application were hammered airport. Triangle Road public. out at a Friday morning meeting The grant application must Don Barnhill, the trustee for at City Hall. Representatives be submitted by Dec. 18, and Wintercamp Ranch, filed the from the city, Sage, the Idaho Labor and Commerce staff will appeal in district court on Nov. 7. Car crimes plague Homedale Department of Commerce and then consider recommending the In an Oct. 10 document signed “I think it must have been a kid,” Ida Burt said, dumbfounded as to Labor, the U.S. Department of project to the Idaho Economic by Hal Tolmie and Dick Reynolds, why her residence was selected as part of the a recent rash of vehicle Agriculture and the Homedale Advisory Council. -

The Official Publication of the Belted Galloway Society, Inc

www.beltie.org April 2015 US Beltie News THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE BELTED GALLOWAY SOCIETY, INC. © Leanne Musselman Fogle President Michelle Ogle England Galloway Group has been very busy in planning a spectacular event in honor of the twenty-fifth anniversary for Spring is finally here! Well--at least the calen- the sale. A preview of the animals offered is included in this dar says it has arrived. We have experienced newsletter. more snow and cooler-than-normal tempera- The first Northeast Regional Junior National for our youth tures for this time of year, so I am hoping the weather begins members will also be held. Please check out the information to agree with the calendar very soon. One definite sign that here and on beltie.org for more information about the event. spring is still on schedule is the spring calves. Over three- As we progress through calving season, the time for breed- quarters of our Belted Galloway herd has calved, and so far, ing will soon be upon us. Remember to have your bulls’ fer- no assistance has been need- tility checked, research bulls for ed. I am always in awe when sale, and invest in semen for an AI I witness how our breed can program. Herd health is especially have a calf up, cleaned and important at this time of year. Be- nursed so quickly. fore cattle go out on green pasture, Spring also brings one of it is a perfect time to vaccinate, my favorite events. This year worm, and evaluate your herd for I will be attending the Na- future sales and replacements.