Variation in Persian Vowel Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Kurmanji Kurdish As

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Kurmanji Kurdish as Spoken in Turkey 1. Special handling of dialects Kurmanji Kurdish is a major branch of modern Kurdish, which belongs to the Iranian group of languages. Kurdish is largely a spoken language with a limited but growing body of modern literature. There are many dialectal varieties of Kurdish spread over a wide area of Turkey, Iraq, Syria, Iran, Armenia and Azerbaijan. There are, in addition, different classifications of Kurdish languages and Kurdish peoples that align dialectal choice with tribal affinity. Linguistic and Kurdish scholars usually describe modern Kurdish as having two closely related major branches: Kurmanji (the northern branch) and Sorani (the southern branch). They are not mutually intelligible (see Thackston (2006) p. vii). The Kurdish Institute summarizes the situation as follows: “Kurdish has two regional standards, namely Kurmanji in Turkey, and Sorani farther east and south. Roughly half of Kurdish speakers live in Turkey.” (see http://www.institutkurde.org/en/ and also http://www.blueglobetranslations.com/about- kurdish-kurmanji-language.html). Within the larger region there are two other languages often associated with ethnic Kurds. These are Dimili (also known as Zazaki) and Gorani. Although sometimes classified as sub-dialects of Kurdish (e.g., Kurdish Language - Britannica Online Encyclopedia), these languages belong to a different group of Iranian languages (see for example, http://kurds_history.enacademic.com/346/Kurmanji). Although Kurmanji Kurdish is spoken across a range of countries, it has the advantage of being spoken by around 60-80% of Kurds and is considered a regional standard. The majority of Kurmanji speakers live in Turkey, making it the ideal country for collection of audio data (see for example, http://linguakurd.blogfa.com/post-106.aspx). -

Tajiki Some Useful Phrases in Tajiki Five Reasons Why You Should Ассалому Алейкум

TAJIKI SOME USEFUL PHRASES IN TAJIKI FIVE REASONS WHY YOU SHOULD ассалому алейкум. LEARN MORE ABOUT TAJIKIS AND [ˌasːaˈlɔmu aˈlɛɪkum] /asah-lomu ah-lay-koom./ THEIR LANGUAGE Hello! 1. Tajiki is spoken as a first or second language by over 8 million people worldwide, but the Hоми шумо? highest population of speakers is located in [ˈnɔmi ʃuˈmɔ] Tajikistan, with significant populations in other /No-mee shoo-moh?/ Central Eurasian countries such as Afghanistan, What is your name? Uzbekistan, and Russia. Номи ман… 2. Tajiki is a member of the Western Iranian branch [ˈnɔmi man …] of the Indo-Iranian languages, and shares many structural similarities to other Persian languages /No-mee man.../ such as Dari and Farsi. My name is… 3. Few people in America can speak or use the Tajiki Шумо чи xeл? Нағз, рахмат. version of Persian. Given the different script and [ʃuˈmɔ ʧi χɛl naʁz ɾaχˈmat] dialectal differences, simply knowing Farsi is not /shoo-moh-chee-khel? Naghz, rah-mat./ enough to fully understand Tajiki. Those who How are you? I’m fine, thank you. study Tajiki can find careers in a variety of fields including translation and interpreting, consulting, Aз вохуриамон шод ҳастам. and foreign service and intelligence. NGOs [az vɔχuˈɾiamɔn ʃɔd χaˈstam] and other enterprises that deal with Tajikistan /Az vo-khu-ri-amon shod has-tam./ desperately need specialists who speak Tajiki. Nice to meet you. 4. The Pamir Mountains which have an elevation Лутфан. / Рахмат. of 23,000 feet are known locally as the “Roof of [lutˈfan] / [ɾaχˈmat] the World”. Mountains make up more than 90 /Loot-fan./ /Rah-mat./ percent of Tajikistan’s territory. -

Judeo-Persian Literature Chapter Author(S): Vera Basch Moreen Book

Princeton University Press Chapter Title: Judeo-Persian Literature Chapter Author(s): Vera Basch Moreen Book Title: A History of Jewish-Muslim Relations Book Subtitle: From the Origins to the Present Day Book Editor(s): Abdelwahab Meddeb, Benjamin Stora Published by: Princeton University Press. (2013) Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt3fgz64.80 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Princeton University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to A History of Jewish-Muslim Relations This content downloaded from 89.176.194.108 on Sun, 12 Apr 2020 13:51:06 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Judeo- Persian Literature Vera Basch Moreen Jews have lived in Iran for almost three millennia and became profoundly acculturated to many aspects of Iranian life. This phenomenon is particu- larly manifest in the literary sphere, defi ned here broadly to include belles lettres, as well as nonbelletristic (i.e., historical, philosophical, and polemi- cal) writings. Although Iranian Jews spoke Vera Basch Moreen many local dialects and some peculiar Jewish dialects, such as the hybrid lo- Vera Basch Moreen is an independent Torah[i] (Heb. + Pers. -

The Socio Linguistic Situation and Language Policy of the Autonomous Region of Mountainous Badakhshan: the Case of the Tajik Language*

THE SOCIO LINGUISTIC SITUATION AND LANGUAGE POLICY OF THE AUTONOMOUS REGION OF MOUNTAINOUS BADAKHSHAN: THE CASE OF THE TAJIK LANGUAGE* Leila Dodykhudoeva Institute Of Linguistics, Russian Academy Of Sciences The paper deals with the problem of closely related languages of the Eastern and Western Iranian origin that coexist in a close neighbourhood in a rather compact area of one region of Republic Tajikistan. These are a group of "minor" Pamir languages and state language of Tajikistan - Tajik. The population of the Autonomous Region of Mountainous Badakhshan speaks different Pamir languages. They are: Shughni, Rushani, Khufi, Bartangi, Roshorvi, Sariqoli; Yazghulami; Wakhi; Ishkashimi. These languages have no script and written tradition and are used only as spoken languages in the region. The status of these languages and many other local linguemes is still discussed in Iranology. Nearly all Pamir languages to a certain extent can be called "endangered". Some of these languages, like Yazghulami, Roshorvi, Ishkashimi are included into "The Red Book " (UNESCO 1995) as "endangered". Some of them are extinct. Information on other idioms up to now is not available. These languages live in close cooperation and interaction with the state language of Tajikistan - Tajik. Almost all population of Badakhshan is multilingual or bilingual. The second language is official language of the state - Tajik. This language is used in Badakhshan as the language of education, press, media, and culture. This is the reason why this paper is focused on the status of Tajik language in Republic Tajikistan and particularly in Badakhshan. The Tajik literary language (its oral and written forms) has a long history and rich written traditions. -

1 Allomorphy in Gilaki

Allomorphy in Gilaki: an Optimality Theoretic approach Gregory Antono JAL401, University of Toronto Allomorphy appears to be a common occurrence in Gilaki, where there are stem changes as a result of affixation or verbal inflection, and various forms for certain affixes. Through an analysis based on the Optimality Theory (OT) framework (Prince and Smolensky 2004), this study seeks to examine the phonological constraints and constraint ranking involved in Gilaki allomorphy, focusing on the phonologically-conditioned allomorphs of the plural morpheme -ʃɑn and the negative affix –nV-. The plural morpheme -ʃɑn can surface as several forms like -ɑn and –jɑn: (1) tup-ɔ-ʃanə (2) tup-ɑn ball-ɔ-PL ball-PL balls balls (3) kor-ɑn (4) putʃɑ-jɑn girl-PL cat-PL girls cats The negative bound morpheme, –nV-, surfaces with varying vowels, such as nɔ-, nɪ-, or neɪ-. (5) nɔ-dʊvas-əm/ (6) mo nɪʃkæstʌm NEG.run.1SG 1.SG break.NEG did not run I did not break (7) mo neɪmijaɾʌm/ (8) nɔ-ʃɔn-ɔm/ 1.S NEG.die.1SG NEG.go.1SG I did not die not go An Optimality Theoretic approach to allomorphy has been taken by many, such as Rubach and Booij (2001) on Polish iotation, Anderson on phonologically conditioned allomorphy in Surmiran (2008), and Udammadu (2017) on the Igbo language. For this study, translation tasks are carried out with the Gilaki consultant to elicit more plural and negation data, using various simple storyboards that contain singular and plural subjects (animals), as well as dialogue that would elicit the negation affix. The focus of this elicitation is to observe how the affixes vary depending on the stem. -

A Corpus Phonetic Study of Contemporary Persian Vowels in Casual Speech

University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 25 Issue 1 Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Penn Article 15 Linguistics Conference 2-27-2019 A Corpus Phonetic Study of Contemporary Persian Vowels in Casual Speech Taylor Jones University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl Recommended Citation Jones, Taylor (2019) "A Corpus Phonetic Study of Contemporary Persian Vowels in Casual Speech," University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: Vol. 25 : Iss. 1 , Article 15. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol25/iss1/15 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol25/iss1/15 For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Corpus Phonetic Study of Contemporary Persian Vowels in Casual Speech Abstract Contemporary Iranian Persian is described as having a six vowel system; however, there is currently very little work that characterizes the exact nature of these vowels. Previous works posit substantially different vowel spaces, and conflicting accounts of the extent ot which historical length distinctions are still relevant in Persian -- these distinctions then affect phonological theorizing, especially with regards to vocalic assimilation (sometimes referred to as "vowel harmony"). This study uses a corpus of over 60 hours of casual telephone speech among 104 speakers to describe the vowels of Persian. It is demonstrated that historical length distinctions no longer obtain, that previous descriptions of the vowel space of Persian are no longer necessarily accurate, and that the low back vowel may no longer be a steady state vowel for all speakers nor as low or as rounded as previously described. -

A Linguistic Conversion Mīrzā Muḥammad Ḥasan Qatīl and the Varieties of Persian (Ca

Borders Itineraries on the Edges of Iran edited by Stefano Pellò A Linguistic Conversion Mīrzā Muḥammad Ḥasan Qatīl and the Varieties of Persian (ca. 1790) Stefano Pellò (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia) Abstract The paper deals with Mīrzā Muḥammad Ḥasan Qatīl, an important Persian-writing Khatri poet and intellectual active in Lucknow between the end of the 18th and the first two decades of the 19th century, focusing on his ideas regarding the linguistic geography of Persian. Qatīl dealt with the geographical varieties of Persian mainly in two texts, namely the Shajarat al-amānī and the Nahr al- faṣāḥat, but relevant observations are scattered in almost all of his works, including the doxographic Haft tamāshā. The analysis provided here, which is also the first systematic study on a particularly meaningful part of Qatīl’s socio-linguistic thought and one of the very few explorations of Qatīl’s work altogether, not only examines in detail his grammatical and rhetorical treatises, reading them on the vast background of Arabic-Persian philology, but discusses as well the interaction of Qatīl’s early conversion to Shi‘ite Islam with the author’s linguistic ideas, in a philological-historical perspective. Summary 1. Qatīl’s writings and the Persian language question. –2. Defining Persian in and around the Shajarat al-amānī. –3. Layered hegemonies in the Nahr al-faṣāḥat. –4. Qatīl’s conversion and the linguistic idea of Iran. –Primary sources. –Secondary sources. Keywords Indo-Persian. Qatīl. Persian language. Lucknow. Shī‘a. Conversion. Nella storia del linguaggio i confini di spazio e di tempo, e altri, sono tutti pura fantasia (Bartoli 1910, p. -

Conversational Persian. INSTITUTION Peace Corps, Washington D

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 132 838 FL 008 233 AUTHOR Svare, Homa; :And Others TITLE Conversational Persian. INSTITUTION Peace Corps, Washington D. c. PUB DATE 66 NOTE 134p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$7.35 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Conversational Language Courses; indoEuropean Languages; *InstructionalHaterials; *Language Instruction; Language Programs; *Languagesfor Special Purposes; Language Usage;*Persian; *Second Language Learning; Textbooks;Vocabulary; Volunteers; Volunteer Training IDENTIFIERS Iran; *Peace corps ABSTRACT These language materials werefirst prepared at the State University of Utah inconnection with Peace Corps language programs in Persian. They arereproduced here with only slight modifications. This text is dividedinto seven main chapters: CO Persian Vocabulary and Expressionsfor History, Law and Government (this section contains dialoguessuch as the following: At the Doctor's Clinic, At the Bank, At theGrocery Store) ; (2)A Vocabulary of Useful Information (the PersianCalendar; Parts of the Body; Clothing and Personal Needs;Furniture and Household Needs; Profession and Trades; Sciences, Art andHumanities);(3) Persian Vocabulary and Expressions forBiology;(4) Persian Vocabulary and Expressions for Economics;(5) Technical Terminology;(6) Persian Vocabulary and Expressions forMathematics;(7) Persian Vocabulary and Expressions for Physicsand Chemistry; and (8) PersianVocabulary and Expressions for the Space Age.(CFM) Documents acquired by ERICinclude many informal unpublished effort * * materials not availablefrom other sources. ERIC makes every * to obtain the best copyavailable. Nevertheless, items ofmarginal * often encountered and this affectsthe quality * * reproducibility are * * of the microfiche andhardcopy: reproductions-ERIC makesavailable * via the ERIC DocumentReproduction Service (EDRS).EDRS is not * responsible for the qualityof the" original document.Reproductions * supplied by EDRS are the best that canbe made from the original. -

ZAS Papers in Linguistics

Zentrum für Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft, Sprachtypologie und Universalienforschung . ZAS Papers in Linguistics Volume 19 December 2000 Edited by EwaldLang Marzena Rochon Kerstin Schwabe I! Oliver Teuber ISSN 1435-9588 Investigations in Prosodie Phonology: The Role of the Foot and the Phonologieal Word Edited by T. A. Hall University of Leipzig Marzena Rochon Zentrum für Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft, Berlin ZAS Papers in Linguistics 19, 2000 Investigations in Prosodie Phonology: The Role of the Foot and the Phonologieal Word Edited by T. A. Hall & Marzena Roehon Contents 'j I Prefaee III Bozena Cetnarowska (University 0/ Silesia, Sosnowiec/Katowice, Poland) On the (non-) reeursivity of the prosodie word in Polish 1 Laum 1. Downing (ZAS Berlin) Satisfying minimality in Ndebele 23 T. A. Hall (University of Leipzig) The distribution of trimoraie syllables in German and English as evidenee for the phonologieal word 41 David J. Holsinger (ZAS Berlin) Weak position eonstraints: the role of prosodie templates in eontrast distribution 91 Arsalan Kahnemuyipour (University ofToronto) The word is a phrase, phonologieally: evidenee from Persian stress 119 Renate Raffelsiefen (Free University of Berlin) Prosodie form and identity effeets in German 137 Marzena RochOl1. (ZAS BerUn) Prosodie eonstituents in the representation of eonsonantal sequenees in Polish 177 Caroline R. Wiltshire (University of Florida, Gainesville) Crossing word boundaries: eonstraints for misaligned syllabifieation 207 ZAS Papers in Linguistics 19,2000 On the (non-)reeursivity ofthe prosodie word in Polish* Bozena Cetnarowska University of Silesia, Sosnowiec/Katowice, Poland 1 The problem The present paper investigates the relationship between the morphological word and the prosodie word in Polish sequences consisting of proclitics and lexical words. -

Introduction to the Iranian Languages Online Course

H-Mideast-Politics Introduction to the Iranian languages Online Course Discussion published by Khachik Gevorgyan on Wednesday, May 5, 2021 Armenian School of Languages and Cultures - ASPIRANTUM organizes an "Introduction to the Iranian languages" online course. The 2 weeks online school will start on June 21, 2021, and will last till July 2, 2021. This 2 weeks online school will be organized on working days each week (5 days each week, 10 days during two weeks) and will include 25 hours of intensive teaching (2.5 hours during each day). To apply and for more details please visit: https://aspirantum.com/courses/introduction-to-iranian-languages We are planning to start the online classes at 9 PM Yerevan time. This time is mainly comfortable for the students from European and American countries. Depending on applicants' geography, the time may be changed, and all applicants will be informed about the time changes before the course. The 2.5 hours class of each day will be divided into the following sections: First class - Homework, Lecture, Presentation, and Discussion Break Second class - Lecture, Presentation, and Discussion The course is offered by Prof. Vardan Voskanian (Yerevan State University), who, besides having thorough knowledge in the theory of the Iranian languages, hasmasterly knowledge of Kurdish, Talyshi, Pashto, Tati, Dari, Tajiki, and several other Old, Middle and New Iranian and Indian languages and dialects (beside Persian, in which he has a native-speaker fluency). Ruben Nikoghosyan will be the assistant professor of the course. Mr. Nikoghosyan has taught Middle Persian and Learn Persian through the Shahname online courses during 2020 and 2021 within ASPIRANTUM language school. -

The Boundaries of Afghans' Political Imagination

The Boundaries of Afghans’ Political Imagination The Boundaries of Afghans’ Political Imagination: The Normative-Axiological Aspects of Afghan Tradition By Jolanta Sierakowska-Dyndo The Boundaries of Afghans’ Political Imagination: The Normative-Axiological Aspects of Afghan Tradition, by Jolanta Sierakowska-Dyndo This book first published in Polish by the Warsaw University Press, 2007 00-497 Warszawa, ul. Nowy Świat 4, Poland e-mai:[email protected]; http://www.wuw.pl First published in English by Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK Translation into English by Teresa Opalińska British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2013 by Jolanta Sierakowska-Dyndo Cover image © Wiktor Dyndo All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-4229-X, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-4229-7 CONTENTS The Rules of Transcription........................................................................ vii Introduction ................................................................................................ ix Part I: Ethical Standards in the Afghan World Chapter One................................................................................................. 3 Pashtunwali: The Warrior Ethos -

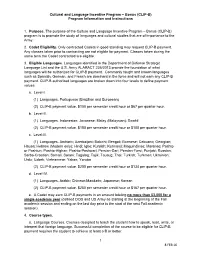

Cultural and Language Incentive Program – Bonus (CLIP-B) Program Information and Instructions

Cultural and Language Incentive Program – Bonus (CLIP-B) Program Information and Instructions 1. Purpose. The purpose of the Culture and Language Incentive Program – Bonus (CLIP-B) program is to promote the study of languages and cultural studies that are of importance to the Army. 2. Cadet Eligibility. Only contracted Cadets in good standing may request CLIP-B payment. Any classes taken prior to contracting are not eligible for payment. Classes taken during the same term the Cadet contracted are eligible. 3. Eligible Languages. Languages identified in the Department of Defense Strategic Language List and the U.S. Army ALARACT 236/2013 provide the foundation of what languages will be authorized for CLIP-B payment. Commonly taught and known languages such as Spanish, German, and French are dominant in the force and will not earn any CLIP-B payment. CLIP-B authorized languages are broken down into four levels to define payment values. a. Level-I. (1) Languages. Portuguese (Brazilian and European) (2) CLIP-B payment value. $100 per semester credit hour or $67 per quarter hour. b. Level-II. (1) Languages. Indonesian; Javanese; Malay (Malaysian); Swahil (2) CLIP-B payment value. $150 per semester credit hour or $100 per quarter hour. c. Level-III. (1) Languages. Amharic; Azerbaijani; Baluchi; Bengali; Burmese; Cebuano; Georgian; Hausa; Hebrew (Modern only); Hindi; Igbo; Kurdish; Kurmanji; Maguindinao; Maranao; Pashto or Pashtun; Pashto-Afghan; Pashto-Peshwari; Persian-Dari; Persian-Farsi; Punjabi; Russian; Serbo-Croatian; Somali; Sorani; Tagalog; Tajik; Tausug; Thai; Turkish; Turkmen; Ukrainian; Urdu; Uzbek; Vietnamese; Yakan; Yoruba (2) CLIP-B payment value. $200 per semester credit hour or $134 per quarter hour.