Urban Renewal in the Colonial Capital: Contextualizing the Williamsburg Redevelopment & Housing Authority

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tuesday, April 25, 2017 10 A.M. to 5 P.M

224 Tuesday, April 25, 2017 Williamsburg10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Photo courtesy of Nina Mustard Homes on this nine-property tour span in age from the beginning of the 18th century to a 21st century Colonial Revival. All are conveniently concentrated in two neighborhoods located near each other. Visitors will appreciate interiors that sparkle with floral designs by the Williamsburg Garden Club complementing spectacular antiques and artwork. Not to be outdone, the gardens of featured properties are prime examples of 18th century to current landscaping styles and include a city farm garden, shade gardens, a school garden, as well as formal and cottage gardens that represent the Williamsburg style. This year’s tour features five private properties in the College Terrace neighborhood that are opened for the first time for Historic Garden Week in addition to Historic Area properties and gardens - a full day of touring with 11 sites total. Start at the William and Mary Alumni house, which serves as tour headquarters, and walk or use the tour shuttle, included in the ticket. Enjoy lunch at the many establishments in Merchant’s Square and Colonial Williamsburg. Hosted by The Williamsburg Garden Club Chairmen Tickets: $50 pp. Cash/Check/Credit Card Dollie Marshall and Linda Wenger accepted at the following locations. Tick- [email protected] ets available at the Colonial Williamsburg Visitors Center on Monday, April 24, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., and on Tuesday, April 25, 9 Advance and Tour Bus Ticket Sales Chairman a.m. until noon. Tickets are also available on tour day beginning at 9:30 a.m. -

Bulletin of the College of William and Mary in Virginia

c ii.A^ .-\^ -¥- Vol. 34, No. 3 BULLETIN March, 1940 of The College of William and Mary IN Virginia CATALOGUE of W^t College of l^illiam anb iMarp in Virginia Two Hundred and Forty-Seventh Yeah 1959-mo Announcements , Session 1940-1941 WILLIAMSBURG, VIRGINIA 1940 Entered at the post office at Williamsburg, Virginia, July 3, 1926, under act of August 24, 1912, as second-class matter Issued January, February, March, April, June, August, November Entered at the post office at Williamsburg, Virginia, July 3, 1926, under act of August 24, 1912, as second-class matter Issued January, February, March, April, June, August, November Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from LYRASIS IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/bulletinofcolleg343coll Wren Building—East Front Showing Lord Botetourt's Statue Vol. 34, No. 3 BULLETIN March, 1940 of The College of William and Mary IN Virginia CATALOGUE W^t College of William anb iHarp in Two Hundred and Forty-Seventh Year 1939-1940 Announcements i Session 1940-1941 WILLIAMSBURG, VIRGINIA 1940 Entered at the post office at Williamsburg, Virginia, July 3, 1926, under act of August 24, 1912, as second-class matter Issued January, February, March, April, June, August, November CONTENTS Page Calendar 4 College Calendar 5 Board of Visitors 6 Standing Committees of the Board of Visitors 7 OflScers of Administration 8 Officers of Instruction 9 Standing Committees of the Faculty 18 Special Lecturers 21 Alumni Association 22 Societies and Publications 24 Athletics for Men 26 -

Colonial Williamsburg to Resume Limited Onsite Programming June 14

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation P.O. Box 1776 Williamsburg, Va. 23187-1776 colonialwilliamsburg.org Colonial Williamsburg to Resume Limited Onsite Programming June 14 Select sites to reopen at reduced capacity, changes to guest experience; face coverings and social distancing required for staff and guests inside foundation-owned buildings Colonial Williamsburg will resume limited public programming at select sites on June 14. This first wave of openings is based on Virginia’s move into Phase 2 of the state’s Forward Virginia initiative. The foundation will open additional sites and expand programming in coming weeks and months pending government and public health guidance to further limit health risks associated with COVID-19. “We are eager to welcome employees and guests back to Colonial Williamsburg, but re- opening our public sites requires that we work together so that we all remain safe,” said President and CEO Cliff Fleet. “Our phased re-opening plan is based on state guidelines and is fully supported by our regional partners. With this plan in place, we can move at a measured pace toward our shared goal of a return to normal operations.” The following Colonial Williamsburg indoor and open-air sites will operate at reduced capacity and follow site-specific safety guidelines developed as part of the foundation’s COVID-19 business resumption plan, which is consistent with the state’s Phase 2 requirements: • The Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg • Governor’s Palace • Capitol • Courthouse • Weaver trade shop • Carpenter’s Yard • Peyton Randolph Yard • Colonial Garden • Magazine Yard • Armoury Yard • Brickyard • George Wythe Yard • Custis Square, including tours The Williamsburg Lodge is currently open with additional hospitality operations expanding based on sustainable business demand. -

NATIONAL REGISTER of HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM Williamsburg Historic District

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK 3-2a Development of the English Colonies, 1700-1775; Intracolonial matters Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Virginia COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Williamsburg (ind. city) INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NFS USE ONLY ENTRY DATE (Type all entries complete applicable sections) '^'. ( : •'•.:;:^ • ' ' . ': : :; t :.^ ..,-•'. .... : ... ' -.. ""•:.- T " •••.:.•,; • " - : " . ; - ' : '-: . -^ COMMON: Williamsburg Historic District AND/OR HISTORI C: Williamsburg Historic District teJ0gAT*ON STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: CON GRESSIONAL DISTRICT: Williamsburg First flstl STATE CODE COU NTY: CODE Virginia 25185 51 [Vil liamsburg (ind. citv) S3fi K^Q^^^^fOiN. •• • ••' • ••'•'• STATUS ACCESSIBLE CATEGORY OWNERSHIP (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC DCX District G Building 1 1 Public Public Acquisit on: ^^ Occupied Yes: G Site G Structure KX Private Q In Process Q Unoccupied D Restricted G Object G Both Q Being Considered Q Preservation work ^ Unrestricted in progress ' — ' PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) 1 1 Agricultural [ | Government [ | Park 1 1 Transportation 1 1 Comments X3 Commercial 1 1 Industrial | | Private Residence G Other (Specify) )Q§ Entertainment 1X1 Museum | | Scientific f:i : :-:: Y^ttf JSj'F^'t? '"fil*1 ' P'fi?"rt'P 5* C?TY - -. " • " • ''..•:'.':'-.: .-.,:'':-'•.>-:'•'!' -':: :'."•:•'!-:' '•":'• .•','.•":.' : ' "'''-.': •*.'.' -. .-: -->•'•"': ••''-.'•' .'•'••'. V: x: ".•.•'•:;£ !'.;£ OWNER'S NAME: STATE- Colonial Williamsburg, Inc. STREET AND NUMBER: Godwin Building, Box C CITY OR TOWN: STATE: CODF Williamsburg Virginia 25185 51 |Sij|$CAli$N $F; iyt&fci; 0e $£ R 1 P T i ON ' • " '• • , •'''•-."" "•• .' '; • :•:': "•= . •: : • •• - COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: COUNTY: City Hall STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: STATE CODE Williamsburg Virginia 25185 51 pgJiIPsMliNif i«kifilN IN :-i:x i:iTiNi'' su R v e V ^ • ' " "'".."•'. -

The First Labor History of the College of William and Mary

1 Integration at Work: The First Labor History of The College of William and Mary Williamsburg has always been a quietly conservative town. Throughout the first half of the twentieth century to the time of the Civil Rights Act, change happened slowly. Opportunities for African American residents had changed little after the Civil War. The black community was largely regulated to separate schools, segregated residential districts, and menial labor and unskilled jobs in town. Even as the town experienced economic success following the restoration of Colonial Williamsburg in the early 1930s, African Americans did not receive a proportional share of that prosperity. As the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation bought up land in the center of town, the displaced community dispersed to racially segregated neighborhoods. Black residents were relegated to the physical and figurative margins of the town. More than ever, there was a social disconnect between the city, the African American community, and Williamsburg institutions including Colonial Williamsburg and the College of William and Mary. As one of the town’s largest employers, the College of William and Mary served both to create and reinforce this divide. While many African Americans found employment at the College, supervisory roles were without exception held by white workers, a trend that continued into the 1970s. While reinforcing notions of servility in its hiring practices, the College generally embodied traditional southern racial boundaries in its admissions policy as well. As in Williamsburg, change at the College was a gradual and halting process. This resistance to change was characteristic of southern ideology of the time, but the gentle paternalism of Virginians in particular shaped the College’s actions. -

Chapter 9 - Institutions

Chapter 9 - Institutions INSTITUTIONS Since its establishment in 1699, Williamsburg has been defined by its major public institutions. William & Mary and Bruton Parish Church preceded the city and were its first institutional partners. Virginia’s colonial government was based here from Williamsburg’s founding in 1699 until the capital was moved to Richmond in 1780. The Publick Hospital, which became Eastern State Hospital, was a significant presence in the city from 1773 until completing its move to James City County in 1970. Finally, the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation traces its origin to 1926, when John D. Rockefeller, Jr. began the Colonial Capital restoration. William & Mary and Colonial Williamsburg comprise 43% of the city’s total land area. This chapter will discuss the impact of these two institutions on the city. 2021 Comprehensive Plan Chapter 9 - Institutions Page 9-1 Chapter 9 - Institutions WILLIAM & MARY William & Mary, one of the nation’s premier state-assisted liberal arts universities, has played an integral role in the city from the start. The university was chartered in 1693 by King William III and Queen Mary II and is the second oldest higher educational institution in the country. William & Mary’s total enrollment in the fall of 2018 was 8,817 students, 6,377 undergraduate, 1,830 undergraduate, and 610 first-professional students. The university provides high-quality undergraduate, graduate, and professional education comprised of the Schools of Arts and Sciences, Business Administration, Education, Law, and Marine Science. The university had 713 full-time faculty members and 182 part-time faculty members in 2018/19. The university’s centerpiece is the Wren Building, attributed apocryphally to the English architect Sir Christopher Wren. -

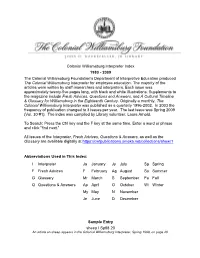

Colonial Williamsburg Interpreter Index 1980

Colonial Williamsburg Interpreter Index 1980 - 2009 The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's Department of Interpretive Education produced The Colonial Williamsburg Interpreter for employee education. The majority of the articles were written by staff researchers and interpreters. Each issue was approximately twenty-five pages long, with black and white illustrations. Supplements to the magazine include Fresh Advices, Questions and Answers, and A Cultural Timeline & Glossary for Williamsburg in the Eighteenth Century. Originally a monthly, The Colonial Williamsburg Interpreter was published as a quarterly 1996-2002. In 2003 the frequency of publication changed to 3 issues per year. The last issue was Spring 2009 (Vol. 30 #1). The index was compiled by Library volunteer, Laura Arnold. To Search: Press the Ctrl key and the F key at the same time. Enter a word or phrase and click "find next.” All issues of the Interpreter, Fresh Advices, Questions & Answers, as well as the Glossary are available digitally at https://cwfpublications.omeka.net/collections/show/1 Abbreviations Used in This Index: I Interpreter Ja January Jy July Sp Spring F Fresh Advices F February Ag August Su Summer G Glossary Mr March S September Fa Fall Q Questions & Answers Ap April O October Wi Winter My May N November Je June D December Sample Entry sheep I Sp98 20 An article on sheep appears in the Colonial Williamsburg Interpreter, Spring 1998, on page 20. A abolition of slavery I Sp99 20-22, I Wi99/00 19-25, “Abuse of History: Selections from Dave Barry Slept Here, -

Tuesday, April 24, 2018 10 A.M. to 5 P.M. 228

228 Williamsburg 229 $17 per box lunch (gluten free and Ticket includes Escorted Walking Tour vegetarian options available) served at the private Two Rivers Country Club of Colonial Williamsburg Gardens, 11:30 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. Cash bar avail- Colonial Williamsburg bus transportation, able. Contact Cathy Adams, cbtbka@cox. shuttle bus service in Governor’s Land, net or (757) 220-2486 by April 15 to and admission to the following properties: reserve and prepay. Facilities: Colonial Williamsburg Region- al Visitors Center, Colonial Williamsburg Colonial Williamsburg Tour Merchants Square Ticket Office and the Two Rivers Country Club. The Lightfoot House Williamsburg 120 East Francis Street The James River Historic Plantations Tour is a separate tour. Advance tickets This imposing Georgian mansion was are available at www.vagardenweek.org or likely a two-and-a-half story, double tene- at the plantations on the day of their tour. ment when originally built c. 1730. It was converted to its present form to serve as Complimentary and available at a townhouse for the prominent Lightfoot Colonial Williamsburg Regional Visi- family. Col. Philip Lightfoot III, a wealthy Tuesday, April 24, 2018 tor Center. In Governor’s Land, parking is Yorktown merchant and planter, resid- available at Park East Community Build- ed here when his position as Councilor 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Photo courtesy of Sigmon Taylor ing on Two Rivers Rd. brought him to Williamsburg. The Light- foot House is distinguished architectural- HGW ticket holders board Colonial ly by the belt course of molded brick that Williamsburg buses for transportation complements the Flemish bond pattern of to and from the Visitors Center and around the outside walls. -

Minutes of the Business Meeting 16 Oct 2014

150th Anniversary of the American Civil War 609-463-9277 or 741-5438 [email protected] Secretary: Pat Munson-Siter 42 Franklin Ave., Villas, NJ 08251-2407 609-287-5097 [email protected] Treasurer: Jim Marshall 202 Bartram Ln., Ocean City, NJ 08226 609-602-3243 [email protected] Minutes of the Business Meeting 16 Oct 2014 President Runner called the meeting to order. We saluted the flag and held a moment of silence for those who stand in harm’s way to protect us. He also called for prayers for those of our members and their families who are facing major health issues. Dues next year – Rising costs for materials (newsletters, postage, etc) as well as higher speaker’s fees (including lodging for some speakers) is eating into our operating budget. It has been more than 10 years since our last dues increase. Treasurer reports that he ran the numbers, and increasing the dues to $30 would allow us to take in about what we are spending. It was also decided to end the extra $5 for ‘family membership.’ Suggestion was made to up dues to $35 for those members who want us to mail them a hardcopy of the newsletter to cover copy and postage costs. After much debate, the motion to increase Cape May County Civil War Round Table Newsletter the dues to $30, $35 for membership with mailed November 2014 newsletter, was seconded and approved. Further, it was decided that as of 1 January 2015, Meeting Schedule the only members receiving hard copies of the newsletter Meetings are at the Jury Room in the Court House in Cape May Court House, and start at 6:30pm will be those who have specifically requested them. -

Final Summary Report April 2, 2014

Final Summary Report April 2, 2014 Prepared by the Planning Staffs of James City County City of Williamsburg York County INTRODUCTION In 2006, at the recommendation of the Regional Issues Committee and the three Planning Commissions, the governing bodies of James City County, the City of Williamsburg, and York County agreed to coordi‐ nate the timing of their next comprehensive plan reviews. Each of the three localities has an adopted comprehensive plan – a long‐range plan for the physical development of the area within its jurisdiction – and by state law these plans must be reviewed at least once every five years. While Williamsburg and York County conducted extensive reviews of their respective comprehensive plans, which were last up‐ dated in 2006 and 2005 respectively, James City County undertook a more targeted review of its plan since it was adopted fairly recently (2009). The purpose of the coordinated timing was to promote closer collaboration and communication concerning land use, transportation, and other comprehensive plan issues that cross jurisdictional boundaries. It was agreed from the outset that each locality would be conducting its own independent comprehensive plan review and developing its own plan, the coordi‐ nated timing of these reviews was intended to provide an opportunity for citizens of all three localities to talk about issues of mutual interest. This is just one of many examples of inter‐jurisdictional coopera‐ tion among the three localities. Others include the Williamsburg Area Transport system, the Williams‐ burg Regional Library system, the Regional Bikeway Plan, the Historic Triangle Bicycle Advisory Commit‐ tee, and the Regional Issues Committee. -

The Magazine

The Magazine Williamsburg Chapter Virginia Society Sons of the American Revolution By signing the Declaration of Independence, the fifty-six Americans pledged their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor. Nine died of wounds during the Revolutionary War, Five were captured or imprisoned. Wives and children were jailed, mistreated, or left penniless. Twelve signers’ houses were burned to the ground. No signer defected. Their honor, like their nation remained intact. Vol. XX President’s Message I never tire of reading the story about the If we can apply these lessons in our own times, no signers of the Declaration of Independence matter the difficulties, we, of the SAR, will have printed under the masthead of our newsletter, helped keep intact this unique and blessed nation and I never tire of reading some of the closing that our patriot ancestors sacrificed so much to paragraphs in David McCullough’s famous create. book “1776.” In it he writes, “the year 1776, In order to recognize SAR member veterans, our celebrated as the birth year of the nation and National Society has established five Veterans for the signing of the Declaration of Corps: WWII, Korea, Vietnam, S.W. Asia, and Independence, was for those who carried the Military Service. At our most recent meeting fight for independence forward a year of all- Bob Davis, our Veterans Affairs Chair, awarded too-few victories, of defeat and seven Certificates and Medals of Patriotism. discouragement.” But “Washington never gave More are being processed and Bob invites our up. Again and again, in letters to Congress and veteran members to contact him about making an to his officers, and in his general orders, he application. -

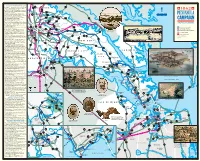

Pen. Map Side

) R ★ MARCH UP THE PENINSULA★ R c a 360 ★ 95 te R Fort Monroe – Largest moat encircled masonry fortifi- m titu 1 Ins o ry A cation in America and an important Union base for t HANOVER o st Hi campaigns throughout the Civil War. o ry P ita P 301 il M P ★ y Fort Wool–Thecompanionfortification to Fort Monroe. m & r A A 2 . The fort was used in operations against Confederate- Enon Church .S g U H f r o held Norfolk in 1861-1862. 606 k y A u s e e t b Yellow Tavern e r ★ r u N Hampton – Confederates burned this port town o s C (J.E.B. Stuart y C to block its use by the Federals on August 7, 1861. k Tot opotomo N c 295 Monument) 643 P i O r • St. John’s Church – This church is the only surviving A C e Old Church K building from the 1861 burning of Hampton. M d Polegreen Church 627 e 606 R • Big Bethel – This June 10, 1861, engagement was r 627 U I F 606 V the first land battle of the Civil War. 628 N 30 E , K R ★ d Bethesda E Monitor-Merrimack Overlook – Scene of the n Y March 9, 1862, Battle of the Ironclads. o Church R I m 615 632 V E ★ Congress and Cumberland Overlook – Scene of the h R c March8,1862, sinking of the USS Cumberland and USS i Cold Harbor R 156 Congress by the ironclad CSS Virginia (Merrimack).