Sloanselect Leadership Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lou Donaldson the Natural Soul Mp3, Flac, Wma

Lou Donaldson The Natural Soul mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: The Natural Soul Country: US Released: 1986 Style: Soul-Jazz, Hard Bop MP3 version RAR size: 1767 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1621 mb WMA version RAR size: 1543 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 259 Other Formats: MP3 VOC WMA MP4 DTS DXD AA Tracklist Hide Credits Funky Mama A1 9:05 Written-By – John Patton Love Walked In A2 5:10 Written-By – George & Ira Gershwin Spaceman Twist A3 5:35 Written-By – Lou Donaldson Sow Belly Blues B1 10:11 Written-By – Lou Donaldson That's All B2 5:33 Written-By – Alan Brandt, Bob Haymes Nice 'N Greasy B3 5:24 Written-By – Johnny Acea Companies, etc. Copyright (c) – Manhattan Records Phonographic Copyright (p) – Manhattan Records Recorded At – Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey Credits Alto Saxophone – Lou Donaldson Design [Cover] – Reid Miles Drums – Ben Dixon Guitar – Grant Green Liner Notes – Del Shields Organ – John Patton Photography By [Cover Photo] – Ronnie Brathwaite Producer – Alfred Lion Recorded By [Recording By] – Rudy Van Gelder Trumpet – Tommy Turrentine Notes Recorded on May 9, 1962. 1986 Manhattan Records, a division of Capitol Records, Inc. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year The Natural Soul (LP, BLP 4108 Lou Donaldson Blue Note BLP 4108 US 1963 Album, Mono) The Natural Soul (CD, CDP 7 84108 2 Lou Donaldson Blue Note CDP 7 84108 2 US 1989 Album, RE) TOCJ-7176, The Natural Soul (CD, Blue Note, TOCJ-7176, Lou Donaldson Japan 2008 BST-84108 Album, RE) Blue Note BST-84108 The Natural Soul 4BN 84108 Lou Donaldson Blue Note 4BN 84108 US 1986 (Cass, Album, RM) The Natural Soul (LP, BST-84108 Lou Donaldson Blue Note BST-84108 US 1973 Album, RE) Related Music albums to The Natural Soul by Lou Donaldson Lou Donaldson - Mr. -

Bob Dylan – the Original Mono Recordings

Bob Dylan – The Original Mono Recordings by Roger Ford The eight albums in this box are of course the foundation of a sound that was still integrated but with added presence Bob Dylan’s career and legend, the records that made him and depth. famous. But more specifically, these are the records that made him famous – not the albums as they sound on the But technology marched on, and the mono versions of standard CDs today, not the earlier generation of CDs from Dylan’s LPs were discontinued in 1968 in the US, a year later the late ’80s, not even the stereo LPs that came out as each in the UK, and as far as I know had disappeared from all other record was made. It was the mono LPs (and the singles taken parts of the world by the mid -’70s. For the last quarter of the from them) that people heard on the radio, round at friends’ 20 th century they were completely unavailable, and once houses, in record shops. These were the sounds that were people realised what had been lost, good condition original engraved into the memory of anyone who listened to Dylan copies became increasingly sought after. in the sixties. The mono albums were eventually reissued by the US specialist reissue label Sundazed between 2001 and 2004, though only in vinyl format. They were remastered by Sundazed owner Bob Irwin, a well-respected audio engineer in his own right. Irwin put a lot of work into finding the right master tapes as well as into the remastering process itself, but nonetheless these editions evoked a somewhat mixed response, with some albums better received than others. -

BENNY GOLSON NEA Jazz Master (1996)

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. BENNY GOLSON NEA Jazz Master (1996) Interviewee: Benny Golson (January 25, 1929 - ) Interviewer: Anthony Brown with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: January 8-9, 2009 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 119 pp. Brown: Today is January 8th, 2009. My name is Anthony Brown, and with Ken Kimery we are conducting the Smithsonian National Endowment for the Arts Oral History Program interview with Mr. Benny Golson, arranger, composer, elder statesman, tenor saxophonist. I should say probably the sterling example of integrity. How else can I preface my remarks about one of my heroes in this music, Benny Golson, in his house in Los Angeles? Good afternoon, Mr. Benny Golson. How are you today? Golson: Good afternoon. Brown: We’d like to start – this is the oral history interview that we will attempt to capture your life and music. As an oral history, we’re going to begin from the very beginning. So if you could start by telling us your first – your full name (given at birth), your birthplace, and birthdate. Golson: My full name is Benny Golson, Jr. Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The year is 1929. Brown: Did you want to give the exact date? Golson: January 25th. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 2 Brown: That date has been – I’ve seen several different references. Even the Grove Dictionary of Jazz had a disclaimer saying, we originally published it as January 26th. -

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL Recordings of the Year 2017

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL Recordings Of The Year 2017 This is the fourteenth year that Musicweb International has asked its reviewing team to nominate their recordings of the year. Reviewers are not restricted to discs they had reviewed, but the choices must have been reviewed on MWI in the last 12 months (December 2016-November 2017). The 136 selections have come from 27 members of the team and 68 different labels, the choices reflecting as usual, the great diversity of music and sources. Of the selections, seven have received two nominations: Iván Fischer’s Mahler 3 on Channel Classics Late works by Elliott Carter on Ondine Tommie Haglund’s Cello concerto on BIS Beatrice Rana’s Goldberg Variations on Warner Unreleased recordings by Wanda Luzzato on Rhine Classics Krystian Zimerman’s late Schubert sonatas on Deutsche Grammophon Vaughan Williams London Symphony on Hyperion Two labels – Deutsche Grammophon and Hyperion – gained the most nominations, nine apiece, considerably more than any other label. MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL RECORDING OF THE YEAR In this twelve month period, we published more than 2700 reviews. There is no easy or entirely satisfactory way of choosing one above all others as our Recording of the Year. In some years, there have been significant anniversaries of composers or performers to help guide the selection, but not so in 2017. Johann Sebastian BACH Goldberg Variations - Beatrice Rana (piano) rec. 2016 WARNER CLASSICS 9029588018 In the end, it was the unanimity of the two reviewers who nominated Beatrice Rana’s Goldberg Variations – “easily my individual Record of the Year” and “how is it possible that she can be only 23” – that won the day. -

Career Advancement for Construction Executives

CCAARREEEERR AADDVVAANNCCEEMMEENNTT FFOORR CCOONNSSTTRRUUCCTTIIOONN EEXXEECCUUTTIIVVEESS PPART II —— FFOR THE EEXECUTIVE CCANDIDATE Frederick C. Hornberger, Jr. http://www.hmc.com http://www.constructionexecutive.com Copyright 2010 Hornberger Management Company – Construction Recruiter. All Rights Reserved. CAREER ADVANCEMENT FOR CONSTRUCTION EXECUTIVES Table of Contents Career Advancement for Construction Executives — Part I — For the Executive Candidate.......1 About Frederick C. Hornberger, Jr. .............................................................................................3 Creating Resumes That Sell ........................................................................................................5 You’ve Got To Dream It Before You Can Do It ........................................................................13 Talk To Those Who Are There; Draw A Map To Get There......................................................18 Zeroing In On Your Target........................................................................................................25 Personal Integrity — The Key Ingredient in Any Career ...........................................................30 If You’re Willing to Work, Be Willing to Learn How ...............................................................38 Building a Dependable Network of Relationships......................................................................53 Timely Career Moves................................................................................................................61 -

Instead Draws Upon a Much More Generic Sort of Free-Jazz Tenor Saxophone Musical Vocabulary

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. SLIDE HAMPTON NEA Jazz Master (2005) Interviewee: Slide Hampton (April 21, 1932 - ) Interviewer: William A. Brower with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: April 20-21, 2006 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 117 pp. Brower: My name is William A. Brower. It is Thursday, April 20, 2006. I’m in Carmichael Auditorium, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History, conducting an interview with Slide Hampton. Recording the interview is Ken Kimery. Would you start off, Mr. Hampton, by giving us your full name and date of birth? Hampton: My name is Locksley Wellington “Slide” Hampton. I was born in Jeannette, Pennsylvania, April 21, 1932. Brower: That means tomorrow you are seventy- Hampton: -four. Brower: Let’s start in Jeannette, Pennsylvania. Can you give us a little information about the town and what you recollect of being born there, and your early years? Hampton: I didn’t live there very long, but I do remember very strongly that in Jeannette, for some reason I got the impression that all of America was integrated, because we lived in a family – we shared a house with a white family and our family. I thought that it was that way everywhere until we left Jeannette. Then immediately it changed. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 2 Brower: So you were living in a duplex, two-family home? Hampton: Yes, two-family home. -

COLLECTED 2019 1 Writer Name

COLLECTED 2019 1 Writer Name Writer SAIC MFA IN WRITING COLLECTED ‘19 COLLECTED 2019 SAIC MFA IN WRITING 4 5 EDITORIAL LETTER This year’s Collected is an eclectic fusion of text and image centered around the concept of Disassemble: a breaking down, chiseling, smoothening out, and then creating new frameworks to retell, revise or reimagine existing narratives, - aiming to reveal how the self can be invented in this process. We began this journey almost two years ago. The Fall of 2017 ushered in a group of people who were a stone’s throw away, a day’s worth of horseback riding and a sailor’s round trip. Rattling different weights & colours of pebbles won’t meld them together – instead, it recreates a distinguishable orientation, tethers others closely, isolates temporarily and reunites into a welcome newness. And so it was with the MFAW class of 2019. Though we were separate in our identities, our modes of expression, and our experiences, we came together much like a mosaic -- a kaleidoscope of jeweled colors - when fit together create a mural, a multi-layered story of who we hope to be. The premise of our time here as writers-in-training was and has always been about collaboration: with versions of the self, with each other, with the institution. As writers and makers, we bent genre, explored form, found faith again and again on the page and beyond. We invited our histories to fill in the silences we wrestled with. We deepened our understanding of emotion through color and sound. We dismantled our fears through painting, reconstructed our strength in the face of historical, generational, and personal trauma with poetry. -

The Frats Are at It Again SMC Activities for Next Week

Homecoming 71 It’s all over.. by Larry Marion “ Coming up,” theme for Dre xel’s 1971 Homecoming, was car icatured by a huge tuition .bill reflecting the constant tuition increases, and a disappointing turnout at the Sugarloaf concert. Over 400 tickets were sold to THISTLETHWAITE the two shows and champagne party bash held last Friday night Drexel’s homecoming queen is safely delivered by helicopter. in the Main Auditorium and the DAC, the 7:30 p.m. show was the most popular, drawing over 300 people, the rest showed up for Verne Cozzolino the 9:30 show. “Wax,” the bright football game. (See sports The frats are at it again back-up group for the two shows pages). The Queen and her court were delivered to the field by Don Hendler shorted out all their electronic Last week Drexel’s fraternities erupted once equipment, and consequently did by the ARCO helicopter, pro Last Friday, representatives of the twelve fra vided free by those friendly pol again. This time their activities Involved paint not perform the second show. ternities met to determine a procedure for handling luters. throwing and fistfighting by brothers of three of “ 1200 roast beef sandwiches, incidents of this type. In order to become an of Many students felt that the the University’s twelve frats. The participants 480 bottles of Cold Duck cham ficial part of the I-F bylaws; however, such a pro Sugarloaf concert was more in this particular melee were brothers from pagne, and 1000 champagne cedure must be ratified by members of the I.E. -

Here Are Many Things That I Look Forward To, but the Focus for Me Is My Instrument Lessons

CONTENTS Introduction 6 Study With Us 13 Performance 20 Celebrating Success 28 Support and Welfare 37 Join Us 42 ‘Attending Junior RNCM has been a wonderful opportunity for my daughter to share her passion and aspirations with other talented and like-minded people. She has been inspired by new approaches to composition, and through Academic Studies has developed a huge desire to understand how and why music works in the way that it does.’ Jayne, Junior RNCM parent 4 5 Introduction Introduction INTRODUCTION Junior RNCM is a vibrant community of gifted young musicians aged 8 to 18 who come together to develop their talent within Manchester’s inspirational Royal Northern College of Music. Every Saturday during term time the RNCM is their home; a place to study with exceptional tutors, perform with like- minded people and make long-lasting friendships. It’s also a place that looks to the future, teaching transferable skills for life and creating a solid platform for further study at a conservatoire or university. Being part of Junior RNCM is special. Students often say it’s their favourite part of the week and many tutors are proud to be alumni of the school. The varied curriculum ensures that everyone who trains with us receives an outstanding music education within an environment full of opportunity. ‘I particularly enjoy creating a range of opportunities, enabling each student to flourish in their music making. Everyone at Junior RNCM is treated as an individual and encouraged to follow their own bespoke path.’ Karen Humphreys MBE, Head of Junior RNCM 6 7 Introduction Introduction ‘Junior RNCM provides first rate instrumental and musical training to talented and gifted youngsters. -

Title Format Released (Jerry Bergonzi/Bobby Watson/Victor Lewis) Together Again for the First Time CD 1997 ???? ????? CD 1990 4

Title Format Released (Jerry Bergonzi/Bobby Watson/Victor Lewis) Together Again For The First Time CD 1997 ???? ????? CD 1990 4 Giants Of Swing 4 Giants Of Swing CD 1977 Abate, Greg It'S Christmastime CD 1995 Monsters In The Night CD 2005 Evolution CD 2002 Straight Ahead CD 2006 Bop City: Live At Birdland CD 2006 Abate, Greg Quintet Horace Is Here CD 2004 Bop Lives CD 1996 Adams, George & Don Pullen Don't Lose Control CD 1979 Adams, Greg Midnight Morning CD 2002 Adams, Pepper 10 to 4 at the 5-Spot CD 1958 Adderley, Cannonball The Poll Winners: Volume 4 CD 1960 The Cannonball Adderley Quintet In San Francisco [Live] [Bonus Track] CD 1959 Adderley, Cannonball With Bill Evans Know What I Mean? CD 1961 Adderley, Nat Work Song CD 1990 Ade & His African Beats, King Sunny Juju Music CD 1982 Aggregation, The Groove’s Mood CD 2008 Akiyoshi, Toshiko Desert Lady/Fantasy CD 1993 Live at Maybeck Recital Hall: Volume 36 CD 1994 Finesse CD 1978 Alaadeen and the deans of swing Aladeen And The Deans Of Swing Plays Blues For RC And Josephine, Too CD 1995 Alaadeen, Ahmad New Africa Suite CD 2005 Time Through The Ages CD 1987 Page 1 of 79 Title Format Released Albany, Joe The Right Combination CD 1957 Alden, Howard & Jack Lesberg No Amps Allowed CD 1988 Alexander, Eric Solid CD 1998 Alexander, Monty Goin' Yard CD 2001 Jamboree CD 1998 Ray Brown Trio - Ray Brown Monty Alexander Russell Malone (Disc 2-2) CD 2002 Reunion in Europe CD 1984 Ray Brown Monty Alexander Russell Malone (Disc 1) CD 2002 My America CD 2002 Monty Meets Sly And Robbie CD 2000 Stir It -

Drops That Open Worlds. Image of Water in the Poetry of Euphrase

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto Drops That Open Worlds Image of Water in the Poetry of Euphrase Kezilahabi Katriina Ranne Master’s Thesis University of Helsinki Faculty of Arts Institute for Asian and African Studies African Studies May 2006 Tiedekunta/Osasto ҟ Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Laitos ҟ Institution – Department Humanistinen tiedekunta Aasian ja Afrikan kielten ja kulttuurien laitos TekijäҏҟҏFörfattare – Author Ranne, Katriina Työn nimiҏҟ Arbetets titel – Title Drops That Open Worlds –The Image of Water in the Poetry of Euphrase Kezilahabi Oppiaine ҟ Läroämne – Subject Afrikan-tutkimus Työn lajiҏҟ Arbetets art – Level Aikaҏҟ Datum – Month and year Sivumääräҏҟ Sidoantal – Number of pages Pro gradu Toukokuu 2006 99 s. + runoliite 34 s. Tiivistelmäҏҟ Referat – Abstract Euphrase Kezilahabi on tansanialainen kirjailija, joka ensimmäisenä julkaisi swahilinkielisen vapaalla mitalla kirjoitetun runokokoelman. Perinteisessä swahilirunoudessa tiukat muotosäännöt ovat tärkeitä, ja teos synnytti kiivasta keskustelua. Runoteokset Kichomi (‘Viilto’, ‘Kipu’, 1974) ja Karibu Ndani (‘Tervetuloa sisään’, 1988) sekä Kezilahabin muu tuotanto voidaan nähdä uuden sukupolven taiteena. Kezilahabi on arvostettu runoilija, mutta hänen runojaan ei aiemmin ole käännetty englanniksi (yksittäisiä säkeitä lukuunottamatta), eikä juurikaan tutkittu yksityiskohtaisesti. Yleiskuvaan pyrkivissä lausunnoissa Kezilahabin runouden on hyvin usein määritelty olevan poliittista. Monet Kezilahabin runoista ottavatkin kantaa yhteiskunnallisiin kysymyksiin, mutta niiden pohdinta on kuitenkin runoissa vain yksi taso. Sen lisäksi Kezilahabin lyriikassa on paljon muuta ennen kartoittamatonta –tämä tutkimus keskittyy veden kuvaan (the image of water). Kezilahabi vietti lapsuutensa saarella Victoria-järven keskellä, ja hänen vesikuvastonsa on rikasta. Tutkimuskysymyksenä on, mitä veden kuva runoteoksissa Kichomi ja Karibu Ndani esittää. -

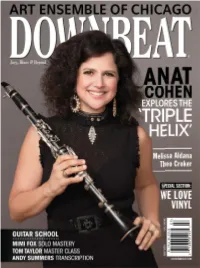

DB1907 Test.Pdf

JuLY 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 7 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; Denmark: Jan Persson; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert.