412 and Beneficial to Further Studies. in Contrast to This Precise Demar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collection 13

EARLY EUROPEAN BOOKS Explore the Record of European Life and Culture About Collection 13 Early European Books Collection 13 presents a selection themed around literature, poetry and drama. Items from London’s Wellcome Library, Florence’s Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Copenhagen’s Kongelige Bibliotek and The Hague’s Koninklijke Bibliotheek provide a rich assembly of content from across Europe. Supported by key classical and medieval texts, at the heart of Collection 13 is a body of works which document the remarkable flowering of vernacular literatures witnessed during the early modern period. Among the thousands of titles featured are acknowledged literary landmarks, but also less familiar items. Brought together, Collection 13 builds up a picture of the early modern literary scene that embraces ephemeral as well as timeless works, and that strongly accentuates its creative diversity. Collection 13 comes complete with USTC subject classifications to enable and enhance user experience. From Homer to Persius The early modern period was defined by its rediscovery of classical texts, and Collection 13 presents a choice of these ranging from literary giants like Homer and Ovid to more minor figures like Persius (34-62 CE) and Claudian (c.370-c.404 CE). Prose pieces include a 1624 Amsterdam edition of Apuleius (c.124-c.170 CE) which includes his Erasmus (1466-1536) and Philip Melanchthon (1497-1560). Metamorphoses or The Golden Ass, while a 1700 edition of Other Erasmus items include a 1524 edition of Euripides Petronius’ notorious Satyricon is another bawdy inclusion. in Greek and Latin, and a 1507 Aldine printing of the same Classical literature’s rediscovery inevitably involved its Latin translation bound with his own classical imitation, reconstruction, and items featured reflect both advances Ode de laudibus Britanniæ. -

The Recollections of Encolpius

The Recollections of Encolpius ANCIENT NARRATIVE Supplementum 2 Editorial Board Maaike Zimmerman, University of Groningen Gareth Schmeling, University of Florida, Gainesville Heinz Hofmann, Universität Tübingen Stephen Harrison, Corpus Christi College, Oxford Costas Panayotakis (review editor), University of Glasgow Advisory Board Jean Alvares, Montclair State University Alain Billault, Université Jean Moulin, Lyon III Ewen Bowie, Corpus Christi College, Oxford Jan Bremmer, University of Groningen Ken Dowden, University of Birmingham Ben Hijmans, Emeritus of Classics, University of Groningen Ronald Hock, University of Southern California, Los Angeles Niklas Holzberg, Universität München Irene de Jong, University of Amsterdam Bernhard Kytzler, University of Natal, Durban John Morgan, University of Wales, Swansea Ruurd Nauta, University of Groningen Rudi van der Paardt, University of Leiden Costas Panayotakis, University of Glasgow Stelios Panayotakis, University of Groningen Judith Perkins, Saint Joseph College, West Hartford Bryan Reardon, Professor Emeritus of Classics, University of California, Irvine James Tatum, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire Alfons Wouters, University of Leuven Subscriptions Barkhuis Publishing Zuurstukken 37 9761 KP Eelde the Netherlands Tel. +31 50 3080936 Fax +31 50 3080934 [email protected] www.ancientnarrative.com The Recollections of Encolpius The Satyrica of Petronius as Milesian Fiction Gottskálk Jensson BARKHUIS PUBLISHING & GRONINGEN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY GRONINGEN 2004 Bókin er tileinkuð -

Orthographies in Grammar Books

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 30 July 2018 doi:10.20944/preprints201807.0565.v1 Tomislav Stojanov, [email protected], [email protected] Institute of Croatian Language and Linguistic Republike Austrije 16, 10.000 Zagreb, Croatia Orthographies in Grammar Books – Antiquity and Humanism Summary This paper researches the as yet unstudied topic of orthographic content in antique, medieval, and Renaissance grammar books in European languages, as part of a wider research of the origin of orthographic standards in European languages. As a central place for teachings about language, grammar books contained orthographic instructions from the very beginning, and such practice continued also in later periods. Understanding the function, content, and orthographic forms in the past provides for a better description of the nature of the orthographic standard in the present. The evolution of grammatographic practice clearly shows the continuity of development of orthographic content from a constituent of grammar studies through the littera unit gradually to an independent unit, then into annexed orthographic sections, and later into separate orthographic manuals. 5 antique, 22 Latin, and 17 vernacular grammars were analyzed, describing 19 European languages. The research methodology is based on distinguishing orthographic content in the narrower sense (grapheme to meaning) from the broader sense (grapheme to phoneme). In this way, the function of orthographic description was established separately from the study of spelling. As for the traditional description of orthographic content in the broader sense in old grammar books, it is shown that orthographic content can also be studied within the grammatographic framework of a specific period, similar to the description of morphology or syntax. -

Further Commentary Notes

Virgil Aeneid X Further Commentary Notes Servius, the author of a fourth-century CE commentary on Virgil is mentioned several times. Servius based his notes extensively on the lost commentary composed earlier in the century by Aelius Donatus. A version of Servius, amplified by material apparently taken straight from Donatus, was compiled later, probably in the seventh or eighth century. It was published in 1600 by Pierre Daniel and is variously referred to as Servius Auctus, Servius Danielis, or DServius. Cross-reference may be made to language notes – these are in the printed book. An asterisk against a word means that it is a term explained in ‘Introduction, Style’ in the printed book. A tilde means that the term is explained in ‘Introduction, Metre’ in the printed book. 215 – 6 In epic, descriptions of the time of day, particularly dawn, call forth sometimes surprising poetic flights. In Homer these are recycled as formulae; not so in Virgil (for the most part), although here he is adapting a passage from an earlier first- century epic poet Egnatius, from whose depiction of dawn seems to come the phrase curru noctivago (cited in Macrobius, Sat. 6.5.12). This is the middle of the night following Aeneas’s trip to Caere. The chronology of Books VIII – X is as follows: TWO DAYS AGO Aeneas sails up the Tiber to Evander (VIII). NIGHT BEFORE Aeneas with Evander. Venus and Vulcan (VIII). Nisus and Euryalus (IX). DAY BEFORE Evander sends Aeneas on to Caere; Aneneas receives his armour (VIII). Turnus attacks the Trojan camp (IX, X). -

![Catullum Numquam Antea Lectum […] Lego »: a Short Analysis of Catullus’ Fortune in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9516/catullum-numquam-antea-lectum-lego-%C2%BB-a-short-analysis-of-catullus-fortune-in-the-sixteenth-and-seventeenth-centuries-949516.webp)

Catullum Numquam Antea Lectum […] Lego »: a Short Analysis of Catullus’ Fortune in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries

chapter 15 « Catullum Numquam Antea Lectum […] Lego »: A Short Analysis of Catullus’ Fortune in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries Alina Laura de Luca The Liber Catulli Veronensis has a mysterious history full of twists and turns, chance discoveries and sudden disappearances, avid attempts at correction and of convictions for obscenity. We know that it had an enormous and imme- diate popularity among poets of the ‘Golden Age’ and was read and discussed from the second to the fourth century.1 However, the study and discussion of Catullus in the Middle Ages have left only a few traces. He is mentioned two or three times and he is not listed in the manuscript catalogues of monastic libraries during the Carolingian age; whereas in the same period we witness a multiplication of copies of Horace, Virgil, Ovid, and Juvenal. Nevertheless, there is evidence that Catullus was being read in France and northern Italy: in the late ninth century poem 62 was included in a florilegium;2 in 966 Raterio, Bishop of Verona, was reading Catullus, as he says in one of his sermons: “I read Catullus that has never been accessed before”.3 However, the Liber soon disap- peared, or more probably it lay undisturbed in the Chapter Library of Verona throughout most of the Middle Ages.4 1 The modern study of Kenneth Quinn, The Catullan revolution (Melbourne, Melbourne University Press, 1959), describes the impact that Catullus had on Roman poetry. Individual Catullan poems were admired and imitated by the Augustan poets, above all by elegists, and his popularity continued later with Martial, Pliny the Younger, Aulus Gellius and Pomponius. -

Rhetorical and Dramatic Performance in Donatus' Commentary On

chapter 10 From the Stage to the Court: Rhetorical and Dramatic Performance in Donatus’ Commentary on Terence Beatrice da Vela Aelius Donatus’ Commentary on Terence (4th cent. ad) is the most complete late antique exegesis of Terence’s plays, commenting on five of them (Andria, Eunuchus, Adelphoe, Hecyra, Phormio) in full.1 Scholars have often used this work to shed light on Terence’s words and lines which are not sufficiently clear, or to reconstruct extra-textual features (particularly concerning delivery and performance). Besides commenting on Terence’s language and explain- ing the meaning of obscure references in the text (in a way which is very similar to another great late-antique commentary, that of Servius on Vergil), Aelius Donatus is particularly interested in performative elements, especially the different uses of the voice and the gestures of different parts of the body (primarily hands and face).2 The grammarian is able to describe extra-textual features of Terence’s text in detail, showing awareness of and sensibility to the peculiarity of drama as a genre.3 What remains to be determined is the 1 From now on, texts from the Donatus’ Commentary on Terence will be indicated by the abbre- viation Don., followed by the abbreviation for the name of Terence’s play (e.g. Don. Ad. shall be interpreted as Donatus’ commentary on Terence’s Adelphoe). To avoid ambiguity, each time Terence’s text is quoted, the abbreviation of the play is preceded by the abbreviation of the author (e.g. Ter. Ad.). 2 An example of a note on delivery: Don. -

University of Groningen a Cultural History of Gesture Bremmer, JN

University of Groningen A Cultural History Of Gesture Bremmer, J.N.; Roodenburg, H. IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 1991 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Bremmer, J. N., & Roodenburg, H. (1991). A Cultural History Of Gesture. s.n. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 24-09-2021 Gestures and conventions: the gestures of Roman actors and orators FRITZ GRAF We all gesticulate - that is, accompany our speech by more or less elaborate movements of arms, hands, and fingers. Northerners gesticulate less, the stereotype says, Mediterranean people more; in 1832, the learned author of a book on Neapolitan gestures (see Thomas, p. 3 of this volume) even asserted that among the inhabitants of northern Europe (that is, presumably, all of Europe north of the Alps) gesticulation did not exist - the cold climate having made them less fiery than the Italians.' This exaggerated opinion shows how gesticulation is generally viewed - as something natural and spontaneous, dependent upon factors of climate or character. -

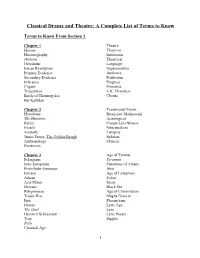

A Complete List of Terms to Know

Classical Drama and Theatre: A Complete List of Terms to Know Terms to Know From Section 1: Chapter 1 Theatre History Theatron Historiography Institution Historia Theatrical Herodotus Language Ionian Revolution Impersonation Primary Evidence Audience Secondary Evidence Positivism Inference Progress Cogent Primitive Tripartition E.K. Chambers Battle of Thermopylae Chorus Ibn Kahldun Chapter 2 Transitional Forms Herodotus Bronislaw Malinowski The Histories Aetiological Relics Claude Levi-Strauss Fossils Structuralism Aristotle Lumpers James Frazer, The Golden Bough Splitters Anthropology Mimetic Positivism Chapter 3 Age of Tyrants Pelasgians Tyrannos Indo-Europeans Pisistratus of Athens Proto-Indo-European Attic Ionians Age of Lawgivers Athens Solon Asia Minor Sicily Dorians Black Sea Peloponnese Age of Colonization Trojan War Magna Graecia Epic Phoenicians Homer Lyric Age The Iliad Lyre Heinrich Schliemann Lyric Poetry Troy Sappho Polis Classical Age 1 Chapter 4.1 City Dionysia Thespis Ecstasy Tragoidia "Nothing To Do With Dionysus" Aristotle Year-Spirit The Poetics William Ridgeway Dithyramb Tomb-Theory Bacchylides Hero-Cult Theory Trialogue Gerald Else Dionysus Chapter 4.2 Niches Paleontologists Fitness Charles Darwin Nautilus/Nautiloids Transitional Forms Cultural Darwinism Gradualism Pisistratus Steven Jay Gould City Dionysia Punctuated Equilibrium Annual Trading Season Terms to Know From Section 2: Chapter 5 Sparta Pisistratus Peloponnesian War Athens Post-Classical Age Classical Age Macedon(ia) Persian Wars Barbarian Pericles Philip -

Articulus Postprint

1 The articulus according to Latin grammarians up to the early Middle Ages: The complex interplay of tradition and innovation in grammatical doctrine 1 By TIM DENECKER , Leuven–Gent / PIERRE SWIGGERS , Leuven Abstract: Ancient Greek grammar, and in particular its parts-of-speech system, provided the conceptual and terminological basis for the description of the Latin language. This transfer caused a number of (sub)categorial “frictions”, due to the structural differences that exist between both languages. A specific instance is that of the article, ἄρθρον or articulus , which was considered (part of) a separate part of speech in Greek, but which is absent from Latin. In this paper we discuss the views and comments expressed on this issue by Latin grammarians up to the early Middle Ages. While some of the grammarians deny that there is an article in Latin, others state that it does exist, but that it does not “count” as a separate part of speech, or that it is “substituted for” with the demonstrative pronoun. Their comments are illustrative (a) of the various adaptive strategies followed in the “bargaining situation” constituted by the projection of the Greek parts-of-speech system upon the Latin language; (b) of transformations undergone by the Graeco-Latin grammatical legacy in late antiquity and the early Middle Ages; and (c) of a push chain of changes in the anaphoric-deictic (sub)system of Latin pronouns. In a study on the treatment of nominal gender in Latin grammars of Antiquity, Jaana Vaahtera makes the following observation: Romans writing on language frequently note that there is no article in Latin (e.g. -

Controversial Topics in Literature and Education: Hrotswitha and Donatus on Terence’S Rapes,” JOLCEL 3 (2020): 2–22

C C Chrysanthi Demetriou, “Controversial Topics in Literature and Education: Hrotswitha and Donatus on Terence’s Rapes,” JOLCEL 3 (2020): 2–22. DOI: ⒑21825/jolcel.vi⒊825⒈ * N This contribution is part of a larger dialogue of three articles and one responding piece that form the current issue of JOLCEL. The other contributions are “The Meaning and Use of fabula in the Dialogus creaturarum moralizatus” by Brian Møller Jensen (pp. 24–41) and “Introite, pueri! The School-Room Performance of George Buchanan’s Latin Medea in Bordeaux” by Lucy C.M.M. Jackson (pp. 43–61). The response piece is “Latin Education and Classical Reception: the Minor Genres” by Rita Copeland (pp. 62–66). * Controversial Topics in Literature and Education: Hrotswitha and Donatus on Terence’s Rapes* C D Open University of Cyprus A The paper examines the way Terence’s comedy was received and exploited by the dramas of Hrotswitha of Gandersheim. The discussion focuses on a particular comic motif: rape. Aer the examination of the way Hrotswitha transforms Terentian rapes and incorporates them into her dramatic composition, the paper focuses on a very important spectrum of Terence’s survival: education. Specifically, it explores how rape was read and interpreted by the most important treatise of Terence’s exegesis: the commentary of Donatus. All in all, the paper aims at identiing possible common approaches between the educational and literary sources under examination, while, at the same time, investigates the extent to which the educational context of Terence’s reception affected the literary products that used Terence as their prototype. -

The Platonic Significance of the Ivory Gate in Book 6 of Aeneid

Falsa Insomnia: The Platonic Significance of the Ivory Gate in Book VI of the Aeneid Taylor Marshall May 7, 2009 IPS 8311 Homer and Vergil As Dante’s Vergil leads his pilgrim past the gates of Hell, the narrator recounts how, “with gladness in his face, [Virgil] placed his hand upon my own, to comfort me, he drew me in among the hidden things.”1 For Dante and those before him, Vergil’s prophetic powers and detailed depiction the of netherworld indicated that he in fact possessed access to occult knowledge. Vergil’s reputation as a prophet derives in part no doubt from the Messianic prophecy of his fourth Eclogue.2 Other mystical practices, such as the sortes Vergilianae whereby devotees randomly chose passages from the Aeneid as a form of divination, arose from the conviction that Vergil possessed prophetic insight. The depiction of Vergil as a seer of Apollo no doubt stems from Vergil’s resurrection of the concept of the vates as a poetic soothsayer.3 Vergil’s provocative account of the ascent of Aeneas from Hades in the final lines of the sixth book is yet another passage that invites speculation over Vergil’s message and intent. At the end of Book Six, Vergil describes the two gates of sleep in the netherworld (6.893-8). One is the gate of horn through which verae umbrae, true shades, ascend to the realm of the living. The other is the gate of ivory through which the souls of the departed send falsa insomnia into the world of the living. -

Suetoniusâ•Ž Life of Vergil: Text, Commentary, and Analysis Of

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Classics Honors Papers Classics Department 2019 Suetonius’ Life of Vergil: Text, Commentary, and Analysis of Authorship Bailey Mertz Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/classicshp Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Mertz, Bailey, "Suetonius’ Life of Vergil: Text, Commentary, and Analysis of Authorship" (2019). Classics Honors Papers. 5. https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/classicshp/5 This Honors Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics Department at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classics Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. Suetonius’ Life of Vergil: Text, Commentary, and Analysis of Authorship Honors Thesis Presented by Bailey Elizabeth Mertz To The Department of Classics Advised by Professor Darryl Phillips Read by Professor Abbe Walker Connecticut College New London, Connecticut May 1, 2019 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Commentary and Vocabulary list for Vita Vergili 9 English translation of Vita Vergili 60 Appendix: Authorship and Attribution of Vita Vergili 68 Bibliography 85 2 Introduction Vergil and the Life of Vergil The text of the Life of Vergil presented here comes from J.C. Rolfe’s edition of Suetonius (Vol. II) published in the Loeb Classical Library. Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus’ Vita Vergili presents a biography of the poet Vergil (70 BCE – 19 BCE), including details about his personal life, his possessions, and his literary works.