Media Clips Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record—Senate S6930

S6930 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE October 31, 2017 MERKLEY, Mr. TILLIS, Mr. KING, Mr. and contributions of Native Americans and the Providence Park venue with spirit and FRANKEN, Mr. ROUNDS, Mr. TESTER, Ms. their ancestors: Now, therefore, be it pride, are the best fans in the NWSL; STABENOW, and Mr. HEINRICH) sub- Resolved, That the Senate— Whereas the Portland Thorns FC holds the mitted the following resolution; which (1) recognizes the month of November 2017 record for highest average game attendance as ‘‘National Native American Heritage was considered and agreed to: in the NWSL in 2017 and has held that record Month’’; in each year since the establishment of the S. RES. 316 (2) recognizes the Friday after Thanks- NWSL in 2013; Whereas, from November 1, 2017, through giving as ‘‘Native American Heritage Day’’ Whereas the goalkeeper of the Portland November 30, 2017, the United States cele- in accordance with section 2(10) of the Native Thorns FC, Adrianna Franch, was named the brates National Native American Heritage American Heritage Day Act of 2009 (Public NWSL Goalkeeper of the Year for 2017; Month; Law 111–33; 123 Stat. 1923); and Whereas the Portland Thorns FC adopted Whereas National Native American Herit- (3) urges the people of the United States to the official State motto of Oregon, ‘‘Alis age Month is an opportunity to consider and observe National Native American Heritage Volat Propriis’’, meaning ‘‘She Flies with recognize the contributions of Native Ameri- Month and Native American Heritage Day Her Own Wings’’, to capture the independent cans to the history of the United States; with appropriate programs and activities. -

Senate Floor

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 163 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, OCTOBER 31, 2017 No. 176 Senate The Senate met at 10 a.m. and was As I said last week, no single bill or As government officials review this called to order by the President pro program is going to solve this crisis on morning’s report and as agencies de- tempore (Mr. HATCH). its own. Only a sustained, committed velop new plans to fulfill its objectives, f effort can do that. That has been my I will continue to work with partners view over the many years that I have in Washington and Kentucky to ad- PRAYER been involved in this issue, from the dress this important crisis. The goal, of The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- first time I invited the White House course, is that one day we can finally fered the following prayer: drug czar down to Eastern Kentucky to put the pain of opioid abuse behind us Let us pray. see the challenges posed by prescrip- once and for all. Sovereign Lord of the Universe, we tion drug abuse firsthand to my work f pray today for all who govern. Use our on other initiatives, such as helping JUDICIAL NOMINATIONS Senators for Your glory, providing pass a law to help address the tragedy them with wisdom to live with the in- of babies born addicted to drugs. Mr. MCCONNELL. Mr. President, yes- tegrity that brings stability to nations. -

Major League Soccer/Triple-A Baseball Task Force Report and Recommendations Background: Summary of Initial Proposal

Major League Soccer/Triple-A Baseball Task Force Report and Recommendations March 2009 Background: For the past couple years, Major League Soccer (MLS) has been in an expansion mode. MLS returned to San Jose in 2008. Seattle was awarded the 15th team franchise in early 2008 and will begin play this year. Also in 2008, MLS awarded the 16 th franchise to Chester, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Philadelphia. The Chester team will start play in 2010. In the spring of 2008, MLS announced that it intended to take proposals for two additional expansion franchises which would begin play in 2011. Merritt Paulson, the owner of the Portland Timbers and Portland Beavers, approached the City and indicated he wanted to submit a proposal to MLS for one of the available expansion franchises. The franchise fee paid to MLS for an expansion team has increased dramatically during the recent expansion period. The Toronto team began play in 2007 and paid a fee of $10 million. The next year, the San Jose team began play and paid a fee of $20 million. In 2008, Seattle and Chester paid $30 million for their expansion teams. The announced fee for the two franchises to be awarded in 2009 is $40 million. Shortstop LLC is the name of the business entity formed by Mr. Paulson for the operation of the teams. The current Portland Timbers are a First Division team in the United Soccer League. This league shares an affiliation with Major League Soccer (MLS) and with the international soccer governing body FIFA. MLS is the highest level of competitive soccer played in the United States. -

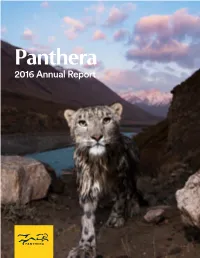

2016 Annual Report

Panthera 2016 Annual Report 2016 ANNUAL REPORT — 1 “I COULD HARDLY BELIEVE MY EYES” Our cover image captures the moment after a snow leopard crossed the freezing Uchkul River in Sarychat- Ertash State Nature Reserve in eastern Kyrgyzstan. The photographer, Sebastian Kennerknecht, had hiked for miles in the thin mountain air looking for spots to place camera traps—and when he retrieved this image, he could hardly believe his eyes. “A gorgeous snow leopard, dripping wet in front of a sunrise-lit alpine sky, was staring straight at me,” he said. “I was so grateful that this cat allowed us a glimpse into its otherwise secretive life. “As a wildlife photographer,” he continued, “this image is incredibly special to me, but as a conservationist, it’s important to appreciate why it can exist in the first place. Panthera’s actions in Kyrgyzstan … are major reasons snow leopards still inhabit this part of central Asia. Their work is critical, and I am proud to be able to support it through my photography.” 2 — 2016 ANNUAL REPORT Panthera 2016 Annual Report 2016 ANNUAL REPORT — 1 2 — 2016 ANNUAL REPORT A cheetah cub in the Arusha Region of Tanzania Contents 03 04 06 08 Panthera's A Message from A Decade of A Message from Mission the Chairman Saving Big Cats the CEO 09 32 34 36 Program The Science of Artistic Allies in Changing the Highlights Saving Cats Cat Conservation Game 37 38 42 45 2016 Financial Board, Staff, and 2016 Scientific Investing Summary Council Listings Publications in Landscapes 2016 ANNUAL REPORT — 3 4 — 2016 ANNUAL REPORT A young jaguar in Emas National Park in the Brazilian Cerrado Panthera's Mission Panthera’s mission is to ensure a future for wild cats and the vast landscapes on which they depend. -

Major League Soccer Owners Major League Soccer Owners Own a Share in the League and Have the Right to Operate a Team

Major League Soccer owners Major League Soccer owners own a share in the league and have the right to operate a team. Major League Soccer operates under a single-entity structure in which teams and player contracts are centrally owned by the league. Each Major League Soccer team has an investor-operator that is a shareholder in the league. In order to control costs, the league shares revenues and holds player List of MLS owners Atlanta United FC Arthur Blank – (2014–present) Chicago Fire Anschutz Entertainment Group – (1997–2007) Andrew Hauptman (Andell Holdings) – (2007–present) Colorado Rapids Anschutz Entertainment Group – (1995–2003) Kroenke Sports & Entertainment – (2003–present) Columbus Crew Lamar Hunt – (1995–2006) Clark Hunt – (2006–2013) Anthony Precourt (Precourt Sports Ventures LLC) – (2013–present) D.C. United Washington Soccer, LP – (1995–2000) Anschutz Entertainment Group – (2001–2006) William Chang (D.C. United Holdings) – (2006–2012) William Chang, Erick Thohir and Jason Levien – (2012–2018) Patrick Soon-Shiong, Jason Levien and Steven Kaplan (investor) – (2018–present) FC Dallas Major League Soccer – (1995–2001) Lamar Hunt – (2001–2006) Clark Hunt – (2006–present) Houston Dynamo Anschutz Entertainment Group – (2005–2008) Anschutz Entertainment Group, Oscar De La Hoya and Gabriel Brener – (2008–2015) Gabriel Brener, Oscar De La Hoya, Jake Silverstein, Ben Guill – (2015–present) LA Galaxy L.A. Soccer Partners, LP – (1995–1997) Anschutz Entertainment Group – (1998–present) Los Angeles FC Peter Guber (Executive Chairman), -

Marketing of Professional Women's Soccer in the United States

MARKETING OF PROFESSIONAL WOMEN’S SOCCER IN THE UNITED STATES THROUGH FEMINIST THEORIES by CHRISTOPHER HENDERSON (Under the Direction of James J. Zhang) ABSTRACT Despite the success of the United States Women’s National Team (USWNT), two women’s soccer leagues have quickly failed in the U.S. This doctoral dissertation examines the past and present of the marketing of professional women’s soccer in the United States emphasizing feminist themes to fulfill three objectives: (a) to critically examine the history of the marketing of women’s soccer in the United States to identify and gain a better comprehension of changes in theory and practice of marketing in women’s soccer in the U.S. over time; (b) to identify and explain the use of three feminist themes in the marketing of women’s soccer, specifically in the NWSL; and (c) to analyze the impact of these three feminist themes on the related marketing strategies used within in the NWSL in an effort to build a framework while also developing recommendations for marketing practitioners for the promotion and marketing of professional women’s soccer in the United States. The historical analysis segment revealed that the failure of the first two professional women’s soccer leagues in the United States were largely a result of poor resource allocation and an inability to connect with and retain fans, the media, and sponsors. The Women’s United Soccer Association (WUSA) burned through capital at an unsustainable rate and was unable to maintain the excitement of the 1999 Women’s World Cup, leading to microscopic television ratings and perennially falling attendance. -

The Oregonian Providence Park's History Once Included Dreams of 100,000 Seats

The Oregonian Providence Park's history once included dreams of 100,000 seats By John Killen May 9, 2017 When news broke that the Portland Timbers were making plans to expand Providence Park to 25,000 seats, most fans of the city's Major League Soccer team were probably thrilled. The proposal, which goes before the City Council this week, would raise the stadium's capacity by 4,000. If the plan makes it over various regulatory hurdles, the addition is sure to help raise the roar of the team's enthusiastic fans when the Timbers and the Portland Thorns play their home games. But it might surprise many to learn that the stadium still would seat 10,000 fewer than it once did. As far back as the 1930s, the venue held up to 35,000. The stadium evolved much like the city around it – in fits and starts, adjusting for dog racing, baseball and now soccer as interests changed over the years. The genesis of what is now Providence Park goes back to the 1890s, when the site was an athletic field for the fledgling Multnomah Amateur Athletic Club, today known as the Multnomah Athletic Club. The club was looking for a place to hold athletic events, and it leased a sunken field just south of the Portland Exposition Center, a massive brick-facade building near what is now the corner of West Burnside and 19th Avenue. The area had once been home to vegetable gardens cultivated by Chinese immigrants who lived in the Goose Hollow area, along Tanner Creek. -

Sweepstakes Official Rules

Bloodworks Save More Lives Sweepstakes 2021 – Enter to Win Sports Memorabilia and Prizes Bloodworks Official Rules NO PAYMENT OR PURCHASE OF ANY KIND IS NECESSARY TO ENTER OR WIN. A PAYMENT OR PURCHASE WILL NOT INCREASE YOUR CHANCE OF WINNING. VOID WHERE PROHIBITED. The Bloodworks Save More Lives Sweepstakes 2021 (“Sweepstakes”) is a promotional giveaway designed to encourage Donors to register with Bloodworks for donations and to promote Bloodworks. The Sweepstakes are sponsored exclusively by Bloodworks (“Sponsor” or “Bloodworks”) with the principal place of the organization located at 921 Terry Avenue, Seattle, WA 98104. Sponsor will randomly select winners as defined herein and prizes as defined herein will be awarded in accordance with these Official Rules (“Official Rules”). For the avoidance of doubt, the Seattle Sounders FC, Adrian Hanauer, Paul G Allen Trust, Drew Carey, Peter Tomozawa, Tod and Tara Leiweke, Roger Levesque, Mariners Baseball Club of Seattle, LP, John Stanton, Nintendo of America, Dan Wilson, Jordan Babineaux, DK Metcalf, Seattle Seahawks, Russell Wilson, Keegan Hall, Kyle Seager, Ken Griffey Jr., Edgar Martinez, Breanna Stewart, Seattle Storm, Force 10 Hoops, Seattle Seawolves Rugby Club, Adrian Balfour, Shane Skinner, Mat Turner, Portland Timbers, Peregrine Sports, Merritt Paulson, National Football League, National League of Professional Baseball Clubs, Women's National Basketball Association, Major League Soccer, American professional Rugby, and the respective affiliates of the aforementioned entities and individuals, are neither participants in nor sponsors of the Save More Lives Sweepstakes 2021. 1. Eligibility: In order to be eligible to participate in the Sweepstakes one must agree to be bound by these Official rules which constitute a binding agreement. -

Major League Soccer Case Study an Examination Into the Future of the League

Syracuse University SURFACE Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects Projects Spring 5-1-2013 Major League Soccer Case Study An Examination into the Future of the League Matt Samost Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, and the Sports Management Commons Recommended Citation Samost, Matt, "Major League Soccer Case Study An Examination into the Future of the League" (2013). Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects. 94. https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone/94 This Honors Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Major League Soccer Case Study An Examination into the Future of the League Honors Advisor: . Honors Reader: . Matt Samost SPM 499 Honors Capstone Fall 2012 Abstract Major League Soccer has grown tremendously since its inception in 1996. The league, however, still is a work in progress. The overarching question of this case study deals with an examination into the future of the league. Will it continue to be a niche sport on the American sports landscape or will it challenge the big four leagues in the years to come? Broken into five subtopics, the case study looks to address this question by examining the league through multiple lenses in order to be able to take both an in-depth and wide look at the current condition of the league. -

OREGON Annual Report 2017 3 3

OREGON Annual Report 2017 DEAR FRIENDS NATURE PROVIDES. We envision a world where the diversity of life thrives and people act to conserve nature, both for its own sake WE PROTECT. and its ability to meet our needs and enrich our lives. Using science as our guide, The Nature Conservancy has recently evaluated where we are able SUSTAINABLE FOOD HEALTHY COMMUNITIES CLEAN, RELIABLE WATER to make the most impact on this vision “As a fourth-generation rancher, I’m working with “For the last 10 years, our construction “Our city is surrounded by forests; it’s one reason people in the years to come. The result is a global Shared Conservation my children on the same land my great-grandparents company has solely focused on specialized love living and visiting here. But these forests are also Agenda, which focuses our work on the following five priorities in homesteaded in 1884. We’re proving with our actions restoration projects, and we’re honored to at risk of wildfire that could harm both our city and The Nature Conservancy that our cattle management practices are a critical have led the floodplain restoration work at our drinking water supply. We take that risk seriously, the United States and the 70 countries in which we currently work. in Oregon component to the conservation efforts in our riparian the Conservancy’s Willamette Confluence which has led us to a long-term, nationally recognized and upland habitats. We’re doing this in a way that Preserve. It was an incredible project, and stewardship partnership with The Nature Conservancy, OFFICERS & EXECUTIVE Protecting land and water. -

Soccer Leagues

SOCCER LEAGUES {Appendix 5, to Sports Facility Reports, Volume 12} Research completed as of July 20, 2011 MAJOR INDOOR SOCCER LEAGUE (MISL) Team: Baltimore Blast Principal Owner: Edwin F. Hale, Sr. Current Value ($/Mil): N/A Team Website Stadium: 1st Mariner Arena Date Built: 1962 Facility Cost ($/Mil): N/A Facility Financing: N/A Facility Website UPDATE: The City of Baltimore is looking to start a private-public partnership for a new arena to replace the aging 1st Mariner Arena, which will cost around $300 million. NAMING RIGHTS: Baltimore Blast owner and 1st Mariner Bank President and CEO Ed Hale acquired the naming rights to the arena through his company Arena Ventures, LLC as a result of a national competitive bidding process conducted by the City of Baltimore. Arena Ventures agreed to pay the City $75,000 annually for 10 years for the naming rights starting in 2003. Team: Chicago Riot Principal Owner: Peter Wilt Current Value ($/Mil): N/A Team Website Stadium: Odeum Sports and Expo Center Date Built: 1981 Facility Cost ($/Mil): N/A Facility Financing: N/A © Copyright 2011, National Sports Law Institute of Marquette University Law School Page 1 Facility Website UPDATE: The Riot played in the MISL league for the first time in the 2010-11 season. The Odeum Sports and Expo Center is 130,000 square feet with 3 complete all turf playing fields, eight locker rooms with complete shower facilities, a seating capacity of 3,500, parking for 2,000 vehicles on site, and full service food and beverage facilities. NAMING RIGHTS: N/A Team: Milwaukee Wave Principal Owner: Jim Lindenberg Current Value ($/Mil): N/A Team Website Stadium: U.S. -

SAN ANTONIO FC 2018 San Antonio FC Table of Contents

1 SAN ANTONIO FC 2018 San Antonio FC Table of Contents General Information .................................................................... 4 Career Records ......................................................................... 104 2018 Schedule ............................................................................... 5 Career Hat Trick, Clean Sheets, Penalties ........................ 105 2018 Roster ..................................................................................... 6 Opponent HT, CS, Penalties ................................................. 106 Pronunciation Guide ................................................................... 7 Rookie Single-Game Records ............................................. 107 Rookie Season Records ......................................................... 108 Players ..........................................................................8-53 Miscellaneous Records.......................................................... 109 0-Matthew Cardone ............................................................... 9-10 Toyota Field Records .............................................................. 110 1-Lee Johnston ........................................................................ 11-12 Attendance Records............................................................... 111 2-Darnell King .......................................................................... 13-14 3-Ryan Felix ............................................................................... 15-16 U.S.