The Oregonian Providence Park's History Once Included Dreams of 100,000 Seats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record—Senate S6930

S6930 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE October 31, 2017 MERKLEY, Mr. TILLIS, Mr. KING, Mr. and contributions of Native Americans and the Providence Park venue with spirit and FRANKEN, Mr. ROUNDS, Mr. TESTER, Ms. their ancestors: Now, therefore, be it pride, are the best fans in the NWSL; STABENOW, and Mr. HEINRICH) sub- Resolved, That the Senate— Whereas the Portland Thorns FC holds the mitted the following resolution; which (1) recognizes the month of November 2017 record for highest average game attendance as ‘‘National Native American Heritage was considered and agreed to: in the NWSL in 2017 and has held that record Month’’; in each year since the establishment of the S. RES. 316 (2) recognizes the Friday after Thanks- NWSL in 2013; Whereas, from November 1, 2017, through giving as ‘‘Native American Heritage Day’’ Whereas the goalkeeper of the Portland November 30, 2017, the United States cele- in accordance with section 2(10) of the Native Thorns FC, Adrianna Franch, was named the brates National Native American Heritage American Heritage Day Act of 2009 (Public NWSL Goalkeeper of the Year for 2017; Month; Law 111–33; 123 Stat. 1923); and Whereas the Portland Thorns FC adopted Whereas National Native American Herit- (3) urges the people of the United States to the official State motto of Oregon, ‘‘Alis age Month is an opportunity to consider and observe National Native American Heritage Volat Propriis’’, meaning ‘‘She Flies with recognize the contributions of Native Ameri- Month and Native American Heritage Day Her Own Wings’’, to capture the independent cans to the history of the United States; with appropriate programs and activities. -

Major League Soccer Atlanta United Vs Philadelphia Union Reddit Live

major league soccer atlanta united vs philadelphia union reddit : liveStream, time GO LIVE http://nufilm.live/event/major-league-soccer-atlanta-united-vs-philadelphia-union-reddit CLICK HERE GO LIVE http://nufilm.live/event/major-league-soccer-atlanta-united-vs-philadelphia-union-reddit 75 votes, 850 comments. FT: Atlanta United FC 2-0 Philadelphia Union Atlanta United FC scorers: Julian Gressel (10'), Josef Martínez (80') Venue … 19' Haris Medunjanin (Philadelphia Union) is shown the yellow card. 19' Second yellow card to Haris Medunjanin (Philadelphia Union). 21' Goal! Atlanta United FC 1, Philadelphia Union 0. Josef Martínez (Atlanta United FC) converts the penalty with a right footed shot to the top left corner. 23' Substitution, Philadelphia Union. Warren Creavalle Atlanta United FC 1, Philadelphia Union 0. Julian Gressel (Atlanta United FC) right footed shot from the centre of the box to the bottom right corner. Assisted by Leandro González Pirez. 33' Goal! Atlanta United FC 2, Philadelphia Union 0. Josef Martínez (Atlanta United FC) left footed shot from the left side of the box to the bottom right Find Atlanta United vs Philadelphia Union result on Yahoo Sports. View full match commentary including video highlights, news, team line-ups, player ratings, stats and more. Major League Soccer 2021 Table. Philadelphia Union are in the 3rd position of Major League Soccer and they are in contention for Final Series Play-offs. Atlanta United are in the 10th position of Major League Soccer. Eastern Conference # Philadelphia have kept a clean sheet in their last 3 away matches (Major League Soccer). Philadelphia win or draw 1.57 Philadelphia win or draw 1.57 Atlanta United is playing against Philadelphia Union in the USA Major League Soccer. -

MLS Game Guide

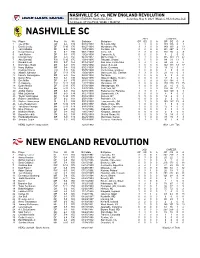

NASHVILLE SC vs. NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION NISSAN STADIUM, Nashville, Tenn. Saturday, May 8, 2021 (Week 4, MLS Game #44) 12:30 p.m. CT (MyTV30; WSBK / MyRITV) NASHVILLE SC 2021 CAREER No. Player Pos Ht Wt Birthdate Birthplace GP GS G A GP GS G A 1 Joe Willis GK 6-5 189 08/10/1988 St. Louis, MO 3 3 0 0 139 136 0 1 2 Daniel Lovitz DF 5-10 170 08/27/1991 Wyndmoor, PA 3 3 0 0 149 113 2 13 3 Jalil Anibaba DF 6-0 185 10/19/1988 Fontana, CA 0 0 0 0 231 207 6 14 4 David Romney DF 6-2 190 06/12/1993 Irvine, CA 3 3 0 0 110 95 4 8 5 Jack Maher DF 6-3 175 10/28/1999 Caseyville, IL 0 0 0 0 3 2 0 0 6 Dax McCarty MF 5-9 150 04/30/1987 Winter Park, FL 3 3 0 0 385 353 21 62 7 Abu Danladi FW 5-10 170 10/18/1995 Takoradi, Ghana 0 0 0 0 84 31 13 7 8 Randall Leal FW 5-7 163 01/14/1997 San Jose, Costa Rica 3 3 1 2 24 22 4 6 9 Dominique Badji MF 6-0 170 10/16/1992 Dakar, Senegal 1 0 0 0 142 113 33 17 10 Hany Mukhtar MF 5-8 159 03/21/1995 Berlin, Germany 3 3 1 0 18 16 5 4 11 Rodrigo Pineiro FW 5-9 146 05/05/1999 Montevideo, Uruguay 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 12 Alistair Johnston DF 5-11 170 10/08/1998 Vancouver, BC, Canada 3 3 0 0 21 18 0 1 13 Irakoze Donasiyano MF 5-9 155 02/03/1998 Tanzania 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 14 Daniel Rios FW 6-1 185 02/22/1995 Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico 0 0 0 0 18 8 4 0 15 Eric Miller DF 6-1 175 01/15/1993 Woodbury, MN 0 0 0 0 121 104 0 3 17 CJ Sapong FW 5-11 185 12/27/1988 Manassas, VA 3 0 0 0 279 210 71 25 18 Dylan Nealis DF 5-11 175 07/30/1998 Massapequa, NY 1 0 0 0 20 10 0 0 19 Alex Muyl MF 5-11 175 09/30/1995 New York, NY 3 2 0 0 134 86 11 20 20 Anibal -

Download This Press Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 8, 2019 CONTACT: Mayor’s Press Office 312.744.3334 [email protected] MAYOR LIGHTFOOT, THE CHICAGO PARK DISTRICT AND CHICAGO FIRE SOCCER CLUB ANNOUNCE THE TEAM’S RETURN TO SOLDIER FIELD The Fire to Return to Soldier Field starting in March 2020 CHICAGO – Mayor Lori E. Lightfoot, Chicago Park District Superintendent & CEO Mike Kelly, and the Chicago Fire Soccer Club today announced that the team will return to Soldier Field to play their home games starting in 2020. SeatGeek Stadium in Bridgeview, Illinois has been home to the Fire since 2006, and the team will continue to utilize the stadium as a training facility and headquarters for Chicago Fire Youth development programs. “Chicago is the greatest sports town in the world, and I am thrilled to welcome the Chicago Fire back home to Solider Field, giving families in every one of our neighborhoods a chance to cheer for their team in the heart of our beautiful downtown,” said Mayor Lori E. Lightfoot. “From arts, culture, business, sports, and entertainment, Chicago is second to none in creating a dynamic destination for residents and visitors alike, and I look forward to many years of exciting Chicago Fire soccer to come.” The Chicago Fire was founded in 1997 and began playing in Major League Soccer in 1998. The Fire won the MLS Cup and the Lamar Hunt U.S. Open Cup its first season, and additional U.S. Open Cups in 2000, 2003, and 2006. As an early MLS expansion team, the Fire played at Soldier Field from 1998 until 2001 and then from 2003 to 2005 before moving to Bridgeview in 2006. -

Senate Floor

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 163 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, OCTOBER 31, 2017 No. 176 Senate The Senate met at 10 a.m. and was As I said last week, no single bill or As government officials review this called to order by the President pro program is going to solve this crisis on morning’s report and as agencies de- tempore (Mr. HATCH). its own. Only a sustained, committed velop new plans to fulfill its objectives, f effort can do that. That has been my I will continue to work with partners view over the many years that I have in Washington and Kentucky to ad- PRAYER been involved in this issue, from the dress this important crisis. The goal, of The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- first time I invited the White House course, is that one day we can finally fered the following prayer: drug czar down to Eastern Kentucky to put the pain of opioid abuse behind us Let us pray. see the challenges posed by prescrip- once and for all. Sovereign Lord of the Universe, we tion drug abuse firsthand to my work f pray today for all who govern. Use our on other initiatives, such as helping JUDICIAL NOMINATIONS Senators for Your glory, providing pass a law to help address the tragedy them with wisdom to live with the in- of babies born addicted to drugs. Mr. MCCONNELL. Mr. President, yes- tegrity that brings stability to nations. -

In This Issue Portland Home Market for June 2014

Portland Metro Area Home Market Report For June 2014 http://www.movingtoportland.net Voice 503.497.2984 [email protected] In This Issue Portland Home Market: June 2014 Cost of Residential Homes by Community: June 2014 Mortgages Weather Summary for Portland Metro Area Portland Property Taxes: Who Gets the Money Portland Mavericks: The Battered Bastards of Baseball Portland Home Market for June 2014 June 2014 Highlights: Strongest June Closings since 2007 Closed sales enjoyed a solid month this June in the Portland metro area. The 2,617 closings showed a 4.2% increase over the 2,511 closings from last June. In fact, this was the strongest June for closed sales in the region since 2007 when there were 2,731! Pending sales, at 2,965, rose 5.7% compared to last June’s 2,804, but fell slightly (-0.8%) compared to the 2,989 offers accepted just last month. New listings (4,078) were 8.7% stronger than June 2013 (3,751) but fell 2.7% from May’s 4,192. There are currently 7,250 active residential listings in the Portland metro area. Total market time fell again in June to 59 days. Inventory remained stable for the third consecutive month, and sits at 2.8 months. Page 2 Portland Metro Area Home Prices for June 2014 Average and Median Sales Price: Median Price Up 8.7% During First Half of Year The average price the first half of the year was $328,900, up 8.7% from the same time frame in 2013 when the average was $302,700. -

Major League Soccer/Triple-A Baseball Task Force Report and Recommendations Background: Summary of Initial Proposal

Major League Soccer/Triple-A Baseball Task Force Report and Recommendations March 2009 Background: For the past couple years, Major League Soccer (MLS) has been in an expansion mode. MLS returned to San Jose in 2008. Seattle was awarded the 15th team franchise in early 2008 and will begin play this year. Also in 2008, MLS awarded the 16 th franchise to Chester, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Philadelphia. The Chester team will start play in 2010. In the spring of 2008, MLS announced that it intended to take proposals for two additional expansion franchises which would begin play in 2011. Merritt Paulson, the owner of the Portland Timbers and Portland Beavers, approached the City and indicated he wanted to submit a proposal to MLS for one of the available expansion franchises. The franchise fee paid to MLS for an expansion team has increased dramatically during the recent expansion period. The Toronto team began play in 2007 and paid a fee of $10 million. The next year, the San Jose team began play and paid a fee of $20 million. In 2008, Seattle and Chester paid $30 million for their expansion teams. The announced fee for the two franchises to be awarded in 2009 is $40 million. Shortstop LLC is the name of the business entity formed by Mr. Paulson for the operation of the teams. The current Portland Timbers are a First Division team in the United Soccer League. This league shares an affiliation with Major League Soccer (MLS) and with the international soccer governing body FIFA. MLS is the highest level of competitive soccer played in the United States. -

Baseball Fiction 2014

1. Abrahams, Peter; THE FAN; Warner, 1995; fn/fn. Novel about a crazed fan obsessed with a star outfielder was the basis for the movie starring Robert DeNiro & Wesley Snipes. - 6.00 2. Andersen, Richard; MUCKALUCK; Delacorte, 1980; g+/vg (dj spine faded). A novel about cowboys, Indians and baseball. - 10.00 3. Asinof, Eliot & Bouton, Jim; STRIKE ZONE; Viking, 1994; fn/fn. Two of baseball's more notable literary figures collaborate on this mystery about gambling and the game. Bouton takes the role of a career minor-leaguer called up to pitch a big game. Asinof is the veteran plate umpire. SIGNED by Asinof AND Bouton. - 45.00 4. Asinof, Eliot; MAN ON SPIKES; McGraw Hill, 1955; vg (spine is darkened, but still legible)/vg. Asinof's 1st novel tells the story of a career minor leaguer. Reviewing the 1998 reissue for the "San Francisco Chronicle", Harlan Ellison wrote that Asinof "makes it agonizingly clear to anyone who thinks Mr. Lincoln freed all the slaves that, from the earliest days of major league baseball till 1965, a rookie signed to a farm team might as well have spread-eagled himself on the mound, crossed his legs and waited for them to drive in the spikes. For a pittance they bought 'em, and forever they owned 'em." SIGNED by Eliot Asinof. - 125.00 Other cop: Popular Library, 1955 PB reprint (same yr. of pub as hardcover); g+ (other than age "toning", as new). - 10.00 5. Asinof, Eliot; OFF-SEASON; Southern Illinois Univ. Press, 2000; fn/fn. High school hero turned superstar pro pitcher returns to dedicate a ball field he's paid for & donated to his home town only to confront his demons, his past & murder (among other things). -

The Case Study of the Ron Tonkin Field/ Hillsboro Hops Public-Private Partnership

CASE STUDY The Case Study of the Ron Tonkin Field/ Hillsboro Hops Public-Private Partnership The Hillsboro City Council set out to expand the Gordon Faber Recreation Complex and bring professional baseball to town as a means of enhancing residents’ quality of life. In doing so, the Council had several goals, including: 1. To create a facility that could be used year-round for youth sports, adult sports, special and community events. 2. To continue to support fields for public use, particularly to support athletic programs of the Hillsboro School District, as well as regional and state university athletic programs. 3. To support local youth with the creation of new jobs. 4. To support economic development in Hillsboro and help local businesses by increasing tourism spending and related entertainment spending. 5. To build regional and national awareness of Hillsboro as a means of highlighting our exceptional community. After a significant investment of time to gather and evaluate all available information in order to reach the best informed decision, the Hillsboro City Council authorized a public-private partnership with Short Season, LLC, owners of the soon-to-be named Hillsboro Hops. The agreement called for Short Season, LLC to relocate the team from Yakima and begin play in Hillsboro in June 2013 at the Gordon Faber Recreation Complex. In the Hops’ first three years playing at Hillsboro Ballpark/Ron Tonkin Field (renamed in 2014), the team sold more than 430,000 tickets. In addition to hosting the only professional baseball team in the Portland metro area, Ron Tonkin Field continues to play host to high school football, soccer, baseball, and charity fundraising events. -

History of Fairfax City

HISTORY OF FAIRFAX CITY The City of Fairfax began as the Town of Providence in 1805, a community built around the Fairfax County Courthouse. Completed in 1800 at the corner of Little River Turnpike and Ox Road, the area was a crossroads of conflict during the American Civil War with hardships and disrupted lives for everyone. From a crossroads of conflict, the area became a crossroads of commerce in the late nineteenth century when the dairy industry propelled economic rebirth and the building of schools, churches, homes, barns, and businesses and in 1874 the Town of Providence officially became the Town of Fairfax. The early 20th century ushered in a myriad of technological and transportation changes and the emergence of civic organizations, sports clubs, a Town police unit, and a volunteer fire company. World War II spurred rapid growth across the region in housing, business ventures, and population and Fairfax quickly changed from a rural to a suburban community. The Town of Fairfax deeded a 150-acre tract of land in 1959 to the University of Virginia to establish a permanent home for what is now George Mason University. In 1961, the Town of Fairfax was incorporated as the independent City of Fairfax and in 1962 a new City Hall was completed. Rich in history and heritage, residents and visitors enjoy a small-town atmosphere and an abundance of cultural and recreational pursuits in the midst of a bustling metropolitan area. As the City's first mayor, John C. Wood said in 1962 - "Fairfax has a wonderful past and present and an even greater future." HOW DID THE JULY 4TH CELEBRATION BEGIN IN FAIRFAX CITY? Fairfax City’s Independence Day Parade and Fireworks began in 1967 and was organized by the Delta Alpha Chapter of Beta Sigma Phi Sorority. -

Honors Portland Timbers for Their 2015 MLS Cup Victory

78th Oregon Legislative Assembly - 2016 Regular Session MEASURE: SCR 207 STAFF MEASURE SUMMARY CARRIER: Rep. Williamson House Committee On Rules Fiscal: No fiscal impact Revenue: No Revenue Impact Action Date: 02/29/16 Action: Be Adopted. Meeting Dates: 02/29 Vote: Yeas: 8 - Barnhart, Gilliam, Hoyle, Huffman, Kennemer, Rayfield, Williamson, Wilson Exc: 1 - Smith Warner Prepared By: Erin Seiler, Committee Administrator WHAT THE MEASURE DOES: Honors Portland Timbers for their 2015 MLS Cup victory. ISSUES DISCUSSED: Success of Timbers EFFECT OF COMMITTEE AMENDMENT: No amendment. BACKGROUND: The Portland Timbers earned their first Major League Soccer (MLS) championship on December 6, 2015, capturing the 2015 MLS Cup trophy with a 2 to 1 victory over Columbus Crew SC. Led by head coach Caleb Porter, the Portland Timbers finished a winning season that landed them third in the Western Conference, a placement that earned them the right to advance to the MLS Cup Playoffs. The team progressed without a loss in their post-season playoff march to win the cup final, defeating Sporting Kansas City, Vancouver Whitecaps FC, FC Dallas and Columbus Crew SC. Throughout the season, the Portland Timbers were spurred to victory by the rousing cheers of the Timbers Army and the team’s legion of supporters who have filled Providence Park to capacity for every regular-season and playoff match since the Portland Timbers’ inaugural MLS season. Senate Concurrent Resolution 207 honors the Portland Timbers for their victory in winning the 2015 MLS Cup. This summary has not been adopted or officially endorsed by action of the Committee. 1 of 1 . -

PHILADELPHIA UNION V PORTLAND TIMBERS (Sept

PHILADELPHIA UNION v PORTLAND TIMBERS (Sept. 10, PPL Park, 7:30 p.m. ET) 2011 SEASON RECORDS PROBABLE LINEUPS ROSTERS GP W-L-T PTS GF GA PHILADELPHIA UNION Union 26 8-7-11 35 35 30 1 Faryd Mondragon (GK) at home 13 5-1-7 22 19 15 3 Juan Diego Gonzalez (DF) 18 4 Danny Califf (DF) 5 Carlos Valdes (DF) Timbers 26 9-12-5 32 33 41 MacMath 6 Stefani Miglioranzi (MF) on road 12 1-8-3 6 7 22 7 Brian Carroll (MF) 4 5 8 Roger Torres (MF) LEAGUE HEAD-TO-HEAD 25 Califf Valdes 15 9 Sebastien Le Toux (FW) ALL-TIME: 10 Danny Mwanga (FW) Williams G Farfan Timbers 1 win, 1 goal … 7 11 Freddy Adu (MF) Union 0 wins, 0 goals … Ties 0 12 Levi Houapeu (FW) Carroll 13 Kyle Nakazawa (MF) 14 Amobi Okugo (MF) 2011 (MLS): 22 9 15 Gabriel Farfan (MF) 5/6: POR 1, PHI 0 (Danso 71) 11 16 Veljko Paunovic (FW) Mapp Adu Le Toux 17 Keon Daniel (MF) 18 Zac MacMath (GK) 19 Jack McInerney (FW) 16 10 21 Michael Farfan (MF) 22 Justin Mapp (MF) Paunovic Mwanga 23 Ryan Richter (MF) 24 Thorne Holder (GK) 25 Sheanon Williams (DF) UPCOMING MATCHES 15 33 27 Zach Pfeffer (MF) UNION TIMBERS Perlaza Cooper Sat. Sept. 17 Columbus Fri. Sept. 16 New England PORTLAND TIMBERS Fri. Sept. 23 at Sporting KC Wed. Sept. 21 San Jose 1 Troy Perkins (GK) 2 Kevin Goldthwaite (DF) Thu. Sept. 29 D.C. United Sat. Sept. 24 at New York 11 7 4 Mike Chabala (DF) Sun.