Michel Foucault, Philosopher? a Note on Genealogy and Archaeology1 Rudi Visker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Foucault's Darwinian Genealogy

genealogy Article Foucault’s Darwinian Genealogy Marco Solinas Political Philosophy, University of Florence and Deutsches Institut Florenz, Via dei Pecori 1, 50123 Florence, Italy; [email protected] Academic Editor: Philip Kretsedemas Received: 10 March 2017; Accepted: 16 May 2017; Published: 23 May 2017 Abstract: This paper outlines Darwin’s theory of descent with modification in order to show that it is genealogical in a narrow sense, and that from this point of view, it can be understood as one of the basic models and sources—also indirectly via Nietzsche—of Foucault’s conception of genealogy. Therefore, this essay aims to overcome the impression of a strong opposition to Darwin that arises from Foucault’s critique of the “evolutionistic” research of “origin”—understood as Ursprung and not as Entstehung. By highlighting Darwin’s interpretation of the principles of extinction, divergence of character, and of the many complex contingencies and slight modifications in the becoming of species, this essay shows how his genealogical framework demonstrates an affinity, even if only partially, with Foucault’s genealogy. Keywords: Darwin; Foucault; genealogy; natural genealogies; teleology; evolution; extinction; origin; Entstehung; rudimentary organs “Our classifications will come to be, as far as they can be so made, genealogies; and will then truly give what may be called the plan of creation. The rules for classifying will no doubt become simpler when we have a definite object in view. We possess no pedigrees or armorial bearings; and we have to discover and trace the many diverging lines of descent in our natural genealogies, by characters of any kind which have long been inherited. -

A Foucauldian Analysis of Black Swan

Introduction In the 2010 movie Black Swan , Nina Sayers is filmed repeatedly practicing a specific ballet turn after her teacher mentioned her need for improvement earlier that day. Played by Natalie Portman, Nina is shown spinning in her room at home, sweating with desperation and determination trying to execute the turn perfectly. Despite the hours of gruesome rehearsal, Nina must nail every single aspect of this particular turn to fully embody the role she is cast in. After several attempts at the move, she falls, exhausted, clutching her newly twisted ankle in agony. Perfection, as shown in this case, runs hand in hand with pain. Crying to herself, Nina holds her freshly hurt ankle and contemplates how far she will go to mold her flesh into the perfectly obedient body. This is just one example in the movie Black Swan in which the main character Nina, chases perfection. Based on the demanding world of ballet, Darren Aronofsky creates a new-age portrayal of the life of a young ballet dancer, faced with the harsh obstacles of stardom. Labeled as a “psychological thriller” and horror film, Black Swan tries to capture Nina’s journey in becoming the lead of the ever-popular “Swan Lake.” However, being that the movie is set in modern times, the show is not about your usual ballet. Expecting the predictable “Black Swan” plot, the ballet attendees are thrown off by the twists and turns created by this mental version of the show they thought they knew. Similarly, the attendees for the movie Black Swan were surprised at the risks Aronofsky took to create this haunting masterpiece. -

Two Uses of Genealogy: Michel Foucault and Bernard Williams 90 1

the practices which we might use genealogy to inquire into. Of course, 1 these two thinkers each used genealogy in very different senses insofar as I Chapter 5 Nietzsche's genealogy was an attempt to undermine and subvert certain! modern moral practices whereas Williams' was an attempt to vindicate i Two uses of genealogy: Michel Foucault and and strengthen certain modern moral notions concerning the value ofl Bernard Williams practices of truthfulness. Although the minimal conclusion that Foucault's genealogy differs I Colin Koopman from Nietzsche's and Williams' genealogy may not be all that surprising" what is nonetheless revealing is an exploration of the specific terms oni which these varying conceptions of genealogy can be differentiated. Such! an exploration particularly helps us recognize the complex relationship I The notion CMn1lWn to all the work that I have done . .. is that of problematization. between genealogy and critique. It is my claim that Foucault's project dif-i -Michel Foucault, 1984, 'The Concern/or Truth' fers from more normatively ambitious uses of genealogy and that muchI i light is shed on the way in which Foucault used genealogy as a critical appa ratus by explicating this difference. Foucault used genealogy to develop a i Michel Foucault's final description of his genealogical and archaeological form of critique that did not rely on the traditional normative ambitions inquiries in terms of the concept of 'problematization' is, most commen which have motivated so much of modern philosophy. Foucault, perhaps -

Philosophical Genealogy: a User's Guide

Philosophical Genealogy: A User's Guide MPhil Stud Victor Braga Weber University College London 2019 1 I, Victor Braga Weber, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Victor Braga Weber, August 28, 2019 2 Abstract In what way might our past effect our current philosophical outlook? More particularly, is there any philosophical value in investigating the contexts from which our philosophical outlooks originate? Analytic philosophy has historically responded antagonistically to the suggestion that looking to our past for answers is valuable. Yet some philosophers argue that the search for the origins of our philosophical outlook can be a source of great (meta-)philosophical insight. One such strand are the so-called genealogists. The purpose of this thesis is to understand what the promise of philosophical genealogy is, and whether it can be fulfilled. A challenge for my project is that the term ‘genealogy’ has been used to describe very different kinds of things (Section I). As such, I propose to develop a taxonomy of conceptions of genealogy (Section II), identify what the distinctive features of its members are (Section III), and what kind of insight they can give us (Section IV). In the final section (Section V), I return to the question of whether there is any non-trivial claim we can make about what features are shared by the disparate conceptions I identify. I argue that there is, but not at the level of a common philosophical method. -

Can Human Rights Have Merit in Foucault's Disciplinary Society?

Can Human Rights Have Merit in Foucault’s Disciplinary Society? Alexandra Solheim Thesis presented for the degree of MASTER IN PHILOSOPHY Supervised by Professor Arne Johan Vetlesen and Professor Espen Schaaning Department of Philosophy, Classics, History of Art and Ideas UNIVERSITY OF OSLO December 2018 Can Human Rights have Merit in Foucault’s Disciplinary Society? II © Alexandra Solheim 2018 Can Human Rights Have Merit in Foucault’s Disciplinary Society? Alexandra Solheim http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo III Summary This thesis’s inquiry sets out to study the apparent irreconcilability between Foucault’s notion of disciplinary power and the idea of human rights. By reconceptualising human rights, this thesis attempts to redeem the merit of human rights in the context of Foucault’s disciplinary society. This thesis shall, firstly, address four issues of human rights, which are: the large number of contestations concerning its content, the increasingly expanding scope, the technocratic characteristics of human rights practice, and lastly, the adverse effects of human right struggles. By looking at Foucault’s power as disciplinary, it can account for and explain the challenges identified. Foucault does not envision himself to provide a normative theory, but rather a descriptive theory. This might illuminate why and how rights become problematic in practice. If we adopt Foucault’s notion of power, it appears that it would discredit the idea of human rights altogether. In this view, human rights reinforce power structures instead of opposing them. Firstly, disciplinary power renders emancipatory human rights nonsensical, as power is not uniform and the opposite of freedom. -

Carceral Biocitizenship

2 Carceral Biocitizenship The Rhetorics of Sovereignty in Incarceration Sarah Burgess and Stuart J. Murray Introduction On October 19, 2007, nineteen- year- old Ashley Smith died of self- inflicted strangulation while on suicide watch at the Grand Valley Institution for Women in Kitchener, Ontario, Canada. As she tied a liga- ture around her neck, correctional officers, who had been instructed not to enter into her cell if she was still breathing, watched— and in com- pliance with Canadian regulations,1 videorecorded—her death. As the video footage attests, they entered her cell only when she was nonrespon- sive and could not be resuscitated. Six days later, the three correctional officers who stood by and watched Smith’s suicide were charged, along with one of their supervisors, with criminal negligence causing death, while the warden and deputy warden were fired. Criminal charges were later dropped. The case gained some attention following the June 2008 publication of a report by the Office of the Correctional Investigator of Canada titled A Preventable Death; and public outcry grew considerably when Canada’s national CBC News Network’s The Fifth Estate broadcast two special investigative reports in January and November 2010, titled “Out of Control” and “Behind the Wall,” respectively. The latter broad- cast included the video footage of Smith’s death, and the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) came under intense scrutiny for its treatment of prisoners with mental health problems. What emerged over the course of the Coroner’s Inquests (there were two, in 2011 and 2012) were the systemic yet oftentimes highly coordi- nated, seemingly intentional failures and abuses on the part of the CSC. -

Beyond Resistance: a Response to Žižek's Critique of Foucault's Subject

ParrHesia number 5 • 2008 • 19-31 BEYOND RESISTANCE: A RESPONSE TO ŽiŽek’s critique of foucault’s subject of freedom Aurelia Armstrong introduction in a brief introduction to his lively discussion of judith butler’s work in The Ticklish Subject, slavoj Žižek outlines the paradoxes which he believes haunt michel foucault’s treatment of the relationship between resistance and power. taking into account the trajectory of foucault’s thought from his early studies of madness to his final books on ethics, Žižek suggests that foucault employs two models of resistance which are not finally reconcilable. on the first model, resistance is understood to be guaranteed by a pre-existing foundation which escapes or eludes the powers that bear down on it from outside. We can see this conception of resistance at work in foucault’s exhortation in Madness and Civilization to liberate madness from medico-legal discourse and “let madness speak itself,” and in his call in The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1 to “break away from the agency of sex” and “counter the grips of power with the claims of bodies, pleasures, and knowledges, in their multiplicity and their possibility of resistance.”1 Yet even in this latter work—and in Discipline and Punish—we find a second model of resistance. on this other model resistance is understood to be generated by the very power that it opposes. in other words normalizing-disciplinary power is productive, rather than repressive, of that upon which it acts. as Foucault explains in Discipline and Punish, “the man described for us, whom we are invited to free, is already in himself the effect of a subjection much more profound than himself.”2 one way to distinguish between these two models of resistance is to point to the different conceptions of power underpinning each. -

Fugitive Life: Race, Gender, and the Rise of the Neoliberal-Carceral State

Fugitive Life: Race, Gender, and the Rise of the Neoliberal-Carceral State A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Stephen Dillon IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Regina Kunzel, Co-adviser Roderick Ferguson, Co-adviser May 2013 © Stephen Dillon, 2013 Acknowledgements Like so many of life’s joys, struggles, and accomplishments, this project would not have been possible without a vast community of friends, colleagues, mentors, and family. Before beginning the dissertation, I heard tales of its brutality, its crushing weight, and its endlessness. I heard stories of dropouts, madness, uncontrollable rage, and deep sadness. I heard rumors of people who lost time, love, and their curiosity. I was prepared to work 80 hours a week and to forget how to sleep. I was prepared to lose myself as so many said would happen. The support, love, and encouragement of those around me means I look back on writing this project with excitement, nostalgia, and appreciation. I am deeply humbled by the time, energy, and creativity that so many people loaned me. I hope one ounce of that collective passion shows on these pages. Without those listed here, and so many others, the stories I heard might have become more than gossip in the hallway or rumors over drinks. I will be forever indebted to Rod Ferguson’s simple yet life-altering advice: “write for one hour a day.” Adhering to this rule meant that writing became a part of me like never before. -

Herculine Barbin and the Omission of Biopolitics from Judith Butler's

Regular article Feminist Theory 2014, Vol. 15(1) 73–88 Herculine Barbin and the ! The Author(s) 2014 Reprints and permissions: omission of biopolitics from sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1464700113512737 Judith Butler’s gender fty.sagepub.com genealogy Jemima Repo University of Helsinki, Finland Abstract This article argues that Judith Butler’s neglect of biopolitics in her reading of Michel Foucault’s work on sexuality leads her to propose a genealogy of gender ontology rather than conduct a genealogy of gender itself. Sex was not an effect of a cultural system for Foucault, but an apparatus of biopower that emerged in the eighteenth century for the administration of life. Butler, however, is interested in uncovering how something we call or identify as gender manifests itself in different times and contexts, rather than asking what relations of power made necessary the emergence of gender as a discourse. After examining the theoretical configurations underpinning Butler’s engagement with Foucault’s Herculine Barbin, I suggest a more biopolitically informed reading of how the material body becomes captured by the discourses of sexuality and sex. Finally, the article sets out preliminary questions with which a more strictly Foucauldian genealogy of gender might be conducted. Keywords Desire, gender theory, genealogy, hermaphroditism, Judith Butler, Michel Foucault, sex, sexuality While Michel Foucault’s genealogy of sexuality has prominently influenced gender theory since the late 1980s, biopolitics has been given less theoretical importance in the formulation of theories of gender. Most notably, Judith Butler’s gender theory projects Foucault’s historically contingent understanding of the sexuality discourse onto the category of ‘gender’ as a historically constructed manifestation of identity. -

Globalization and the Roman Empire: the Genealogy of ‘Empire’

SEMATA, Ciencias Sociais e Humanidades, ISSN 1137-9669, 2011, vol. 23: 99-113 Globalization and the Roman empire: the genealogy of ‘Empire’ RICHARD HINGLEY University of Durham, Reino Unido Resumen La presencia de conceptos e ideas contemporáneas en los estudios sobre la Roma antigua es inevitable. No son excepción los análisis que, desde 1990, ponen en tela de juicio el mismo concepto de romanización. Por ese motivo, el término “globalización” aplicado a la Roma antigua puede ser útil porque hace el anacronismo más evidente y nos obliga a tenerlo en cuenta. Palabras clave: Imperialismo, genealogía, Hardt-Negri, romanización. Abstract The use of concepts and ideas taken from the contemporary World in the studies on ancient Rome simply cannot be avoided. The studies that since 1990s onwards have criticized the term “Roman- ization” are not an exception. For this reason, the concept of “globalization” in reference to Ancient Rome can be helpful since it makes the anachronism in contemporary accounts all more evident. Keywords: Imperialism, genealogy, Hardt-Negri, Romanization. “The Roman Empire is worth studying … not as a means of unders- tanding better how to run an empire and dominate other countries, or finding a justification for humanitarian or military intervention, but as a means of understanding and questioning modern conceptions of empire and imperialism, and the way they are deployed in contemporary po- litical debates” (N. Morley, The Roman Empire: Roots of Imperialism, New York, 2010, Pluto Books, p.10). Recibido: 14-03-2011. Aceptado: 4-05-2011 100 RICHARD HINGLEY: Globalization and the Roman empire: the genealogy of ‘Empire’ 1. -

Foucault Lectures the Beginning of a Study of Biopower

Foucault Lectures A series published by Foucault Studies © Verena Erlenbusch-Anderson ISSN: 2597-2545 DOI: https://doi.org/10.22439/fsl.vi0.6151 Foucault Lectures, Vol III, no. 1, 5-26, December 2020 ARTICLE The Beginning of a Study of Biopower: Foucault’s 1978 Lectures at the Collège de France VERENA ERLENBUSCH-ANDERSON Syracuse University, USA ABSTRACT. While Foucault introduced the 1978 lecture course Security, Territory, Population as a study of biopower, the reception of the lectures has largely focused on other concepts, such as governmentality, security, liberalism, and counter-conduct. This paper situates the lecture course within the larger context of Foucault’s development of an analytics of power to explore in what sense Security, Territory, Population can be said to constitute a study of biopower. I argue that the 1978 course is best understood as a continuation-through-transformation of Foucault’s earlier work. It revisits familiar material to supplement Foucault’s microphysics of power, which he traced in institutions like prisons or asylums and with regard to its effects on the bodies of individuals, with a genealogy of practices of power that target the biological life of the population and give rise to the modern state. Keywords: Foucault, biopower, governmentality, (neo)liberalism, genealogy INTRODUCTION On January 11, 1978, after a sabbatical year and an almost two-year long absence from his responsibilities to present ongoing research at the Collège de France, Michel Foucault returned to the lectern on January 11, -

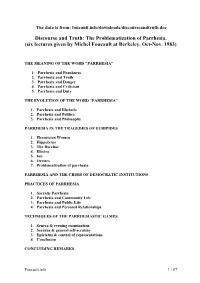

Discourse and Truth: the Problematization of Parrhesia. (Six Lectures Given by Michel Foucault at Berkeley, Oct-Nov

The data is from: foucault.info/downloads/discourseandtruth.doc Discourse and Truth: The Problematization of Parrhesia. (six lectures given by Michel Foucault at Berkeley, Oct-Nov. 1983) THE MEANING OF THE WORD "PARRHESIA" 1. Parrhesia and Frankness 2. Parrhesia and Truth 3. Parrhesia and Danger 4. Parrhesia and Criticism 5. Parrhesia and Duty THE EVOLUTION OF THE WORD “PARRHESIA” 1. Parrhesia and Rhetoric 2. Parrhesia and Politics 3. Parrhesia and Philosophy PARRHESIA IN THE TRAGEDIES OF EURIPIDES 1. Phoenician Women 2. Hippolytus 3. The Bacchae 4. Electra 5. Ion 6. Orestes 7. Problematization of parrhesia PARRHESIA AND THE CRISIS OF DEMOCRATIC INSTITUTIONS PRACTICES OF PARRHESIA 1. Socratic Parrhesia 2. Parrhesia and Community Life 3. Parrhesia and Public Life 4. Parrhesia and Personal Relationships TECHNIQUES OF THE PARRHESIASTIC GAMES 1. Seneca & evening examination 2. Serenus & general self-scrutiny 3. Epictetus & control of representations 4. Conclusion CONCLUDING REMARKS Foucault.info 1 / 67 The Meaning of the Word " Parrhesia " The word "parrhesia" [παρρησία] appears for the first time in Greek literature in Euripides [c.484-407 BC], and occurs throughout the ancient Greek world of letters from the end of the Fifth Century BC. But it can also still be found in the patristic texts written at the end of the Fourth and during the Fifth Century AD -dozens of times, for instance, in Jean Chrisostome [AD 345-407] . There are three forms of the word : the nominal form " parrhesia " ; the verb form "parrhesiazomai" [παρρησιάζοµαι]; and there is also the word "parrhesiastes"[παρρησιαστής] --which is not very frequent and cannot be found in the Classical texts.