Philosophical Genealogy: a User's Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Foucault's Darwinian Genealogy

genealogy Article Foucault’s Darwinian Genealogy Marco Solinas Political Philosophy, University of Florence and Deutsches Institut Florenz, Via dei Pecori 1, 50123 Florence, Italy; [email protected] Academic Editor: Philip Kretsedemas Received: 10 March 2017; Accepted: 16 May 2017; Published: 23 May 2017 Abstract: This paper outlines Darwin’s theory of descent with modification in order to show that it is genealogical in a narrow sense, and that from this point of view, it can be understood as one of the basic models and sources—also indirectly via Nietzsche—of Foucault’s conception of genealogy. Therefore, this essay aims to overcome the impression of a strong opposition to Darwin that arises from Foucault’s critique of the “evolutionistic” research of “origin”—understood as Ursprung and not as Entstehung. By highlighting Darwin’s interpretation of the principles of extinction, divergence of character, and of the many complex contingencies and slight modifications in the becoming of species, this essay shows how his genealogical framework demonstrates an affinity, even if only partially, with Foucault’s genealogy. Keywords: Darwin; Foucault; genealogy; natural genealogies; teleology; evolution; extinction; origin; Entstehung; rudimentary organs “Our classifications will come to be, as far as they can be so made, genealogies; and will then truly give what may be called the plan of creation. The rules for classifying will no doubt become simpler when we have a definite object in view. We possess no pedigrees or armorial bearings; and we have to discover and trace the many diverging lines of descent in our natural genealogies, by characters of any kind which have long been inherited. -

Two Uses of Genealogy: Michel Foucault and Bernard Williams 90 1

the practices which we might use genealogy to inquire into. Of course, 1 these two thinkers each used genealogy in very different senses insofar as I Chapter 5 Nietzsche's genealogy was an attempt to undermine and subvert certain! modern moral practices whereas Williams' was an attempt to vindicate i Two uses of genealogy: Michel Foucault and and strengthen certain modern moral notions concerning the value ofl Bernard Williams practices of truthfulness. Although the minimal conclusion that Foucault's genealogy differs I Colin Koopman from Nietzsche's and Williams' genealogy may not be all that surprising" what is nonetheless revealing is an exploration of the specific terms oni which these varying conceptions of genealogy can be differentiated. Such! an exploration particularly helps us recognize the complex relationship I The notion CMn1lWn to all the work that I have done . .. is that of problematization. between genealogy and critique. It is my claim that Foucault's project dif-i -Michel Foucault, 1984, 'The Concern/or Truth' fers from more normatively ambitious uses of genealogy and that muchI i light is shed on the way in which Foucault used genealogy as a critical appa ratus by explicating this difference. Foucault used genealogy to develop a i Michel Foucault's final description of his genealogical and archaeological form of critique that did not rely on the traditional normative ambitions inquiries in terms of the concept of 'problematization' is, most commen which have motivated so much of modern philosophy. Foucault, perhaps -

Michel Foucault, Philosopher? a Note on Genealogy and Archaeology1 Rudi Visker

PARRHESIA NUMBER 5 • 2008 • 9-18 MICHEL FOUCAULT, PHILOSOPHER? A NOTE ON GENEALOGY AND ARCHAEOLOGY1 Rudi Visker My title formulates a question that is mainly addressed to myself. Less elliptically formulated, it would read as follows: please explain why you, a professor in philosophy, have published over the years so many pages in which you kept referring to the work of someone who has authored a series of historical works on topics which, at first sight, have hardly any bearing on the discipline which your institution pays you to do research in. Whence this attraction to studies on madness, crime or sexuality? Wasn’t one book enough to make you realize that however enticing a reading such works may be, they bring little, if anything, for philosophy as such? I imagine my inquisitor wouldn’t rest if I were to point out to him that he seems badly informed and apparently unaware of the fact that Foucault by now has come to be accepted as an obvious part of the philosophical canon for the past century. Should I manage to convince him to take up a few of the books presenting his thought to philosophers, he would no doubt retort that what he had been reading mainly consisted of summaries of the aforementioned histories, and for the rest of exactly the kind of arguments that gave rise to his suspicion: accusations of nihilism, relativism, self-contradiction, critique without standards… And worse, if I were honest, I would have to agree that for all the fascination that it exerted on us philosophers, Foucault’s work also put us before a deep, and by now familiar embarrassment. -

Herculine Barbin and the Omission of Biopolitics from Judith Butler's

Regular article Feminist Theory 2014, Vol. 15(1) 73–88 Herculine Barbin and the ! The Author(s) 2014 Reprints and permissions: omission of biopolitics from sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1464700113512737 Judith Butler’s gender fty.sagepub.com genealogy Jemima Repo University of Helsinki, Finland Abstract This article argues that Judith Butler’s neglect of biopolitics in her reading of Michel Foucault’s work on sexuality leads her to propose a genealogy of gender ontology rather than conduct a genealogy of gender itself. Sex was not an effect of a cultural system for Foucault, but an apparatus of biopower that emerged in the eighteenth century for the administration of life. Butler, however, is interested in uncovering how something we call or identify as gender manifests itself in different times and contexts, rather than asking what relations of power made necessary the emergence of gender as a discourse. After examining the theoretical configurations underpinning Butler’s engagement with Foucault’s Herculine Barbin, I suggest a more biopolitically informed reading of how the material body becomes captured by the discourses of sexuality and sex. Finally, the article sets out preliminary questions with which a more strictly Foucauldian genealogy of gender might be conducted. Keywords Desire, gender theory, genealogy, hermaphroditism, Judith Butler, Michel Foucault, sex, sexuality While Michel Foucault’s genealogy of sexuality has prominently influenced gender theory since the late 1980s, biopolitics has been given less theoretical importance in the formulation of theories of gender. Most notably, Judith Butler’s gender theory projects Foucault’s historically contingent understanding of the sexuality discourse onto the category of ‘gender’ as a historically constructed manifestation of identity. -

Globalization and the Roman Empire: the Genealogy of ‘Empire’

SEMATA, Ciencias Sociais e Humanidades, ISSN 1137-9669, 2011, vol. 23: 99-113 Globalization and the Roman empire: the genealogy of ‘Empire’ RICHARD HINGLEY University of Durham, Reino Unido Resumen La presencia de conceptos e ideas contemporáneas en los estudios sobre la Roma antigua es inevitable. No son excepción los análisis que, desde 1990, ponen en tela de juicio el mismo concepto de romanización. Por ese motivo, el término “globalización” aplicado a la Roma antigua puede ser útil porque hace el anacronismo más evidente y nos obliga a tenerlo en cuenta. Palabras clave: Imperialismo, genealogía, Hardt-Negri, romanización. Abstract The use of concepts and ideas taken from the contemporary World in the studies on ancient Rome simply cannot be avoided. The studies that since 1990s onwards have criticized the term “Roman- ization” are not an exception. For this reason, the concept of “globalization” in reference to Ancient Rome can be helpful since it makes the anachronism in contemporary accounts all more evident. Keywords: Imperialism, genealogy, Hardt-Negri, Romanization. “The Roman Empire is worth studying … not as a means of unders- tanding better how to run an empire and dominate other countries, or finding a justification for humanitarian or military intervention, but as a means of understanding and questioning modern conceptions of empire and imperialism, and the way they are deployed in contemporary po- litical debates” (N. Morley, The Roman Empire: Roots of Imperialism, New York, 2010, Pluto Books, p.10). Recibido: 14-03-2011. Aceptado: 4-05-2011 100 RICHARD HINGLEY: Globalization and the Roman empire: the genealogy of ‘Empire’ 1. -

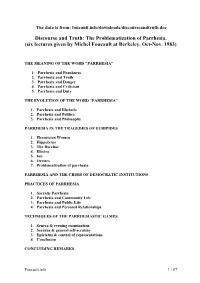

Discourse and Truth: the Problematization of Parrhesia. (Six Lectures Given by Michel Foucault at Berkeley, Oct-Nov

The data is from: foucault.info/downloads/discourseandtruth.doc Discourse and Truth: The Problematization of Parrhesia. (six lectures given by Michel Foucault at Berkeley, Oct-Nov. 1983) THE MEANING OF THE WORD "PARRHESIA" 1. Parrhesia and Frankness 2. Parrhesia and Truth 3. Parrhesia and Danger 4. Parrhesia and Criticism 5. Parrhesia and Duty THE EVOLUTION OF THE WORD “PARRHESIA” 1. Parrhesia and Rhetoric 2. Parrhesia and Politics 3. Parrhesia and Philosophy PARRHESIA IN THE TRAGEDIES OF EURIPIDES 1. Phoenician Women 2. Hippolytus 3. The Bacchae 4. Electra 5. Ion 6. Orestes 7. Problematization of parrhesia PARRHESIA AND THE CRISIS OF DEMOCRATIC INSTITUTIONS PRACTICES OF PARRHESIA 1. Socratic Parrhesia 2. Parrhesia and Community Life 3. Parrhesia and Public Life 4. Parrhesia and Personal Relationships TECHNIQUES OF THE PARRHESIASTIC GAMES 1. Seneca & evening examination 2. Serenus & general self-scrutiny 3. Epictetus & control of representations 4. Conclusion CONCLUDING REMARKS Foucault.info 1 / 67 The Meaning of the Word " Parrhesia " The word "parrhesia" [παρρησία] appears for the first time in Greek literature in Euripides [c.484-407 BC], and occurs throughout the ancient Greek world of letters from the end of the Fifth Century BC. But it can also still be found in the patristic texts written at the end of the Fourth and during the Fifth Century AD -dozens of times, for instance, in Jean Chrisostome [AD 345-407] . There are three forms of the word : the nominal form " parrhesia " ; the verb form "parrhesiazomai" [παρρησιάζοµαι]; and there is also the word "parrhesiastes"[παρρησιαστής] --which is not very frequent and cannot be found in the Classical texts. -

Archaeology And/Or Genealogy: Agamben's Transformation Of

Journal of Italian Philosophy, Volume 1 (2018) Archaeology and/or Genealogy: Agamben’s Transformation of Foucauldian Method Stephen Howard Attentive readers of Giorgio Agamben’s Homo Sacer project will no doubt have noticed Agamben’s vacillating descriptions of his philosophical method as ‘archaeology’ or ‘genealogy’. These terms derive most clearly from Michel Foucault, a fact that Agamben underlines by regularly situating the Homo Sacer project in relation to the French thinker, as development or completion of Foucault’s work on governmentality, power and biopolitics (1998, p.3–7; 2011, xi– xiii). However, despite employing Foucault’s terms, Agamben furnishes ‘archaeology’ and ‘genealogy’ with meanings which deviate significantly from Foucault’s use. We will here return to Foucault’s use of these terms to describe his method in distinct periods of his work, in order to illuminate the singular way that Agamben develops the archaeological and genealogical methodologies. I exemplify Agamben’s approach through one of the later, more political-theological contributions to the Homo Sacer series, with the aim of helping to clarify the place that these apparently esoteric works occupy in the series’ general political project. Finally, I show that Walter Benjamin is the key figure in the constellation informing Agamben’s archaeological-genealogical approach and examine the philosophical consequences of Agamben’s transformation of Foucault’s methods. 1. Agamben’s conflation of archaeology and genealogy Agamben’s 2008 book on method, The Signature of all Things, and its third chapter on ‘Philosophical Archaeology’, is the first place to look for an account of the significance of archaeology and genealogy for the Homo Sacer project. -

Spaces and Identities in Border Regions

Christian Wille, Rachel Reckinger, Sonja Kmec, Markus Hesse (eds.) Spaces and Identities in Border Regions Culture and Social Practice Christian Wille, Rachel Reckinger, Sonja Kmec, Markus Hesse (eds.) Spaces and Identities in Border Regions Politics – Media – Subjects An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-3-8394-2650-0. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No- Derivatives 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non-commer- cial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ To create an adaptation, translation, or derivative of the original work and for commer- cial use, further permission is required and can be obtained by contacting rights@ transcript-verlag.de Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures, photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may be required from the rights holder. The obligation to research and clear permission lies solely with the party re-using the material. © 2015 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche -

What Is Genealogy?

What is Genealogy? By Mark Bevir I. CONTACT INFORMATION Dept. of Political Science, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-1950, USA Email: [email protected] II. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Mark Bevir is Professor of Political Science at the University of California, Berkeley. His recent publications include New Labour: A Critique (Routledge, 2005); The Logic of the History of Ideas (Cambridge University Press, 1999); and, with R.A.W. Rhodes, both Governance Stories (Routledge, 2006), and Interpreting British Governance (Routledge, 2003). Abstract This paper offers a theory of genealogy, explaining its rise in the nineteenth century, its epistemic commitments, its nature as critique, and its place in the work of Nietzsche and Foucault. The crux of the theory is recognition of genealogy as an expression of a radical historicism, rejecting both appeals to transcendental truths and principles of unity or progress in history, and embracing nominalism, contingency, and contestability. In this view, genealogies are committed to the truth of radical historicism and, perhaps more provisionally, the truth of their own empirical content. Similarly, genealogies operate as denaturalizing critiques of ideas and practices that hide the contingency of human life behind formal ahistorical or developmental perspectives. Keywords Genealogy, Historicism, Critique, Nietzsche, Foucault What is Genealogy? This issue of the Journal of the Philosophy of History explores genealogy. A genealogy is a historical narrative that explains an aspect of human life by showing how it came into being. The narratives may be more or less grounded in facts or more or less speculative, but they are always historical. Of course the word genealogy may be used in quite other ways. -

A Genealogy of (Bio)Political Contestation During the Reform of the Mental Health Act 1983 in England and Wales

A genealogy of (bio)political contestation during the reform of the Mental Health Act 1983 in England and Wales Louisa Jane Cadman Submitted for the degree of DPhil Department of Geography February 2006 Contents Abstract Acknowledgements II Chapter One Introduction Chapter Two Methodology I: A genealogy of (bio )political contestation 45 Chapter Three Methodology II: Govemmentality, biopolitics and agonism 52 Chapter Four The demonstration 80 Chapter Five Human rights: bare life or life politics? 104 Chapter Six Testimony and the limits ofbiopolitical truth speech 135 Chapter Seven Conclusion 161 Appendix 163 References 180 A genealogy of (bio)political contestation during the reform of the Mental Health Act 1983 in England and Wales In 1997 the Department of Health announced their intention to reform the Mental Health Act 1983. Since publishing the first Green Paper in 1999, the proposed reforms have received major criticisms from virtually all 'stakeholders' in mental health care. This PhD offers a genealogy of (bio)political action during the process of reforming the Act. The focus is on the period from August 2002 to September 2003, with particular reference to the activities of self proclaimed 'service users' and 'survivors' in two independent protest groups: 'NO Force' and . Protest Against the Bill'. The methodological premise (chapters two and three) is born from something of a lacuna in post-Foucauldian governmentality studies which, although well posited, offer little in the way of advancing a genealogy of governmental contestation. My focus is twofold. Firstly, by advancing a (post)Foucauldian understanding of resistance - which, with respect to power, 'always comes first' (Deleuze 1988) - I aim to develop the relationship between 'biosociality' or 'life politics' (Rabinow 1996, Rose 200 I) and mental health law. -

Genealogy Is an Historical Perspective and Investigative Method, Which

International Encyclopaedia of Human Geography Genealogy, method (MS number: 443) Úna Crowley, Department of Geography and NIRSA, 16TF Hume Building, National University of Ireland, Maynooth, Co Kildare, Ireland. [email protected] 1 Key words: archaeology, discipline, discourse, Foucault, genealogy, knowledge, Nietzsche, power, social control, sexuality, subjectivity, truth. Glossary Discourse: a social boundary defining what can be said and what cannot be said Episteme: systems of thought and knowledge (or conceptual frameworks) which define a system of conceptual possibilities that determine the boundaries in a given period. Subjugated knowledge: knowledge that has been discounted, disqualified or low ranking. Synopsis Genealogy is a historical perspective and investigative method, which offers an intrinsic critique of the present. It provides people with the critical skills for analysing and uncovering the relationship between knowledge, power and the human subject in modern society and the conceptual tools to understand how their being has been shaped by historical forces. Genealogy works on the limits of what people think is possible, not only exposing those limits and confines but also revealing the spaces of freedom people can yet experience and the changes that can still be made (Foucault 1988). Genealogy as method derives from German philosophy, particularly the works of Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), but is most closely associated with French academic Michel Foucault (1926-24). Michel Foucault’s genealogical analyses challenge -

The Kingdom and the Glory: the Articulated Inoperativity of Power 235

The Kingdom and the Glory: The Articulated Inoperativity of Power 235 The Kingdom and the Glory: The Articulated Inoperativity of Power William Watkin* Abstract The starting point of this essay is the internal difference in the concept of power, the issue of authority and its relation to the act. The authority operates as both the assumed perfect coincidence of act and law, and as the pure externality of authority to law. This complex structure is the real essence of power in the West, government, whose main signature, The Kingdom and the Glory will go on to argue, has been that of oikonomia or economy. Finally, the paper will examine the notion of inoperativity, concept that reveals the total structure of the system. What we can say however is that until the signatures of power are themselves revealed in their inoperativity, the oft promised key to the totality of the Homo Sacer project, remains unintelligible. It is for this reason that The Kingdom and the Glory may come to be seen not only as one of Agamben’s most important statements, but as the fundamental work of political philosophy of our age. Keywords: power, authority, law, government, inoperativity. Resumen El punto de partida de este ensayo es la diferencia interna en el concepto de poder, la problemática de la autoridad y su relación con el acto. La autoridad opera a la vez como la coincidencia perfecta supuesto de acto y ley, y como la pura externalidad de autoridad a la ley. Esta compleja es la esencia real del poder en occidente, el gobierno, cuya signatura ha sido la economía, como El reino y la Gloria defenderá.