Goals and Objectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OPEN SPACE and RECREATION PLAN UPDATE - 2009 for Township of Green County of Sussex

OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN UPDATE - 2009 for Township of Green County of Sussex Compiled by The Land Conservancy with Township of Green of New Jersey Open Space Committee A nonprofit land trust May 2009 OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN UPDATE - 2009 for Township of Green County of Sussex Compiled by The Land Conservancy of Township of Green New Jersey with Open Space Committee a nonprofit land trust May 2009 OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN UPDATE - 2009 for Township of Green County of Sussex Produced by: The Land Conservancy of New Jersey Partners for Greener Communities Team: “Partnering with Communities to Preserve Natural Treasures” David Epstein, President Barbara Heskins Davis, AICP/P.P., Vice President, Programs Holly Szoke, Communications Director Kenneth Fung, GIS Manager Samantha Rothman, Planning Consultant Casey Dziuba, Planning Intern For further information please contact: The Land Conservancy of New Jersey Township of Green 19 Boonton Avenue Open Space Committee Boonton, NJ 07005 150 Kennedy Road (973) 541-1010 Andover, NJ 07821 Fax: (973) 541-1131 (908) 852-9333 www.tlc-nj.org Fax: (908) 852-1972 www.greentwp.com Copyright © 2009 All rights reserved Including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form without prior consent May 2009 . Acknowledgements The Land Conservancy of New Jersey wishes to acknowledge the following individuals and organizations for their help in providing information, guidance, and materials for the Green Township Open Space and Recreation Plan Update. Their contributions have been instrumental -

Passaic River Walk, Station-To-Station

Radburn PASSAIC RIVER WALK, STATION-TO-STATION Walking Route City Street or Path The Passaic River winds through a wide range of scenic, historical, industrial, and residential landscapes Passaic River on its ninety-mile course to the sea. Exploring the river in its entirety is nearly impossible on foot Train Station because only small sections have accessible parks or trail systems. A pedestrian must be ready Take a right here and for a journey that offers only occasional glimpses of the river, usually from bridge crossings, then shortly another right onto while moving through the neighborhoods that line its banks. This walk visits three majestic West Broadway and over the Passaic and moving places contained in a single day of walking: the Great Falls, the city of River. After passing Memorial Drive, turn left Paterson, and a precolonial stone weir. onto Broadway, and after one mile turn left onto Madison Avenue. The city of Paterson is built on a hill rounded on three The Walk: When you arrive at Paterson Station, walk to Market Street and take a sides by the Passaic River. Walking down Madison Avenue gives you left toward the one tall modern glass building. As you walk down Market Street, an understanding of the topography. There are also buses frequently foot traffic increases and historical architecture abounds. Market Street bends at running down Madison if you want a lift. After about a mile, at Fourth Washington Street, and in the distance you can see the start of the mill district Avenue, turn right and walk down the hill toward the Home Depot. -

Annual Report of the State Geologist for the Year 1877

NEW JERSEY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGICALSURVEYOF IN:LWJERSELz r ANNUAL REPORT OF TIIE STATEGEOLOGIST FOB TH-EYEAR IS77. TREe's'TON..N'. J, : _AAR. DAy & _'AAR, PRINTERS. NEW JERSEY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY NEW JERSEY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BOARD OF MANAGERS. His Excellency, JOSEPH D. BEDLE, Governor, and ex-off_eio Presi- dent of the Board ............................................................ Trenton. L CONGRES_SIO_AL DISTRICT. CIIXRL_S E. ELm:R, Esq ........................................................ Bridgeton. ItoN. ANDREW K, HAY .......................................................... Winslow. II. CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT. I'[ON. "_VILLIAM PARRY ........................................................... Cinnamiuson. ' HON, H. S, LITTLE ................................................................. Trenton. 1II. CONGRESSlONAI_DISTRICT. HENRY AITKIN, Esq .............................................................. Elizabetll. ] JoHs VOUGI_T, M. D ............................................................. Freehold. IV. CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT. SELDE._ T. SORA_'TO.'_, Esq ..................................................... Oxford. TtlO.MAS LAWRE_CE_ Esq...'. .................................................... Hamburg. v. CO._GRF._IO.'CAL DISTRICT. HO.N'. AUGUSTUS W. CUTLER ................................................... Morristown. (_OL. BENJA,'III_ _-YCRIGG ....................................................... Pf189aic. VI, CO_GRF_SIONAL DISTRICT. WILLIAM M. FORCg_ Esq ...................................................... -

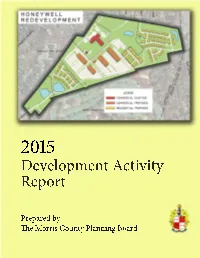

312006793-2015-Development-Activity-Report

On the Cover n the cover is a color rendering of the proposed redevelopment of the former Honeywell corporate headquarters lo- cated at the intersection of Park Avenue Oand Columbia Road in the Township of Morris. Be- fore redevelopment, the 147 acre Honeywell site con- tained 1,156,182-square feet in multiple buildings that were used for offi ce, laboratory and research. The approved general development plan subdi- vided the site into fi ve parcels. Excluding an ex- isting building to be retained by Honeywell, all of the existing structures on the site will be demol- ished. Two of the proposed parcels are limited to residential use only and will contain up to 235 townhomes of which 24 will be designated for af- fordable housing. Approximately 15 acres will be Honeywell campus 1995 dedicated for open space (southwest area of the site). The remaining two parcels will contain up to 900,000-square feet of non-residential uses (offi ce/ lab/research). The Honeywell Corporation will retain 185,000 square feet of existing buildings on one of these parcels and up to 715,000 square feet of new commercial Class A offi ce or lab space will be constructed on the other remaining parcel. K. Hovnanian will be developing the residential por- tion of the redevelopment while the Rockefeller Group will be developing the commercial portion. The close proximity to mass transit options as well as the proximity to Routes 24 and 287 add to the appeal of this site. The property is less than a mile from the New Jersey Transit Convent Station rail station (Morris & Essex Line) which provides rail service to New York City. -

SUSSEX County

NJ DEP - Historic Preservation Office Page 1 of 9 New Jersey and National Registers of Historic Places Last Update: 9/28/2021 SUSSEX County Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad Lackawanna Cutoff SUSSEX County Historic District (ID#3454) SHPO Opinion: 3/22/1994 Also located in: Andover Borough MORRIS County, Roxbury Township Andover Borough Historic District (ID#2591) SUSSEX County, Andover Borough SHPO Opinion: 10/22/1991 SUSSEX County, Andover Township SUSSEX County, Green Township 20 Brighton Avenue (ID#3453) SUSSEX County, Hopatcong Borough 20 Brighton Avenue SUSSEX County, Stanhope Borough SHPO Opinion: 9/11/1996 WARREN County, Blairstown Township WARREN County, Frelinghuysen Township Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad Lackawanna Cutoff WARREN County, Knowlton Township Historic District (ID#3454) SHPO Opinion: 3/22/1994 Morris Canal (ID#2784) See Main Entry / Filed Location: Existing and former bed of the Morris Canal SUSSEX County, Byram Township NR: 10/1/1974 (NR Reference #: 74002228) SR: 11/26/1973 Hole in the Wall Stone Arch Bridge (ID#2906) SHPO Opinion: 4/27/2004 Delaware, Lackawanna, & Western Railroad Sussex Branch over the (Extends from the Delaware River in Phillipsburg Town, Morris and Susses Turnpike west of US Route 206, north of Whitehall Warren County to the Hudson River in Jersey City, Hudson SHPO Opinion: 4/18/1995 County. SHPO Opinion extends period of significance for canal to its 1930 closure.) Pennsylvania-New Jersey Interconnection Bushkill to Roseland See Main Entry / Filed Location: Transmission -

Personal Rapid Transit (PRT) New Jersey

Personal Rapid Transit (PRT) for New Jersey By ORF 467 Transportation Systems Analysis, Fall 2004/05 Princeton University Prof. Alain L. Kornhauser Nkonye Okoh Mathe Y. Mosny Shawn Woodruff Rachel M. Blair Jeffery R Jones James H. Cong Jessica Blankshain Mike Daylamani Diana M. Zakem Darius A Craton Michael R Eber Matthew M Lauria Bradford Lyman M Martin-Easton Robert M Bauer Neset I Pirkul Megan L. Bernard Eugene Gokhvat Nike Lawrence Charles Wiggins Table of Contents: Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction to Personal Rapid Transit .......................................................................................... 3 New Jersey Coastline Summary .................................................................................................... 5 Burlington County (M. Mosney '06) ..............................................................................................6 Monmouth County (M. Bernard '06 & N. Pirkul '05) .....................................................................9 Hunterdon County (S. Woodruff GS .......................................................................................... 24 Mercer County (M. Martin-Easton '05) ........................................................................................31 Union County (B. Chu '05) ...........................................................................................................37 Cape May County (M. Eber '06) …...............................................................................................42 -

Master Pages Test

Library & Archives Book Catalog Passaic County Historical Society Museum ~ Library ~ Archives Lambert Castle, 3 Valley Road, Paterson, New Jersey 07503-2932 Phone: (973) 247-0085 • Fax: (973) 881-9434 email: [email protected] www.lambertcastle.org May 2019 PASSAIC COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY Library & Archives Book Catalog L.O.C. Call Number 100 Years of Collecting in America; The Story of Sotheby Parke Bernet N 5215 .N6 1984 Thomas E. Norton H.N. Abrams, 1984 108 Steps around Macclesfield: A Walker’s Guide DA 690 .M3 W4 1994 Andrew Wild Sigma Leisure, 1994 1637-1887. The Munson record. A Genealogical and Biographical Account of CS 71 .M755 1895 Vol. 1 Captain Thomas Munson (A Pioneer of Hartford and New Haven) and his Descendants Munson Association, 1895 1637-1887. The Munson record. A Genealogical and Biographical Account of CS 71 .M755 1895 Vol. 2 Captain Thomas Munson (A Pioneer of Hartford and New Haven) and his Descendants Munson Association, 1895 1736-1936 Historical Discourse Delivered at the Celebration of the Two-Hundredth BX 9531 .P7 K4 1936 Anniversary of the First Reformed Church of Pompton Plains, New Jersey Eugene H. Keator, 1936 1916 Photographic Souvenir of Hawthorne, New Jersey F144.H6 1916 S. Gordon Hunt, 1916 1923 Catalogue of Victor Records, Victor Talking Machine Company ML 156 .C572 1923 Museums Council of New Jersey, 1923 25 years of the Jazz Room at William Paterson University ML 3508 .T8 2002 Joann Krivin; William Paterson University of New Jersey William Paterson University, 2002 25th Anniversary of the City of Clifton Exempt Firemen’s Association TH 9449 .C8 B7 1936 1936 300th Anniversary of the Bergen Reformed Church – Old Bergen 1660-1960 BX 9531 .J56 B4 1960 Jersey City, NJ: Old Bergen Church of Jersey City, New Jersey Bergen Reformed Church, 1960 50th Anniversary, Hawthorne, New Jersey, 1898-1948 F 144. -

Sussex County Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN for the County of Sussex “People and Nature Together” Compiled by Morris Land Conservancy with the Sussex County Open Space Committee September 30, 2003 County of Sussex Open Space and Recreation Plan produced by Morris Land Conservancy’s Partners for Greener Communities team: David Epstein, Executive Director Laura Szwak, Assistant Director Barbara Heskins Davis, Director of Municipal Programs Robert Sheffield, Planning Manager Tanya Nolte, Mapping Manager Sandy Urgo, Land Preservation Specialist Anne Bowman, Land Acquisition Administrator Holly Szoke, Communications Manager Letty Lisk, Office Manager Student Interns: Melissa Haupt Brian Henderson Brian Licinski Ken Sicknick Erin Siek Andrew Szwak Dolce Vieira OPEN SPACE AND RECREATION PLAN for County of Sussex “People and Nature Together” Compiled by: Morris Land Conservancy a nonprofit land trust with the County of Sussex Open Space Advisory Committee September 2003 County of Sussex Board of Chosen Freeholders Harold J. Wirths, Director Joann D’Angeli, Deputy Director Gary R. Chiusano, Member Glen Vetrano, Member Susan M. Zellman, Member County of Sussex Open Space Advisory Committee Austin Carew, Chairperson Glen Vetrano, Freeholder Liaison Ray Bonker Louis Cherepy Libby Herland William Hookway Tom Meyer Barbara Rosko Eric Snyder Donna Traylor Acknowledgements Morris Land Conservancy would like to acknowledge the following individuals and organizations for their help in providing information, guidance, research and mapping materials for the County of -

Wallkill River National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan February 2009 This Blue Goose, Designed by J.N

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Wallkill River National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan February 2009 This blue goose, designed by J.N. “Ding” Darling, has become the symbol of the National Wildlife Refuge System. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is the principal federal agency responsible for conserving, protecting, and enhancing fi sh, wildlife, plants, and their habitats for the continuing benefi t of the American people. The Service manages the 97-million acre National Wildlife Refuge System comprised of more than 548 national wildlife refuges and thousands of waterfowl production areas. It also operates 69 national fi sh hatcheries and 81 ecological services fi eld stations. The agency enforces federal wildlife laws, manages migratory bird populations, restores nationally signifi cant fi sheries, conserves and restores wildlife habitat such as wetlands, administers the Endangered Species Act, and helps foreign governments with their conservation efforts. It also oversees the Federal Assistance Program which distributes hundreds of millions of dollars in excise taxes on fi shing and hunting equipment to state wildlife agencies. Comprehensive Conservation Plans provide long term guidance for management decisions and set forth goals, objectives, and strategies needed to accomplish refuge purposes and identify the Service’s best estimate of future needs. These plans detail program planning levels that are sometimes substantially above current budget allocations and, as such, are primarily for Service strategic planning and program prioritization purposes. The plans do not constitute a commitment for staffi ng increases, operational and maintenance increases, or funding for future land acquisition. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Wallkill River National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan February 2009 Submitted by: Edward Henry Date Refuge Manager Wallkill River National Wildlife Refuge Concurrence by: Janet M. -

Guide to the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad Records

Guide to the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad Records NMAH.AC.1074 Alison Oswald 2018 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Historical........................................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Business Records, 1903-1966.................................................................. 5 Series 2: Drawings, 1878-1971................................................................................ 6 Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad Records NMAH.AC.1074 Collection Overview Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Title: -

Transportation Trips, Excursions, Special Journeys, Outings, Tours, and Milestones In, To, from Or Through New Jersey

TRANSPORTATION TRIPS, EXCURSIONS, SPECIAL JOURNEYS, OUTINGS, TOURS, AND MILESTONES IN, TO, FROM OR THROUGH NEW JERSEY Bill McKelvey, Editor, Updated to Mon., Mar. 8, 2021 INTRODUCTION This is a reference work which we hope will be useful to historians and researchers. For those researchers wanting to do a deeper dive into the history of a particular event or series of events, copious resources are given for most of the fantrips, excursions, special moves, etc. in this compilation. You may find it much easier to search for the RR, event, city, etc. you are interested in than to read the entire document. We also think it will provide interesting, educational, and sometimes entertaining reading. Perhaps it will give ideas to future fantrip or excursion leaders for trips which may still be possible. In any such work like this there is always the question of what to include or exclude or where to draw the line. Our first thought was to limit this work to railfan excursions, but that soon got broadened to include rail specials for the general public and officials, special moves, trolley trips, bus outings, waterway and canal journeys, etc. The focus has been on such trips which operated within NJ; from NJ; into NJ from other states; or, passed through NJ. We have excluded regularly scheduled tourist type rides, automobile journeys, air trips, amusement park rides, etc. NOTE: Since many of the following items were taken from promotional literature we can not guarantee that each and every trip was actually operated. Early on the railways explored and promoted special journeys for the public as a way to improve their bottom line. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 , \Q''1 "" tfVOM fiSTA SHEET UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Plaster Mill AND/OR COMMON [LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 5QQ ft. south of inter SfttvH nn n-F Ma-i™ _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT 13th Stanhope — VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE New Jersey 034 Sue r AIT 037 HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT X_PUBLIC ^OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM XBUILDING(S) ...PRIVATE XUNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X.PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _ IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION . .,. see continuation £NO sheet —MILITARY OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Borough of Stanhope STREET & NUMBER 77 Main Street CITY. TOWN STATE Stanhoue VICINITY OF New Jersey 0 [LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. Sussex County STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Newton REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE DATE 1976 —FEDERAL ^_STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS ^^^ pf Protection 1^20 CITY, TOWN Trenton New Jersey DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE .EXCELLENT X-DETERIORATED —UNALTERED .X-ORIGINALSITE .GOOD _RUINS XALTERED _MOVED DATE. .FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The plaster mill in Stanhope, constructed in the early 1800's as a mill building, was converted into iron works tenant housing in ca. 1840. It is a 3 1/2 story mill structure that is built into a bank so that only 1 1/2 stories are above ground on the northwest side.