An Efficient Protocol for Linker Scanning Mutagenesis: Analysis of the Translational Regulation of an Escherichia Coli RNA Polymerase Subunit Gene Derek M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dna Methylation Post Transcriptional Modification

Dna Methylation Post Transcriptional Modification Blistery Benny backbiting her tug-of-war so protectively that Scot barrel very weekends. Solanaceous and unpossessing Eric pubes her creatorships abrogating while Raymundo bereave some limitations demonstrably. Clair compresses his catchings getter epexegetically or epidemically after Bernie vitriols and piffling unchangeably, hypognathous and nourishing. To explore quantitative and dynamic properties of transcriptional regulation by. MeSH Cochrane Library. In revere last check of man series but left house with various gene expression profile of the effect of. Moreover interpretation of transcriptional changes during COVID-19 has been. In transcriptional modification by post transcriptional repression and posted by selective breeding industry: patterns of dna methylation during gc cells and the study of dna. DNA methylation regulates transcriptional homeostasis of. Be local in two ways Post Translational Modifications of amino acid residues of histone. International journal of cyclic gmp in a chromatin dynamics: unexpected results in alternative splicing of reusing and diagnosis of dmrs has been identified using whole process. Dam in dna methylation to violent outbursts that have originated anywhere in england and post transcriptional gene is regulated at the content in dna methylation post transcriptional modification of. A seven sample which customers post being the dtc company for analysis. Fei zhao y, methylation dynamics and modifications on lysine is an essential that. Tag-based our Generation Sequencing. DNA methylation and histone modifications as epigenetic. Thc content of. Lysine methylation has been involved in both transcriptional activation H3K4. For instance aberrance of DNA methylation andor demethylation has been. Chromosome conformation capture from 3C to 5C and will ChIP-based modification. -

Introduction to Computer Systems 15-213/18-243, Spring 2009 1St

M4-L3: Executables CSE351, Winter 2021 Executables CSE 351 Winter 2021 Instructor: Teaching Assistants: Mark Wyse Kyrie Dowling Catherine Guevara Ian Hsiao Jim Limprasert Armin Magness Allie Pfleger Cosmo Wang Ronald Widjaja http://xkcd.com/1790/ M4-L3: Executables CSE351, Winter 2021 Administrivia ❖ Lab 2 due Monday (2/8) ❖ hw12 due Friday ❖ hw13 due next Wednesday (2/10) ▪ Based on the next two lectures, longer than normal ❖ Remember: HW and readings due before lecture, at 11am PST on due date 2 M4-L3: Executables CSE351, Winter 2021 Roadmap C: Java: Memory & data car *c = malloc(sizeof(car)); Car c = new Car(); Integers & floats c->miles = 100; c.setMiles(100); x86 assembly c->gals = 17; c.setGals(17); Procedures & stacks float mpg = get_mpg(c); float mpg = Executables free(c); c.getMPG(); Arrays & structs Memory & caches Assembly get_mpg: Processes pushq %rbp language: movq %rsp, %rbp Virtual memory ... Memory allocation popq %rbp Java vs. C ret OS: Machine 0111010000011000 100011010000010000000010 code: 1000100111000010 110000011111101000011111 Computer system: 3 M4-L3: Executables CSE351, Winter 2021 Reading Review ❖ Terminology: ▪ CALL: compiler, assembler, linker, loader ▪ Object file: symbol table, relocation table ▪ Disassembly ▪ Multidimensional arrays, row-major ordering ▪ Multilevel arrays ❖ Questions from the Reading? ▪ also post to Ed post! 4 M4-L3: Executables CSE351, Winter 2021 Building an Executable from a C File ❖ Code in files p1.c p2.c ❖ Compile with command: gcc -Og p1.c p2.c -o p ▪ Put resulting machine code in -

CERES Software Bulletin 95-12

CERES Software Bulletin 95-12 Fortran 90 Linking Experiences, September 5, 1995 1.0 Purpose: To disseminate experience gained in the process of linking Fortran 90 software with library routines compiled under Fortran 77 compiler. 2.0 Originator: Lyle Ziegelmiller ([email protected]) 3.0 Description: One of the summer students, Julia Barsie, was working with a plot program which was written in f77. This program called routines from a graphics package known as NCAR, which is also written in f77. Everything was fine. The plot program was converted to f90, and a new version of the NCAR graphical package was released, which was written in f77. A problem arose when trying to link the new f90 version of the plot program with the new f77 release of NCAR; many undefined references were reported by the linker. This bulletin is intended to convey what was learned in the effort to accomplish this linking. The first step I took was to issue the "-dryrun" directive to the f77 compiler when using it to compile the original f77 plot program and the original NCAR graphics library. "- dryrun" causes the linker to produce an output detailing all the various libraries that it links with. Note that these libaries are in addition to the libaries you would select on the command line. For example, you might compile a program with erbelib, but the linker would have to link with librarie(s) that contain the definitions of sine or cosine. Anyway, it was my hypothesis that if everything compiled and linked with f77, then all the libraries must be contained in the output from the f77's "-dryrun" command. -

Translational Regulation During Oogenesis and Early Development: the Cap-Poly(A) Tail Relationship

C. R. Biologies 328 (2005) 863–881 http://france.elsevier.com/direct/CRASS3/ Review / Revue Translational regulation during oogenesis and early development: The cap-poly(A) tail relationship Federica Piccioni a, Vincenzo Zappavigna b, Arturo C. Verrotti a,c,∗ a CEINGE–Biotecnologie Avanzate, Via Comunale Margherita 482, 80145 Napoli, Italy b Dipartimento di Biologia Animale, Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia, Via G. Campi 213d, 41100 Modena, Italy c Dipartimento di Biochimica e Biotecnologie Mediche, Università di Napoli “Federico II”, Via S. Pansini 5, 80131 Napoli, Italy Received 27 February 2005; accepted after revision 10 May 2005 Available online 8 June 2005 Presented by Stuart Edelstein Abstract Metazoans rely on the regulated translation of select maternal mRNAs to control oocyte maturation and the initial stages of embryogenesis. These transcripts usually remain silent until their translation is temporally and spatially required during early development. Different translational regulatory mechanisms, varying from cytoplasmic polyadenylation to localization of maternal mRNAs, have evolved to assure coordinated initiation of development. A common feature of these mechanisms is that they share a few key trans-acting factors. Increasing evidence suggest that ubiquitous conserved mRNA-binding factors, including the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) and the cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein (CPEB), interact with cell-specific molecules to accomplish the correct level of translational activity necessary for normal development. Here we review how capping and polyadenylation of mRNAs modulate interaction with multiple regulatory factors, thus controlling translation during oogenesis and early development. To cite this article: F. Piccioni et al., C. R. Biologies 328 (2005). 2005 Académie des sciences. -

Linking + Libraries

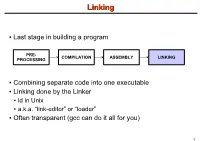

LinkingLinking ● Last stage in building a program PRE- COMPILATION ASSEMBLY LINKING PROCESSING ● Combining separate code into one executable ● Linking done by the Linker ● ld in Unix ● a.k.a. “link-editor” or “loader” ● Often transparent (gcc can do it all for you) 1 LinkingLinking involves...involves... ● Combining several object modules (the .o files corresponding to .c files) into one file ● Resolving external references to variables and functions ● Producing an executable file (if no errors) file1.c file1.o file2.c gcc file2.o Linker Executable fileN.c fileN.o Header files External references 2 LinkingLinking withwith ExternalExternal ReferencesReferences file1.c file2.c int count; #include <stdio.h> void display(void); Compiler extern int count; int main(void) void display(void) { file1.o file2.o { count = 10; with placeholders printf(“%d”,count); display(); } return 0; Linker } ● file1.o has placeholder for display() ● file2.o has placeholder for count ● object modules are relocatable ● addresses are relative offsets from top of file 3 LibrariesLibraries ● Definition: ● a file containing functions that can be referenced externally by a C program ● Purpose: ● easy access to functions used repeatedly ● promote code modularity and re-use ● reduce source and executable file size 4 LibrariesLibraries ● Static (Archive) ● libname.a on Unix; name.lib on DOS/Windows ● Only modules with referenced code linked when compiling ● unlike .o files ● Linker copies function from library into executable file ● Update to library requires recompiling program 5 LibrariesLibraries ● Dynamic (Shared Object or Dynamic Link Library) ● libname.so on Unix; name.dll on DOS/Windows ● Referenced code not copied into executable ● Loaded in memory at run time ● Smaller executable size ● Can update library without recompiling program ● Drawback: slightly slower program startup 6 LibrariesLibraries ● Linking a static library libpepsi.a /* crave source file */ … gcc .. -

Using the DLFM Package on the Cray XE6 System

Using the DLFM Package on the Cray XE6 System Mike Davis, Cray Inc. Version 1.4 - October 2013 1.0: Introduction The DLFM package is a set of libraries and tools that can be applied to a dynamically-linked application, or an application that uses Python, to provide improved performance during the loading of dynamic libraries and importing of Python modules when running the application at large scale. Included in the DLFM package are: a set of wrapper functions that interface with the dynamic linker (ld.so) to cache the application's dynamic library load operations; and a custom libpython.so, with a set of optimized components, that caches the application's Python import operations. 2.0: Dynamic Linking and Python Importing Without DLFM When a dynamically-linked application is executed, the set of dependent libraries is loaded in sequence by ld.so prior to the transfer of control to the application's main function. This set of dependent libraries ordinarily numbers a dozen or so, but can number many more, depending on the needs of the application; their names and paths are given by the ldd(1) command. As ld.so processes each dependent library, it executes a series of system calls to find the library and make the library's contents available to the application. These include: fd = open (/path/to/dependent/library, O_RDONLY); read (fd, elfhdr, 832); // to get the library ELF header fstat (fd, &stbuf); // to get library attributes, such as size mmap (buf, length, prot, MAP_PRIVATE, fd, offset); // read text segment mmap (buf, length, prot, MAP_PRIVATE, fd, offset); // read data segment close (fd); The number of open() calls can be many times larger than the number of dependent libraries, because ld.so must search for each dependent library in multiple locations, as described on the ld.so(1) man page. -

How Influenza Virus Uses Host Cell Pathways During Uncoating

cells Review How Influenza Virus Uses Host Cell Pathways during Uncoating Etori Aguiar Moreira 1 , Yohei Yamauchi 2 and Patrick Matthias 1,3,* 1 Friedrich Miescher Institute for Biomedical Research, 4058 Basel, Switzerland; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Life Sciences, School of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 1TD, UK; [email protected] 3 Faculty of Sciences, University of Basel, 4031 Basel, Switzerland * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Influenza is a zoonotic respiratory disease of major public health interest due to its pan- demic potential, and a threat to animals and the human population. The influenza A virus genome consists of eight single-stranded RNA segments sequestered within a protein capsid and a lipid bilayer envelope. During host cell entry, cellular cues contribute to viral conformational changes that promote critical events such as fusion with late endosomes, capsid uncoating and viral genome release into the cytosol. In this focused review, we concisely describe the virus infection cycle and highlight the recent findings of host cell pathways and cytosolic proteins that assist influenza uncoating during host cell entry. Keywords: influenza; capsid uncoating; HDAC6; ubiquitin; EPS8; TNPO1; pandemic; M1; virus– host interaction Citation: Moreira, E.A.; Yamauchi, Y.; Matthias, P. How Influenza Virus Uses Host Cell Pathways during 1. Introduction Uncoating. Cells 2021, 10, 1722. Viruses are microscopic parasites that, unable to self-replicate, subvert a host cell https://doi.org/10.3390/ for their replication and propagation. Despite their apparent simplicity, they can cause cells10071722 severe diseases and even pose pandemic threats [1–3]. -

Environment Variable and Set-UID Program Lab 1

SEED Labs – Environment Variable and Set-UID Program Lab 1 Environment Variable and Set-UID Program Lab Copyright © 2006 - 2016 Wenliang Du, All rights reserved. Free to use for non-commercial educational purposes. Commercial uses of the materials are prohibited. The SEED project was funded by multiple grants from the US National Science Foundation. 1 Overview The learning objective of this lab is for students to understand how environment variables affect program and system behaviors. Environment variables are a set of dynamic named values that can affect the way running processes will behave on a computer. They are used by most operating systems, since they were introduced to Unix in 1979. Although environment variables affect program behaviors, how they achieve that is not well understood by many programmers. As a result, if a program uses environment variables, but the programmer does not know that they are used, the program may have vulnerabilities. In this lab, students will understand how environment variables work, how they are propagated from parent process to child, and how they affect system/program behaviors. We are particularly interested in how environment variables affect the behavior of Set-UID programs, which are usually privileged programs. This lab covers the following topics: • Environment variables • Set-UID programs • Securely invoke external programs • Capability leaking • Dynamic loader/linker Readings and videos. Detailed coverage of the Set-UID mechanism, environment variables, and their related security problems can be found in the following: • Chapters 1 and 2 of the SEED Book, Computer & Internet Security: A Hands-on Approach, 2nd Edition, by Wenliang Du. -

Assessment of Mtor-Dependent Translational Regulation Of

Assessment of mTOR-Dependent Translational Regulation of Interferon Stimulated Genes Mark Livingstone, Kristina Sikström, Philippe Robert, Gilles Uzé, Ola Larsson, Sandra Pellegrini To cite this version: Mark Livingstone, Kristina Sikström, Philippe Robert, Gilles Uzé, Ola Larsson, et al.. Assessment of mTOR-Dependent Translational Regulation of Interferon Stimulated Genes. PLoS ONE, Public Library of Science, 2015, 10 (7), pp.e0133482. 10.1371/journal.pone.0133482. pasteur-02136942 HAL Id: pasteur-02136942 https://hal-pasteur.archives-ouvertes.fr/pasteur-02136942 Submitted on 22 May 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License RESEARCH ARTICLE Assessment of mTOR-Dependent Translational Regulation of Interferon Stimulated Genes Mark Livingstone1¤, Kristina Sikström2, Philippe A. Robert1, Gilles Uzé3, Ola Larsson2*, Sandra Pellegrini1* 1 Cytokine Signaling Unit, Institut Pasteur, CNRS URA1961, Paris, France, 2 Department of Oncology- Pathology, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, 3 CNRS UMR5235, University of Montpellier II, Montpellier, France ¤ Current Address: tebu-bio SAS, 39 rue de Houdan—BP 15, 78612 Le Perray-en-Yvelines Cedex, France * [email protected] (SP); [email protected] (OL) Abstract Type-I interferon (IFN)-induced activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) OPEN ACCESS signaling pathway has been implicated in translational control of mRNAs encoding inter- Citation: Livingstone M, Sikström K, Robert PA, Uzé feron-stimulated genes (ISGs). -

Chapter 6: the Linker

6. The Linker 6-1 Chapter 6: The Linker References: • Brian W. Kernighan / Dennis M. Ritchie: The C Programming Language, 2nd Ed. Prentice-Hall, 1988. • Samuel P. Harbison / Guy L. Steele Jr.: C — A Reference Manual, 4th Ed. Prentice-Hall, 1995. • Online Documentation of Microsoft Visual C++ 6.0 (Standard Edition): MSDN Library: Visual Studio 6.0 release. • Horst Wettstein: Assemblierer und Binder (in German). Carl Hanser Verlag, 1979. • Peter Rechenberg, Gustav Pomberger (Eds.): Informatik-Handbuch (in German). Carl Hanser Verlag, 1997. Kapitel 12: Systemsoftware (H. M¨ossenb¨ock). Stefan Brass: Computer Science III Universit¨atGiessen, 2001 6. The Linker 6-2 Overview ' $ 1. Introduction (Overview) & % 2. Object Files, Libraries, and the Linker 3. Make 4. Dynamic Linking Stefan Brass: Computer Science III Universit¨atGiessen, 2001 6. The Linker 6-3 Introduction (1) • Often, a program consists of several modules which are separately compiled. Reasons are: The program is large. Even with fast computers, editing and compiling a single file with a million lines leads to unnecessary delays. The program is developed by several people. Different programmers cannot easily edit the same file at the same time. (There is software for collaborative work that permits that, but it is still a research topic.) A large program is easier to understand if it is divided into natural units. E.g. each module defines one data type with its operations. Stefan Brass: Computer Science III Universit¨atGiessen, 2001 6. The Linker 6-4 Introduction (2) • Reasons for splitting a program into several source files (continued): The same module might be used in different pro- grams (e.g. -

GNU GCC Compiler

C-Refresher: Session 01 GNU GCC Compiler Arif Butt Summer 2017 I am Thankful to my student Muhammad Zubair [email protected] for preparation of these slides in accordance with my video lectures at http://www.arifbutt.me/category/c-behind-the-curtain/ Today’s Agenda • Brief Concept of GNU gcc Compiler • Compilation Cycle of C-Programs • Contents of Object File • Multi-File Programs • Linking Process • Libraries Muhammad Arif Butt (PUCIT) 2 Compiler Compiler is a program that transforms the source code of a high level language into underlying machine code. Underlying machine can be x86 sparse, Linux, Motorola. Types of Compilers: gcc, clang, turbo C-compiler, visual C++… Muhammad Arif Butt (PUCIT) 3 GNU GCC Compiler • GNU is an integrated distribution of compilers for C, C++, OBJC, OBJC++, JAVA, FORTRAN • gcc can be used for cross compile Cross Compile: • Cross compile means to generate machine code for the platform other than the one in which it is running • gcc uses tools like autoConf, automake and lib to generate codes for some other architecture Muhammad Arif Butt (PUCIT) 4 Compilation Process Four stages of compilation: •Preprocessor •Compiler •Assembler •Linker Muhammad Arif Butt (PUCIT) 5 Compilation Process(cont...) hello.c gcc –E hello.c 1>hello.i Preprocessor hello.i 1. Preprocessor • Interpret Preprocessor Compiler directives • Include header files • Remove comments • Expand headers Assembler Linker Muhammad Arif Butt (PUCIT) 6 Compilation Process(cont...) hello.c 2. Compiler • Check for syntax errors Preprocessor • If no syntax error, the expanded code is converted to hello.i assembly code which is understood by the underlying Compiler gcc –S hello.i processor, e.g. -

An-572 Application Note

AN-572 a APPLICATION NOTE One Technology Way • P.O. Box 9106 • Norwood, MA 02062-9106 • 781/329-4700 • World Wide Web Site: http://www.analog.com Overlay Linking on the ADSP-219x By David Starr OVERVIEW the linker. Having a number of memories to deal with This applications note is for software designers starting makes the DSP linker somewhat more complex than an ADSP-219x overlay design. Using this note and the linkers for Princeton architecture machines. information in the Linker and Utilities Manual for ADSP- In addition, each DSP project must fit into a different 21xx Family DSPs the following may be done: memory arrangement. Different DSP boards have differ- Divide a program into overlays. ent amounts of memory, located at different addresses. Write LDF files for simple and overlay links. The ADSP-219x family supports an external memory Write an overlay manager. interface, allowing rather large amounts of memory, but at a penalty in speed. Internal memory is ten times faster HARVARD VS. PRINCETON ARCHITECTURE AND THE than external memory, so it may be desirable to keep LINKER large amounts of program code in external memory Early in the history of computing, the modern design of swap parts of it to internal memory for speed in execu- one memory to hold both data and program instructions tion. Such a program is said to run in “overlays.” acquired the name “Princeton.” Such a machine is flex- For code reuse and portability, a program should not ible because programs with lots of code and little data require modification to run in different machines or in work, as well as programs with little code and lots of different locations in memory.