Linker Script Guide Emprog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Computer Systems 15-213/18-243, Spring 2009 1St

M4-L3: Executables CSE351, Winter 2021 Executables CSE 351 Winter 2021 Instructor: Teaching Assistants: Mark Wyse Kyrie Dowling Catherine Guevara Ian Hsiao Jim Limprasert Armin Magness Allie Pfleger Cosmo Wang Ronald Widjaja http://xkcd.com/1790/ M4-L3: Executables CSE351, Winter 2021 Administrivia ❖ Lab 2 due Monday (2/8) ❖ hw12 due Friday ❖ hw13 due next Wednesday (2/10) ▪ Based on the next two lectures, longer than normal ❖ Remember: HW and readings due before lecture, at 11am PST on due date 2 M4-L3: Executables CSE351, Winter 2021 Roadmap C: Java: Memory & data car *c = malloc(sizeof(car)); Car c = new Car(); Integers & floats c->miles = 100; c.setMiles(100); x86 assembly c->gals = 17; c.setGals(17); Procedures & stacks float mpg = get_mpg(c); float mpg = Executables free(c); c.getMPG(); Arrays & structs Memory & caches Assembly get_mpg: Processes pushq %rbp language: movq %rsp, %rbp Virtual memory ... Memory allocation popq %rbp Java vs. C ret OS: Machine 0111010000011000 100011010000010000000010 code: 1000100111000010 110000011111101000011111 Computer system: 3 M4-L3: Executables CSE351, Winter 2021 Reading Review ❖ Terminology: ▪ CALL: compiler, assembler, linker, loader ▪ Object file: symbol table, relocation table ▪ Disassembly ▪ Multidimensional arrays, row-major ordering ▪ Multilevel arrays ❖ Questions from the Reading? ▪ also post to Ed post! 4 M4-L3: Executables CSE351, Winter 2021 Building an Executable from a C File ❖ Code in files p1.c p2.c ❖ Compile with command: gcc -Og p1.c p2.c -o p ▪ Put resulting machine code in -

The GNU Linker

The GNU linker ld (GNU Binutils) Version 2.37 Steve Chamberlain Ian Lance Taylor Red Hat Inc [email protected], [email protected] The GNU linker Edited by Jeffrey Osier ([email protected]) Copyright c 1991-2021 Free Software Foundation, Inc. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.3 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, with no Front-Cover Texts, and with no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled \GNU Free Documentation License". i Table of Contents 1 Overview :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 1 2 Invocation ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 3 2.1 Command-line Options ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 3 2.1.1 Options Specific to i386 PE Targets :::::::::::::::::::::: 40 2.1.2 Options specific to C6X uClinux targets :::::::::::::::::: 47 2.1.3 Options specific to C-SKY targets :::::::::::::::::::::::: 48 2.1.4 Options specific to Motorola 68HC11 and 68HC12 targets :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 48 2.1.5 Options specific to Motorola 68K target :::::::::::::::::: 48 2.1.6 Options specific to MIPS targets ::::::::::::::::::::::::: 49 2.1.7 Options specific to PDP11 targets :::::::::::::::::::::::: 49 2.2 Environment Variables :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 50 3 Linker Scripts:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 51 3.1 Basic Linker Script Concepts :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 51 3.2 Linker Script -

CERES Software Bulletin 95-12

CERES Software Bulletin 95-12 Fortran 90 Linking Experiences, September 5, 1995 1.0 Purpose: To disseminate experience gained in the process of linking Fortran 90 software with library routines compiled under Fortran 77 compiler. 2.0 Originator: Lyle Ziegelmiller ([email protected]) 3.0 Description: One of the summer students, Julia Barsie, was working with a plot program which was written in f77. This program called routines from a graphics package known as NCAR, which is also written in f77. Everything was fine. The plot program was converted to f90, and a new version of the NCAR graphical package was released, which was written in f77. A problem arose when trying to link the new f90 version of the plot program with the new f77 release of NCAR; many undefined references were reported by the linker. This bulletin is intended to convey what was learned in the effort to accomplish this linking. The first step I took was to issue the "-dryrun" directive to the f77 compiler when using it to compile the original f77 plot program and the original NCAR graphics library. "- dryrun" causes the linker to produce an output detailing all the various libraries that it links with. Note that these libaries are in addition to the libaries you would select on the command line. For example, you might compile a program with erbelib, but the linker would have to link with librarie(s) that contain the definitions of sine or cosine. Anyway, it was my hypothesis that if everything compiled and linked with f77, then all the libraries must be contained in the output from the f77's "-dryrun" command. -

The “Stabs” Debug Format

The \stabs" debug format Julia Menapace, Jim Kingdon, David MacKenzie Cygnus Support Cygnus Support Revision TEXinfo 2017-08-23.19 Copyright c 1992{2021 Free Software Foundation, Inc. Contributed by Cygnus Support. Written by Julia Menapace, Jim Kingdon, and David MacKenzie. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.3 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, with no Front-Cover Texts, and with no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled \GNU Free Documentation License". i Table of Contents 1 Overview of Stabs ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 1 1.1 Overview of Debugging Information Flow ::::::::::::::::::::::: 1 1.2 Overview of Stab Format ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 1 1.3 The String Field :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 2 1.4 A Simple Example in C Source ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 3 1.5 The Simple Example at the Assembly Level ::::::::::::::::::::: 4 2 Encoding the Structure of the Program ::::::: 7 2.1 Main Program :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 7 2.2 Paths and Names of the Source Files :::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 7 2.3 Names of Include Files:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 8 2.4 Line Numbers :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 9 2.5 Procedures ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 9 2.6 Nested Procedures::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 11 2.7 Block Structure -

The IAR XLINK Linker™ and IAR XLIB Librarian™ Reference Guide

IAR Linker and Library To o l s Reference Guide Version 4.60 XLINK-460G COPYRIGHT NOTICE © Copyright 1987–2007 IAR Systems. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced without the prior written consent of IAR Systems. The software described in this document is furnished under a license and may only be used or copied in accordance with the terms of such a license. DISCLAIMER The information in this document is subject to change without notice and does not represent a commitment on any part of IAR Systems. While the information contained herein is assumed to be accurate, IAR Systems assumes no responsibility for any errors or omissions. In no event shall IAR Systems, its employees, its contractors, or the authors of this document be liable for special, direct, indirect, or consequential damage, losses, costs, charges, claims, demands, claim for lost profits, fees, or expenses of any nature or kind. TRADEMARKS IAR, IAR Systems, IAR Embedded Workbench, IAR MakeApp, C-SPY, visualSTATE, From Idea To Target, IAR KickStart Kit and IAR PowerPac are trademarks or registered trademarks owned by IAR Systems AB. All other product names are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. EDITION NOTICE April 2007 Part number: XLINK-460G The IAR Linker and Library Tools Reference Guide replaces all versions of the IAR XLINK Linker™ and IAR XLIB Librarian™ Reference Guide. XLINK-460G Contents Tables ..................................................................................................................... -

Packet Structure Definition

xx Tektronix Logic Analyzer Online Help ZZZ PrintedHelpDocument *P077003206* 077-0032-06 Tektronix Logic Analyzer Online Help ZZZ PrintedHelpDocument www.tektronix.com 077-0032-06 Copyright © Tektronix. All rights reserved. Licensed software products are owned by Tektronix or its subsidiaries or suppliers, and are protected by national copyright laws and international treaty provisions. Tektronix products are covered by U.S. and foreign patents, issued and pending. Information in this publication supersedes that in all previously published material. Specifications and price change privileges reserved. TEKTRONIX and TEK are registered trademarks of Tektronix, Inc. D-Max, MagniVu, iView, iVerify, iCapture, iLink, PowerFlex, and TekLink are trademarks of Tektronix, Inc. 076-0113-06 077-0032-06 April 27, 2012 Contacting Tektronix Tektronix, Inc. 14150 SWKarlBraunDrive P.O. Box 500 Beaverton, OR 97077 USA For product information, sales, service, and technical support: In North America, call 1-800-833-9200. Worldwide, visit www.tektronix.com to find contacts in your area. Warranty Tektronix warrants that this product will be free from defects in materials and workmanship for a period of one (1) year from the date of shipment. If any such product proves defective during this warranty period, Tektronix, at its option, either will repair the defective product without charge for parts and labor, or will provide a replacement in exchange for the defective product. Parts, modules and replacement products used by Tektronix for warranty work may be new or reconditioned to like new performance. All replaced parts, modules and products become the property of Tektronix. In order to obtain service under this warranty, Customer must notify Tektronix of the defect before the expiration of the warranty period and make suitable arrangements for the performance of service. -

Linking + Libraries

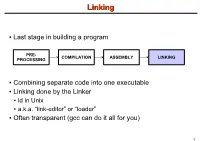

LinkingLinking ● Last stage in building a program PRE- COMPILATION ASSEMBLY LINKING PROCESSING ● Combining separate code into one executable ● Linking done by the Linker ● ld in Unix ● a.k.a. “link-editor” or “loader” ● Often transparent (gcc can do it all for you) 1 LinkingLinking involves...involves... ● Combining several object modules (the .o files corresponding to .c files) into one file ● Resolving external references to variables and functions ● Producing an executable file (if no errors) file1.c file1.o file2.c gcc file2.o Linker Executable fileN.c fileN.o Header files External references 2 LinkingLinking withwith ExternalExternal ReferencesReferences file1.c file2.c int count; #include <stdio.h> void display(void); Compiler extern int count; int main(void) void display(void) { file1.o file2.o { count = 10; with placeholders printf(“%d”,count); display(); } return 0; Linker } ● file1.o has placeholder for display() ● file2.o has placeholder for count ● object modules are relocatable ● addresses are relative offsets from top of file 3 LibrariesLibraries ● Definition: ● a file containing functions that can be referenced externally by a C program ● Purpose: ● easy access to functions used repeatedly ● promote code modularity and re-use ● reduce source and executable file size 4 LibrariesLibraries ● Static (Archive) ● libname.a on Unix; name.lib on DOS/Windows ● Only modules with referenced code linked when compiling ● unlike .o files ● Linker copies function from library into executable file ● Update to library requires recompiling program 5 LibrariesLibraries ● Dynamic (Shared Object or Dynamic Link Library) ● libname.so on Unix; name.dll on DOS/Windows ● Referenced code not copied into executable ● Loaded in memory at run time ● Smaller executable size ● Can update library without recompiling program ● Drawback: slightly slower program startup 6 LibrariesLibraries ● Linking a static library libpepsi.a /* crave source file */ … gcc .. -

Using the DLFM Package on the Cray XE6 System

Using the DLFM Package on the Cray XE6 System Mike Davis, Cray Inc. Version 1.4 - October 2013 1.0: Introduction The DLFM package is a set of libraries and tools that can be applied to a dynamically-linked application, or an application that uses Python, to provide improved performance during the loading of dynamic libraries and importing of Python modules when running the application at large scale. Included in the DLFM package are: a set of wrapper functions that interface with the dynamic linker (ld.so) to cache the application's dynamic library load operations; and a custom libpython.so, with a set of optimized components, that caches the application's Python import operations. 2.0: Dynamic Linking and Python Importing Without DLFM When a dynamically-linked application is executed, the set of dependent libraries is loaded in sequence by ld.so prior to the transfer of control to the application's main function. This set of dependent libraries ordinarily numbers a dozen or so, but can number many more, depending on the needs of the application; their names and paths are given by the ldd(1) command. As ld.so processes each dependent library, it executes a series of system calls to find the library and make the library's contents available to the application. These include: fd = open (/path/to/dependent/library, O_RDONLY); read (fd, elfhdr, 832); // to get the library ELF header fstat (fd, &stbuf); // to get library attributes, such as size mmap (buf, length, prot, MAP_PRIVATE, fd, offset); // read text segment mmap (buf, length, prot, MAP_PRIVATE, fd, offset); // read data segment close (fd); The number of open() calls can be many times larger than the number of dependent libraries, because ld.so must search for each dependent library in multiple locations, as described on the ld.so(1) man page. -

Architectural Support for Dynamic Linking Varun Agrawal, Abhiroop Dabral, Tapti Palit, Yongming Shen, Michael Ferdman COMPAS Stony Brook University

Architectural Support for Dynamic Linking Varun Agrawal, Abhiroop Dabral, Tapti Palit, Yongming Shen, Michael Ferdman COMPAS Stony Brook University Abstract 1 Introduction All software in use today relies on libraries, including All computer programs in use today rely on software standard libraries (e.g., C, C++) and application-specific libraries. Libraries can be linked dynamically, deferring libraries (e.g., libxml, libpng). Most libraries are loaded in much of the linking process to the launch of the program. memory and dynamically linked when programs are Dynamically linked libraries offer numerous benefits over launched, resolving symbol addresses across the applica- static linking: they allow code reuse between applications, tions and libraries. Dynamic linking has many benefits: It conserve memory (because only one copy of a library is kept allows code to be reused between applications, conserves in memory for all applications that share it), allow libraries memory (because only one copy of a library is kept in mem- to be patched and updated without modifying programs, ory for all the applications that share it), and allows enable effective address space layout randomization for libraries to be patched and updated without modifying pro- security [21], and many others. As a result, dynamic linking grams, among numerous other benefits. However, these is the predominant choice in all systems today [7]. benefits come at the cost of performance. For every call To facilitate dynamic linking of libraries, compiled pro- made to a function in a dynamically linked library, a trampo- grams include function call trampolines in their binaries. line is used to read the function address from a lookup table When a program is launched, the dynamic linker maps the and branch to the function, incurring memory load and libraries into the process address space and resolves external branch operations. -

CS429: Computer Organization and Architecture Linking I & II

CS429: Computer Organization and Architecture Linking I & II Dr. Bill Young Department of Computer Sciences University of Texas at Austin Last updated: April 5, 2018 at 09:23 CS429 Slideset 23: 1 Linking I A Simplistic Translation Scheme m.c ASCII source file Problems: Efficiency: small change Compiler requires complete re-compilation. m.s Modularity: hard to share common functions (e.g., printf). Assembler Solution: Static linker (or Binary executable object file linker). p (memory image on disk) CS429 Slideset 23: 2 Linking I Better Scheme Using a Linker Linking is the process of m.c a.c ASCII source files combining various pieces of code and data into a Compiler Compiler single file that can be loaded (copied) into m.s a.s memory and executed. Linking could happen at: Assembler Assembler compile time; Separately compiled m.o a.o load time; relocatable object files run time. Linker (ld) Must somehow tell a Executable object file module about symbols p (code and data for all functions defined in m.c and a.c) from other modules. CS429 Slideset 23: 3 Linking I Linking A linker takes representations of separate program modules and combines them into a single executable. This involves two primary steps: 1 Symbol resolution: associate each symbol reference throughout the set of modules with a single symbol definition. 2 Relocation: associate a memory location with each symbol definition, and modify each reference to point to that location. CS429 Slideset 23: 4 Linking I Translating the Example Program A compiler driver coordinates all steps in the translation and linking process. -

Environment Variable and Set-UID Program Lab 1

SEED Labs – Environment Variable and Set-UID Program Lab 1 Environment Variable and Set-UID Program Lab Copyright © 2006 - 2016 Wenliang Du, All rights reserved. Free to use for non-commercial educational purposes. Commercial uses of the materials are prohibited. The SEED project was funded by multiple grants from the US National Science Foundation. 1 Overview The learning objective of this lab is for students to understand how environment variables affect program and system behaviors. Environment variables are a set of dynamic named values that can affect the way running processes will behave on a computer. They are used by most operating systems, since they were introduced to Unix in 1979. Although environment variables affect program behaviors, how they achieve that is not well understood by many programmers. As a result, if a program uses environment variables, but the programmer does not know that they are used, the program may have vulnerabilities. In this lab, students will understand how environment variables work, how they are propagated from parent process to child, and how they affect system/program behaviors. We are particularly interested in how environment variables affect the behavior of Set-UID programs, which are usually privileged programs. This lab covers the following topics: • Environment variables • Set-UID programs • Securely invoke external programs • Capability leaking • Dynamic loader/linker Readings and videos. Detailed coverage of the Set-UID mechanism, environment variables, and their related security problems can be found in the following: • Chapters 1 and 2 of the SEED Book, Computer & Internet Security: A Hands-on Approach, 2nd Edition, by Wenliang Du. -

Chapter 6: the Linker

6. The Linker 6-1 Chapter 6: The Linker References: • Brian W. Kernighan / Dennis M. Ritchie: The C Programming Language, 2nd Ed. Prentice-Hall, 1988. • Samuel P. Harbison / Guy L. Steele Jr.: C — A Reference Manual, 4th Ed. Prentice-Hall, 1995. • Online Documentation of Microsoft Visual C++ 6.0 (Standard Edition): MSDN Library: Visual Studio 6.0 release. • Horst Wettstein: Assemblierer und Binder (in German). Carl Hanser Verlag, 1979. • Peter Rechenberg, Gustav Pomberger (Eds.): Informatik-Handbuch (in German). Carl Hanser Verlag, 1997. Kapitel 12: Systemsoftware (H. M¨ossenb¨ock). Stefan Brass: Computer Science III Universit¨atGiessen, 2001 6. The Linker 6-2 Overview ' $ 1. Introduction (Overview) & % 2. Object Files, Libraries, and the Linker 3. Make 4. Dynamic Linking Stefan Brass: Computer Science III Universit¨atGiessen, 2001 6. The Linker 6-3 Introduction (1) • Often, a program consists of several modules which are separately compiled. Reasons are: The program is large. Even with fast computers, editing and compiling a single file with a million lines leads to unnecessary delays. The program is developed by several people. Different programmers cannot easily edit the same file at the same time. (There is software for collaborative work that permits that, but it is still a research topic.) A large program is easier to understand if it is divided into natural units. E.g. each module defines one data type with its operations. Stefan Brass: Computer Science III Universit¨atGiessen, 2001 6. The Linker 6-4 Introduction (2) • Reasons for splitting a program into several source files (continued): The same module might be used in different pro- grams (e.g.