Shifting Sands in Sri Lanka - Mobilizing and Networking for Collective Action by River Sand Mining Affected Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distributed Modelling of Water Resources and Pollute Transport in Malwathu Oya Basin, Sri Lanka

-1DWQ6FL)RXQGDWLRQ6UL/DQND DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4038/jnsfsr.v47i3.9281 RESEARCH ARTICLE Distributed modelling of water resources and pollute transport in Malwathu Oya Basin, Sri Lanka A.C. Dahanayake * and R.L.H.L. Rajapakse 'HSDUWPHQWRI&LYLO(QJLQHHULQJ)DFXOW\RI(QJLQHHULQJ8QLYHUVLW\RI0RUDWXZD.DWXEHGGD0RUDWXZD Submitted: 04 April 2018; Revised: 11 April 2019; Accepted: 03 May 2019 Abstract: The Nachchaduwa sub-catchment (598.74 km 2) of the Malwathu Oya basin is seasonally stressed in the dry INTRODUCTION SHULRGVDQGLWVGRZQVWUHDPSDUWVXQGHUJRLQWHUPLWWHQWÀRRGV during monsoon seasons while the fate and behaviour of excess Water, being a vital natural resource to sustain all life QLWURJHQ 1 DQGSKRVSKRUXV 3 DGGHGWRWKHZDWHUZD\VGXH forms on earth, has now become a limited resource due to to agricultural fertilisers used in the upstream areas remain the adverse impacts of various natural and anthropogenic unresolved. This study incorporated the Water and Energy causes. Due to the increasing population and rapid 7UDQVIHU3URFHVVHV :(3 PRGHOWRDVVHVVWKHSUHVHQWVWDWXV urbanisation, the demand for water has been increasing of the catchment concerning water resources and pollutant drastically. Further, the quality of the available fresh transport. Results showed that the catchment response to the water resources has been deteriorating mainly due to UDLQIDOO LV KLJKO\ UHJXODWHG GXH WR UHVHUYRLU VWRUDJH H൵HFW pollution created by the anthropogenic activities in many XQJDXJHGEDVLQZLWKUHJXODWHGÀRZV 7KHDPRXQWVRI1DQG3 rivers in developing countries, which -

Fit.* IRRIGATION and MULTI-PURPOSE DEVELOPMENT

fit.* The Historic Jaya Ganga — built by King Dbatustna in tbi <>tb century AD to carry the waters of the Kala Wewa to the ancient city tanks of Anuradbapura, 57 miles away, while feeding a number of village tanks in its course. This channel is also famous for the gentle gradient of 6 ins. per mile for the first I7 miles and an average of 1 //. per mile throughout its length. Both tbeKalawewa andtbefiya Garga were restored in 1885 — 18 8 8 by the British, but not to their fullest capacities. New under the Mabaweli Diversion project, the Kill Wewa his been augmented and the Jaya Gingi improved to carry 1000 cusecs of water. The history of our country dates back to the 6th century B.C. When the legendary Vijaya landed in L->nka, he is believed to have found an island occupied by certain tribes who had already developed a rudimentary sys tem of irrigation. Tradition has it that Kuveni was spinning cotton on the bund of a small lake which was presumably part of this ancient system. The development of an ancient civilization which was entirely depen dent on an irrigation system that grew in size and complexity through the years is described in our written history. Many examples are available which demonstrate this systematic development of water and land re sources throughout the so-called dry zone of our country over very long periods of time. The development of a water supply and irrigation system around the city of Anuradhapuia may be taken as an example. -

Ecological Biogeography of Mangroves in Sri Lanka

Ceylon Journal of Science 46 (Special Issue) 2017: 119-125 DOI: http://doi.org/10.4038/cjs.v46i5.7459 RESEARCH ARTICLE Ecological biogeography of mangroves in Sri Lanka M.D. Amarasinghe1,* and K.A.R.S. Perera2 1Department of Botany, University of Kelaniya, Kelaniya 2Department of Botany, The Open University of Sri Lanka, Nawala, Nugegoda Received: 10/01/2017; Accepted: 10/08/2017 Abstract: The relatively low extent of mangroves in Sri extensively the observations are made and how reliable the Lanka supports 23 true mangrove plant species. In the last few identification of plants is, thus, rendering a considerable decades, more plant species that naturally occur in terrestrial and element of subjectivity. An attempt to reduce subjectivity freshwater habitats are observed in mangrove areas in Sri Lanka. in this respect is presented in the paper on “Historical Increasing freshwater input to estuaries and lagoons through biogeography of mangroves in Sri Lanka” in this volume. upstream irrigation works and altered rainfall regimes appear to have changed their species composition and distribution. This MATERIALS AND METHODS will alter the vegetation structure, processes and functions of Literature on mangrove distribution in Sri Lanka was mangrove ecosystems in Sri Lanka. The geographical distribution collated to analyze the gaps in knowledge on distribution/ of mangrove plant taxa in the micro-tidal coastal areas of Sri occurrence of true mangrove species. Recently published Lanka is investigated to have an insight into the climatic and information on mangrove distribution on the northern anthropogenic factors that can potentially influence the ecological and eastern coasts could not be found, most probably for biogeography of mangroves and sustainability of these mangrove the reason that these areas were inaccessible until the ecosystems. -

Annual Performance Report of the Ministry of Irrigation and Water

SO^a ^d S°rae/@^ ®g ^ 3 ^ 3 000 ^50da^u ^d ss^ 0 © ^ 0 0 m ® ®^3©i0^)^ SO §°0S SO^a & 0 i d ^ @ 0 ^ ^ iq t S i m g ^ u . Note Since original document prepared in English and translated to Sinhala/Tamil, in any discrepancy in words, English version shall be considered as correct. (g)fdlLJL| ^Lpso g^t)6H655TLD GlLonl^IiiJ60 ^ l u n r f l a a u u L l ® rflrhiaarnh / ^u51yp ^ d S lu j QLnuy51ffi(snjffi@ GIlditl^I 0uiLHTa«uuL_i_^rT6\) QLDrry5) 0uiLiiTuiJ6b 6j^rTeaQ ^rT0 (jprrswsrun@ ffimS55TLJULll_rT6\) ^rti]<£l6\)U Ljlp^l ff[fllUrT6O TQ ^6OT ffi0 ^LJU @ LD Message from the Secretary I am happy to present the Performance Report of the Ministry of Irrigation and Water Resources Management for the year 2011, having forged ahead to fulfill the mission and objectives of the Ministry, in the subjects and functions pertaining to the irrigation and water sub sectors. The year under review was eventful and we were able to take many progressive steps that will steer this sector to be more productive to serve the nation in the coming years. The capital investment programme of the Ministry had a workload of approximately Rs 20,000 million. This was a heavy development programme. We were on the path to achieve good progress, in spite of floods occurred in the beginning of the year and other constraints that had to be overcome during implementation. Steps were taken to remedy constraints such as staff shortages that existed, by new recruitments to the certain skilled technical grades but the shortage still prevails by large especially in the grades of Engineers, Engineering Assistants and other technical categories, which is being addressed by way of restructuring institutions, reviewing schemes of recruitments etc. -

River Sand Mining – Boon Or Bane

RIVER SAND MINING - BOON OR BANE? A synopsis of a series of national, provincial and local level dialogues on unregulated / illicit river sand mining Compiled by Ranjith Ratnayake Sri Lanka Water Partnership ? ? RIVER SAND MINING - BOON OR BANE? A synopsis of a series of national, provincial and local level dialogues on unregulated / illicit river sand mining Compiled by Ranjith Ratnayake Sri Lanka Water Partnership November 2008 River Sand Mining (Manual) Sand Removal from River Bed RIVER SAND BOON OR BANE? Preface Unregulated and illicit River Sand Mining (RSM) and its consequences with the related aspect of corruption, has been an issue that has constantly come up for discussion at forums organized by the Sri Lanka Water Partnership (SLWP) on Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) and other water related topics, starting with a Gender and Water dialogue held in Kurunegala in 2005. Two of the Area Water Partnerships (AWP) established for Deduru Oya (Deduru Oya Surakeeme Sanvidhanaya ) and the Maha Oya (Maha Oya Mithuro) have this as the priority issue, whilst three other AWP for Malwatu Oya , Upper Mahaveli and Nilwala highlight sand mining as needing urgent resolution. The SLWP after several local discussions organized a National Dialogue on River Sand and Clay Mining on 24th April 2006 in Colombo in collaboration with the Capacity Development Network (CapNet ) and the Network of Women Water Professionals ( NetWwater). The Hon; Minister of Science and Technology who was Chief Guest at this workshop attended by the relevant agencies and NGO agreed to set up a Ministerial Task Force for technological alternatives to river sand to be considered . -

An Economic Analysis of Intersectoral Water Allocation In

AN ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF INTERSECTORAL WATER ALLOCATION IN SOUTHEASTERN SRI LANKA BY SARATH PARAKRAMA WELIGAMAGE A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY School of Earth and Environmental Sciences AUGUST 2011 To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the dissertation of SARATH PARAKRAMA WELIGAMAGE find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. ___________________________________ Keith A. Blatner, Ph.D., Chair ___________________________________ C. Richard Shumway, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Jill J. McCluskey, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENT Earning a PhD from WSU fulfills a long held aspiration in my life to earn a doctorate from a US university. I thank all those who have contributed to my achieving this goal at Washington State University. Frank Rijsberman, Director General (2001-2007) of the International Water Management Institute (IWWI), was the key person behind meeting my aspiration to earn a PhD. His vision and passion for capacity building of scientific manpower in the South led to the initiation of the IWMI’s program for capacity building that supported my dissertation research. Frank also authorized the initial support for my PhD program. I thank Frank’s successor Colin Chartres, and David Molden, Interim Director General for continued support to me. At WSU, my major professor Keith Blatner was the key person behind fulfilling my goals. In addition to his unmatched knowledge spanning across many disciplines, Keith was a constant source of support and I also appreciate his compassion and empathy. I thank Richard Shumway for helping me fulfill my academic aspirations at a very high level. -

(Ifasina) Willeyi Horn (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) of Sri Lanka

JoTT COMMUNI C ATION 3(2): 1493-1505 The current occurrence, habitat and historical change in the distribution range of an endemic tiger beetle species Cicindela (Ifasina) willeyi Horn (Coleoptera: Cicindelidae) of Sri Lanka Chandima Dangalle 1, Nirmalie Pallewatta 2 & Alfried Vogler 3 1,2 Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, University of Colombo, Colombo 03, Sri Lanka 3 Department of Entomology, The Natural History Museum, London SW7 5BD, United Kingdom Email: 1 [email protected] (corresponding author), 2 [email protected], 3 [email protected] Date of publication (online): 26 February 2011 Abstract: The current occurrence, habitat and historical change in distributional range Date of publication (print): 26 February 2011 are studied for an endemic tiger beetle species, Cicindela (Ifasina) willeyi Horn of Sri ISSN 0974-7907 (online) | 0974-7893 (print) Lanka. At present, the species is only recorded from Maha Oya (Dehi Owita) and Handapangoda, and is absent from the locations where it previously occurred. The Editor: K.A. Subramanian current habitat of the species is explained using abiotic environmental factors of the Manuscript details: climate and soil recorded using standard methods. Morphology of the species is Ms # o2501 described by studying specimens using identification keys for the genus and comparing Received 02 July 2010 with specimens available at the National Museum of Colombo, Sri Lanka. The DNA Final received 29 December 2010 barcode of the species is elucidated using the mitochondrial CO1 gene sequence of Finally accepted 05 January 2011 eight specimens of Cicindela (Ifasina) willeyi. The study suggests that Maha Oya (Dehi Owita) and Handapangoda are suitable habitats. -

Water Balance Variability Across Sri Lanka for Assessing Agricultural and Environmental Water Use W.G.M

Agricultural Water Management 58 (2003) 171±192 Water balance variability across Sri Lanka for assessing agricultural and environmental water use W.G.M. Bastiaanssena,*, L. Chandrapalab aInternational Water Management Institute (IWMI), P.O. Box 2075, Colombo, Sri Lanka bDepartment of Meteorology, 383 Bauddaloka Mawatha, Colombo 7, Sri Lanka Abstract This paper describes a new procedure for hydrological data collection and assessment of agricultural and environmental water use using public domain satellite data. The variability of the annual water balance for Sri Lanka is estimated using observed rainfall and remotely sensed actual evaporation rates at a 1 km grid resolution. The Surface Energy Balance Algorithm for Land (SEBAL) has been used to assess the actual evaporation and storage changes in the root zone on a 10- day basis. The water balance was closed with a runoff component and a remainder term. Evaporation and runoff estimates were veri®ed against ground measurements using scintillometry and gauge readings respectively. The annual water balance for each of the 103 river basins of Sri Lanka is presented. The remainder term appeared to be less than 10% of the rainfall, which implies that the water balance is suf®ciently understood for policy and decision making. Access to water balance data is necessary as input into water accounting procedures, which simply describe the water status in hydrological systems (e.g. nation wide, river basin, irrigation scheme). The results show that the irrigation sector uses not more than 7% of the net water in¯ow. The total agricultural water use and the environmental systems usage is 15 and 51%, respectively of the net water in¯ow. -

Precipitation Trends in the Kalu Ganga Basin in Sri Lanka

January 2009 PRECIPITATION TRENDS IN THE KALU GANGA BASIN IN SRI LANKA A.D.Ampitiyawatta1, Shenglian Guo2 ABSTRACT Kalu Ganga basin is one of the most important river basins in Sri Lanka which receives very high rainfalls and has higher discharges. Due to its hydrological and topographical characteristics, the lower flood plain suffers from frequent floods and it affects socio- economic profile greatly. During the past several years, many researchers have investigated climatic changes of main river basins of the country, but no studies have been done on climatic changes in Kalu Ganga basin. Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate precipitation trends in Kalu Ganga basin. Annual and monthly precipitation trends were detected with Mann-Kendall statistical test. Negative trends of annual precipitation were found in all the analyzed rainfall gauging stations. As an average, -0.98 trend with the annual rainfall reduction of 12.03 mm/year was found. April and August were observed to have strong decreasing trends. July and November displayed strong increasing trends. In conclusion, whole the Kalu Ganga basin has a decreasing trend of annual precipitation and it is clear that slight climatic changes may have affected the magnitude and timing of the precipitation within the study area Key words: Kalu Ganga basin, precipitation, trend, Mann-Kendall statistical test. INTRODUCTION since the lower flood plain of Kalu Ganga is densely populated and it is a potential Kalu Ganga basin is the second largest area for rice production. During the past river basin in Sri Lanka covering 2766 km2 several years, attention has been paid to and much of the catchment is located in study on precipitation changes of main the highest rainfall area of the country, river basins of Sri Lanka. -

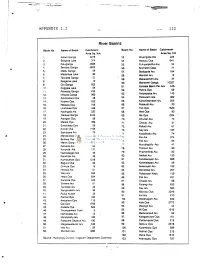

River Basins

APPENDIX I.I 122 River Basins Basin No Name of Basin Catchment Basin No. Name of Basin Catchment Area Sq. Km. Area Sq. Km 1. Kelani Ganga 2278 53. Miyangolla Ela 225 2. Bolgoda Lake 374 54. Maduru Oya 1541 3. Kaluganga 2688 55. Pulliyanpotha Aru 52 4. Bemota Ganga 6622 56. Kirimechi Odai 77 5. Madu Ganga 59 57. Bodigoda Aru 164 6. Madampe Lake 90 58. Mandan Aru 13 7. Telwatte Ganga 51 59. Makarachchi Aru 37 8. Ratgama Lake 10 60. Mahaweli Ganga 10327 9. Gin Ganga 922 61. Kantalai Basin Per Ara 445- 10. Koggala Lake 64 62. Panna Oya 69 11. Polwatta Ganga 233 12. Nilwala Ganga 960 63. Palampotta Aru 143 13. Sinimodara Oya 38 64. Pankulam Ara 382 14. Kirama Oya 223 65. Kanchikamban Aru 205 15. Rekawa Oya 755 66. Palakutti A/u 20 16. Uruhokke Oya 348 67. Yan Oya 1520 17. Kachigala Ara 220 68. Mee Oya 90 18. Walawe Ganga 2442 69. Ma Oya 1024 19. Karagan Oya 58 70. Churian A/u 74 20. Malala Oya 399 71. Chavar Aru 31 21. Embilikala Oya 59 72. Palladi Aru 61 22. Kirindi Oya 1165 73. Nay Ara 187 23. Bambawe Ara 79 74. Kodalikallu Aru 74 24. Mahasilawa Oya 13 75. Per Ara 374 25. Butawa Oya 38 76. Pali Aru 84 26. Menik Ganga 1272 27. Katupila Aru 86 77. Muruthapilly Aru 41 28. Kuranda Ara 131 78. Thoravi! Aru 90 29. Namadagas Ara 46 79. Piramenthal Aru 82 30. Karambe Ara 46 80. Nethali Aru 120 31. -

National Wetland DIRECTORY of Sri Lanka

National Wetland DIRECTORY of Sri Lanka Central Environmental Authority National Wetland Directory of Sri Lanka This publication has been jointly prepared by the Central Environmental Authority (CEA), The World Conservation Union (IUCN) in Sri Lanka and the International Water Management Institute (IWMI). The preparation and printing of this document was carried out with the financial assistance of the Royal Netherlands Embassy in Sri Lanka. i The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CEA, IUCN or IWMI concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the CEA, IUCN or IWMI. This publication has been jointly prepared by the Central Environmental Authority (CEA), The World Conservation Union (IUCN) Sri Lanka and the International Water Management Institute (IWMI). The preparation and publication of this directory was undertaken with financial assistance from the Royal Netherlands Government. Published by: The Central Environmental Authority (CEA), The World Conservation Union (IUCN) and the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), Colombo, Sri Lanka. Copyright: © 2006, The Central Environmental Authority (CEA), International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources and the International Water Management Institute. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. -

Study of Hydropower Optimization in Sri Lanka

JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY CEYLON ELECTRICITY BOARD(CEB) DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA STUDY OF HYDROPOWER OPTIMIZATION IN SRI LANKA FINAL REPORT SUMMARY FEBRUARY 2004 ELECTRIC POWER DEVELOPMENT CO., LTD. NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD. TOKYO, JAPAN The Main Dam Site (looking downstream) The Kehelgamu Oya Weir Site (looking upstream) The Powerhouse Site (looking from the right bank) The Study of Hydropower Optimization in Sri Lanka CONTENTS CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION .............................................................. CR - 1 Conclusion .................................................................................................................. CR - 1 Recommendation ......................................................................................................... CR - 5 PART I GENERAL 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 - 1 2. GENERAL FEATURES OF SRI LANKA ............................................................... 2 - 1 2.1 Topography ....................................................................................................... 2 - 1 2.2 Climate ............................................................................................................. 2 - 1 2.3 Government ....................................................................................................... 2 - 2 3. SOCIO-ECONOMY ................................................................................................. 3 - 1