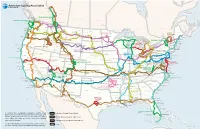

US Bike Route System: Surveys and Case Studies of Practices From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Route 66 (The Will Rogers Memorial Highway)

History of Route 66 History of Route 66 (the Will Rogers Memorial Highway) US Route 66 is also known as: • the Will Rogers Highway • the Main Street of America • the Mother Road It was established on November 11, 1926 as one of the original highways in the US Highway System, and became one of the most famous roads in the United States. Road signs were erected in 1927. It originally ran from Chicago, Illinois, through the states of Missouri, Kansas, New Mexico and Arizona before ending in Santa Monica, California, near Los Angeles, covering 2,448 miles or 3,940 kilometres. It was recognised in popular culture by the hit song ‘(Get Your Kicks on) Route 66’ in the 1960s. It features in John Steinbeck's classic American novel, The Grapes of Wrath (1939). Route 66 was a primary route for those who migrated west, especially during the Dust Bowl of the 1930s. The road supported the economies of the communities through which it passed. People doing business along the route became prosperous as the highway became more popular. The same people later fought to keep the highway alive in the face of the growing threat of being bypassed by the new Interstate Highway System. Route 66 underwent many improvements and realignments over its lifetime, but was officially removed from the United States Highway System on 26 June 1985. It had been entirely replaced by segments of the Interstate Highway System. Portions of the road that passed through Illinois, Missouri, New Mexico, and Arizona have been named ‘Historic Route 66’. -

In Creating the Ever-Growing Adventure Cycling Route Network

Route Network Jasper Edmonton BRITISH COLUMBIA Jasper NP ALBERTA Banff NP Banff GREAT PARKS NORTH Calgary Vancouver 741 mi Blaine SASKATCHEWAN North Cascades NP MANITOBA WASHINGTON PARKS Anacortes Sedro Woolley 866 mi Fernie Waterton Lakes Olympic NP NP Roosville Seattle Twisp Winnipeg Mt Rainier NEW Elma Sandpoint Cut Bank NP Whitefish BRUNSWICK Astoria Spokane QUEBEC WASHINGTON Glacier Great ONTARIO NP Voyageurs Saint John Seaside Falls Wolf Point NP Thunder Bay Portland Yakima Minot Fort Peck Isle Royale Missoula Williston NOVA SCOTIA Otis Circle NORTHERN TIER NP GREEN MAINE Salem Hood Clarkston Helena NORTH DAKOTA 4,293 mi MOUNTAINS Montreal Bar Harbor River MONTANA Glendive Dickinson 380 mi Kooskia Butte Walker Yarmouth Florence Bismarck Fargo Sault Ste Marie Sisters Polaris Three Forks Theodore NORTH LAKES Acadia NP McCall Roosevelt Eugene Duluth 1,160 mi Burlington NH Bend NP Conover VT Brunswick Salmon Bozeman Mackinaw DETROIT OREGON Billings ADIRONDACK PARK North Dalbo Escanaba City ALTERNATE 395 mi Portland Stanley West Yellowstone 505 mi Haverhill Devils Tower Owen Sound Crater Lake SOUTH DAKOTA Osceola LAKE ERIE Ticonderoga Portsmouth Ashland Ketchum NM Crescent City NP Minneapolis CONNECTOR Murphy Boise Yellowstone Rapid Stillwater Traverse City Toronto Grand Teton 507 mi Orchards Boston IDAHO HOT SPRINGS NP City Pierre NEW MA Redwood NP NP Gillette Midland WISCONSIN Albany RI Mt Shasta 518 mi WYOMING Wolf Marine Ithaca YORK Arcata Jackson MINNESOTA Manitowoc Ludington City Ft. Erie Buffalo IDAHO Craters Lake Windsor Locks -

USBRS Survey and Case Studies, July, 2013

U.S. Bike Route System: Surveys and Case Studies of Practices from Around the Country July 2013 U.S. Bike Route System Surveys & Case Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................ i Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ i State Coordinator Survey .................................................................................................................................... i Non‐Governmental Organization Survey .......................................................................................................... iv Case Studies ..................................................................................................................................................... iv Conclusion ........................................................................................................................................................ ix Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 1 State Coordinator Survey Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Accomplishments .................................................................................................................................. 2 -

BICYCLE ROUTE 66 Cycling UK Member Harry Lyons and Partner Celia Parker Got Their Kicks on the Iconic Tourist Trail from Chicago to Los Angeles

Details Where: USA Start/finish: Chicago to Los Angeles Distance: 2,500 miles approx Photos: Harry Lyons, Celia Parker 50 cycle JUNE/JULY 2019 ROUTE 66 GREAT RIDES HARRY LYONS & CELIA PARKER Cycling UK members Great Their tours have included North & Rides South America, Europe, and Asia BICYCLE ROUTE 66 Cycling UK member Harry Lyons and partner Celia Parker got their kicks on the iconic tourist trail from Chicago to Los Angeles he metal sign on the lamppost was battered Do it yourself Our first day on the road was a wet one, albeit and rusted, neglected like the historic house Getting there with compensations. We cycled past Anish T it marked, but I was thrilled. I was looking at Kapoor’s astonishing Cloud Gate (probably the most the Victorian red-brick house that Muddy Waters Our Bike Fridays popular of Chicago’s many public works of art) and had bought in 1954 in Chicago’s South Side. pack down into hard the Crown Fountains, with their ever-changing, We’d flown into the Windy City because I’d cases that convert LED-lit façades of a thousand different faces, and discovered the Adventure Cycling Association’s into cycle trailers. on towards the Buckingham Fountain, the official maps for Bicycle Route 66. Route 66! A memory had With everything else starting point of the Bicycle Route 66. surfaced of Chuck Berry’s Juke Box Hits: “It winds stuffed into a 90L from Chicago to LA, More than two thousand miles soft backpack, we ABRAHAM LINCOLN’S TOILET all the way”. -

America's Darling: Route 66 by Nathan Ward

WARD ROUTE 66 - 1 America’s Darling Story and photos by Nathan Ward WARD ROUTE 66 - 1 t is Friday night, and with the your wheels like a road map to the last gasp of the day, a golden promised land. glow burns low across Central The fabled Route 66 still holds Avenue in Albuquerque, New the lure of discovery, and Americans IMexico. It throws a storied slant on love that promise of potential. Back the time-pitted windows of a blue in 1926. Right now. Tomorrow. I 1968 Ford Mustang, cruising slowly can’t define it, but there is certainly in front of the bright lights of the something about the idea of Route Route 66 KiMo Theater. Lost in the sound of 66 that promises happiness. There glass-pack mufflers burbling out a is no better way to discover The V8 song, we glide on bicycles east Mother Road’s mysteries than to on the avenue to the pink and teal ponder them slowly at bicycling neon of the Route 66 Diner where speed. the promise of the past lives on. From Chicago, Route 66 starts On Friday nights in Albuquerque, down Jackson Boulevard, crosses it’s not the best hour for bicycles, Illinois and Missouri, tastes Kansas, but we persist just as the legend of and digs deep into Oklahoma, the Route 66 persists in the dreams of Texas Panhandle, New Mexico, people worldwide. Arizona, and California — Lake Pull open the door. Inside the Michigan to the Pacific Ocean. Route 66 Diner, the needle drops It’s a classic journey best done on a 45 and “Tucumcari, Here I in one push, but we decided to Come” by Dale Watson bursts out. -

New Mexico Prioritized Statewide Bicycle Network Plan

New Mexico Prioritized Statewide Bicycle Network Plan DECEMBER 2018 New Mexico Prioritized Statewide Bicycle Network Plan December 2018 NM Bike Plan Acknowledgements We would like to acknowledge the help of the following New Mexico Department of Transportation staff in helping to create this plan, as well as the organizations that supported the development of the plan through participation in coordinating meetings, public meetings, and feedback. NMDOT would like to thank the engaged residents of New Mexico and beyond who provided valuable public comment and input throughout the planning process. New Mexico Department of Transportation Secretary Tom Church Jonathan Fernandez Deputy Secretary Anthony Lujan Judith Gallardo Aaron Chavarria Ken Murphy Adam Romero Kimberly Gallegos Afshin Jian Larry Maynard Ami Evans Lawrence Lopez Antonio Jaramillo Leo Montoya Arif Kazmi Manon Arnett Armando Armendariz Margaret Haynes Bill Craven Nancy Perea Bill Hutchinson Paul Brasher David Trujillo Rhonda Lopez Delane Baros Richard Pena Emilee Cantrell Richard Ramoso Francisco Sanchez Rick Padilla Franklin Garcia Rosa Kozub Gabe Lucero Rosanne Rodriguez Gabriela Contreras-Apodaca Shannon Glendenning Harold Love Stephanie Parra Heather Sandoval Stephen Lopez Jennifer Mullins Tamara Haas Jessica Crane Tim Parker Jessica Griffin Trent Doolittle Jill Mosher Wade Patterson Jolene Herrera Yvonne Aragon Participating Organizations City of Santa Fe Bicycle Trails Advisory Committee El Paso MPO Members and Staff Farmington MPO Members and Staff FHWA-New Mexico Division -

New Mexico Bicyclist

THE BICYCLE COALITION OF NEW MEXICO SPRING 2011 New Mexico Bicyclist 2011 New Mexico Bicycle Almanac VOL 5, NO 1 A NOTE FROM THE EDITOR BCNM COMMITTEES Inside Back in the early 1980’s, the League In March 2010, in order to provide of American Wheelmen (LAW, now the members with an opportunity to serve in 2: NM Bicycle League of American Bicyclists) came out an area of personal interest, the Bicycle Routes with a comprehensive Almanac on Coalition of New Mexico (BCNM) 3: Places to Ride Bicycling in America. The publication Board of Directors instituted a 4: NM Bicycle contained all kinds of useful information committee structure comprising the six Laws on almost everything related to riding, E’s in alignment with the League of 4: Useful Websites and I always looked forward to getting it American Bicyclists’ equity statement. 5: Event Calendar in the mail at the start of each riding Education season. The League continued 6: Organizations Wes Young - Chair. Cycling publishing the Almanac for many years 9: NM Bicycle training should be based on the principle but it got smaller and smaller and after Businesses that “cyclists fare best when they act and 2008 they stopped printing it after are treated as drivers of vehicles.” This moving the information to the web. type of cycling is based on the same As Editor of New Mexico Bicyclist, I BCNM Board sound, proven traffic principles thought that there was a need for a governing all drivers, and is the safest, bicycle almanac covering our State. I President: most efficient way for all cyclists to decided to make the Spring issue of New Diane Albert operate. -

New Mexico Bicyclist

THE BICYCLE COALITION OF NEW MEXICO SPRING 2011 New Mexico Bicyclist 2011 New Mexico Bicycle Almanac VOL 5, NO 1 A NOTE FROM THE EDITOR BCNM COMMITTEES Inside Back in the early 1980’s, the League In March 2010, in order to provide of American Wheelmen (LAW, now the members with an opportunity to serve in 2: NM Bicycle League of American Bicyclists) came out an area of personal interest, the Bicycle Routes with a comprehensive Almanac on Coalition of New Mexico (BCNM) 3: Places to Ride Bicycling in America. The publication Board of Directors instituted a 4: NM Bicycle contained all kinds of useful information committee structure comprising the six Laws on almost everything related to riding, E’s in alignment with the League of 4: Useful Websites and I always looked forward to getting it American Bicyclists’ equity statement. 5: Event Calendar in the mail at the start of each riding Education season. The League continued 6: Organizations Wes Young - Chair. Cycling publishing the Almanac for many years 9: NM Bicycle training should be based on the principle but it got smaller and smaller and after Businesses that “cyclists fare best when they act and 2008 they stopped printing it after are treated as drivers of vehicles.” This moving the information to the web. type of cycling is based on the same As Editor of New Mexico Bicyclist, I BCNM Board sound, proven traffic principles thought that there was a need for a governing all drivers, and is the safest, bicycle almanac covering our State. I President: most efficient way for all cyclists to decided to make the Spring issue of New Diane Albert operate. -

2021 New Mexico Bicycle Guide

2021 New Mexico Bicycle Guide INSIDE NM Bike Plan NM Bike Maps ACA Bicycle Routes NM Bicycle Laws US Bicycle Route System Bicycle Events Useful Websites Organizations NM Businesses Published by the New Mexico Bike Summit - A Nonprofit Corporation From the Editor Albuquerque City Bike Map http://www.cabq.gov/parksandrecreation/recreation/bike/ This is the third New Mexico Guide I have published. bike-map The first was the Spring 2011 issue of New Mexico Bicyclist put out by the Bicycle Coalition of New Farmington city bike map Mexico. Last year, I revived the guide for the New http://www.fmtn.org/DocumentCenter/View/748/ Mexico Bike Summit. I have tried to get the most city_bike_map?bidId= accurate information I could, but if there is something important out, let me know at [email protected] Las Cruces City Bike Map (4.5 mb PDF, two sided) and I will get in next guide. http://mesillavalleympo.org/wp-content/uploads/ - Chris Marsh, Editor 2016/01/061115bikesuitabilityfinaldraft.pdf About the New Mexico Bike Rio Rancho City Bike Map (north side): https://www.rrnm.gov/DocumentCenter/ Summit View/63553/bikemap-north?bidId= The New Mexico Bike Summit is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit (south side): https://www.rrnm.gov/DocumentCenter/ corporation that promotes, develops, encourages, and View/63554/bikemap-south?bidId= supports bicycle education, safety, and advocacy to Santa Fe City Bike Map (7.36 mb PDF) youth and adults in New Mexico primarily by holding the New Mexico Bike Summit and related activities. http://santafempo.org/wp-content/uploads/2009/07/ Look for future Bike Summit meetings via Zoom! Front_Bikeways_and_Trails_map_2015.pdf 2021 Bike Summit Board of Directors New Mexico Adventure Cycling President: Tammy Schurr Routes Vice President: Christopher Marsh Secretary: George Pearson The Adventure Cycling Association has been mapping Treasurer and Webmaster: Jeff Saul out cross country routes in the US since 1973. -

2020 New Mexico Bicycle Guide

INSIDE New Mexico NM Bike Plan Bicycle Guide NM Bike Maps ACA Bicycle Routes NM Bicycle Laws US Bicycle Route System Bicycle Events Useful Websites Organizations NM Businesses Published by the New Mexico Bike Summit - A Nonprofit Corporation From the Editor New Mexico Bicycle Maps Back in the early 1980’s, the League of American Wheelmen (LAW, now the League of American Below are links to state and local bike maps. Bicyclists) came out with a comprehensive Almanac on State Bicycle Guideline Map Bicycling in America. The publication contained all Interactive online map: https://nmdot.maps.arcgis.com/ kinds of useful information on almost everything related apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=25379a5f300c4aafbd to riding, and I always looked forward to getting it in the 36147c7c7127d1 mail at the start of each riding season. The League continued publishing the Almanac for many years but it Two-sided PDF, 12.4 mb:https://dot.state.nm.us/ got smaller and smaller and after 2008 they stopped content/dam/nmdot/BPE/NMBikeGuidelineMap.pdf printing it after moving the information to the web. Albuquerque City Bike Map As Vice President of the New Mexico BikeSummit, I http://www.cabq.gov/parksandrecreation/recreation/bike/ thought that there was a need for a bicycle guide bike-map covering our State. I decided to put together this guide. I tried to get the most accurate information I could, but if Farmington city bike map there is something important out, let me know at http://www.fmtn.org/DocumentCenter/View/748/ [email protected] and I will get in next guide.