Analysis of Sauger Spawning Success in Watts Bar Tailwater, 2001, During April Minimum Flows of 6,000 Cfs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume II Watts Bar Land Plan Amendment

WATTS BAR RESERVOIR LAND MANAGEMENT PLAN AMENDMENT VOLUME II July 2021 This page intentionally left blank Document Type: EA Administrative Record Index Field: Final EA Project Name: Watts Bar RLMP Amendment Project Number: 2017-5 WATTS BAR RESERVOIR Loudon, Meigs, Rhea, and Roane Counties, Tennessee Land Management Plan Amendment VOLUME II Prepared by Tennessee Valley Authority July 2021 This page intentionally left blank Contents Table of Contents APPENDICES ............................................................................................................................II LIST OF TABLES .......................................................................................................................II LIST OF FIGURES .....................................................................................................................II ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................................... III CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Tennessee Valley Authority History .............................................................................. 2 1.2 Overview of TVA’s Mission and Environmental Policy ................................................... 3 1.2.1 TVA’s Mission ....................................................................................................... 3 1.2.2 Environmental Policy ........................................................................................... -

Watershed Water Quality Management Plan

LOWER TENNESSEE RIVER WATERSHED-GROUP 4 (06020001) OF THE TENNESSEE RIVER BASIN WATERSHED WATER QUALITY MANAGEMENT PLAN TENNESSEE DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND CONSERVATION DIVISION OF WATER POLLUTION CONTROL WATERSHED MANAGEMENT SECTION Presented to the people of the Lower Tennessee River Watershed by the Division of Water Pollution Control October 9, 2007. Prepared by the Chattanooga Environmental Field Office: Mark A. Barb Scott A. Howell Darryl Sparks Richard D. Urban And the Nashville Central Office, Watershed Management Section: Richard Cochran David Duhl Regan McGahen Josh Upham Jennifer Watson Sherry Wang, Manager LOWER TENNESSEE RIVER WATERSHED (GROUP 4) WATER QUALITY MANAGEMENT PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS Glossary Summary Chapter 1. Watershed Approach to Water Quality Chapter 2. Description of the Lower Tennessee River Watershed Chapter 3. Water Quality Assessment of the Lower Tennessee River Watershed Chapter 4. Point and Nonpoint Source Characterization of the Lower Tennessee River Watershed Chapter 5. Water Quality Partnerships in the Lower Tennessee River Watershed Chapter 6. Restoration Strategies Appendix I Appendix II Appendix III Appendix IV Appendix V Glossary GLOSSARY 1Q20. The lowest average 1 consecutive days flow with average recurrence frequency of once every 20 years. 30Q2. The lowest average 3 consecutive days flow with average recurrence frequency of once every 2 years. 7Q10. The lowest average 7 consecutive days flow with average recurrence frequency of once every 10 years. 303(d). The section of the federal Clean Water Act that requires a listing by states, territories, and authorized tribes of impaired waters, which do not meet the water quality standards that states, territories, and authorized tribes have set for them, even after point sources of pollution have installed the minimum required levels of pollution control technology. -

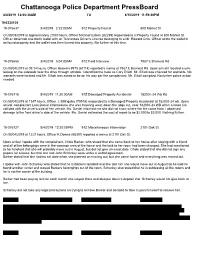

Week of 08-04-19 Through 08-10-19 Redacted

8/4/2019 12:00:36AM TO 8/10/2019 11:59:36PM TN0330100 19-076637 8/4/2019 2:22:00AM 91Z Property Found 800 Market St On 08/03/2019 at approximately 20:00 hours, Officer Michael Estock (82259) responded to a Property Found at 800 Market St. Officer observed one black wallet with an Tennessee Driver's License belonging to a Mr. Edward Crim. Officer wrote the wallet in as found property and the wallet was then turned into property. No further at this time. 19-076655 8/4/2019 5:04:00AM 91Z Field Interview 7987 E Brainerd Rd On 08/04/2019 at 05:14 hours, Officer Beavers #975 (61114) reported a memo at 7987 E Brainerd Rd. Upon arrival I located a w/m asleep on the sidewalk near the drive through window. I identified the male as Cory Elliott. Mr. Elliott was checked for warrants. No warrants were located and Mr. Elliott was asked to be on his way per the complainant. Mr. Elliott complied. No further police action needed. 19-076716 8/4/2019 11:30:00AM 91Z Damaged Property Accidental 18200 I-24 Wb Rd On 08/04/2019 at 11:47 hours, Officer J. Billingsley (79518) responded to a Damaged Property Accidental at 18200 I-24 wb. Upon arrival, complainant Lora Daniel informed me she was traveling west, down the ridge cut, near 18200 I-24 WB when a loose tire collided with the driver's side of her vehicle. Ms. Daniel informed me she did not know where the tire came from. -

Chickamauga Land Management Plan

CHICKAMAUGA RESERVOIR FINAL RESERVOIR LAND MANAGEMENT PLAN Volume II MULTIPLE RESERVOIR LAND MANAGEMENT PLANS FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT August 2017 This page intentionally left blank Document Type: EIS Administrative Record Index Field: Final EIS Project Name: Multiple RLMPs & CVLP EIS Project Number: 2016-2 CHICKAMAUGA RESERVOIR Final Reservoir Land Management Plan VOLUME II MULTIPLE RESERVOIR LAND MANAGEMENT PLANS FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Prepared by Tennessee Valley Authority August 2017 This page intentionally left blank Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ...................................................................................................... II-V CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. II-1 1.1 Tennessee Valley Authority History ............................................................................. II-2 1.2 Overview of TVA’s Mission and Environmental Policy ................................................ II-2 TVA’s Mission ....................................................................................................... II-2 Environmental Policy ............................................................................................ II-3 Land Policy ........................................................................................................... II-3 Shoreline Management Policy ............................................................................. -

Rg~ Tow Near Kingston 705 649

bK~'~ ~HUIO '~U~A A~ U~ U7/Z1/j8 PAGe 3 PROJECT NAM~: WATT~ BAR (HYDRO) PROJECT NUMBER: 9 PHOTOGUPH SHEET PHOTOGRAPH FORMAT DATE NUMBER _ ~UflBEL___ nIL; __ __ _ __ __ __ _ __ _ __ CODE AV 981 WATTS BAR DAM 705 941 A.V 982 ____ WATTS BAR OAf! _ _ _ _ _ _ 705 941 AV 983 WATTS BAR DAM 705 941 .. Iy 964 WATTS SAR nOM 705 94' AV 985 WATTS BAR DAM 705 941 q av 986 WATTS eAR DAM 705 94' .. AV1016 WATTS BAR 705 142 .. AVl017 WATTS au 70S 142 AV1018 WATTS BAR 705 14Z .. 01019 WATTS BAR 705 142 If AV1020 WATTS BAR 70S 142 •• !Vl0ll WATTS BAR 105 142 AV1022 WATTS BAR 705 142 • . n1QZ3 WATIS BAR 705 142 IV1024 WATTS BAR 705 142 AV1025 _____ w..LTT.s_llR 705 U., • AV1167 WATTS BAR HYDRO 705 643 • Aylles WATTS BAR HYDRO 705 643 • AV1169 WATTS BA~ HYORO 705 643 • AVllZa WATTS eAR HYDRO 705 643 • AV1171 WATTS BAR HYDRO 705 643 • AVll72 _ __ llA.IiLBU DAM AND STEAM Pi ANT 705 643 • AV1173 WATTS BAR OAM AND STEAM PLANT 705 643 • AV1174 WATTS BAR DAM 705 643 • AV1539 6 WATTS !UR LOCK & DAM 705 649 • Ay1539 1 . WATTS BAR LOCK , DAM 705 649 • AV1539 8 WATTS ~AR LOCK ~ DAM 70S 6~9 • AY1519 , WATTS ,4R I PC! , nOM 705 649 • AV1539 11 WATTS BAR LOCK & DAM 705 649 AV1539 __1L _ nus au LOCK t DAM 705 649 .. AV1546 1 SPRING CITY, TENN. WATERFRONT 705 649 • AV1546 2 SPRING CITY, UriNe WATeRFRONT 705 649 • AV1546 1 SPRING CITY, TENN. -

Paddler's Guide to Civil War Sites on the Water

Southeast Tennessee Paddler’s Guide to Civil War Sites on the Water If Rivers Could Speak... Chattanooga: Gateway to the Deep South nion and Confederate troops moved into Southeast Tennessee and North Georgia in the fall of 1863 after the Uinconclusive Battle of Stones River in Murfreesboro, Tenn. Both armies sought to capture Chattanooga, a city known as “The Gateway to the Deep South” due to its location along the he Tennessee River – one of North America’s great rivers – Tennessee River and its railroad access. President Abraham winds for miles through Southeast Tennessee, its volume Lincoln compared the importance of a Union victory in Tfortified by gushing creeks that tumble down the mountains Chattanooga to Richmond, Virginia - the capital of the into the Tennessee Valley. Throughout time, this river has Confederacy - because of its strategic location on the banks of witnessed humanity at its best and worst. the river. The name “Tennessee” comes from the Native American word There was a serious drought taking place in Southeast Tennessee “Tanasi,” and native people paddled the Tennessee River and in 1863, so water was a precious resource for soldiers. As troops its tributaries in dugout canoes for thousands of years. They strategized and moved through the region, the Tennessee River fished, bathed, drank and traveled these waters, which held and its tributaries served critical roles as both protective barriers dangers like whirlpools, rapids and eddies. Later, the river was and transportation routes for attacks. a thrilling danger for early settlers who launched out for a fresh The two most notorious battles that took place in the region start in flatboats. -

Hamilton County E911 Active Calls

Hamilton County E911 Active Calls entry_id created agency 58FD-2015-Apr-0002 04/01/2015 11:31:00 AM Highway 58 Volunteer Fire Department 58FD-2015-Apr-0011 04/02/2015 05:11:00 PM Highway 58 Volunteer Fire Department 58FD-2015-Apr-0013 04/03/2015 07:32:00 AM Highway 58 Volunteer Fire Department 58FD-2015-Apr-0015 04/03/2015 08:23:00 AM Highway 58 Volunteer Fire Department 58FD-2015-Apr-0020 04/03/2015 09:51:00 PM Highway 58 Volunteer Fire Department 58FD-2015-Apr-0024 04/04/2015 08:09:00 PM Highway 58 Volunteer Fire Department 58FD-2015-Apr-0027 04/05/2015 01:41:00 AM Highway 58 Volunteer Fire Department 58FD-2015-Apr-0033 04/05/2015 01:31:00 PM Highway 58 Volunteer Fire Department 58FD-2015-Apr-0036 04/05/2015 06:28:00 PM Highway 58 Volunteer Fire Department 58FD-2015-Apr-0037 04/06/2015 01:59:00 AM Highway 58 Volunteer Fire Department Page 1 of 2135 09/25/2021 Hamilton County E911 Active Calls incident_type FROAD ROAD VEHICLE ON FIRE (CAR/TRUCK FIRE) FASCIT-FIRE DEPARTMENT ASSISTING A CITIZEN FASCIT-FIRE DEPARTMENT ASSISTING A CITIZEN AFA RESIDENTIAL AFA RESIDENTIAL CHIMNEY-CHIMNEY FIRE FASCIT-FIRE DEPARTMENT ASSISTING A CITIZEN FASCIT-FIRE DEPARTMENT ASSISTING A CITIZEN FMUAID-FIRE DEPARTMENT MUTUAL AID ALARM AFA RESIDENTIAL Page 2 of 2135 09/25/2021 Hamilton County E911 Active Calls address 8651 BRENDA CT, HAMILTON COUNTY (BRENDA DR/DEAD END) #[8600-8699] 7506 DAVIS MILL RD, HAMILTON COUNTY (PAMELA DR/STICHER TRL) #[7430-7523] [7430-7523] [0-0] @NAPFE TOWER (5465 HIGHWAY 58, HAMILTON COUNTY) 7001 SENTINEL LN, HAMILTON COUNTY (STONEWALL -

Guntersville Reservoir

GUNTERSVILLE RESERVOIR Final Environmental Impact Statement and Reservoir Land Management Plan Volume I SEPTEMBER 2001 This page intentionally left blank Document Type: EA-Administrative Record Index Field: White Paper Project Name: Deeded Land Use Rights Project Number: 2009-57 ENVIRONMENTAL REPORT RECOGNITION OF DEEDED ACCESS RIGHTS IN THREE TENNESSEE VALLEY AUTHORITY RESERVOIR LAND MANAGEMENT PLANS Guntersville Reservoir, Alabama; Norris Reservoir, Tennessee; and Pickwick Reservoir, Alabama PREPARED BY: TENNESSEE VALLEY AUTHORITY MARCH 2010 Prepared by: Richard L. Toennisson NEPA Compliance Tennessee Valley Authority 400 West Summit Hill Drive Knoxville, Tennessee 37902 Phone: 865-632-8517 Fax: 865-632-3451 E-mail: [email protected] Page intentionally blank ENVIRONMENTAL REPORT RECOGNITION OF DEEDED ACCESS RIGHTS IN THREE TENNESSEE VALLEY AUTHORITY RESERVOIR LAND MANANAGEMENT PLANS GUNTERSVILLE RESERVOIR, ALABAMA; NORRIS RESERVOIR, TENNESSEE; AND PICKWICK RESERVOIR, ALABAMA TENNESSEE VALLEY AUTHORITY MARCH 2010 Issue The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) uses a land planning process to allocate individual parcels on its reservoir lands to one of six land use zones. After approval of a reservoir land management plan (LMP) by the TVA Board of Directors (TVA Board), all future uses of TVA lands on that reservoir must then be consistent with the allocations within that LMP. TVA’s Land Policy (TVA 2006) states that TVA may consider changing a land use designation outside of the normal planning process only for the purposes of providing water access for industrial or commercial recreation operations on privately owned back-lying land or to implement TVA’s Shoreline Management Policy (SMP). A change in allocation of any parcel is subject to approval by the TVA Board or its designee. -

Water-Quality Appraisal of N Asqan Stations Below Impoundments, Eastern Tennessee

WATER-QUALITY APPRAISAL OF N ASQAN STATIONS BELOW IMPOUNDMENTS, EASTERN TENNESSEE R.D. Evaldi and J.G. Lewis U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 85-4171 Knoxville, Tennessee 1986 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DONALD PAUL HODEL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director For additional information Copies of this report can be write to: purchased from: District Chief Open-File Services Section U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey A-413 Federal Bldg. Box 25425, Federal Center Nashville, TN 37203 Lakewood, CO 80225 CONTENTS Abstract 1 Introduction 1 Objective 2 Basin description 2 Location 2 Topography 2 Climate 2 Population 5 Geology 5 Soils 6 Land use 6 Surface drainage 9 Hydrologic modifications 1 1 Quality of water data 14 Data sources 14 NASQANdata 14 Trend analysis techniques 18 Water-quality summaries and trend test results 19 Water type 25 Common constituents 25 Dissolved solids 25 Specific conductance 25 Hydrogen-ion activity (pH) 40 Sulf ate 41 Trace constituents 41 Mercury 41 Iron 42 Nutrients 42 Nitrogen 42 Phosphorus 42 Organics and biological 43 Fecal coliform bacteria 43 Organic carbon 4 3 Sediment 43 Suspended sediment 44 Bed material 44 Water temperature 45 Load computations 45 Reservoir stratification 47 Analysis of trend procedures 48 Summary and conclusions 48 References cited 4 9 111 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1-4. Maps showing: 1. Location of the study area and relation to physiographic provinces 2. Generalized geology and cross section of the NASQAN accounting unit above Watts Bar Dam 4 3. Generalized soils of the NASQAN accounting unit above Watts Bar Dam 7 4. -

Waterway Management Plan 2020 TENNESSEE RIVER Waterway Management Plan

TENNESSEE RIVER Waterway Management Plan 2020 TENNESSEE RIVER Waterway Management Plan A JOINT PROJECT OF THE TENNESSEE RIVER VALLEY ASSOCIATION, TENNESSEE-CUMBERLAND WATERWAY COUNCIL, U.S. ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS, U.S. COAST GUARD AND TENNESSEE VALLEY AUTHORITY This document contains time-dependent material and is current through January 2020 Revision Record June 1999 – Original issue. June 2000 – Section 2.1.1, added paragraph; Appendix I, deleted Charleston Marine Transport; revised note to Kentucky tailwater; miscellaneous editorial changes. September 2003 – Section 7.1.1, edited paragraph; Appendix I, revised contacts, Appendix II, changed several phase criteria. July 2014 – Appendix A, revised agency contacts; revised Appendix B, Phase Criteria; revised appendices labeling; miscellaneous editorial changes. January 2020 – Appendix A, revised agency contacts; revised Appendix C; miscellaneous editorial changes. Contents Forward ...................................................................................... 2 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................... 3 2.0 Hydrology and Meteorology.................................................................. 4 2.1 Purpose . 4 2.1.1 Hydrological and Meteorological Factors Affecting Waterway Management ..................... 4 3.0 Waterway Management ..................................................................... 6 3.1 Goal .................................................................................. 6 3.2 Marine Transportation -

Invasive Aquatic Plants Impacts on Watts Bar Lake and the Tennessee River Ecosystem & Control Recommendations

1 Invasive Aquatic Plants Impacts on Watts Bar Lake and the Tennessee River Ecosystem & Control Recommendations by Watts Bar Ecology and Fishery Council (WBEFC) (Dr. Timothy Joseph, Chairman) Report to the Roane County Commission-- Aquatic Weeds Committee EXECUTIVE SUMMARY It is well known locally that nonnative invasive aquatic plants have infested Watts Bar Lake and the Tennessee River ecosystem. This is a significant issue for nearly every state in the U.S. The Watts Bar Ecology and Fishery Council (WBEFC) was created at the request of the Aquatic Weeds Committee of the Roane County Commission to provide advice on the impacts and control measures. This report is the result of extensive research, compilation, and assessment efforts, and is based on factual evidence and decades of published research on more than 300 lakes. This report describes the invasive aquatic species of concern in Watts Bar Lake (e.g., Hydrilla, Eurasian Milfoil, and Spiny Leaf Naiad), the lake’s current aquatic ecosystem (eutrophic/aging with built up concentration of nutrients including; carbon, phosphorus, and nitrogen), and impacts on fish species and fish population growth. The discussion of the lake’s aquatic ecosystem includes the topics of ecosystem dynamics, littoral zone dynamics, fish reproduction, and ecological impacts of invasive aquatic plants. Research showed that while some amount of aquatic plants is beneficial to the ecosystem (< 40% coverage), invasive plants quickly overtake the littoral zone (>40% coverage). The ecosystem then becomes uninhabitable by fish, water circulation is prevented, dissolved oxygen is severely depleted, water temperature increases greatly, and fish food organisms are killed. Fish populations ultimately undergo a major decline in number and diversity. -

Tennessee River Blueway Information

About the Tennessee River Blueway Formed by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) in the 1930’s, and designated as a river trail in 2002, the Tennessee River Blueway flows through Chattanooga and the Tennessee River Gorge for 50 miles, from Chickamauga Dam to Nickajack Dam. It provides opportunities for canoeists and kayakers to take day trips, or camp overnight in marinas, parks, or in one of five designated primitive sites. Just a few miles downstream from Chickamauga Dam, downtown Chattanooga offers accessible riverfront amenities on both shores. Paddlers can visit public parks and plazas, restaurants and coffee shops, galleries and museums, and attractions. Natural and man made features to be seen from the water include the restored 19th century Walnut Street Pedestrian Bridge, the Chief John Ross (Market Street) Bridge, Maclellan Island, the Museum Bluffs, and the Passage at Ross’ Landing. From Chattanooga, the Blueway winds around the Moccasin Bend National Archaeological District and historic Williams Island, then past Suck Creek to the Tennessee River Gorge Trust’s Pot Point House. The 1835 hand- hewed log cabin was restored in 1993. It was originally built with recycled logs taken from a flat boat that wrecked at the "The Boiling Pot,” formerly the most treacherous rapids in the Gorge. Nearby are Prentice Cooper State Forest and the TVA Raccoon Mountain Pump Storage Facility, which holds water for hydro-electric power generation. Atop the mountain is a man-made reservoir created by an impressive 230-foot-high, 8,500 foot-long dam. A visitors center, picnic facilities, and a network of trails around the reservoir offer recreation for hikers and mountain bikers.