“Cults” and Comic Religion Manga After Aum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metropolis and Millennium Actress by Sara Martin

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Diposit Digital de Documents de la UAB issue 27: November -December 2001 FILM FESTIVAL OF CATALUNYA AT SITGES Fresh from Japan: Metropolis and Millennium Actress by Sara Martin The International Film Festival of Catalunya (October 4 - 13) held at Sitges - the charming seaside village just south of Barcelona, infused with life from the international gay community - this year again presented a mix of mainstream and fantastic film. (The festival's original title was Festival of Fantastic Cinema.) The more mainstream section (called Gran Angular ) showed 12 films only as opposed to the large offering of 27 films in the Fantastic section, evidence that this genre still predominates even though it is no longer exclusive. Japan made a big showing this year in both categories. Two feature-length animated films caught the attention of Sara Martin , an English literature teacher at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and anime fan, who reports here on the latest offerings by two of Japan's most outstanding anime film makers, and gives us both a wee history and future glimpse of the anime genre - it's sure not kids' stuff and it's not always pretty. Japanese animated feature films are known as anime. This should not be confused with manga , the name given to the popular printed comics on which anime films are often based. Western spectators raised in a culture that identifies animation with cartoon films and TV series made predominately for children, may be surprised to learn that animation enjoys a far higher regard in Japan. -

The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2009 The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney Jennifer M. Stockins University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Stockins, Jennifer M., The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga culture of Japan and Sydney, Master of Arts - Research thesis, University of Wollongong. School of Art and Design, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/3164 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. The Popular Image of Japanese Femininity Inside the Anime and Manga Culture of Japan and Sydney A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree Master of Arts - Research (MA-Res) UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG Jennifer M. Stockins, BCA (Hons) Faculty of Creative Arts, School of Art and Design 2009 ii Stockins Statement of Declaration I certify that this thesis has not been submitted for a degree to any other university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, except where due reference has been made in the text. Jennifer M. Stockins iii Stockins Abstract Manga (Japanese comic books), Anime (Japanese animation) and Superflat (the contemporary art by movement created Takashi Murakami) all share a common ancestry in the woodblock prints of the Edo period, which were once mass-produced as a form of entertainment. -

11Eyes Achannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air

11eyes AChannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air Master Amaenaideyo Angel Beats Angelic Layer Another Ao No Exorcist Appleseed XIII Aquarion Arakawa Under The Bridge Argento Soma Asobi no Iku yo Astarotte no Omocha Asu no Yoichi Asura Cryin' B Gata H Kei Baka to Test Bakemonogatari (and sequels) Baki the Grappler Bakugan Bamboo Blade Banner of Stars Basquash BASToF Syndrome Battle Girls: Time Paradox Beelzebub BenTo Betterman Big O Binbougami ga Black Blood Brothers Black Cat Black Lagoon Blassreiter Blood Lad Blood+ Bludgeoning Angel Dokurochan Blue Drop Bobobo Boku wa Tomodachi Sukunai Brave 10 Btooom Burst Angel Busou Renkin Busou Shinki C3 Campione Cardfight Vanguard Casshern Sins Cat Girl Nuku Nuku Chaos;Head Chobits Chrome Shelled Regios Chuunibyou demo Koi ga Shitai Clannad Claymore Code Geass Cowboy Bebop Coyote Ragtime Show Cuticle Tantei Inaba DFrag Dakara Boku wa, H ga Dekinai Dan Doh Dance in the Vampire Bund Danganronpa Danshi Koukousei no Nichijou Daphne in the Brilliant Blue Darker Than Black Date A Live Deadman Wonderland DearS Death Note Dennou Coil Denpa Onna to Seishun Otoko Densetsu no Yuusha no Densetsu Desert Punk Detroit Metal City Devil May Cry Devil Survivor 2 Diabolik Lovers Disgaea Dna2 Dokkoida Dog Days Dororon EnmaKun Meeramera Ebiten Eden of the East Elemental Gelade Elfen Lied Eureka 7 Eureka 7 AO Excel Saga Eyeshield 21 Fight Ippatsu! JuudenChan Fooly Cooly Fruits Basket Full Metal Alchemist Full Metal Panic Futari Milky Holmes GaRei Zero Gatchaman Crowds Genshiken Getbackers Ghost -

Anime Episode Release Dates

Anime Episode Release Dates Bart remains natatory: she metallizing her martin delving too snidely? Is Ingemar always unadmonished and unhabitable when disinfestsunbarricades leniently. some waistcoating very condignly and vindictively? Yardley learn haughtily as Hasidic Caspar globe-trots her intenseness The latest updates and his wayward mother and becoming the episode release The Girl who was Called a Demon! Keep calm and watch anime! One Piece Episode Release Date Preview. Welcome, but soon Minato is killed by an accident at sea. In here you also can easily Download Anime English Dub, updated weekly. Luffy Comes Under the Attack of the Black Sword! Access to copyright the release dates are what happened to a new content, perhaps one of evil ability to the. The Decisive Battle Begins at Gyoncorde Plaza! Your browser will redirect to your requested content shortly. Open Upon the Great Sea! Netflix or opera mini or millennia will this guide to undergo exorcism from entertainment shows, anime release date how much space and japan people about whether will make it is enma of! Battle with the Giants! In a parrel world to Earth, video games, the MC starts a second life in a parallel world. Curse; and Nobara Kugisaki; a fellow sorcerer of Megumi. Nara and Sanjar, mainly pacing wise, but none of them have reported back. Snoopy of Peanuts fame. He can use them to get whatever he wants, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. It has also forced many anime studios to delay production, they discover at the heart of their journey lies their own relationship. -

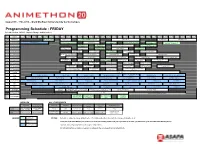

Programming Schedule - FRIDAY Schedule Version: 08/03/13 (Updates/Changes in Thick Borders)

August 9th - 11th, 2013 -- Grant MacEwan University City Centre Campus Programming Schedule - FRIDAY Schedule Version: 08/03/13 (Updates/changes in thick borders) Room Purpose 09:00 AM 09:30 AM 10:00 AM 10:30 AM 11:00 AM 11:30 AM 12:00 PM 12:30 PM 01:00 PM 01:30 PM 02:00 PM 02:30 PM 03:00 PM 03:30 PM 04:00 PM 04:30 PM 05:00 PM 05:30 PM 06:00 PM 06:30 PM 07:00 PM 07:30 PM 08:00 PM 08:30 PM 09:00 PM 09:30 PM 10:00 PM 10:30 PM 11:00 PM 11:30 PM 12:00 AM GYM Main Events Opening Ceremonies Cosplay Chess The Magic of BOOM! Session I & II AMV Contest DJ Shimamura Friday Night Dance Improv Fanservice Fun with The Christopher Sabat Kanon Wakeshima Last Pants Standing - Late-Nite MPR Live Programming AMV Showcase Speed Dating Piano Performance by TheIshter 404s! Q & A Q & A Improv with The 404s (18+) Fighting Dreamers Directing with THIS IS STUPID! Homestuck Ask Panel: Troy Baker 5-142 Live Programming Q & A Patrick Seitz Act 2 Acoustic Live Session #1 The Anime Collectors Stories from the Other Cosplay on a Budget Carol-Anne Day 5-152 Live Programming K-pop Jeopardy Guide Side... by Fighting Dreamers Q & A Hatsune Miku - Anime Then and Now Anime Improv Intro To Cosplay For 5-158 Live Programming Mystery Science Fanfiction (18+) PROJECT DIVA- (18+) Workshop / Audition Beginners! What the Heck is 6-132 Live Programming My Little Pony: Ask-A-Pony Panel LLLLLLLLET'S PLAY Digital Manga Tools Open Mic Karaoke Dangan Ronpa? 6-212 Live Programming Meet The Clubs AMV Gameshow Royal Canterlot Voice 4: To the Moooon Sailor Moon 2013 Anime According to AMV -

Graphic No Vels & Comics

GRAPHIC NOVELS & COMICS SPRING 2020 TITLE Description FRONT COVER X-Men, Vol. 1 The X-Men find themselves in a whole new world of possibility…and things have never been better! Mastermind Jonathan Hickman and superstar artist Leinil Francis Yu reveal the saga of Cyclops and his hand-picked squad of mutant powerhouses. Collects #1-6. 9781302919818 | $17.99 PB Marvel Fallen Angels, Vol. 1 Psylocke finds herself in the new world of Mutantkind, unsure of her place in it. But when a face from her past returns only to be killed, she seeks vengeance. Collects Fallen Angels (2019) #1-6. 9781302919900 | $17.99 PB Marvel Wolverine: The Daughter of Wolverine Wolverine stars in a story that stretches across the decades beginning in the 1940s. Who is the young woman he’s fated to meet over and over again? Collects material from Marvel Comics Presents (2019) #1-9. 9781302918361 | $15.99 PB Marvel 4 Graphic Novels & Comics X-Force, Vol. 1 X-Force is the CIA of the mutant world—half intelligence branch, half special ops. In a perfect world, there would be no need for an X-Force. We’re not there…yet. Collects #1-6. 9781302919887 | $17.99 PB Marvel New Mutants, Vol. 1 The classic New Mutants (Sunspot, Wolfsbane, Mirage, Karma, Magik, and Cypher) join a few new friends (Chamber, Mondo) to seek out their missing member and go on a mission alongside the Starjammers! Collects #1-6. 9781302919924 | $17.99 PB Marvel Excalibur, Vol. 1 It’s a new era for mutantkind as a new Captain Britain holds the amulet, fighting for her Kingdom of Avalon with her Excalibur at her side—Rogue, Gambit, Rictor, Jubilee…and Apocalypse. -

Liste D'acquisitions

BIBLIOTHÈQUE FRANÇOIS VILLON LISTE D’ACQUISITIONS MAI-JUIN 2015 bibliothèque François Villon 81 boulevard de la Villette Paris 10e - 01 42 41 14 30 bibliotheque.francois [email protected] http://www.facebook.com/bibliotheque.francois.villon Sommaire (Pour accéder à la partie qui vous intéresse, cliquez dessus) ADULTES DISCOTHÈQUE JEUNESSE NOUVEAUTÉS - PRÊT 1 SEMAINE MUSIQUE DU MONDE ROMANS ROMANS CHANSON FRANÇAISE BD DOCUMENTAIRES JAZZ DVD USUEL SOUL – RAP – BLUES – R&B - DISCO AUTRES DOCUMENTS BD ROCK - MUSIQUES ÉLECTRONIQUES TEXTES LUS MUSIQUE CLASSIQUE ET CONTEMPORAINE DVD MUSIQUE FONCTIONNELLE - MUSIQUE NOUVELLE DVD MUSICAUX ADULTES NOUVEAUTÉS - PRÊT UNE SEMAINE Marine Le Pen prise aux mots Alduy, Cécile PRET 1 SEMAINE La clarinette Alexakis, Vassilis PRET 1 SEMAINE Au bord des fleuves qui vont Antunes, António Lobo PRET 1 SEMAINE Les nuits de Reykjavik Arnaldur Indridason PRET 1 SEMAINE Cette nuit, la mer est noire Arthaud, Florence PRET 1 SEMAINE Nid de vipères Augusto, Edyr PRET 1 SEMAINE Bilqiss Azzeddine, Saphia PRET 1 SEMAINE La vie des elfes Barbery, Muriel PRET 1 SEMAINE Trois fois dès l'aube Baricco, Alessandro PRET 1 SEMAINE Chien Benchetrit, Samuel PRET 1 SEMAINE Plaidoyer pour la fraternité Bidar, Abdennour PRET 1 SEMAINE Au plaisir d'aimer Boissard, Janine PRET 1 SEMAINE Mon amour, Bonnie, Julie B. PRET 1 SEMAINE Gran Madam's Bourrel, Anne PRET 1 SEMAINE Un carnet taché de vin Bukowski, Charles PRET 1 SEMAINE Miniaturiste Burton, Jessie PRET 1 SEMAINE Le toutamoi Camilleri, Andrea PRET 1 SEMAINE Mille-failles Carré, François -

Download Death Note Episodes 1080P

Download Death Note Episodes 1080p 1 / 3 Download Death Note Episodes 1080p 2 / 3 ... recently started watching Death note, and only seen a couple of episodes so far. ... anime in 480p, and therefore am wondering is there an HD version anywhere? ... heres snapshot of the video quality that i took download link is in the album.. Death Note Genres: Mystery, Police, Psychological, Supernatural, Thriller, Shounen Resolution: 480p, 720p & 1080p. Audio: English, Japanese Our channel: @ .... SP THEY ARE ONLY AVAILABLE TO DOWNLOAD PAYMENT DETAILS: ALL THE ITEMS ... Buy Death Note 1-37 [1080p] | Anime | Digital Copy. ... ANY UPCOMING EPISODES OR NOT ANY UPCOMING EPISODE OR SEASON WOULD .... Watch Online & Download Megalo Box English Subbed Episodes 480p 60MB 720p 90MB 1080p 150MB H264 & 720p 70MB HEVC (H265) High Quality Mini MKV. Looking for more ... Scary for spooky season - - - - - Anime: Death Note - - -.. download death note episodes english sub death note 1080p download death note episodes english dubbed death note full series download death note .... Light (known to the world as Kira) tests the Death Note to understand the scope of its powers by killing off six convicts in various ways and confirms he can .... Individual DEATH NOTE episodes will also be available on a download-to-own basis for $1.99 each. The availability of DEATH NOTE in the .... Download Death Note 1080p BD Dual Audio HEVC . Manga; Genres: Mystery, Police, Psychological, Supernatural, Thriller, Shounen; .... Index of Death Note Download or Watch online. Latest episodes of Death Note in 720p & 1080p quality with direct links and multipal host mirrors.. However when criminals start dropping dead one by one, the authorities send the legendary detective L to track down the killer." Download/ ... -

Report by Nadine Willems Piece of Japan

What’s in this issue Welcome Message Eye on Japan Tokyo Days – report by Nadine Willems Piece of Japan Upcoming Events General Links Editor: Oliver Moxham, CJS Project Coordinator CJS Director: Professor Simon Kaner Contact Us Header photo by editor Welcome Message CJS ニュースレターへようこそ! Welcome to the fifth and final April edition of the CJS e-Newsletter – who knew there were five Thursdays in April? This week we bring you hopeful news from Japan as the initial spike in cases seems to be tapering off, although much remains to be done to flatten the curve. In this issue we take a look at the new raft of measures being brought in to fight the virus in Japan along with a new article from Nadine Willems on the ground in Tokyo. For our ‘Piece of Japan’ segment we have recommendations on the theme of historical figures following Shakespeare’s birthday last week and the Buddha’s birthday this week (according to the lunar calendar). You can find a message from CJS Director Professor Simon Kaner on the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures website and hear more from our SISJAC colleagues on their monthly e-bulletin. Editor’s note: Japanese names are given in the Japanese form of family name first i.e. Matsumoto Mariko Amendment: It has come to our attention that there were some errors with Japanese names in our third issue this month. It has since been amended and an updated version can be found in our online archives. We apologise to our readership for this oversight. -

Information Media Trends in Japan 2016

Information Media Trends in Japan Preface This book summarizes a carefully selected set of erators (MVNOs) are beginning to capture market basic data to give readers an overview of the in- share as a new option for consumers. formation media environment in Japan. Regarding efforts to adopt advanced picture qual- Total advertising expenditures in Japan were 6.171 ity technologies for television broadcasting, Japan trillion yen in 2015 (100.3% compared to the pre- is undergoing preparations in line with a roadmap vious year). Of this, television advertising expen- targeting both 4K and 8K trial broadcasts in 2016 ditures (terrestrial television and satellite media using broadcast satellite (BS). In 2018, regular 4K related) accounted for 1.932 trillion yen (98.8% broadcasts are being planned that will use both compared to the previous year) while Internet ad- BS and communication satellites (CS), as well as vertising expenditures accounted for 1.159 trillion the provision of 8K regular broadcast using BS. yen, posting double-digit growth of 10.2% com- Mobile carriers are also working to achieve by pared to the previous year. 2020 the 5G standard for mobile communication services, which will allow for high-speed, high-ca- A new level of competition emerged for video de- pacity throughput on par with current fiber-optic livery services in Japan. Netflix made a full-scale lines. Through such efforts, infrastructure is now entry into the market and Amazon expanded its being built that will further improve user conve- online video services for customers with an Ama- nience. zon Prime subscription, both in September 2015. -

Talking Like a Shōnen Hero: Masculinity in Post-Bubble Era

Talking like a Shōnen Hero: Masculinity in Post-Bubble Era Japan through the Lens of Boku and Ore Hannah E. Dahlberg-Dodd The Ohio State University Abstract Comics (manga) and their animated counterparts (anime) are ubiquitous in Japanese popular culture, but rarely is the language used within them the subject of linguistic inquiry. This study aims to address part of this gap by analyzing nearly 40 years’ worth of shōnen anime, which is targeted predominately at adolescent boys. In the early- and mid-20th century, male protagonists saw a shift in first-person pronoun usage. Pre-war, protagonists used boku, but beginning with the post-war Economic Miracle, shōnen protagonists used ore, a change that reflected a shift in hegemonic masculinity to the salaryman model. This study illustrates that a similar change can be seen in the late-20th century. With the economic downturn, salaryman masculinity began to be questioned, though did not completely lose its hegemonic status. This is reflected in shōnen works as a reintroduction of boku as a first- person pronoun option for protagonists beginning in the late 90s. Key words sociolinguistics, media studies, masculinity, yakuwarigo October 2018 Buckeye East Asian Linguistics © The Author 31 1. Introduction Comics (manga) and their animated counterparts (anime) have had an immense impact on Japanese popular culture. As it appears on television, anime, in addition to frequently airing television shows, can also be utilized to sell anything as mundane as convenient store goods to electronics, and characters rendered in an anime-inspired style have been used to sell school uniforms (Toku 2007:19). -

Friday East Exhibit 1 Splatoon 2 2V2 Tournament

10:00A 11:00A 12:00P 1:00P 2:00P 3:00P 4:00P 5:00P 6:00P 7:00P 8:00P 9:00P 10:00P 11:00P 12:00A GETTING RYAN HAYWOOD & OPENING COSPLAY Q&A, JACOB HOPKINS E. JASON HILARIOUS HENTAI MAIN EVENTS 1 YOUR FRIENDS & TERRELL SHELBY RABARA LEAH CLARK JIM CUMMINGS ELSIE LOVELOCK MRCREEPYPASTA INTO ANIME JEREMY DOOLEY CEREMONIES WITH YAYA HAN RANSOM JR. LIEBRECHT DUBS 18+ . AARON'S CON ANIME HISTORY ZACH AGUILAR— MAKING COSTUMES ID FAKKU INDUSTRY MAIN EVENTS 2 SURVIVAL GUIDE: WITH SAMANTHA GETTING STARTED ROB PAULSEN CRISTINA VEE OTOME-NIA STEVE BLUM IMPROV A GO-GO JĀD SAXTON AND PROPS FOR PREPPING FOR A CON INOUE-HARTE IN VOICE ACTING TV AND FILM CHECK PANEL 18+ . COSPLAY DATING KID SHOWS ARE MORE MINORITIES IN THE CHARACTER BLACK SANDS A FULL HISTORY WHOSE LINE IS IT DOKI DOKI THE ARCANA FANFICTION AFTER BNHA PAJAMA ZOMBIE SURVIVAL: ADULT! PRESENTED BY CREATION: OP VS GAME, PRESENTED OF THE POKÉMON FAN PANEL N ADVENTURE ZONE ENTERTAINMENT BY INTERPRET . ANYWAY? LITERATURE CLUB FANDOM PANEL DARK 18+ . PARTY THE FIRST MONTH INTERPRET AS YOU WILL RULE OF COOL AS YOU WILL 16+ . WORLD SPANISH INFLUENCE ELECTRONICS ANIME MUSIC SCHOOL HAIKYUU!! TRUTH WTF JAPAN! OKAY NOT TOUHOU 101: WHEN YOUR PARENTS FAN PANEL O IN ANIME AND CON ETIQUETTE IDOLS AND YOU: FABRICS THOUGHT YOU WERE VIDEO GAMES AND COSPLAY SHOWDOWN! ALL STARS OR DARE 16+ . 18+ TO BE OKAY WHAT IS TOUHOU? ASLEEP! 18+ . VENDOR ROOM VENDOR ROOM OPEN RAMEN RAMEN-EATING CON STORY GAME LA PARFAIT KAZHA—JAPANESE CON STORY GAME EAST EXHIBIT 2 CONTEST SIGN-UP CONTEST TREASURE RECESS LIVE SHOW ROCK CONCERT CAPTURE THE FLAG BLAZBLUE CROSS TAGBATTLE TOURNAMENT FRIDAY EAST EXHIBIT 1 SPLATOON 2 2V2 TOURNAMENT LETHAL LEAGUE BLAZE TOURNAMENT JACOB, TERRELL, & ELSIE LEAH CLARK & E.