Caldon-Thesis (4.092Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Friends, Enemies, and Fools: a Collection of Uyghur Proverbs by Michael Fiddler, Zhejiang Normal University

GIALens 2017 Volume 11, No. 3 Friends, enemies, and fools: A collection of Uyghur proverbs by Michael Fiddler, Zhejiang Normal University Erning körki saqal, sözning körki maqal. A beard is the beauty of a man; proverbs are the beauty of speech. Abstract: This article presents two groups of Uyghur proverbs on the topics of friendship and wisdom, to my knowledge only the second set of Uyghur proverbs published with English translation (after Mahmut & Smith-Finley 2016). It begins with a brief introduction of Uyghur language and culture, then a description of Uyghur proverb styles, then the two sets of proverbs, and finally a few concluding comments. Key words: Proverb, Uyghur, folly, wisdom, friend, enemy 1. Introduction Uyghur is spoken by about 10 million people, mostly in northwest China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. It is a Turkic language, most closely related to Uzbek and Salar, but also sharing similarity with its neighbors Kazakh and Kyrgyz. The lexicon is composed of about 50% old Turkic roots, 40% relatively old borrowings from Arabic and Persian, and 6% from Russian and 2% from Mandarin (Nadzhip 1971; since then, the Russian and Mandarin borrowings have presumably seen a slight increase due to increased language contact, especially with Mandarin). The grammar is generally head-final, with default SOV clause structure, A-N noun phrases, and postpositions. Stress is typically word-final. Its phoneme inventory includes eight vowels and 24 consonants. The phonology includes vowel harmony in both roots and suffixes, which is sensitive to rounded/unrounded (labial harmony) and front/back (palatal harmony), consonant harmony across suffixes, which is sensitive to voiced/unvoiced and front/back distinctions; and frequent devoicing of high vowels (see Comrie 1997 and Hahn 1991 for details). -

Genres, and Media. 1 As Wolfgang Mieder Has Observed, I

II 16. "Is SeeingBelieving?" (Haase) - DONALD P. HAASE IS SEEING BELIEVING? PROVERBS AND THE Fll..M ADAPTATION OF A F.AIRY TALE I For several decadesnow, a growing number of interdisciplinary studies have investigated the use of the proverb in diverse contexts, genres, and media.1 As Wolfgang Mieder has observed, paremiologists have begun to move beyond mere historical studies of the proverb in traditional societies and folk fonDS, and "have become aware of the use and function of traditional proverbs in modem technological and sophisticated societies" ("Proverb in the Modem Age" 118). As a consequence,paremiology has beenenriched not only by studiesd1at investigate proverbs in traditional folk genres, such as the folk and fairy tale, but by "important studies of proverbs in modem literature, in psychologicaltesting, and in the various forms of massmedia such as newspapers,magazines, and advertisements" ( 118). One of the media in our technological society that has not been given much attention by paremiologists, however, is fllm.1 Perhaps this neglect is due to the medium's essentially visual technology, in which pictures speaklouder than words, which are, on the other hand, the essenceof the proverb. But the primary verbal nature of the prov- erb has not obscured the fact that it often has an implicit image con- tent as well, nor has it kept paremiologists from investigating the proverb's use in paintings. emblems, and other visual media such as advertisements.Moreover ~ as long as films contain spoken words imitating the speechof life, it is likely that proverbs will be present in cinema too. In what follows. -

The Child and the Fairy Tale: the Psychological Perspective of Children’S Literature

International Journal of Languages, Literature and Linguistics, Vol. 2, No. 4, December 2016 The Child and the Fairy Tale: The Psychological Perspective of Children’s Literature Koutsompou Violetta-Eirini (Irene) given that their experience is more limited, since children fail Abstract—Once upon a time…Magic slippers, dwarfs, glass to understand some concepts because of their complexity. For coffins, witches who live in the woods, evil stepmothers and this reason, the expressions should be simpler, both in princesses with swan wings, popular stories we’ve all heard and language and format. The stories have an immediacy, much of we have all grown with, repeated time and time again. So, the the digressions are avoided and the relationship governing the main aim of this article is on the theoretical implications of fairy acting persons with the action is quite evident. The tales as well as the meaning and importance of fairy tales on the emotional development of the child. Fairy tales have immense relationships that govern the acting persons, whether these are psychological meaning for children of all ages. They talk to the acting or situational subjects or values are also more children, they guide and assist children in coming to grips with distinct. Children prefer the literal discourse more than adults, issues from real, everyday life. Here, there have been given while they are more receptive and prone to imaginary general information concerning the role and importance of fairy situations. Having found that there are distinctive features in tales in both pedagogical and psychological dimensions. books for children, Peter Hunt [2] concludes that textual Index Terms—Children, development, everyday issues, fairy features are unreliable. -

Analysis of Polarimetric Mini-SAR and Mini-RF Datasets for Surface Characterization and Crater Delineation on Moon †

Proceeding Paper Analysis of Polarimetric Mini-SAR and Mini-RF Datasets for Surface Characterization and Crater Delineation on Moon † Himanshu Kumari and Ashutosh Bhardwaj * Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing Department, Indian Institute of Remote Sensing, Dehradun 248001, India; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +91-9410319433 † Presented at the 3rd International Electronic Conference on Atmospheric Sciences, 16–30 November 2020; Available online: https://ecas2020.sciforum.net/. Abstract: The hybrid polarimetric architecture of Mini-SAR and Mini-RF onboard Indian Chan- drayaan-1 and LRO missions were the first to acquire shadowed polar images of the Lunar surface. This study aimed to characterize the surface properties of Lunar polar and non-polar regions con- taining Haworth, Nobile, Gioja, an unnamed crater, Arago, and Moltke craters and delineate the crater boundaries using a newly emerged approach. The Terrain Mapping Camera (TMC) data of Chandrayaan-1 was found useful for the detection and extraction of precise boundaries of the cra- ters using the ArcGIS Crater tool. The Stokes child parameters estimated from radar backscatter like the degree of polarization (m), the relative phase (δ), Poincare ellipticity (χ) along with the Circular Polarization Ratio (CPR), and decomposition techniques, were used to study the surface attributes of craters. The Eigenvectors and Eigenvalues used to measure entropy and mean alpha showed distinct types of scattering, thus its comparison with m-δ, m-χ gave a profound conclusion to the lunar surface. The dominance of surface scattering confirmed the roughness of rugged material. The results showed the CPR associated with the presence of water ice as well as a dihedral reflection inside the polar craters. -

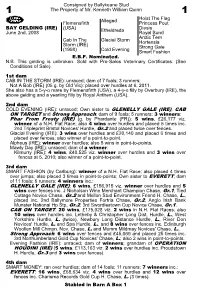

OPERATION HOUDINI (IRE) (5 Wins, £113,163 Viz

Consigned by Ballykeane Stud 1 The Property of Mr. Kenneth William Quinn 1 Hoist The Flag Alleged Flemensfirth Princess Pout BAY GELDING (IRE) (USA) Diesis June 2nd, 2008 Etheldreda Royal Bund Arctic Tern Cab In The Glacial Storm Hortensia Storm (IRE) Strong Gale (1998) Cold Evening Smart Fashion E.B.F. Nominated. N.B. This gelding is unbroken. Sold with Pre-Sales Veterinary Certificates. (See Conditions of Sale). 1st dam CAB IN THE STORM (IRE): unraced; dam of 7 foals; 3 runners: Not A Bob (IRE) (05 g. by Old Vic): placed over hurdles at 6, 2011. She also has a 5-y-o mare by Flemensfirth (USA), a 4-y-o filly by Overbury (IRE), the above gelding and a yearling filly by Royal Anthem (USA). 2nd dam COLD EVENING (IRE): unraced; Own sister to GLENELLY GALE (IRE), CAB ON TARGET and Strong Approach; dam of 9 foals; 5 runners; 3 winners: Phar From Frosty (IRE) (g. by Phardante (FR)): 5 wins, £26,177 viz. winner of a N.H. Flat Race; also 4 wins over hurdles and placed 5 times inc. 2nd Tripleprint Bristol Novices' Hurdle, Gr.2 and placed twice over fences. Glacial Evening (IRE): 3 wins over hurdles and £20,140 and placed 6 times and placed over fences; also winner of a point-to-point. Alpheus (IRE): winner over hurdles; also 5 wins in point-to-points. Mawly Day (IRE): unraced; dam of a winner: Kilmurry (IRE): 4 wins, £40,525 viz. winner over hurdles and 3 wins over fences at 5, 2010; also winner of a point-to-point. -

HEADLINE NEWS • 7/27/07 • PAGE 2 of 7

STREET SENSE IN ‘DANDY’ BREEZE HEADLINE p7 NEWS For information about TDN, DELIVERED EACH NIGHT BY FAX AND FREE BY E-MAIL TO SUBSCRIBERS OF call 732-747-8060. www.thoroughbreddailynews.com FRIDAY, JULY 27, 2007 SANFORD WON BY HIS SON FULL BOAT FOR WHITNEY He wasn=t quite as impressive as his sire, who won So competitive is Saturday=s GI Whitney H. that Brass the 1999 GII Sanford S. by nearly 10 lengths, but Jim Hat (Prized), a Grade I winner and good enough to Scatuorchio=s Ready=s Image (More Than Ready) was cross the line second in the world=s richest horse race in dominating enough, taking yesterday=s Saratoga feature 2006, is pegged at 20-1 on Eric Donovan=s morning by four convincing lengths line. A full field of 12 handicap horses has been assem- from Tale of Ekati (Tale of the bled for the $750,000 feature Cat). Wheeled back on 13 and, while trainer Kiaran days= rest off a debut victory McLaughlin was stripped of Apr. 20, Ready=s Image was his chance to win back-to- third as the 7-5 chalk in the back runnings with the retire- GIII Kentucky BC S. at Chur- ment of Invasor (Arg), he has chill May 3. The blinkers went a capable replacement with Ready’s Image on for the July 1 Tremont S. West Point Thoroughbred=s Adam Coglianese at Belmont and the dark bay Flashy Bull (Holy Bull). The charged home a 7 3/4-length four-year-old comes into the winner. -

15.1 Introduction 15.2 West African Oral and Written Traditions

Name and Date: _________________________ Text: HISTORY ALIVE! The Medieval World 15.1 Introduction Medieval cultures in West Africa were rich and varied. In this chapter, you will explore West Africa’s rich cultural legacy. West African cultures are quite diverse. Many groups of people, each with its own language and ways of life, have lived in the region of West Africa. From poems and stories to music and visual arts, their cultural achievements have left a lasting mark on the world. Much of West African culture has been passed down through its oral traditions. Think for a moment of the oral traditions in your own culture. When you were younger, did you learn nursery rhymes from your family or friends? How about sayings such as “A penny saved is a penny earned”? Did you hear stories about your grandparents or more distant ancestors? You can probably think of many ideas that were passed down orally from one generation to the next. Kente cloth and hand-carved Suppose that your community depends on you to furniture are traditional arts in West remember its oral traditions so they will never be Africa. forgotten. You memorize stories, sayings, and the history of your city or town. You know about the first people who lived there. You know how the community grew, and which teams have won sports championships. On special occasions, you share your knowledge through stories and songs. You are a living library of your community’s history and traditions. In parts of West Africa, there are people whose job it is to preserve oral traditions and history in this way. -

Racing in Dubai Sale

AT MEYDAN RACECOURSE ON Thur sday, 20 September ’18 AT 5PM Inspect the horses at Meydan Quarantine (Nofa Stables) Tuesday, 18 September: 7.30-9am and 4-5.30pm Wednesday, 19 September: 7.30-9am and 4-5.30pm Raci ng In Dubai Sale You r golden opp ortuni ty to own a ra cehors e in Du bai... The unusual condition of this sale is that all the horses must remain in the UAE for the next 18 months, enriching the racing scene and providing their new owners with outstanding sport. At the natio n’s five racecourses, chances to win abound. Graduates of this sale have already won more than 100 times, right up to the very highest level. SPONSORED BY AL BASTI EQUIWORLD 1 Grads wh o’ve made t he gra de... No rt h America Bought for: AED 140,000 Winnings so far: AED2,064 ,947 2 RACING IN DUBAI SALE Hawke sbury Bought for: AED 25 0,000 Winnings so far: AED253,000 SPONSORED BY AL BASTI EQUIWORLD 3 Good T rip Bought for: AED 17 0,000 Winnings so far: AED34 7,263 Shil long Bought for: AED 15 0,000 Winnings so far: AED55 7,850 4 RACING IN DUBAI SALE Secret Amb itio n Bought for: AED 150,000 Winnings so far: AED783 ,170 Brave h orses, great sp ort, u nforgett abl e nigh ts... SPONSORED BY AL BASTI EQUIWORLD 5 It could be y ou in t he win ner ’s enclosure... Rave n’s C orner Bought for: AED 13 5,000 Winnings so far: AED68 3,530 Janszo on Bought for: AED 300 ,000 Winnings so far: AED36 9,316 6 RACING IN DUBAI SALE Mo ntsarr at Bought for: AED 200 ,000 Winnings so far: AED42 5,380 Galesburg Bought for: AED 30 ,000 Winnings so far: AED21 7,200 SPONSORED BY AL BASTI EQUIWORLD 7 Ho rnsby Bought for: AED 375 ,000 Winnings so far: AED25 0,062 Dr af ted Bought for: AED 40 ,000 Winnings so far: AED408,899 Street Of Dreams Bought for: AED 120 ,000 Winnings so far: AED268 ,710 8 RACING IN DUBAI SALE Riflesco pe Bought for: AED1 30, 000 Winnings so far: AED1 73, 150 Maybe we should rename it the ‘ Winning In Duba i’ sal e! Town’s Hist ory Bought for: AED 140 ,000 Winnings so far: AED142,3 17 SPONSORED BY AL BASTI EQUIWORLD 9 How to buy a r acehorse.. -

A Performance Guide to Wallace Stevens' Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird As Set by Louise Talma

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 2020 A Performance Guide to Wallace Stevens' Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird as Set by Louise Talma Meredith Melvin Johnson The University of Soutthern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Meredith Melvin, "A Performance Guide to Wallace Stevens' Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird as Set by Louise Talma" (2020). Dissertations. 1787. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1787 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A PERFORMANCE GUIDE TO WALLACE STEVENS’ THIRTEEN WAYS OF LOOKING AT A BLACKBIRD AS SET BY LOUISE TALMA by Meredith Melvin Johnson A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Sciences and the School of Music at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved by: Dr. Christopher Goertzen, Committee Chair Dr. Jonathan Yarrington Dr. Kimberley Davis Dr. Maryann Kyle Dr. Douglas Rust ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Dr. Christopher Goertzen Dr. Jay Dean Dr. Karen S. Coats Committee Chair Director of School Dean of the Graduate School May 2020 COPYRIGHT BY Meredith Melvin Johnson 2020 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT This dissertation presents a two-fold discourse, first to provide a contextual source for singers interested in 20th century composer Louise Talma, and second to provide an analytical guide to Talma’s adaption of Wallace Stevens’ poem Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird for voice, oboe, and piano. -

To Consignors Hip Color & No

Index to Consignors Hip Color & No. Sex Name, Year Foaled Sire Dam Barn 29 Consigned by Amende Place (Lee McMillin), Agent I Broodmare 3895 dk. b./br. m. Salt Loch, 1996 Salt Lake Jolie Scot Barn 29 Consigned by Amende Place (Lee McMillin), Agent II Weanling 4074 ch. c. unnamed, 2005 Van Nistelrooy Don't Answer That Barn 29 Consigned by Amende Place (Lee McMillin), Agent V Broodmare 3807 dk. b./br. m. Magic in the Music, 1995 Dixieland Band Shared Magic Barn 29 Consigned by Amende Place (Lee McMillin), Agent VI Broodmare 3874 b. m. Queen's Castle, 1995 Pleasant Tap Castle Eight Barn 29 Consigned by Amende Place (Lee McMillin), Agent VII Weanling 3934 b. c. unnamed, 2005 Include Sweet Elyse Barn 41 Consigned by Anderson Farms, Agent Stallion prospect 4327 gr/ro. c. Third Sacker, 2001 Maria's Mon De La Cat Barn 41 Consigned by Anderson Farms, Agent for Ellie Boje Farm Broodmare 4256 b. m. Rahy's Hope, 1996 Rahy Roberto's Hope Barn 41 Consigned by Anderson Farms, Agent for Kuehne Racing Broodmare 4249 dk. b./br. m. Princess Pamela, 1999 Binalong Constant Talk Barn 41 Consigned by Anderson Farms, Agent for Sam-Son Farm Broodmare 4416 ch. m. Dixieland Briar, 1999 Dixieland Band Roman Briar Barn 46 Consigned by William Anderson, Agent Broodmare 4317 dk. b./br. m. Superdor, 1993 Cawdor Allerton Barn 48 Consigned by Aspendell, Agent Broodmares 4279 ch. m. Scram, 1990 Stalwart Flaxen 4303 ch. m. Spritz, 1994 Relaunch Supplier Weanlings 4280 b. c. unnamed, 2005 Ride the Rails Scram 4389 ch. -

S U P P L E M E

EUROPEAN BLOODSTOCK NEWS 10k & UNDER SUPPLEMENT EUROPEAN BLOODSTOCK NEWS is delighted to present this special supplement devoted to flat stallions standing in the UK and Ireland at a fee of £10,000 or less in 2018. It is broken into two alphabetical sections, with the advertised stallions appearing first. 2018 Whilst every care has been taken to trace the qualifying sires, EBN takes no responsibility for errors or omissions. Please note that stallions standing at less than €1,000 are not included. All material contained within (excluding supplied advertisements) is the copyright of European Bloodstock News. STALLIONS STANDING FOR £10,000 OR LESS IN 2018 EUROPEAN BLOODSTOCK NEWS ADAAY ALHEBAYEB Kodiac – Lady Lucia (Royal Applause) Dark Angel– Miss Indigo (Indian Ridge) WHITSBURY MANOR STUD • Fee £6,000, 1st Oct SLF TARA STUD • Fee €5,000 Whitsbury Manor Stud stallion Adaay will have his first-crop Alhebayeb was an exceptionally fast and precocious son of foals on the ground this year. The son of Kodiac was extremely Dark Angel. A maiden winner on his debut at two, he soon well–supported with a three-figure book of mares in his first made up into a Stakes performer, finishing second in the season, and that level of popularity will surely continue. His Listed Windsor Castle Stakes at Royal Ascot and winning the own sire is a half-brother to breed–shaping sire Invincible Gr.2 July Stakes on his third start. He demonstrated his Spirit and exerts huge influence in his own right as the sire of versatility by finishing second in the Gr.3 Horris Hill Stakes such stars as Gr.1 Cheveley Park Stakes winner Tiggy Wiggy over seven furlongs on heavy ground later in his juvenile and Gr.2 Celebration Mile Stakes winner Kodi Bear. -

Proverb Instruction in EFL Classrooms

Available online at www.ejal.eu http://dx.doi.org/10.32601/ejal.543781 EJAL Eurasian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 5(1), 57–88 Eurasian Journal of Applied Linguistics A Proverb Learned is a Proverb Earned: Proverb Instruction in EFL Classrooms Nilüfer Can Daşkına * , Çiler Hatipoğlu b† a Hacettepe University, Ankara 06800, Turkey b Middle East Technical University, Ankara 06800, Turkey Received 14 September 2018 Received in revised form 19 February 2019 Accepted 21 February 2019 APA Citation: Can-Daşkın, N., & Hatipoğlu, Ç. (2019). A proverb earned: proverb instruction in EFL classrooms. Eurasion Journal of Applied Linguistics, 5(1), 57–88. Doi: 10.32601/ejal.543781 Abstract This study aims to reveal the situation about proverb instruction in EFL classrooms by seeking future English teachers’ opinions. It is based on the argument that proverbs are an important part of cultural references, figurative, functional and formulaic language; thereby, they lend themselves well to enhancing communicative competence. This study investigates what EFL student-teachers think and feel about English proverb instruction, how they conceptualize proverbs, how they define their knowledge and use of English proverbs, and what they think about the extent to which their English teachers and coursebooks at high school taught English proverbs. In doing so, a questionnaire was designed and administered to freshman EFL student-teachers and semi-structured interviews were conducted with volunteers. The findings revealed that despite those student-teachers’ positive attitudes towards proverb instruction, they did not view their knowledge of English proverbs as well as the teaching of proverbs by their English teachers and coursebooks at high school sufficient enough.