A Performance Guide to Selected Song Cycles of John Harbison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

74TH SEASON of CONCERTS April 24, 2016 • National Gallery of Art PROGRAM

74TH SEASON OF CONCERTS april 24, 2016 • national gallery of art PROGRAM 3:30 • West Building, West Garden Court Inscape Richard Scerbo, conductor Toru Takemitsu (1930 – 1996) Rain Spell Asha Srinivasan (b. 1980) Svara-Lila John Harbison (b. 1938) Mirabai Songs It’s True, I Went to the Market All I Was Doing Was Breathing Why Mira Can’t Go Back to Her Old House Where Did You Go? The Clouds Don’t Go, Don’t Go Monica Soto-Gil, mezzo soprano Intermission Chen Yi (b. 1953) Wu Yu Praying for Rain Shifan Gong-and-Drum Toru Takemitsu Archipelago S. 2 • National Gallery of Art The Musicians Founded in 2004 by artistic director Richard Scerbo, Inscape Chamber Orchestra is pushing the boundaries of classical music in riveting performances that reach across genres and generations and transcend the confines of the traditional concert experience. With its flexible roster and unique brand of programming, this Grammy-nominated group of high-energy master musicians has quickly established itself as one of the premier performing ensembles in the Washington, DC, region and beyond. Inscape has worked with emerging American composers and has a commitment to presenting concerts featuring the music of our time. Since its inception, the group has commissioned and premiered over twenty new works. Its members regularly perform with the National, Baltimore, Philadel- phia, Virginia, Richmond, and Delaware symphonies and the Washington Opera Orchestra; they are members of the Washington service bands. Inscape’s roots can be traced to the University of Maryland School of Music, when Scerbo and other music students collaborated at the Clarice Smith Center as the Philharmonia Ensemble. -

John Harbison's Songs for Baritone: a Performer's Guide

John Harbison‘s Songs for Baritone: A Performer‘s Guide A document submitted to The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2011 by Peter C. Keates B.M.A., University of Oklahoma, 2004 M.M., University of Cincinnati, CCM, 2006 Abstract This document is a performance guide for Words from Paterson and Flashes and Illuminations, John Harbison‘s song cycles for baritone. It confronts the issues of text interpretation and musical style one must address in order to give the most informed performance of these songs. It provides a synthesis of information about the poems and readings of the poetry Harbison set to music, offers insight into Harbison‘s interpretations of the text, and demonstrates how Harbison‘s atonal style and unique compositional techniques provide a successful musical setting for the chosen texts. The guide also discusses performance issues based on personal experience as well as the experience of the composer and other performers. The poetic style of William Carlos Williams, Michael Fried, Czeslaw Milosz, Elizabeth Bishop, and Eugenio Montale are examined. A transcription of an interview with John Harbison is also included. Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 1 I. Paterson ............................................................................................................................................... -

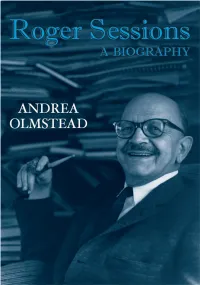

Roger Sessions: a Biography

ROGER SESSIONS: A BIOGRAPHY Recognized as the primary American symphonist of the twentieth century, Roger Sessions (1896–1985) is one of the leading representatives of high modernism. His stature among American composers rivals Charles Ives, Aaron Copland, and Elliott Carter. Influenced by both Stravinsky and Schoenberg, Sessions developed a unique style marked by rich orchestration, long melodic phrases, and dense polyphony. In addition, Sessions was among the most influential teachers of composition in the United States, teaching at Princeton, the University of California at Berkeley, and The Juilliard School. His students included John Harbison, David Diamond, Milton Babbitt, Frederic Rzewski, David Del Tredici, Conlon Nancarrow, Peter Maxwell Davies, George Tson- takis, Ellen Taaffe Zwilich, and many others. Roger Sessions: A Biography brings together considerable previously unpublished arch- ival material, such as letters, lectures, interviews, and articles, to shed light on the life and music of this major American composer. Andrea Olmstead, a teaching colleague of Sessions at Juilliard and the leading scholar on his music, has written a complete bio- graphy charting five touchstone areas through Sessions’s eighty-eight years: music, religion, politics, money, and sexuality. Andrea Olmstead, the author of Juilliard: A History, has published three books on Roger Sessions: Roger Sessions and His Music, Conversations with Roger Sessions, and The Correspondence of Roger Sessions. The author of numerous articles, reviews, program and liner notes, she is also a CD producer. This page intentionally left blank ROGER SESSIONS: A BIOGRAPHY Andrea Olmstead First published 2008 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017, USA Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2008 Andrea Olmstead Typeset in Garamond 3 by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk All rights reserved. -

Johannes Brahms's Ein Deutsches Requiem, Opus 45." Doctoral Dissertation

JOHANNES BRAHMS’S EIN DEUTSCHES REQUIEM: A COMPARISON OF THE REDUCED ORCHESTRATION TECHNIQUES IN JOACHIM LINCKELMANN’S CHAMBER ENSEMBLE VERSION TO BRAHMS’S FOUR HAND PIANO VERSION Michael Aaron Hawley, B.M.E., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2016 APPROVED: Richard Sparks, Major Professor and Chair of the Division of Conducting and Ensembles Stephen F. Austin, Minor Professor Gregory Hobbs, Committee Member Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Vice Provost of the Toulouse Graduate School Hawley, Michael Aaron. Johannes Brahms’s Ein deutsches Requiem: A Comparison of the Reduced Orchestration Techniques in Joachim Linckelmann’s Chamber Ensemble Version to Brahms’s Four-Hand Piano Version. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), December 2016, 265 pp., 29 musical examples, bibliography, 30 titles. Recognizing the challenges small groups have to program a major work, in 2010, Joachim Linckelmann created a chamber ensemble arrangement of Johannes Brahms’s Ein deutsches Requiem. In 1869, J.M. Reiter-Biedermann published Brahms’s four-hand piano arrangement of Ein deutsches Requiem. Brahms’s arrangement serves as an excellent comparison to the chamber ensemble version by Linckelmann, since it can be assumed that Brahms chose to highlight and focus on the parts he deemed the most important. This study was a comparative analysis of the two arrangements and was completed in three stages. The first stage documented every significant change in Joachim Linckelmann’s recent chamber arrangement. The second stage classified each change as either a reduction, reorganization, or elimination. -

Now Again New Music Music by Bernard Rands Linda Reichert, Artistic Director Jan Krzywicki, Conductor with Guest Janice Felty, Mezzo-Soprano Now Again

Network for Now Again New Music Music by Bernard Rands Linda Reichert, Artistic Director Jan Krzywicki, Conductor with guest Janice Felty, mezzo-soprano Now Again Music by Bernard Rands Network for New Music Linda Reichert, Artistic Director Jan Krzywicki, Conductor www.albanyrecords.com TROY1194 albany records u.s. 915 broadway, albany, ny 12207 with guest Janice Felty, tel: 518.436.8814 fax: 518.436.0643 albany records u.k. box 137, kendal, cumbria la8 0xd mezzo-soprano tel: 01539 824008 © 2010 albany records made in the usa ddd waRning: cOpyrighT subsisTs in all Recordings issued undeR This label. The story is probably apocryphal, but it was said his students at Harvard had offered a prize to anyone finding a wantonly decorative note or gesture in any of Bernard Rands’ music. Small ensembles, single instrumental lines and tones convey implicitly Rands’ own inner, but arching, songfulness. In his recent songs, Rands has probed the essence of letter sounds, silence and stress in a daring voyage toward the center of a new world of dramatic, poetic expression. When he wrote “now again”—fragments from Sappho, sung here by Janice Felty, he was also A conversation between composer David Felder and filmmaker Elliot Caplan about Shamayim. refreshing his long association with the virtuosic instrumentalists of Network for New Music, the Philadelphia ensemble marking its 25th year in this recording. These songs were performed in a 2009 concert for Rands’ 75th birthday — and offer no hope for winning the prize for discovering extraneous notes or gestures. They offer, however, an intimate revelation of the composer’s grasp of color and shade, his joy in the pulsing heart, his thrill at the glimpse of what’s just ahead. -

Psaudio Copper

Issue 116 JULY 27TH, 2020 “Baby, there’s only two more days till tomorrow.” That’s from the Gary Wilson song, “I Wanna Take You On A Sea Cruise.” Gary, an outsider music legend, expresses what many of us are feeling these days. How many conversations have you had lately with people who ask, “what day is it?” How many times have you had to check, regardless of how busy or bored you are? Right now, I can’t tell you what the date is without looking at my Doug the Pug calendar. (I am quite aware of that big “Copper 116” note scrawled in the July 27 box though.) My sense of time has shifted and I know I’m not alone. It’s part of the new reality and an aspect maybe few of us would have foreseen. Well, as my friend Ed likes to say, “things change with time.” Except for the fact that every moment is precious. In this issue: Larry Schenbeck finds comfort and adventure in his music collection. John Seetoo concludes his interview with John Grado of Grado Labs. WL Woodward tells us about Memphis guitar legend Travis Wammack. Tom Gibbs finds solid hits from Sophia Portanet, Margo Price, Gerald Clayton and Gillian Welch. Anne E. Johnson listens to a difficult instrument to play: the natural horn, and digs Wanda Jackson, the Queen of Rockabilly. Ken hits the road with progressive rock masters Nektar. Audio shows are on hold? Rudy Radelic prepares you for when they’ll come back. Roy Hall tells of four weddings and a funeral. -

An Analysis and Performance Considerations for John

AN ANALYSIS AND PERFORMANCE CONSIDERATIONS FOR JOHN HARBISON’S CONCERTO FOR OBOE, CLARINET, AND STRINGS by KATHERINE BELVIN (Under the Direction of D. RAY MCCLELLAN) ABSTRACT John Harbison is an award-winning and prolific American composer. He has written for almost every conceivable genre of concert performance with styles ranging from jazz to pre-classical forms. The focus of this study, his Concerto for Oboe, Clarinet, and Strings, was premiered in 1985 as a product of a Consortium Commission awarded by the National Endowment of the Arts. The initial discussions for the composition were with oboist Sara Bloom and clarinetist David Shifrin. Harbison’s Concerto for Oboe, Clarinet, and Strings allows the clarinet to finally be introduced to the concerto grosso texture of the Baroque period, for which it was born too late. This document includes biographical information on John Harbison including his life and career, compositional style, and compositional output. It also contains a brief history of the Baroque concerto grosso and how it relates to the Harbison concerto. There is a detailed set-class analysis of each movement and information on performance considerations. The two performers as well as the composer were interviewed to discuss the commission, premieres, and theoretical/performance considerations for the concerto. INDEX WORDS: John Harbison, Concerto for Oboe, Clarinet, and Strings, clarinet concerto, oboe concerto, Baroque concerto grosso, analysis and performance AN ANALYSIS AND PERFORMANCE CONSIDERATIONS FOR JOHN HARBISON’S CONCERTO FOR OBOE, CLARINET, AND STRINGS by KATHERINE BELVIN B.M., Tennessee Technological University, 2004 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2009 © 2009 Katherine Belvin All Rights Reserved AN ANALYSIS AND PERFORMANCE CONSIDERATIONS FOR JOHN HARBISON’S CONCERTO FOR OBOE, CLARINET, AND STRINGS by KATHERINE BELVIN Major Professor: D. -

Emmanuel Music Bach Cantata Series, 2007-2008

Emmanuel Music Bach Cantata Series, 2007-2008 With the joyful sound of Emmanuel Music violins, oboes, flutes and organ, the 2007-08 Bach Signature Season began on Sunday, September 16. The occasion called for a jubilant performance of J. S. Bach’s Cantata BWV 163, Nur jedem das Seine! featuring soloists Kendra Colton, Krista River, Frank Kelley and Donald Wilkinson. This cantata spotlights not only the music of Bach, but also the poetry of librettist Salomo Franck. A frequent Bach collaborator, Franck combined his poetic talents with duties as head of the Weimar Mint. In the vibrant bass aria of BWV 163, sung by Wilkinson, Franck employs coin symbolism, urging God to stamp his image on the poet’s heart instead of the head of Caesar. The above is just a sample of what is in store for this year’s cantata audiences. Emmanuel Music presents a full Bach cantata each Sunday from September through May at the 10 am Sunday liturgy at Emmanuel Church, 15 Newbury Street, Boston, where Emmanuel Music is the Ensemble-in-Residence. Its renowned Artistic Director is Craig Smith, who has conducted his musicians with warmth and inspiration for 37 years. While there is no admission charge for each cantata, voluntary contributions are most welcome. Sharing the podium with Smith during the 2007-08 cantata season are such notable conductors as Michael Beattie, John Harbison, Edith Ho, Leonard Matczynski, Scott Metcalfe, James Olesen and Ryan Turner. Bach cantatas at Emmanuel have provided musical nourishment to many-- musicians as well as listeners. Such luminaries as Seiji Ozawa of the Boston Symphony and Christopher Hogwood of the Handel & Haydn Society have also conducted the Orchestra and Chorus of Emmanuel Music in Bach cantatas. -

Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 11-28-2012 Concert: Ithaca College Sinfonietta Ithaca College Sinfonietta James Mick Tiffany Lu Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Ithaca College Sinfonietta; Mick, James; and Lu, Tiffany, "Concert: Ithaca College Sinfonietta" (2012). All Concert & Recital Programs. 3792. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/3792 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Ithaca College Sinfonietta Dr. James Mick, conductor Tiffany Lu, assistant conductor Ford Hall Wednesday November 28th, 2012 7:00 pm Program Overture to Nabucco Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) "Nimrod" from The Enigma Variations Edward Elgar (1857-1934) String Symphony No. 10 in B minor, MWV N Felix Mendelssohn 10 (1809-1847) Adagio – Allegro – Più presto Hungarian Dances, WoO 1 Johannes Brahms No. 7 in F Major: Allegretto - Vivo (1833-1897) No. 3 in F Major: Allegretto No. 5 in G minor: Allegro - Vivo Suite from The Firebird Igor Stravinsky VI. Berceuse (1882-1971) VII. Finale This concert is being webstreamed live at http://www.ithaca.edu/music/live/ Biographies Dr. James Mick is an assistant professor of music education at Ithaca College in upstate New York. He teaches courses in string pedagogy and rehearsal techniques, helps manage junior string student teachers, supervises underclassman music education majors, and conducts the Ithaca College Sinfonietta, a full-orchestra consisting primarily of non-music majors. -

The New York Virtuoso Singers

Merkin Concert Hall at Kaufman Center Presents The New York Virtuoso Singers Announcing the 25th Anniversary Season Merkin Concert Hall Performances – 2012-13 Concerts Feature 25 Commissioned Works by Major American Composers The New York Virtuoso Singers, Harold Rosenbaum, Conductor and Artistic Director, have announced Merkin Concert Hall dates for their 2012-13 concert season. This will be the group’s 25th anniversary season. To celebrate, they will present concerts on October 21, 2012 and March 3, 2013 at Kaufman Center’s Merkin Concert Hall, 129 West 67th St. (btw Broadway and Amsterdam) in Manhattan, marking their return to the hall where they presented their first concert in 1988. These concerts will feature world premieres of commissioned new works from 25 major American composers – Mark Adamo, Bruce Adolphe, William Bolcom, John Corigliano, Richard Danielpour, Roger Davidson, David Del Tredici, David Felder, John Harbison, Stephen Hartke, Jennifer Higdon, Aaron Jay Kernis, David Lang, Fred Lerdahl, Thea Musgrave, Shulamit Ran, Joseph Schwantner, Steven Stucky, Augusta Read Thomas, Joan Tower, George Tsontakis, Richard Wernick, Chen Yi, Yehudi Wyner and Ellen Taaffe Zwilich. Both concerts will also feature The Canticum Novum Youth Choir, Edie Rosenbaum, Director. The Merkin Concert Hall dates are: Sunday, October 21, 2012 at 3 pm - 25th Anniversary Celebration Pre-concert discussion with the composers at 2:15 pm World premieres by Jennifer Higdon, George Tsontakis, John Corigliano, David Del Tredici, Shulamit Ran, John Harbison, Steven Stucky, Stephen Hartke, Fred Lerdahl, Chen Yi, Bruce Adolphe and Yehudi Wyner – with Brent Funderburk, piano. More about this concert at http://kaufman-center.org/mch/event/the-new-york-virtuoso- singers. -

The Great Gatsby – Opening of Chapter 3

The Great Gatsby – Opening of Chapter 3 The Great Gatsby is a novel by F. Scott Fitzgerald, set in 1920s America. It is narrated by Nick Carraway, a man in his late 20s, who has moved to Long Island to commute to his job in New York City trading bonds. He moves next door to Jay Gatsby, a man who has earned a reputation for an extravagant lifestyle but is a somewhat enigmatic figure. At this point in the novel, Nick hasn’t even met Gatsby, despite hearing a lot about him. There was music from my neighbor’s house through the summer nights. In his blue gardens men and girls came and went like moths among the whisperings and the champagne and the stars. At high tide in the afternoon I watched his guests diving from the tower of his raft, or taking the sun on the hot sand of his beach while his two motor-boats slit the waters of the Sound, drawing aquaplanes over cataracts of foam. On week-ends his Rolls- Royce became an omnibus, bearing parties to and from the city between nine in the morning and long past midnight, while his station wagon scampered like a brisk yellow bug to meet all trains. And on Mondays eight servants, including an extra gardener, toiled all day with mops and scrubbing-brushes and hammers and garden-shears, repairing the ravages of the night before. Every Friday five crates of oranges and lemons arrived from a fruiterer in New York — every Monday these same oranges and lemons left his back door in a pyramid of pulpless halves. -

By Seamus Heaney

Irish Human Rights Commission Writer & Righter By Seamus Heaney Fourth IHRC Annual Human Rights Lecture, 9 December 2009 First published June 2010 By Irish Human Rights Commission 4th Floor, Jervis House Jervis Street Dublin 1 Copyright © of text of Writer & Righter is the sole property of Seamus Heaney Copyright © of publication belongs to the Irish Human Rights Commission ISBN 978-0-9558048-4-7 The Irish Human Rights Commission (IHRC) was established, under statute in 2000, to promote and protect human rights in Ireland. The human rights that the IHRC protects are the rights, liberties and freedoms guaranteed under the Irish Constitution and the international agreements, treaties and conventions to which Ireland is a party. All human beings are born free & equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason & conscience & should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. www.ihrc.ie 2 & 3 Preface As one of Ireland’s most distinguished poets and prominent advocates for human rights, we invited Seamus Heaney to give our fourth Annual Human Rights Lecture. We considered it an honour when he accepted our invitation. The theme Seamus Heaney chose was the relevance of poetry in times of societal upheaval and unrest. Was it ethical to create poetry when a country or people were in turmoil? Was it ‘right on’ to ‘write on’? He particularly highlighted the differences between the sedentary w-r-i-t-e-r-s and the pro-active r-i-g-h-t-e-r-s, the former whose job it is to reflect and the latter whose role it is to take action.