Reviewandreask.Demetriades(Ed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monastery of Kykkos

Monastery of Kykkos 1 The monastery of the Virgin of Kykkos is located at an altitude of approximately 1,200 meters, about one kilometer from mountain Kykkos, a 1,318 m high peak in the western part of the Troodos range. That peak is also known by the name Throni or Throni of Panagia. The monastery is the most famous and rich among the active Cypriot monasteries of our time. It is also one of the most important in terms of history as well as national and social work. The Holy Monastery of Panagia of Kykkos was founded around the end of the 11th century by Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, and since then has housed the icon of the Virgin reputedly painted by Apostle Luke. According to the tradition concerning the establishment of the Monastery, a virtuous hermit called Esaias used to live in a cave on the mountain of Kykkos. One day, Manuel Boutomites, the Byzantine governor of the island, who was spending his summer holidays at a village in the Marathasa valley went hunting and was lost in the forest. He came upon the hermit and asked him how he could go back. Esaias wished to avoid all things of this world and so did not reply. His attitude angered Boutomites, who resorted to verbal and even physical abuse. Shortly afterwards, Boutomites was taken ill with an incurable disease. This led him to recall his inhuman behaviour towards Esaias and asked God to make him well so that he could go to the hermit and ask him for his forgiveness. -

Cyprus Tourism Organisation Offices 108 - 112

CYPRUS 10000 years of history and civilisation CONTENTS CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 CYPRUS 10000 years of history and civilisation 6 THE HISTORY OF CYPRUS 8200 - 1050 BC Prehistoric Age 7 1050 - 480 BC Historic Times: Geometric and Archaic Periods 8 480 BC - 330 AD Classical, Hellenistic and Roman Periods 9 330 - 1191 AD Byzantine Period 10 - 11 1192 - 1489 AD Frankish Period 12 1489 - 1571 AD The Venetians in Cyprus 13 1571 - 1878 AD Cyprus becomes part of the Ottoman Empire 14 1878 - 1960 AD British rule 15 1960 - today The Cyprus Republic, the Turkish invasion, 16 European Union entry LEFKOSIA (NICOSIA) 17 - 36 LEMESOS (LIMASSOL) 37 - 54 LARNAKA 55 - 68 PAFOS 69 - 84 AMMOCHOSTOS (FAMAGUSTA) 85 - 90 TROODOS 91 - 103 ROUTES Byzantine route, Aphrodite Cultural Route 104 - 105 MAP OF CYPRUS 106 - 107 CYPRUS TOURISM ORGANISATION OFFICES 108 - 112 3 LEFKOSIA - NICOSIA LEMESOS - LIMASSOL LARNAKA PAFOS AMMOCHOSTOS - FAMAGUSTA TROODOS 4 INTRODUCTION Cyprus is a small country with a long history and a rich culture. It is not surprising that UNESCO included the Pafos antiquities, Choirokoitia and ten of the Byzantine period churches of Troodos in its list of World Heritage Sites. The aim of this publication is to help visitors discover the cultural heritage of Cyprus. The qualified personnel at any Information Office of the Cyprus Tourism Organisation (CTO) is happy to help organise your visit in the best possible way. Parallel to answering questions and enquiries, the Cyprus Tourism Organisation provides, free of charge, a wide range of publications, maps and other information material. Additional information is available at the CTO website: www.visitcyprus.com It is an unfortunate reality that a large part of the island’s cultural heritage has since July 1974 been under Turkish occupation. -

Visitnicbooklet.Pdf

Nicosia offers a completely different experience from the popular coastal cities of Cyprus. Centrally located on the island, Nicosia serves as the adminis- trative, political, financial and cultural capital of Cyprus. Nicosia may not have sandy beaches to offer, but its visitors are more than compensated by a wealth of cultural attractions that combine authentic Cypriot culture with modern European amenities. Nicosia is an attractive, enticing city; ideal for expe- riencing what modern Cyprus is all about. There are great restaurants here, from traditional taverns with bouzouki players and generous portions of meze, to Guided Walking Tours pg. 2 ultramodern, fashionable joints, where young Cypriots dance the night away. Attractions and Sightseeing pg. 2 The country’s best museum is here, with its impressive Museums and Galleries in Nicosia pg. 6 archaeological collection. The Old City with its sur- rounding star-shaped fortifications is a labyrinth of Theatres Arts pg.10 & narrow streets, teeming with churches, mosques and beautiful, often dilapidated colonial houses. Modern Architecture pg.10 Gastronomy pg.10 The New City outside the walls is in a constant state of development, with modern buildings and structures Nicosia Regional Atractions pg.12 that add a distinctive European character and cul- ture. The regional countryside of Nicosia is full of di- verse attractions from all periods of Cyprus’ ancient, medieval and recent history. 1 Guided Walking Tours Attractions and Sightseeing The best way to experience all Nicosia’s Whatever part of Nicosia you are staying most important sights and landmarks is by in, there are sure to be plenty of good walking. -

Where to … Larnaka

WHERE TO … LARNAKA –Past & Present treasures revealed– WHERE TO… WHERE TO… 2 LARNAKA LARNAKA 3 Past & Present treasures revealed content welcome Past & Present treasures revealed WHERE to… WHERE to… STAY VISIT CTO Licensed Religious Sites Accommodation Establishments Cultural Sites Rural Larnaka 06 11 WHERE to… WHERE to… the chairman of the larnaka tourism Born and raised in Larnaka, he is pas- hope that you will begin to understand Board welcomes you to larnaka. sionate about his home, “I love every why this is the feeling that so many single thing about Larnaka. I strongly people from Larnaka carry in their GO TaSTE Dinos Lefkaritis, endeavours along believe that Larnaka is the most beau- hearts. with the other board members to tiful city in Cyprus.” highlight this beautiful, historical re- The charismatic personalities, the hos- Beaches . Watersports Dining gion. As you browse through our guide, we pitable warmth, as with good food is Leisure . Diving & Cruising Drinking Cycling . Nature Trails Events Diary 52 76 WHERE to… WHERE to… SHOP FIND Retail Therapy Tourist Information Maps 84 88 Published by Where To Cyprus for the Larnaka Tourism Board. Where To Cyprus endeavor to make every effort to ensure that the contents of this publica- tion are accurate at the time of publication. The editorial materials and views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of Where To Cyprus, its publish- ers or partners. Where To Cyprus Reserve All Rights to this publication and its content and it may not be reproduced in full or in part without expressed written permission of Where To Cyprus. -

ENG COVERS Divided 2/21/08 7:50 PM Page 1

ENG COVERS Divided 2/21/08 7:50 PM Page 1 Cyprus Spiritual And CYPRUS TOURISM ORGANISATION 19 Lemesos Avenue, P.O.Box: 24535, 1390 Lefkosia, Cyprus Cultural Tel: +357 22 69 11 00 Fax: +357 22 33 16 44 Email: [email protected] Journeys www.visitcyprus.com ENG COVERS Divided 2/21/08 7:50 PM Page 2 Agios Nikolaos Stegis church Agios Ioannis Lampadistis Museum Panagia tou Araka Monastery Monuments of UNESCO Monuments of UNESCO Monuments of UNESCO Solea region Marathasa region Pitsilia region ● Nikitari: Church of Panagia tis ● Kalopanagiotis: Monastery of Agios ● Lagoudera: Monastery of Panagias Asinou (Virgin of Asinou) ● Galata: Ioannis Lampadistis (St. John tou Araka (the Virgin of Araka) Church of Panagia tis Podithou Lampadistis) ● Moutoulas: Church of ● Platanistasa: Holy Cross of (Virgin of Podithou) ● Kakopetria: the Virgin Mary ● Pedoulas: Church Agiasmati ● Pelendri: Church of the Church of Agios Nikolaos tis Stegis of Archangelos Michael (Archangel Holy Cross ● Palaichori: Church of (Saint Nicholas of the Roof) Michael) the Transfiguration of the Saviour LEFKOSIA NICOSIA Peristerona Monastery of Panagia tou Kykkou Kalopanagiotis Panagia LARNAKA Tala yprus, that “ethereal and blessed Emba land” that stands apart, serene and PAFOS sacred with an irresistible fascination, Geroskipou C LEMESOS ourneys LIMASSOL J is a paradise full of natural beauty, history, mem- ories and culture. A most surprising feature is its Byzantine art in Cyprus West Of density of monuments of religious devotion. It is ● ● an island of distinctive aura and charm, where the Peristerona: Church of Saints Barnabas and Hilarion Kalopanagiotis: ● aith whole spectrum of Christianity’s historical and Monastery of Saint John Lampadistis Monastery of the Virgin Mary of Kykkos F ● Panagia ● Tala ● Emba ● Kato Pafos ● Geroskipou cultural development can be seen, from inception AN INTRODUCTION TO A to the present day. -

King's Research Portal

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by King's Research Portal King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.12681/byzsym.15492 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Bouras-Vallianatos, P. (2017). Review of Andreas K. Demetriades (ed.), iatrosophikón.: Folklore Remedies from a Cyprus Monastery: Original text and parallel translation of Codex Machairas A.18. Byzantina Symmeikta, 27, 485-498. DOI: 10.12681/byzsym.15492 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Download the E4 Nature Trail

ils tra ure nat d other Follow the E4 an us. pr Cy EUROPEAN LONG DISTANCE PATH E4 INTRODUCTION The European long distance path E4 was extended to Cyprus following a proposal by the Greek Ramblers Association to the European Ramblers Association, the coordinating body of the European Network of long distance paths. The main partners in Cyprus are the Cyprus Tourism Organisation and the Forestry Department. The path starts at Gibraltar, passes through Spain, France, Switzerland, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Bulgaria, mainland Greece, the Greek island of Crete, to the island of Cyprus. In its Cyprus section, European path E4 connects Larnaka and Pafos international airports. Along the route, it traverses Troodos mountain range, Akamas peninsula and long stretches of cural areas, along regions of enhanced natural beauty and high ecological, historic, archaeological, cultural and scientific value. Few people have the time or the stamina to tackle the whole route in one go. The information given here is a general outline, to assist ramblers identify the path route. It is by no means a detailed description of all aspects of covered areas. Ramblers are strongly advised to research further any path section(s) to be attempted, with particular emphasis in the availability and proximity of overnight licensed accommodation establishments, especially in remote mountain and rural areas. It should be stressed that the route by no means represents all that Cyprus has to offer the rambler. It is primarily designed as cross- country route, and as such is inevitably selective, missing out some fine landscapes and/or cultural sites. It does however provide a sampler of the scenic and cultural variety that is Cyprus. -

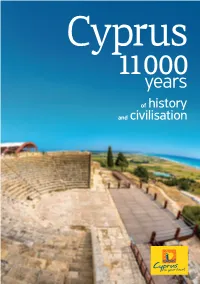

Cyprus 11000 Years of History

Contents Introduction 5 Cyprus 11000 years of history and civilisation 6 The History of Cyprus 7-17 11500 - 10500 BC Prehistoric Age 7 8200 - 1050 BC Prehistoric Age 8 1050 - 480 BC Historic Times: Geometric 9 and Archaic Periods 475 BC - 395 AD Classical, Hellenistic and Roman Periods 10 395 - 1191 AD Byzantine Period 11-12 1192 - 1489 AD Frankish Period 13 1489 - 1571 AD The Venetians in Cyprus 14 1571 - 1878 AD Cyprus becomes part of the Ottoman Empire 15 1878 - 1960 AD British rule 16 1960 - Today The Republic of Cyprus, the Turkish 17 invasion, European Union entry Lefkosia (Nicosia) 18-39 Lemesos (Limassol) 40-57 Larnaka 58-71 Pafos 72-87 Ammochostos (Famagusta) 88-95 Troodos 96-110 Aphrodite Cultural Route Map 111 Wine Route Map 112-113 Cyprus Tourism Offices 114 Cyprus Online www.visitcyprus.com Our official website provides comprehensive information on the major attractions of Cyprus, complete with maps, an updated calendar of events, a detailed hotel guide, downloadable photos and suggested itineraries. You will also find a list of tour operators covering Cyprus, information on conferences and incentives and a wealth of other useful information. Lefkosia Lemesos - Larnaka Limassol Pafos Ammochostos - Troodos 4 Famagusta Introduction Cyprus is a small country with a long history and rich culture. It is not surprising that UNESCO included the Pafos antiquities, Choirokoitia Neolithic settlement and ten of the Byzantine period churches of Troodos on its list of World Heritage Sites. The aim of this publication is to help visitors discover the cultural heritage of Cyprus. The qualified personnel at any of our Information Offices will be happy to assist you in organising your visit in the best possible way. -

Music of the Turkish Cypriots: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow

MUSIC OF THE TURKISH CYPRIOTS: YESTERDAY, TODAY AND TOMORROW Section 4. Theory and history of culture Abdoulline Ilias, Lecturer at Department of Fine Arts Education. Near East University. Nicosia. Northen Cyprus E‑mail: [email protected] MUSIC OF THE TURKISH CYPRIOTS: YESTERDAY, TODAY AND TOMORROW Abstract: This article deals with the formation and development of musical culture of the Turkish Cypriots as an essential component of ethnos of Cyprus. Keywords: Island of Cyprus, ethnic cultural traditions of Cyprus, music of the Turkish Cypriots. The origins of musical culture of the peoples It should be noted that the studies devoted to from the Near and Middle East allow to speak of ex- the folk music and dance traditions of various ethnic istence of the Middle Eastern Mediterranean musi- groups in Cyprus began at the end of XIX century. cal tradition as a uniform system of artistic means, However, folklorists paid more attention in their figurative themes, genres and etc., which originate studies to lyrics rather than to musical content. from the ancient depths of history. Thus, researcher Panicos Giorgoudes states that The timeframe of this process can be determined “systematic studies of the Turkish Cypriots tradi- just approximately, but it becomes clear that the tional music developed poorly, notwithstanding modern musical art of Cyprus, which is now per- several articles about Cypriot music published by ceived as traditional, was formed already in “histori- musicologists and Theodulos Kallinikos’ collection cal” time, in connection with spread of the national of Cypriot songs in 1951. Besides, many research- Turkish culture on the Cypriot land. -

Authentic Cyprus Guide.Pdf

introShort This guidebook has been designed to provide visitors with an extensive insight into the delightful world of rural Cyprus. This is a world apart from the beaches and tourist hotspots. Here, timeless villages, tiny remote painted churches, stunning scenery, forested mountain trails and a way of life that has hardly changed over the past centuries, are just waiting to be discovered. The first part of this book provides general information on rural Cyprus, its history, traditions, cultures, flora and fauna, places of interest and more. The second half of the book, details 15 recommended driving excursions. All of the routes can be accomplished easily within a day’s drive in a regular car, yet all have something different to offer. The routes highlight points-of-interest along the way and all start and finish on one of the main roads. These routes are also ideal for organised group tours with small buses. The routes include places to stop for walking, cycling, bird watching, fresh-water fishing or to simply explore the countryside and charming villages. All that’s needed is a good road map, a sunhat, plenty of water, comfortable walking shoes and a spirit of adventure. NOTE: The spellings of all place-names conform to those indicated on the road signs. However, in some cases, these may vary from those shown on your road map. Contents Useful Information 3 Welcome to Rural Cyprus 4 Natural Environment 8 Cultural Heritage 12 Rural Crafts and Skills 18 Food and Wine 22 Rural Accommodation 28 Countryside Activities 32 Religious and Local -

Cyprus Tourism Organisation

Cyprus Spiritual and Cultural Journeys 1 CHRISTIANITY’S HISTORICAL CROSSROAD yprus, that “ethereal and blessed land” that stands apart, serene and sacred with an irresistible Journeys of fascination,is a paradise full of natural beauty, history, memories and culture. A most sur- prisingC feature is its density of monuments of Faith religious devotion. It is an island of distinctive aura and charm, where the whole spectrum of Christianity’s historical and cultural devel- opment can be seen, from inception to the present day. beauty, where according to Greek AN INTRODUCTION TO A myth the goddess Aphrodite was born - was SPIRITUAL WORLD chosen as the first place to receive the great 2 CHRISTIANITY’S HISTORICAL CROSSROAD message of the new faith on the advent of dedicated to prayer and devotion, but also p Situated on a steep hill, Christianity. Cyprus became the gateway through the plethora of holy men connected Stavrovouni Monastery offers a panorama of the through which the message of the Gospels with the saintly island, thus endowing it with surrounding countryside. spread throughout the length and breadth of the expression“Cyprus the island of saints”. the Ecumene. The first mission of the apos- It is no coincidence that Cyprus - the island of tles Paul and Barnabas (the latter of Cypriot saints”. descent) occurred here in accordance with the Τhe Office of the pilgrimage tours of the will and wish of God: “..being sent forth by the Church of Cyprus ([email protected]. Holy Ghost, departed unto Seleucia; and from cy, tel. 35722554600, fax. 35722346254) opens thence they sailed to Cyprus” (Acts 12, 4). -

Travellers Handbook CYPRUS TRAVELLERS HANDBOOK

www.visitcyprus.com Travellers Handbook CYPRUS TRAVELLERS HANDBOOK EVERYTHING YOU WANT TO KNOW ABOUT YOUR STAY IN CYPRUS CYPRUS TOURISM ORGANISATION CYPRUS TRAVELLERS HANDBOOK The Travellers Handbook is intended to offer the holidaymaker and visitor valuable information about the island, so as to get the most out of their stay in Cyprus. Providing the reader with facts and advice, this Handbook is designed to assist to the planning of a trip to Cyprus and to offer information, that will make one’s stay a most pleasant and enjoyable one. MAY YOUR VISIT IN CYPRUS BE A MEMORABLE ONE Cyprus Online: www.visitcyprus.com The Official Website of the Cyprus Tourism Organisation provides comprehensive information on the major attractions of Cyprus, complete with maps, updated calendar of events, detailed hotel guide, downloadable photos, travel planner to help you organise a trip to Cyprus and suggested itineraries. You will also find lists of tour operators selling Cyprus, information on conferences and incentives, and a wealth of useful information. In this leaflet all place names have been converted into Latin characters according to the official System of Transliteration of the Greek alphabet, i.e. LEFKOSIA = NICOSIA, LEMESOS = LIMASSOL, AMMOCHOSTOS = FAMAGUSTA Notes on pronunciation: ‘ai’: as in English egg ‘oi’, ‘ei’, ‘y’: as in English India ‘ou’: as in English tour TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE General Information on Cyprus . .7-13 Cyprus Tourism Organisation . .13 Tourist Information Offices in Cyprus . .13-14 Cyprus Tourism Organisation (CTO) Offices abroad . .14-17 A Accessibility . .18 Accommodation (Hotels–Hotel Reservations) . .19-20 Air and Sea Temperatures, Sunshine, Raindays .