Pathology of Small Airways

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Report: What Is the Real Cause of Death from Acute Chlorine Exposure in an Asthmatic Patient? Toprak S1 and Kalkan EA2*

Toprak and Kalkan. Int J Respir Pulm Med 2016, 3:045 International Journal of Volume 3 | Issue 2 ISSN: 2378-3516 Respiratory and Pulmonary Medicine Case Report: Open Access A Case Report: What is the Real Cause of Death from Acute Chlorine Exposure in an Asthmatic Patient? Toprak S1 and Kalkan EA2* 1Forensic Medicine Department, Bulent Ecevit University, Turkey 2Forensic Medicine Department, Canakkale Onsekiz Mart University, Turkey *Corresponding author: Esin Akgul Kalkan, MD, Assistant Professor, Canakkale Onsekiz Mart University, Faculty of Medicine, Forensic Medicine Department, Canakkale Onsekiz Mart Universitesi, Tip Fakultesi, Adli Tip Anabilim Dali, 17020, Canakkale, Turkey, Tel: +90 532 511 12 97, +90 286 218 00 18/2777, E-mail: [email protected] with a mixture of various chemicals including bleach and an acid Abstract containing product (hydrochloric acid). According to witnesses, her This case report presents an acute and chronic inflammation symptoms include cough, shortness of breath along with red tearing process at the same time and resulted in death following exposure eyes. She is a non-smoker and has no significant medical history other to chlorine gas. A 65-years-old woman died shortly after cleaning than asthma. She was declared dead when she arrives to hospital. her bathroom with a mixture of various chemicals including bleach and an acid containing product. She was declared dead when she The decedent was 155 cm tall and weighed 67 kg. The external arrives to hospital. She is a non-smoker and has no significant findings were unremarkable. Internally the left and right lungs medical history other than asthma. -

Diffuse Panbronchiolitis Is Not Restricted to East Asia—A Mini Literature Review

Review Interstitial Lung Disease Diffuse Panbronchiolitis is not Restricted to East Asia—a Mini Literature Review Ram Kumar Mishra Epidemiology and HEOR Team, ODC 3, Tata Consultancy Services, Thane (W), Maharashtra, India DOI: https://doi.org/10.17925/USRPD.2017.12.02.30 iffuse panbronchiolitis (DPB) is a rare inflammatory lung disease, and is well recognized in East Asian countries like Japan, China, Taiwan and Korea. Over the years, sporadic DPB cases have been reported worldwide from other countries. This literature review presents an D overview of 48 DPB cases from other regions of the world including the US, European countries and Australia. Identification of DPB cases from different racial groups across the globe indicates toward a need to educate pulmonologists to correctly diagnose and initiate treatment. Keywords Diffuse panbronchiolitis (DPB) is a rare inflammatory lung disease. It was first identified in 1969 and is Diffuse panbronchiolitis, erythromycin, interstitial well recognized in East Asian countries such as Japan, China, Taiwan, and Korea.1 ‘Diffuse’ and ‘pan’ lung disease, macrolide therapy, rare disease words in the name indicate ‘presence of lesions through both the lungs,’ and inflammation in all layers of bronchioles. Disclosure: Ram Kumar Mishra has nothing to declare in relation to this article. Opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own findings and do At the time of its discovery, DPB had poor prognosis because of recurrent respiratory infections not in any manner reflect or represent the view of the organization to which he is affiliated. leading to respiratory failure. In the years following the initial description of DPB in Japan, cases were Compliance with Ethics: This study involves a review of also identified in other parts of Asia including China and Taiwan, thus giving it recognition as a distinct the literature and did not involve any studies with human clinical entity. -

Vocal Cord Dysfunction: Analysis of 27 Cases and Updated Review of Pathophysiology & Management

THIEME Original Research 125 Vocal Cord Dysfunction: Analysis of 27 Cases and Updated Review of Pathophysiology & Management Shibu George1 Sandeep Suresh2 1 Department of ENT, Government Medical College, Kottayam, Kerala, India Address for correspondence ShibuGeorge,MS,DNB,Charivukalayil 2 Department of ENT, Little Flower Hospital, Ernakulam, Kerala, India (House), Ettumanoor, Kottayam 686631, Kerala, India (e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]). Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2019;23:125–130. Abstract Introduction Vocal cord dysfunction is characterized by unintentional paradoxical vocal cord movement resulting in abnormal inappropriate adduction, especially during inspiration; this predominantly manifests as unresponsive asthma or unexplained stridor. It is prudent to be well informed about the condition, since the primary presentation may mask other airway disorders. Objective This descriptive study was intended to analyze presentations of vocal cord dysfunction in a tertiary care referral hospital. The current understanding regarding the pathophysiology and management of the condition were also explored. Methods A total of 27 patients diagnosed with vocal cord dysfunction were analyzed based on demographic characteristics, presentations, associations and examination findings. The mechanism of causation, etiological factors implicated, diagnostic considerations and treatment options were evaluated by analysis of the current literature. Results Therewasastrongfemalepredilection noted among the study population (n ¼ 27), which had a mean age of 31. The most common presentations were stridor Keywords (44%) and refractory asthma (41%). Laryngopharyngeal reflux disease was the most ► Vocal Cord common association in the majority (66%) of the patients, with a strong overlay of Dysfunction anxiety, demonstrable in 48% of the patients. ► paradoxical vocal Conclusion Being aware of the condition is key to avoid misdiagnosis in vocal cord cord motion dysfunction. -

Diffuse Panbronchiolitis

C M Chu et al • Diffuse Panbronchiolitis DIFFUSE PANBRONCHIOLITIS : A MIMICKER OF CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE Dr. Chung-ming Chu, MBBS(HK) Dr. Man-fuk Leung, MBBS(HK) FHKCP FHKAM FHKCP FHKAM(Medicine) (Medicine), FRCP(Edin) Senior Medical Officer Consultant and Chief of Service Dr. Cho-yiu Yung, MBBS(HK) FHKCP FHKAM Department of Medicine and Geriatrics (Medicine) United Christian Hospital, Senior Medical Officer 130 Hip Wo Street, Kwun Tong, Dr. Wah-shing Leung, MBChB(CUHK) MRCP(UK) Kowloon, Hong Kong Medical Officer J HK Geriatr Soc 1999;9:29 - 32 Received in revised form on 29 June 1998 Address correspondence to: Dr. CY Yung Summary on level ground and he was home bound, requiring We report a 69-year-old patient presenting with assistance in his activities of daily living. Positive chronic productive cough, progressive dyspnoea, physical findings included diffuse wheezes and airflow obstruction and respiratory failure. He was crackles over the chest. He sought treatment in mislabeled as having chronic obstructive pulmonary various places before seeing us and had been disease (COPD) in the past. Review of his clinical labeled as having COPD, chronic bronchitis and and radiological features finally led to a diagnosis congestive heart failure in the past, and treated as of diffuse panbronchiolitis (DPB). He responded such without improvement. dramatically to long-term low dose erythromycin. The Initial investigations showed a normal blood clinical, radiological and pathological features of the picture and differential counts, biochemistry, renal condition are reviewed. It is important not to miss and liver profiles. Chest radiographs showed diffuse the diagnosis of DPB as it is a potentially treatable micronodules of 2 to 3 mm diameter mainly located condition. -

Immunomodulatory Effects of Azithromycin Revisited: Potential Applications to COVID-19

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Pharmaceutical Sciences Faculty Publications Pharmaceutical Sciences 2-12-2021 Immunomodulatory Effects of Azithromycin Revisited: Potential Applications to COVID-19 Vincent J. Venditto University of Kentucky, [email protected] Dalia Haydar St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Ahmed K. Abdel-Latif University of Kentucky, [email protected] John C. Gensel University of Kentucky, [email protected] See next page for additional authors Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/ps_facpub Part of the Medical Immunology Commons, and the Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences Commons Immunomodulatory Effects of Azithromycin Revisited: Potential Applications to COVID-19 Digital Object Identifier (DOI) https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.574425 Notes/Citation Information Published in Frontiers in Immunology, v. 12, article 574425. © 2021 Venditto, Haydar, Abdel-Latif, Gensel, Anstead, Pitts, Creameans, Kopper, Peng and Feola This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms. Authors Vincent J. Venditto, Dalia Haydar, Ahmed K. Abdel-Latif, John C. Gensel, Michael I. Anstead, Michelle G. Pitts, Jarrod W. Creameans, Timothy J. Kopper, Chi Peng, and David J. -

Middle Airway Obstructiondit May Be Happening Under Our Noses Philip G Bardin,1 Sebastian L Johnston,2 Garun Hamilton1

Thorax Online First, published on July 19, 2012 as 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202221 Chest clinic OPINION Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202221 on 19 July 2012. Downloaded from Middle airway obstructiondit may be happening under our noses Philip G Bardin,1 Sebastian L Johnston,2 Garun Hamilton1 < Additional materials are ABSTRACT for this conceptual error to be refuted.2 The virus is published online only. To view Background Lower airway obstruction has evolved to now understood to spread from nose to lung, and these files please visit the denote pathologies associated with diseases of the lung, appropriate recognition of the close association journal online (http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/ whereas, conditions proximal to the lung embody upper between upper and lower airway pathologies has thoraxjnl-2012-202221/content/ airway obstruction. This approach has disconnected had positive outcomes. An example is novel strat- early/recent). diseases of the larynx and trachea from the lung, and egies that may not be able to prevent colds, but 1Lung and Sleep Medicine, removed the ‘middle airway’ from the interest and that could ameliorate virus asthma exacerbations Monash University and Hospital involvement of respiratory physicians and scientists. through the use of inhaled interferon.3 and Monash Institute of Medical However, recent studies have indicated that dysfunction Accumulating evidence suggests that the middle Research (MIMR), Melbourne, of this anatomical region may be a key component of Australia airway plays a key role in airway obstruction either 2Respiratory Medicine, Imperial overall airway obstruction, either independently or in independently or with coexisting lung disease. -

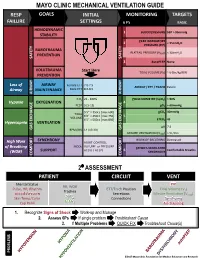

Mechanical Ventilation Guide

MAYO CLINIC MECHANICAL VENTILATION GUIDE RESP GOALS INITIAL MONITORING TARGETS FAILURE SETTINGS 6 P’s BASIC HEMODYNAMIC 1 BLOOD PRESSURE SBP > 90mmHg STABILITY PEAK INSPIRATORY 2 < 35cmH O PRESSURE (PIP) 2 BAROTRAUMA PLATEAU PRESSURE (P ) < 30cmH O PREVENTION PLAT 2 SAFETY SAFETY 3 AutoPEEP None VOLUTRAUMA Start Here TIDAL VOLUME (V ) ~ 6-8cc/kg IBW PREVENTION T Loss of AIRWAY Female ETT 7.0-7.5 AIRWAY / ETT / TRACH Patent Airway MAINTENANCE Male ETT 8.0-8.5 AIRWAY AIRWAY FiO2 21 - 100% PULSE OXIMETRY (SpO2) > 90% Hypoxia OXYGENATION 4 PEEP 5 [5-15] pO2 > 60mmHg 5’5” = 350cc [max 600] pCO2 40mmHg TIDAL 6’0” = 450cc [max 750] 5 VOLUME 6’5” = 500cc [max 850] ETCO2 45 Hypercapnia VENTILATION pH 7.4 GAS GAS EXCHANGE BPM (RR) 14 [10-30] GAS EXCHANGE MINUTE VENTILATION (VMIN) > 5L/min SYNCHRONY WORK OF BREATHING Decreased High Work ASSIST CONTROL MODE VOLUME or PRESSURE of Breathing PATIENT-VENTILATOR AC (V) / AC (P) 6 Comfortable Breaths (WOB) SUPPORT SYNCHRONY COMFORT COMFORT 2⁰ ASSESSMENT PATIENT CIRCUIT VENT Mental Status PIP RR, WOB Pulse, HR, Rhythm ETT/Trach Position Tidal Volume (V ) Trachea T Blood Pressure Secretions Minute Ventilation (V ) SpO MIN Skin Temp/Color 2 Connections Synchrony ETCO Cap Refill 2 Air-Trapping 1. Recognize Signs of Shock Work-up and Manage 2. Assess 6Ps If single problem Troubleshoot Cause 3. If Multiple Problems QUICK FIX Troubleshoot Cause(s) PROBLEMS ©2017 Mayo Clinic Foundation for Medical Education and Research CAUSES QUICK FIX MANAGEMENT Bleeding Hemostasis, Transfuse, Treat cause, Temperature control HYPOVOLEMIA Dehydration Fluid Resuscitation (End points = hypoxia, ↑StO2, ↓PVI) 3rd Spacing Treat cause, Beware of hypoxia (3rd spacing in lungs) Pneumothorax Needle D, Chest tube Abdominal Compartment Syndrome FLUID Treat Cause, Paralyze, Surgery (Open Abdomen) OBSTRUCTED BLOOD RETURN Air-Trapping (AutoPEEP) (if not hypoxic) Pop off vent & SEE SEPARATE CHART PEEP Reduce PEEP Cardiac Tamponade Pericardiocentesis, Drain. -

Radioaerosol Lung Scanning in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and Related Disorders

88 XAOIOOIOO Radioaerosol Lung Scanning in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and Related Disorders Yong Whee Bahk, M.D. and Soo Kyo Chung, M.D. Introduction As a coordinated research project of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) a multicentre joint study on radioaerosol lung scan using the BARC nebulizer [1] has prospectively been carried out during 1988-1992 with the participation of 10 member countries in Asia [Bangladesh, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Pakistan, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand]. The study was designed so that it would primarily cover chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and the other related and common pulmonary diseases. The study also included normal controls and asymptomatic smokers. The purposes of this presentation are three fold: firstly, to document the useful- ness of the nebulizer and the validity of user's protocol in imaging COPD and other lung diseases; secondly, to discuss scan features of the individual COPD and other disorders studied and thirdly, to correlate scan alterations with radiographie find- ings. Before proceeding with a systematic analysis of aerosol scan patterns in the disease groups, we documented normal pattern. The next step was the assessment of scan features in those who had been smoking for more than several years but had no symptoms or signs referable to airways. The lung diseases we analyzed included COPD [emphysema, chronic bronchitis, asthma and bronchiectasis], bron- chial obstruction, compensatory overinflation and other common lung diseases such as lobar pneumonia, tuberculosis, interstitial fibrosis, diffuse panbronchiolitis, lung edema and primary and metastatic lung cancers. Lung embolism, inhalation burns and glue-sniffer's lung are seperately discussed by Dr. -

A Case of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Treated with Clarithromycin

CASE REPORT East J Med 21(1): 39-41, 2016 A case of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis treated with clarithromycin Masashi Ohe1,* and Satoshi Hashino2 1Department of General Medicine, Hokkaido Social Insurance Hospital, Sapporo, Japan 2Hokkaido University, Health Care Center, Sapporo, Japan ABSTRACT We report a case of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) treated successfully using clarithromycin (CAM). A 64-year-old male patient suffering from IPF which had been diagnosed at 59 years old, presented with slowly progressive dyspnea. Until this time, his condition had been almost stable. He was diagnosed with exacerbation of IPF, based on exacerbation of lung ausculation, O2 saturation by pulse oxymetry, Krebs von den Lungen 6 levels and chest computed tomography findings of reticular opacities. He was successfully treated using CAM in expectation of its anti-inflammatory effects. This case shows that treatment using CAM may be effective in some cases of IPF. Key Words: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, Clarithromycin Introduction protein (CRP), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and Krebs von den Lungen (KL)-6 levels which are Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is progressive known to indicate the activity of interstitial and fatal lung disease. Recent study suggested pneumonia (4), and CT findings remained almost pirfenidone might be effective in slowing the unchanged, he did not receive any treatment. Six decline of lung function on early-stage IPF months before this episode of dyspnea, SpO2 persons (1). However, despite multiple recent indicated 94% in room air at rest. CRP, LDH, and clinical trials, no definite therapy other than lung KL-6 levels were 0.2 mg/dL (normal range <0.3 transplantation is known to alter survival (2). -

Klebsiella Pneumoniae in Diffuse Panbronchiolitis

※ 附來的圖四解析度和原來一樣哦 , 應該不是原始檔案 , 如沒有原圖印刷就是字不漂亮 DOI:10.6314/JIMT.202012_31(6).07 內科學誌 2020:31:432-436 Klebsiella Pneumoniae in Diffuse Panbronchiolitis Hwee-Kheng Lim1, Sho-Ting Hung2, and Shih-Yi Lee3,4 1Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, 2Department of Radiology, 3Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Taitung MacKay Memorial Hospital, Taitung, Taiwan; 4MacKay Medicine, Nursing & Management College Abstract Diffuse panbronchiolitis (DPB) is a chronic, idiopathic, rare but lethal inflammatory airway disease resulting in distal airway dilation, obstructive lung disease, hypoxemia, and increased in the susceptibility of bacteria colonization. The case reports that a patient with destructive lung gets pneumonia by Klebsiella pneu- moniae cured by bactericidal antibiotics, but K. pneumoniae in the airway is eradicated with erythromycin, which therefore highlights not only the importance to the testing for DPB in suspicious patients, but also the therapeutic strategies in managing DPB with K. pneumoniae in the airways. (J Intern Med Taiwan 2020; 31: 432-436) Key Words: Klebsiella pneumoniae, Panbronchiolitis Introduction the survival of the patients with DPB in the literature also reduces P. aeruginosa isolated from the sputum. Diffuse panbronchiolitis (DPB) is a chronic P. aeruginosa in sputum appears to accelerate the inflammatory disease of the airways, and the diag- destructive process3. However, the role of Klebsiella nosis depends on the clinical symptoms, physical pneumoniae in DPB has never been reported. We signs, typical chest radiographic findings, low FEV1 present a patient with DPB and K. pneumoniae iso- (< 70%) in pulmonary function tests, low arterial lated from sputum, refractory to ampicillin/sulbac- partial pressure (< 80 mmHg), elevated cold hem- tam, but eradicated by erythromycin. -

Exercise-Induced Laryngeal Obstruction

American Thoracic Society PATIENT EDUCATION | INFORMATION SERIES Exercise-induced Laryngeal Obstruction Exercise-induced laryngeal obstruction (EILO) is a breathing problem that affects people during exercise. EILO is defined by inappropriate narrowing of the upper airway at the level of the vocal cords (glottis) and/or supraglottis (above the vocal cords). This can make it hard to get air into your lungs during exercise and cause a noisy breathing that can be frightening. EILO has also been called vocal cord dysfunction (VCD) or paradoxical vocal fold motion (PVFM). Most people with EILO only have symptoms when they Common signs and symptoms of EILO exercise, those some people may have the problem at During (or immediately after) high-intensity exercise, other times as well. (See ATS Patient Information Series with EILO you may experience: fact sheet ‘Inducible Laryngeal Obstruction/Vocal Cord ■■ Profound shortness of breath or breathlessness Dysfunction’) ■■ Noisy breathing, particularly when breathing in Where are the vocal cords and what do they do? (stridor, gasping, raspy sounds, or “wheezing”) Your vocal cords are located in your upper airway or ■■ A feeling of choking or suffocation that can be scary larynx. Your supraglottic structures (including your ■■ CLIP AND COPY AND CLIP Feeling like there is a lump in the throat arytenoid cartilages and epiglottis) are located above the ■■ Throat or chest tightness vocal cords and are part of your larynx. The larynx is often called the voice box and is deep in your throat. When These symptoms often come on suddenly during you speak, the vocal cords vibrate as you breathe out, exercise, and are typically quite noticeable or concerning to people around you as well. -

RADS and the Bhopal Disaster

Eur Respir J, 1996, 9, 1973–1976 Copyright ERS Journals Ltd 1996 DOI: 10.1183/09031936.96.09101973 European Respiratory Journal Printed in UK - all rights reserved ISSN 0903 - 1936 EDITORIAL Late consequences of accidental exposure to inhaled irritants: RADS and the Bhopal disaster B. Nemery Pulmonary physicians occasionally have to evaluate tims of civil disasters, such as explosions, fires or major patients some time after an acute inhalation injury and chemical spills, which involved a few tens of subjects to make a judgement about the existence of residual at most. Although these studies provided evidence of lung lesions, the possible causal relationship of such persistent obstructive defects in some subjects, until the lesions with the accident, and their prognosis. This has early 1980s, the prevailing opinion, judging from two been a difficult and often contentious issue, ever since leading textbooks [2, 3], was that "complete recovery" former servicemen who had been gassed in the first was the rule for most individuals surviving acute expo- world war, claimed compensation for late respiratory sure. As late as 1987, an extensive review article [4] effects. Thus, in a review and opinion article published considered that "the chronic effects of acute exposures 35 yrs after the large scale use of war gases [1], it is to toxic inhalants have not been clearly characterized". stated that "the physical impact on men exposed to these Although this is still true to a large extent, significant substances has been a source of interest to, and spe- progress has been made over the past 10 yrs, mainly as culation by, the medical profession, and amidst the a result of the "discovery" of the reactive airways dys- emotional and sentimental miasma which may cloud function syndrome (RADS).