Globalizing Nature on the Shakespearean Stage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Front.Chp:Corel VENTURA

Book Reviews 145 circumstances, as in his dealings with Polonius, and Rosencrantz and Guild- enstern. Did he not think he was killing the King when he killed Polonius? That too was a chance opportunity. Perhaps Hirsh becomes rather too confined by a rigorous logical analysis, and a literal reading of the texts he deals with. He tends to brush aside all alternatives with an appeal to a logical certainty that does not really exist. A dramatist like Shakespeare is always interested in the dramatic potential of the moment, and may not always be thinking in terms of plot. (But as I suggest above, the textual evidence from plot is ambiguous in the scene.) Perhaps the sentimentalisation of Hamlet’s character (which the author rightly dwells on) is the cause for so many unlikely post-renaissance interpretations of this celebrated soliloquy. But logical rigour can only take us so far, and Hamlet, unlike Brutus, for example, does not think in logical, but emotional terms. ‘How all occasions do inform against me / And spur my dull revenge’ he remarks. Anthony J. Gilbert Claire Jowitt. Voyage Drama and Gender Politics 1589–1642: Real and Imagined Worlds. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003. Pp 256. For Claire Jowitt, Lecturer in Renaissance literature at University of Wales Aberystwyth, travel drama depicts the exotic and the foreign, but also reveals anxieties about the local and the domestic. In this her first book, Jowitt, using largely new historicist methodology, approaches early modern travel plays as allegories engaged with a discourse of colonialism, and looks in particular for ways in which they depict English concerns about gender, leadership, and national identity. -

James Ivory in France

James Ivory in France James Ivory is seated next to the large desk of the late Ismail Merchant in their Manhattan office overlooking 57th Street and the Hearst building. On the wall hangs a large poster of Merchant’s book Paris: Filming and Feasting in France. It is a reminder of the seven films Merchant-Ivory Productions made in France, a source of inspiration for over 50 years. ....................................................Greta Scacchi and Nick Nolte in Jefferson in Paris © Seth Rubin When did you go to Paris for the first time? Jhabvala was reading. I had always been interested in Paris in James Ivory: It was in 1950, and I was 22. I the 1920’s, and I liked the story very much. Not only was it my had taken the boat train from Victoria Station first French film, but it was also my first feature in which I in London, and then we went to Cherbourg, thought there was a true overall harmony and an artistic then on the train again. We arrived at Gare du balance within the film itself of the acting, writing, Nord. There were very tall, late 19th-century photography, décor, and music. apartment buildings which I remember to this day, lining the track, which say to every And it brought you an award? traveler: Here is Paris! JI: It was Isabelle Adjani’s first English role, and she received for this film –and the movie Possession– the Best Actress You were following some college classmates Award at the Cannes Film Festival the following year. traveling to France? JI: I did not want to be left behind. -

The Cultural and Ideological Significance of Representations of Boudica During the Reigns of Elizabeth I and James I

EXETER UNIVERSITY AND UNIVERSITÉ D’ORLÉANS The Cultural and Ideological Significance Of Representations of Boudica During the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I. Submitted by Samantha FRENEE-HUTCHINS to the universities of Exeter and Orléans as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, June 2009. This thesis is available for library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgment. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. ..................................... (signature) 2 Abstract in English: This study follows the trail of Boudica from her rediscovery in Classical texts by the humanist scholars of the fifteenth century to her didactic and nationalist representations by Italian, English, Welsh and Scottish historians such as Polydore Virgil, Hector Boece, Humphrey Llwyd, Raphael Holinshed, John Stow, William Camden, John Speed and Edmund Bolton. In the literary domain her story was appropriated under Elizabeth I and James I by poets and playwrights who included James Aske, Edmund Spenser, Ben Jonson, William Shakespeare, A. Gent and John Fletcher. As a political, religious and military figure in the middle of the first century AD this Celtic and regional queen of Norfolk is placed at the beginning of British history. In a gesture of revenge and despair she had united a great number of British tribes and opposed the Roman Empire in a tragic effort to obtain liberty for her family and her people. -

The Official Organ of the B.Bc

Radio Times, August 21st, 1925. GREAT BROADCAST SEASON APPROACHES. oJ Ri se oea i = — T . aa oh, att THE OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE B.BC — SS ——er ngistered cat the _Vol. §i_No, 100. GEO. a oo See per, _EVERY FRIDAY. Two Pence. OFFICIAL. Broadcasting Smiles! — PROGRAMMES By GEORGE GROSSMITH. for the week commencing EOPLEare pining for wireless humour. the correct mo- SUNDAY, August 23rd. Unfortunately, there is a regrettable ments ! If might = —— se dearth of radio comedians, not only if} be thought that MAIN STATIONS. this country, but also in America. Several a small audience LONDON, CARDIFF, ABERDEEN, GLAS- famous comedians have tried their hand in the ‘broad- casting studio GOW, BIRMINGHAM, MANCHESTER, at making listeners Laugh, but have acted as if they WET on the stare, lorpetting would help a BOURNEMOUTH, NEWCASTLE, BELFAST. that the ear ‘of listeners is not comple- comedian. But mented by the eye, a5 it is in a theatre. this has been HIGH-POWER STATION. Many mirth-makers on the stage rely tried and not (Daventry.) upon facial expression for fully half of their found of great success, Theyare likely to fail when they assistance, RELAY STATIONS, broaceast. ‘* = SHEFFIELD, PLYMOUTH, EDINBURGH, a i w i (an humour LIVERPOOL, LEEDS—BRADFORD, Few people appreciate the importance becommunicated Mr. GEORGE GROSSMITH. HULL, NOTTINGHAM, STOKE-ON- of the audience to a comedian. Correct by the ear alone ? TRENT, DUNDEE, SWANSEA. timing of the remarks. in a joke is often Many comedians reply with an emphatic an essential feature, and the speaker takes ‘No.” That cold-blooded microphone, SPECIAL CONTENTS. -

Sommario Rassegna Stampa

Sommario Rassegna Stampa Pagina Testata Data Titolo Pag. Rubrica Anica Web Classtravel.it 04/02/2021 AQUA FILM FESTIVAL 3 Cinecitta.com 03/02/2021 PAOLO MANERA: "LE SERIE TV NEL NOSTRO DNA" 6 Mediabiz.de 03/02/2021 BIRGIT OBERKOFLER: "BLICK NACH VORNE RICHTEN" 10 Viviroma.tv 03/02/2021 AL VIA LA VI EDIZIONE DEL FILMING ITALY LOS ANGELES 18/21 12 MARZO 2021 Rubrica Cinema 26 Avvenire 04/02/2021 FEDS, FILM SULLA "VITA NUOVA" 16 1 Corriere della Sera 04/02/2021 STORICO AI GOLDEN GLOBE TRIS DI REGISTE IN LIZZA (G.Sarcina) 17 23 Il Fatto Quotidiano 04/02/2021 "RUMORE BIANCO" AL CINEMA 20 2 Il Foglio 04/02/2021 NETFLIX FA MAN BASSA DI NOMINATION AI GOLDEN GLOBE NELLA 21 SEZIONE CINEMA 2 Il Foglio 04/02/2021 RIALZARE I SIPARI 22 23 Il Mattino 04/02/2021 Int. a A.Truppo: "CRAZY FOR FOOTBALL", TRUPPO RACCONTA I 23 "MATTI PER IL CALCIO" (A.Farro) 24 Il Messaggero 04/02/2021 GOLDEN GLOBE, NO ALLA LOREN SI' A PAUSINI E BOSEMAN (G.Satta) 24 24 Il Messaggero 04/02/2021 MORTA NONI CORBUCCI, COSTUMISTA E VEDOVA DEL REGISTA 25 SERGIO 33 Tuttomilano (La Repubblica) 04/02/2021 CULTURA- LA PRIMA SALA-CINEMA PER BAMBINI 26 Rubrica Audiovisivo & Multimedia 65 Il Messaggero - Cronaca di Roma 04/02/2021 NETFLIX TROVA CASA A ROMA: LA SEDE A VILLINO RATTAZZI NEL 27 CUORE DELLA DOLCE VITA (G.Satta) 23 Avvenire 04/02/2021 A PICCO I RICAVI DEI MEDIA VA BENE L'ON-DEMAND, MALE LA 28 PUBBLICITA' LO STREAMING BATTE LA TV 31 Corriere della Sera 04/02/2021 IL LOCKDOWN PREMIA NETFLIX PUBBLICITA', IN NOVEMBRE LA7 29 CRESCE DELL'8,8% (S.Bocconi) 40 Corriere della Sera 04/02/2021 Int. -

English 252: Theatre in England 2006-2007 * [Optional Events

English 252: Theatre in England 2006-2007 * [Optional events — seen by some] Wednesday December 27 *2:30 p.m. Guys and Dolls (1950). Dir. Michael Grandage. Music & lyrics by Frank Loesser, Book by Jo Swerling and Abe Burrows. Based on a story and characters of Damon Runyon. Designer: Christopher Oram. Choreographer: Rob Ashford. Cast: Alex Ferns (Nathan Detroit), Samantha Janus (Miss Adelaide), Amy Nuttal (Sarah Brown), Norman Bowman (Sky Masterson), Steve Elias (Nicely Nicely Johnson), Nick Cavaliere (Big Julie), John Conroy (Arvide Abernathy), Gaye Brown (General Cartwright), Jo Servi (Lt. Brannigan), Sebastien Torkia (Benny Southstreet), Andrew Playfoot (Rusty Charlie/ Joey Biltmore), Denise Pitter (Agatha), Richard Costello (Calvin/The Greek), Keisha Atwell (Martha/Waitress), Robbie Scotcher (Harry the Horse), Dominic Watson (Angie the Ox/MC), Matt Flint (Society Max), Spencer Stafford (Brandy Bottle Bates), Darren Carnall (Scranton Slim), Taylor James (Liverlips Louis/Havana Boy), Louise Albright (Hot Box Girl Mary-Lou Albright), Louise Bearman (Hot Box Girl Mimi), Anna Woodside (Hot Box Girl Tallulha Bloom), Verity Bentham (Hotbox Girl Dolly Devine), Ashley Hale (Hotbox Girl Cutie Singleton/Havana Girl), Claire Taylor (Hot Box Girl Ruby Simmons). Dance Captain: Darren Carnall. Swing: Kate Alexander, Christopher Bennett, Vivien Carter, Rory Locke, Wayne Fitzsimmons. Thursday December 28 *2:30 p.m. George Gershwin. Porgy and Bess (1935). Lyrics by DuBose Heyward and Ira Gershwin. Book by Dubose and Dorothy Heyward. Dir. Trevor Nunn. Design by John Gunter. New Orchestrations by Gareth Valentine. Choreography by Kate Champion. Lighting by David Hersey. Costumes by Sue Blane. Cast: Clarke Peters (Porgy), Nicola Hughes (Bess), Cornell S. John (Crown), Dawn Hope (Serena), O-T Fagbenie (Sporting Life), Melanie E. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Tackling Challenging Issues in Shakespeare for Young Audiences

Shrews, Moneylenders, Soldiers, and Moors: Tackling Challenging Issues in Shakespeare for Young Audiences DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Elizabeth Harelik, M.A. Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Professor Lesley Ferris, Adviser Professor Jennifer Schlueter Professor Shilarna Stokes Professor Robin Post Copyright by Elizabeth Harelik 2016 Abstract Shakespeare’s plays are often a staple of the secondary school curriculum, and, more and more, theatre artists and educators are introducing young people to his works through performance. While these performances offer an engaging way for students to access these complex texts, they also often bring up topics and themes that might be challenging to discuss with young people. To give just a few examples, The Taming of the Shrew contains blatant sexism and gender violence; The Merchant of Venice features a multitude of anti-Semitic slurs; Othello shows characters displaying overtly racist attitudes towards its title character; and Henry V has several scenes of wartime violence. These themes are important, timely, and crucial to discuss with young people, but how can directors, actors, and teachers use Shakespeare’s work as a springboard to begin these conversations? In this research project, I explore twenty-first century productions of the four plays mentioned above. All of the productions studied were done in the United States by professional or university companies, either for young audiences or with young people as performers. I look at the various ways that practitioners have adapted these plays, from abridgments that retain basic plot points but reduce running time, to versions incorporating significant audience participation, to reimaginings created by or with student performers. -

Early Birding Book

Early Birding in Dutchess County 1870 - 1950 Before Binoculars to Field Guides by Stan DeOrsey Published on behalf of The Ralph T. Waterman Bird Club, Inc. Poughkeepsie, New York 2016 Copyright © 2016 by Stan DeOrsey All rights reserved First printing July 2016 Digital version June 2018, with minor changes and new pages added at the end. Digital version July 2019, pages added at end. Cover images: Front: - Frank Chapman’s Birds of Eastern North America (1912 ed.) - LS Horton’s post card of his Long-eared Owl photograph (1906). - Rhinebeck Bird Club’s second Year Book with Crosby’s “Birds and Seasons” articles (1916). - Chester Reed’s Bird Guide, Land Birds East of the Rockies (1908 ed.) - 3x binoculars c.1910. Back: 1880 - first bird list for Dutchess County by Winfrid Stearns. 1891 - The Oölogist’s Journal published in Poughkeepsie by Fred Stack. 1900 - specimen tag for Canada Warbler from CC Young collection at Vassar College. 1915 - membership application for Rhinebeck Bird Club. 1921 - Maunsell Crosby’s county bird list from Rhinebeck Bird Club’s last Year Book. 1939 - specimen tag from Vassar Brothers Institute Museum. 1943 - May Census checklist, reading: Raymond Guernsey, Frank L. Gardner, Jr., Ruth Turner & AF [Allen Frost] (James Gardner); May 16, 1943, 3:30am - 9:30pm; Overcast & Cold all day; Thompson Pond, Cruger Island, Mt. Rutson, Vandenburg’s Cove, Poughkeepsie, Lake Walton, Noxon [in LaGrange], Sylvan Lake, Crouse’s Store [in Union Vale], Chestnut Ridge, Brickyard Swamp, Manchester, & Home via Red Oaks Mill. They counted 117 species, James Gardner, Frank’s brother, added 3 more. -

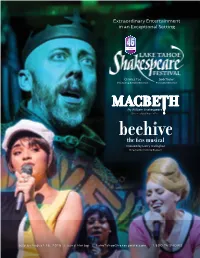

Extraordinary Entertainment in an Exceptional Setting

Extraordinary Entertainment in an Exceptional Setting Charles Fee Bob Taylor Producing Artistic Director Executive Director By William Shakespeare Directed by Charles Fee Created by Larry Gallagher Directed by Victoria Bussert July 6–August 26, 2018 | Sand Harbor | L akeTahoeShakespeare.com | 1.800.74.SHOWS Enriching lives, inspiring new possibilities. At U.S. Bank, we believe art enriches and inspires our community. That’s why we support the visual and performing arts organizations that push our creativity and passion to new levels. When we test the limits of possible, we fi nd more ways to shine. usbank.com/communitypossible U.S. Bank is proud to support the Lake Tahoe Shakespeare Festival. Incline Village Branch 923 Tahoe Blvd. Incline Village, NV 775.831.4780 ©2017 U.S. Bank. Member FDIC. 171120c 8.17 “World’s Most Ethical Companies” and “Ethisphere” names and marks are registered trademarks of Ethisphere LLC. 2018 Board of Directors Patricia Engels, Chair Michael Chamberlain, Vice Chair Atam Lalchandani, Treasurer Mary Ann Peoples, Secretary Wayne Cameron Scott Crawford Katharine Elek Amanda Flangas John Iannucci Vicki Kahn Charles Fee Bob Taylor Nancy Kennedy Producing Artistic Director Executive Director Roberta Klein David Loury Vicki McGowen Dear Friends, Judy Prutzman Welcome to the 46th season of Lake Tahoe Shakespeare Festival, Nevada’s largest professional, non-profit Julie Rauchle theater and provider of educational outreach programming! Forty-six years of Shakespeare at Lake Tahoe D.G. Menchetti, Director Emeritus is a remarkable achievement made possible by the visionary founders and leaders of this company, upon whose shoulders we all stand, and supported by the extraordinary generosity of this community, our board Allen Misher, Director Emeritus of directors, staff, volunteers, and the many artists who have created hundreds of evenings of astonishing Warren Trepp, Honorary Founder entertainment under the stars. -

The Development of the Role of the Actor-Musician in Britain by British Directors Since the 1960’S

1 The Development of the Role of the Actor-Musician in Britain by British Directors Since the 1960’s Francesca Mary Greatorex Theatre and Performance Department Goldsmiths University of London A thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) 2 I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Signed: ……………………………………………. 3 Acknowledgements This thesis could not have been written without the generosity of many individuals who were kind enough to share their knowledge and theatre experience with me. I have spoken with actors, musical directors, set designers, directors, singers, choreographers and actor-musicians and their names and testaments exist within the thesis. I should like to thank Emily Parsons the archivist for the Liverpool Everyman for all her help with my endless requests. I also want to thank Jonathan Petherbridge at the London Bubble for making the archive available to me. A further thank you to Rosamond Castle for all her help. On a sadder note a posthumous thank you to the director Robert Hamlin. He responded to my email request for the information with warmth, humour and above all, great enthusiasm for the project. Also a posthumous thank you to the actor, Robert Demeger who was so very generous with the information regarding the production of Ninagawa’s Hamlet in which he played Polonius. Finally, a big thank you to John Ginman for all his help, patience and advice. 4 The Development of the Role of the Actor-Musician in Britain by British Directors During the Period 1960 to 2000. -

2.2 Final.Indd

Wickedly Devotional Comedy in the York Temptation of Christ1 Christopher Crane United States Naval Academy Make rome belyve, and late me gang! [let me pass!] Who makes here al þis þrang? High you hense, high myght ou hang Right with a roppe. I drede me þat I dwelle to lang [I’m delayed too long] To do a jape. [mischief, joke] (York Plays 22.1-6) Satan opens the York Temptation of Christ2 pageant with these words, employing a complex and subtle rhetorical comedy aimed at moving fi fteenth-century spectators toward lives of greater devotion. With “late me gang!” Satan (“Diabolus” in the text) achieves more in these lines than just making a scene; he draws his audience members into the action. Medieval staging in York likely had Satan approach the pageant wagon stage through the audience, addressing them as he enters. As spectators respond, perhaps stepping aside, smiling, or even egging him on, they both submit to and celebrate him. However, the central action of this pageant is Christ’s successful resistance to the devil’s efforts to entice him to sin.3 Theologically and thematically, this victory parallels the pageant of Adam and Eve’s temptation earlier in the cycle4 and establishes Christ’s qualifi cation to redeem the fall of mankind with his death, which follows in the series of passion pageants that follow this scene. If the purpose of this pageant is to illustrate Christ’s victory, why does it open with this entertaining portrayal of Satan? Why not portray Jesus in prayer or meditating on the Scriptures he will use to resist Satan’s tactics? Can the pageant provide an orthodox message about the devil after endowing him with such charisma? The exemplary and biblical nature of the mystery plays in general (whether humorous or not) gives them a homiletic quality that frequently invites the audience to 29 30 Christopher Crane participate vicariously in the enacted stories and to appropriate the lessons of Scripture.