Taping Ireland &Ndash

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inside: Shrimp Cake Topped with a Lemon Aioli, Caulilini and Roasted Tomato Medley and Pommes Fondant

Epicureans March 2019 Upcoming The President’s Message Hello to all my fellow members and enthusiasts. We had an amazing meeting this February at The Draft Room Meetings & located in the New Labatt Brew House. A five course pairing that not only showcased the foods of the Buffalo Events: region, but also highlighted the versatility and depth of flavors craft beers offer the pallet. Thank you to our keynote speaker William Keith, Director of Project management of BHS Foodservice Solutions for his colloquium. Also ACF of Greater Buffalo a large Thank-You to the GM Brian Tierney, Executive Chef Ron Kubiak, and Senior Bar Manager James Czora all with Labatt Brew house for the amazing service and spot on pairing of delicious foods and beer. My favorite NEXT SOCIAL was the soft doughy pretzel with a perfect, thick crust accompanied by a whole grain mustard, a perfect culinary MEETING amalgamation! Well it’s almost spring, I think I can feel it. Can’t wait to get outside at the Beer Garden located on the Labatt house property. Even though it feels like it’ll never get here thank goodness for fun events and GREAT FOOD!! This region is not only known for spicy wings, beef on weck and sponge candy, but as a Buffalo local you can choose from an arsenal of delicious restaurants any day of the week. To satisfy what craves you, there are a gamut of food trends that leave the taste buds dripping Buffalo never ceases to amaze. From late night foods, food trucks, micro BHS FOODSERVICE beer emporiums, Thai, Polish, Lebanese, Indian, on and on and on. -

CHAPTER-2 Charcutierie Introduction: Charcuterie (From Either the French Chair Cuite = Cooked Meat, Or the French Cuiseur De

CHAPTER-2 Charcutierie Introduction: Charcuterie (from either the French chair cuite = cooked meat, or the French cuiseur de chair = cook of meat) is the branch of cooking devoted to prepared meat products such as sausage primarily from pork. The practice goes back to ancient times and can involve the chemical preservation of meats; it is also a means of using up various meat scraps. Hams, for instance, whether smoked, air-cured, salted, or treated by chemical means, are examples of charcuterie. The French word for a person who prepares charcuterie is charcutier , and that is generally translated into English as "pork butcher." This has led to the mistaken belief that charcuterie can only involve pork. The word refers to the products, particularly (but not limited to) pork specialties such as pâtés, roulades, galantines, crépinettes, etc., which are made and sold in a delicatessen-style shop, also called a charcuterie." SAUSAGE A simple definition of sausage would be ‘the coarse or finely comminuted (Comminuted means diced, ground, chopped, emulsified or otherwise reduced to minute particles by mechanical means) meat product prepared from one or more kind of meat or meat by-products, containing various amounts of water, usually seasoned and frequently cured .’ A sausage is a food usually made from ground meat , often pork , beef or veal , along with salt, spices and other flavouring and preserving agents filed into a casing traditionally made from intestine , but sometimes synthetic. Sausage making is a traditional food preservation technique. Sausages may be preserved by curing , drying (often in association with fermentation or culturing, which can contribute to preservation), smoking or freezing. -

St. Patrick Was Not Irish. He Was Born Maewyn Succat in Britain

St. Patrick Was Not Irish. He Was Born Maewyn Succat In Britain St. Patrick’s Day kicks off a worldwide celebration that is also known as the Feast of St. Patrick. On March 17th, many will wear green in honor of the Irish and decorate with shamrocks. In fact, the wearing of the green is a tradition that dates back to a story written about St. Patrick in 1726. St. Patrick (c. AD 385–461) was known to use the shamrock to illustrate the Holy Trinity and to have worn green clothing. They’ll revel in the Irish heritage and eat traditional Irish fare, too. In the United States, St. Patrick’s Day has been celebrated since before the country was formed. While the holiday has been a bit more of a rowdy one, with green beer, parades, and talk of leprechauns, in Ireland, it the day is more of a solemn event. It wasn’t until broadcasts of the events in the United States were aired in Ireland some of the Yankee ways spread across the pond. One tradition that is an Irish-American tradition not common to Ireland is corned beef and cabbage. In 2010, the average Irish person aged 15+ drank 11.9 litres (3 gallons) of pure alcohol, according to provisional data. That’s the equivalent of about 44 bottles of vodka, 470 pints or 124 bottles of wine. There is a famous Irish dessert known as Drisheen, a surprisingly delicious black pudding. The leprechaun, famous to Ireland, is said to grant wishes to those who can catch them. -

Socialist Fight No.08

Socialist Fight Issue No. 8 Winter 2011/2012 Price: Concessions: 50p, Waged: £2.00 €3.00 Euro zone crisis—Morning Star warns of the ‘germanisation’ of Europe! Page 2 Contents Page 2: Editorial: Euro zone crisis—Morning Star warns of the ‘germanisation’ of Europe! Page 3: GRL Pages: London Busworkers under attack – Remove Unite RIO Wayne King By Gerry Downing. Page 4: GRL “We are not dogs” petition and campaign, URGENT- PINHEIRINHO UNDER ATTACK Page 5: Unite behind the sparks, Site Worker Report, Off with their heads (of agreement)! Page 7: The 2011 Summer Riots: Engels, the English working class and the difference from the thirties By Celia Ralph. Page 8: Leon Trotsky – As he should be known By Ret Marut. Page 9: A meeting with a Friend of Israel By Therese Peters Page 10: Two Salient points on the Libyan up-rising – in defence of vulnerable Libyans By Ella Downing. Page 10: International relations established with comrades in Argentina and Sri Lanka. Page 11: Defence of the Imperialist Nation State is a reactionary trap for the working class By AJ Byrne. Page 13: The framing of Michael McKevitt By Michael Holden. Page 14: Defend Civil Liberties: Political Status for Irish Republi- can Prisoners, — IRPSG. Page 15: Bloody Sunday March for Justice. Page 16: Letter to The Kilkenny People by Charlie Walsh. Page 17: Dale Farm Irish Travellers (Pavees) fight on By Tony Fox. Page 18: We are not the 99% By Ella Downing. Page 19: Engels "On Authority" By the Liga Comunista. Page 21: On consensus: from Murray Bookchin’s "What is Com- munalism? The Democratic Dimensions of Anarchism". -

Chapter 18 : Sausage the Casing

CHAPTER 18 : SAUSAGE Sausage is any meat that has been comminuted and seasoned. Comminuted means diced, ground, chopped, emulsified or otherwise reduced to minute particles by mechanical means. A simple definition of sausage would be ‘the coarse or finely comminuted meat product prepared from one or more kind of meat or meat by-products, containing various amounts of water, usually seasoned and frequently cured .’ In simplest terms, sausage is ground meat that has been salted for preservation and seasoned to taste. Sausage is one of the oldest forms of charcuterie, and is made almost all over the world in some form or the other. Many sausage recipes and concepts have brought fame to cities and their people. Frankfurters from Frankfurt in Germany, Weiner from Vienna in Austria and Bologna from the town of Bologna in Italy. are all very famous. There are over 1200 varieties world wide Sausage consists of two parts: - the casing - the filling THE CASING Casings are of vital importance in sausage making. Their primary function is that of a holder for the meat mixture. They also have a major effect on the mouth feel (if edible) and appearance. The variety of casings available is broad. These include: natural, collagen, fibrous cellulose and protein lined fibrous cellulose. Some casings are edible and are meant to be eaten with the sausage. Other casings are non edible and are peeled away before eating. 1 NATURAL CASINGS: These are made from the intestines of animals such as hogs, pigs, wild boar, cattle and sheep. The intestine is a very long organ and is ideal for a casing of the sausage. -

W.T. Cosgrave Papers P285 Ucd Archives

W.T. COSGRAVE PAPERS P285 UCD ARCHIVES [email protected] www.ucd.ie/archives T + 353 1 716 7555 F + 353 1 716 1146 © 2015 University College Dublin. All Rights Reserved ii CONTENTS CONTEXT Biographical History iv Archival History vi CONTENT AND STRUCTURE Scope and Content vii System of Arrangement viii CONDITIONS OF ACCESS AND USE Access ix Language ix Finding Aid ix DESCRIPTION CONTROL Archivist’s Note ix iii CONTEXT Biographical history William Thomas Cosgrave was born on 6 June 1880 at 174 James’ Street, Dublin. He attended the Christian Brothers School in Marino, and later worked in the family business, a grocers and licensed premises. His first brush with politics came in 1905 when, with his brother Phil and uncle P.J., he attended the first Sinn Féin convention in 1905. Serving as a Sinn Féin councillor on Dublin Corporation from 1909 until 1922, he joined the Irish Volunteers in 1913, although he never joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood. During the Easter 1916 Rising, Cosgrave served under Eamonn Ceannt at the South Dublin Union. His was not a minor role, and after the Rising he was sentenced to death. This was later commuted to penal servitude for life, and he was transported to Frongoch in Wales along with many other rebels. As public opinion began to favour the rebels, Cosgrave stood for election in the 1917 Kilkenny city by-election, and won despite being imprisoned. This was followed by another win the following year in Kilkenny North. Cosgrave took his seat in the First Dáil on his release from prison in 1919. -

Downloaded 2021-09-26T08:20:53Z

Provided by the author(s) and University College Dublin Library in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Analysing the development of bipartisanship in the Dáil : the interaction of Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil party politics on the Irish government policy on Northern Ireland Authors(s) McDermott, Susan Publication date 2009 Conference details Prepared for presentation at the annual meeting of the Specialist Group on Britishand Comparative Territorial Politics of the Political Studies Association of the UnitedKingdom, University of Oxford, 7-8 January 2010 Series IBIS Discussion Papers : Breaking the Patterns of Conflict Series; 7 Publisher University College Dublin. Institute for British-Irish Studies Item record/more information http://hdl.handle.net/10197/2410 Publisher's statement Preliminary draft, not for citation Downloaded 2021-09-26T08:20:53Z The UCD community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters! (@ucd_oa) © Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. ANALYSING THE DEVELOPMENT OF BIPARTISANSHIP IN THE DÁIL: THE INTERACTION OF FINE GAEL AND FIANNA FÁIL PARTY POLITICS ON THE IRISH GOVERNMENT POLICY ON NORTHERN IRELAND Susan McDermott IBIS Discussion Paper No. 7 ANALYSING THE DEVELOPMENT OF BIPARTISANSHIP IN THE DÁIL: THE INTERACTION OF FINE GAEL AND FIANNA FÁIL PARTY POLITICS ON THE IRISH GOVERNMENT POLICY ON NORTHERN IRELAND Susan McDermott No. 7 in the Discussion Series: Breaking the Patterns of Conflict Institute for British-Irish Studies University College Dublin IBIS Discussion Paper No. 7 ABSTRACT ANALYSING THE DEVELOPMENT OF BIPARTISANSHIP IN THE DÁIL: THE INTERACTION OF FINE GAEL AND FIANNA FÁIL PARTY POLITICS ON THE IRISH GOVERNMENT POLICY ON NORTHERN IRELAND This paper analyses the relationship between the two main parties in the Irish party system when dealing with the Northern Ireland question. -

Farewell to a Man, and to an Era

September 2009 VOL. 20 #9 $1.50 Boston’s hometown journal of Irish culture. Worldwide at bostonirish.com All contents copyright © 2009 Boston Neighborhood News, Inc. FAREWELL TO A MAN, AND TO AN ERA Cardinal Sean O’Malley, Archbishop of Boston, walked around the casket with incense before it left the church after the funeral Mass for Sen. Edward M. Kennedy at Our Lady of Perpetual Help Basilica in Boston on Sat., Aug. 29. (AP Photo/Brian Snyder, Pool) BY CAROL BEGGY the United States Senate” that family was celebrated for its bors on Caped Cod to world to come to Boston,” Cowen told SPECIAL TO THE BIR stretched from his corner of deep Irish roots. As the Boston leaders including Irish Prime the Boston Irish Reporter’s Joe From the moment the first Hyannis Port to Boston, Wash- Globe’s Kevin Cullen wrote, Minister Brian Cowen. Leary at the Back Bay Hotel, news bulletins started crackling ington, Ireland, the home of his the senator himself was slow “We’re very grateful for the formerly the Jurys Hotel. on radios and popping up on ancestors, the British Isles, and in embracing his Irish heritage, great dedication of Senator Ken- Michael Lonergan had barely BlackBerries late on the night beyond. but once he did, he made it his nedy to Ireland and its people,” sat in his seat as the new Consul of Tuesday, Aug. 25, the death This youngest brother of the mission to help broker peace in Cowen said at an impromptu General of Ireland in Boston of Senator Edward M. -

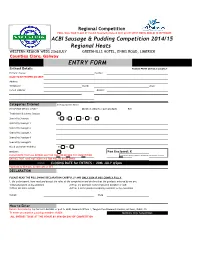

To Download Application Form for West

Regional Competition FINAL (NATIONALWILL TAKE FINAL PLACE WILL AT TAKEFood PLACE& Hospitality AT SHOP Ireland 2012 @2014 RDS @ in CITY September) WEST HOTEL DUBLIN IN SEPTEMBER ACBI Sausage & Pudding Competition 2014/15 Regional Heats WESTERN REGION WEDS 23rdJULY GREENHILLS HOTEL, ENNIS ROAD, LIMERICK Counties Clare, Galway ENTRY FORM Entrant Details PLEASE PRINT DETAILS CLEARLY Entrant's Name: Position: NAME TO BE PRINTED ON CERT: Address: Telephone: (work) (fax) e-mail address: Mobile: Categories Entered (tick appropriate boxes) PLEASE PRINT DETAILS CLEARLY Member entry fee (per product) €45 Traditional Butchers Sausage Speciality Sausage 1 2 3 4 5 Speciality Sausage 1 Speciality Sausage 2 Speciality Sausage 3 Speciality Sausage 4 Speciality Sausage 5 Black and White Pudding B W Drisheen Fee Enclosed: € PLEASE NOTE THAT ALL ENTRIES MUST BE PAID FOR BEFORE THE COMPETITION Please make cheques payable to Associated Craft Butchers of Ireland ENTRIES THAT HAVE NOT BEEN PAID FOR WILL BE DISALLOWED >>>> CLOSING DATE for ENTRIES : 20th JULY @5pm Payment by Cheque, Credit card or EFT DECLARATION PLEASE READ THE FOLLOWING DECLARATION CAREFULLY AND ONLY SIGN IF YOU COMPLY FULLY. I, the undersigned, have read and accept the rules of the competition and declare that the products entered by me are; 1) Manufactured on my premises 2) That the premises is the registered member of ACBI 3) That the meat is Irish 4) That it is the product normally available to my customers Signed Date How to Enter Return this form by by fax to 01-8682822 or post to ACBI, Research Office 1, Teagasc Food Research Centre, Ashtown, Dublin 15. -

Remembering 1916

Remembering 1916 – the Contents challenges for today¬ Preface by Deirdre Mac Bride In the current decade of centenary anniversaries of events of the period 1912-23 one year that rests firmly in the folk memory of communities across Ireland, north and south, is 1916. For republicans this is the year of the Easter Rising which led ultimately to the establishment of an independent THE LOCAL AND INTERNATIONAL CONTEXT: THE CHALLENGES republic. For unionists 1916 is remembered as the year of the Battle of the Somme in the First World AND COMPLEXITIES OF COMMEMORATION War when many Ulstermen and Irishmen died in the trenches in France in one of the bloodiest periods of the war. Ronan Fanning,”Cutting Off One's Head to Get Rid of a Headache”: the Impact of the Great War on the Irish Policy of the British Government How we commemorate these events in a contested and post conflict society will have an important How World War I Changed Everything in Ireland bearing on how we go forward into the future. In order to assist in this process a conference was organised by the Community Relations Council and the Heritage Lottery Fund. Entitled Éamon Phoenix, Challenging nationalist stereotypes of 1916 ‘Remembering 1916: Challenges for Today’ the conference included among its guest speakers eminent academics, historians and commentators on the period who examined the challenges, risks Northern Nationalism, the Great War and the 1916 Rising, 1912-1921 and complexities of commemoration. Philip Orr, The Battle of the Somme and the Unionist Journey The conference was held on Monday 25 November 2013 at the MAC in Belfast and was chaired by Remembering the Somme BBC journalist and presenter William Crawley. -

Report at a Glance

(SECTION 136 (2) OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT 2001, SECTION 51 OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT REFORM ACT 2014) COMHAIRLE CHONTAE CHILL CHAINNIGH KILKENNY COUNTY COUNCIL TUARASCÁIL BHAINISTÍOCHTA MÍOSÚIL MONTHLY MANAGEMENT REPORT EANAIR - JANUARY 2021 EXECUTIVE FUNCTIONS REPORT AT A A list of Orders made in the last month will be available in the Council Chamber for inspection GLANCE by the Elected Members. COMMUNICATION STATISTICS: .......... 4 DATES FOR YOUR DIARY CORPORATE: ......................................... 6 ROADS: ................................................. 7 Last Week January/First Week February Public consultation webinars will be published WATER SERVICES: ................................ 8 for Draft City and County Development Plan. PLANNING: ........................................... 9 PARKS: .................................................. 11 ENVIRONMENT: .................................... 15 COMMUNITY: ........................................ 24 HERITAGE: ............................................ 26 LEO/ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ....... 27 HOUSING: ............................................. 29 TOURISM: .............................................. 32 FIRE SERVICES: ..................................... 33 ARTS: ..................................................... 34 LIBRARY SERVICES: .............................. 40 1 (SECTION 136 (2) OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT 2001, SECTION 51 OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT REFORM ACT 2014) COMHAIRLE CHONTAE CHILL CHAINNIGH KILKENNY COUNTY COUNCIL TUARASCÁIL BHAINISTÍOCHTA MÍOSÚIL MONTHLY MANAGEMENT -

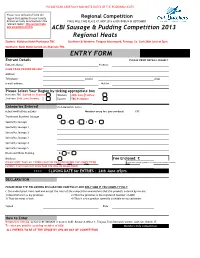

ENTRY FORM Entrant Details PLEASE PRINT DETAILS CLEARLY Entrant's Name: Position: NAME to BE PRINTED on CERT: Address: Telephone: (Work) (Fax) E-Mail Address: Mobile

PLEASE READ CAREFULLY AND NOTE DATES OF THE REGIONAL HEATS Please note on back of form the region that applies to your county. Regional Competition Entries will only be accepted in the (NATIONAL FINAL WILL FINAL TAKE WILL PLACE TAKE AT PLACESHOP 2013 AT SHOP @ RDS 2012 DUBLIN @ RDS IN inSEPTEMBER September) relevant region. We cannot make any exceptions to this ACBI Sausage & Pudding Competition 2013 Regional Heats Eastern: Maldron Hotel Portlaoise TBC Southern & Western: Teagasc Moorepark, Fermoy, Co. Cork 26th June at 3pm Northern: Bush Hotel Carrick-on-Shannon TBC ENTRY FORM Entrant Details PLEASE PRINT DETAILS CLEARLY Entrant's Name: Position: NAME TO BE PRINTED ON CERT: Address: Telephone: (work) (fax) e-mail address: Mobile: Please Select Your Region by ticking appropriate box Northern TBC Carrick on Shannon Western 26th June FermoyFermoy Southern 26th June Fermoy Eastern TBC Portlaoise Categories Entered (tick appropriate boxes) PLEASE PRINT DETAILS CLEARLY Member entry fee (per product) €45 Traditional Butchers Sausage Speciality Sausage 1 2 3 4 5 Speciality Sausage 1 Speciality Sausage 2 Speciality Sausage 3 Speciality Sausage 4 Speciality Sausage 5 Black and White Pudding B W Drisheen Fee Enclosed: € PLEASE NOTE THAT ALL ENTRIES MUST BE PAID FOR BEFORE THE COMPETITION Please make cheques payable to Associated Craft Butchers of Ireland ENTRIES THAT HAVE NOT BEEN PAID FOR WILL BE DISALLOWED >>>> CLOSING DATE for ENTRIES : 24th June @5pm DECLARATION PLEASE READ THE FOLLOWING DECLARATION CAREFULLY AND ONLY SIGN IF YOU COMPLY FULLY. I, the undersigned, have read and accept the rules of the competition and declare that the products entered by me are; 1) Manufactured on my premises 2) That the premises is the registered member of ACBI 3) That the meat is Irish 4) That it is the product normally available to my customers Signed Date How to Enter Return this form by by fax to 01-8682820 or post to ACBI, Research Office 1, Teagasc Food Research Centre, Ashtown, Dublin 15.