Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Seventh Season Being Mendelssohn CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 17–August 8, 2009 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Seventh Season Being Mendelssohn CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 17–August 8, 2009 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Music@Menlo Being Mendelssohn the seventh season july 17–august 8, 2009 david finckel and wu han, artistic directors Contents 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 5 Welcome from the Executive Director 7 Being Mendelssohn: Program Information 8 Essay: “Mendelssohn and Us” by R. Larry Todd 10 Encounters I–IV 12 Concert Programs I–V 29 Mendelssohn String Quartet Cycle I–III 35 Carte Blanche Concerts I–III 46 Chamber Music Institute 48 Prelude Performances 54 Koret Young Performers Concerts 57 Open House 58 Café Conversations 59 Master Classes 60 Visual Arts and the Festival 61 Artist and Faculty Biographies 74 Glossary 76 Join Music@Menlo 80 Acknowledgments 81 Ticket and Performance Information 83 Music@Menlo LIVE 84 Festival Calendar Cover artwork: untitled, 2009, oil on card stock, 40 x 40 cm by Theo Noll. Inside (p. 60): paintings by Theo Noll. Images on pp. 1, 7, 9 (Mendelssohn portrait), 10 (Mendelssohn portrait), 12, 16, 19, 23, and 26 courtesy of Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz/Art Resource, NY. Images on pp. 10–11 (landscape) courtesy of Lebrecht Music and Arts; (insects, Mendelssohn on deathbed) courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library. Photographs on pp. 30–31, Pacifica Quartet, courtesy of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. Theo Noll (p. 60): Simone Geissler. Bruce Adolphe (p. 61), Orli Shaham (p. 66), Da-Hong Seetoo (p. 83): Christian Steiner. William Bennett (p. 62): Ralph Granich. Hasse Borup (p. 62): Mary Noble Ours. -

Society of Musical Arts Stephen Culbertson, Music Director

Society of Musical Arts Stephen Culbertson, Music Director Concert Program Sunday, March 6, 2016 4:0 0 P.M. Maplewood Middle School 7 Burnet Street Maplewood, New Jersey his program is made possible in part by funds from the TNew Jersey State Council on the Arts/Department of State, a Partner Agency of the National Endowment for the Arts and administered by the Essex County Division of Cultural and Historic Affairs. SOMA gratefully acknowledges our grant from Essex County DCHA in the amount of $1,220 for the year 2016. 2 Orchestra November 2015 Stephen Culbertson, Music Director FIRST VIOLIN FLUTE FRENCH HORN Susan Heerema* Laura Paparatto* Paul Erickson* Barbara Bivin Gail Berkshire Dana Bassett Dan Daniels Brian Hill Faye Darack PICCOLO Linda Lovstad Emily Jones* Lea Karpman Libby Schwartz Naomi Shapiro OBOE TRUMPET Richard Waldmann Richard Franke* George Sabel* Melanie Zanakis Lynn Grice Darrell Frydlewicz SECOND VIOLIN ENGLISH HORN Robert Ventimiglia Len Tobias* John Cannizzarro* Iolanda Cirillo TROMBONE Jay Shanman* Kelly Fahey CLARINET John Vitkovsky Jim Jordan Donna Dixon* Phil Cohen Lillian Kessler Theresa Hartman Scott Porter Shirley Li TUBA Michael Schneider BASS CLARINET James Buchanan* Joel Kolk* VIOLA PIANO Roland Hutchinson* BASSOON Evan Schwartzman* Aidan Garrison Karen Kelland* HARP Mitsuaki Ishikawa William Schryba Nicholas Mirabile Patricia Turse* Peggy Reynolds CONTRABASSOON PERCUSSION Andrew Pecota* Joe Whitfield* CELLO James Celestino* ALTO SAXOPHONE John DeMan Arnie Feldman Paul Cohen* Evan Hause Megan Doherty Garrett -

North Carolina School of the Arts Bulletin 2002-2003

NORTH CAROLINA SCHOOL OF THE ARTS BULLETIN 2002-2003 Dance Design & Production Drama Filmmaking Music Visual Arts General Studies Graduate, undergraduate and secondary education for careers in the arts One of the 16 constituent institutions of the University of North Carolina Accredited by the Commission on Colleges of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools to award the Bachelor of Fine Arts in Dance, Design & Production, Drama, and Filmmaking and the Bachelor of Music; the Arts Diploma; and the Master of Fine Arts in Design & Production and the Master of Music. The School is also accredited by the Commission on Secondary Schools to award the high school diploma with concentrations in dance, drama, music, and the visual arts. This bulletin is published biennially and provides the basic information you will need to know about the North Carolina School of the Arts. It includes admission standards and requirements, tuition and other costs, sources of financial aid, the rules and regulations which govern student life and the School’s matriculation requirements. It is your responsibility to know this information and to follow the rules and regulations as they are published in this bulletin. The School reserves the right to make changes in tuition, curriculum, rules and regulations, and in other areas as deemed necessary. The North Carolina School of the Arts is committed to equality of educational opportunity and does not discriminate against applicants, students, or employees based on race, color, national origin, religion, gender, age, disability or sexual orientation. North Carolina School of the Arts 1533 S. Main St. Winston-Salem, NC 27127-2188 336-770-3290 Fax 336-770-3370 http://www.ncarts.edu 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Academic Calendar 2002-2004 .....................................................................................Pg. -

![North Carolina School of the Arts Bulletin [2000-2002]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5532/north-carolina-school-of-the-arts-bulletin-2000-2002-6535532.webp)

North Carolina School of the Arts Bulletin [2000-2002]

ARTS THE OF SCHOOL CAROLINA NORTH DANCE DESIGN £* PRODUCTION DRAMA FILMMAKING MUSIC VISUAL ARTS GENERAL STUDIES This bulletin is published biennially and provides the basic information you will need to know about the North Carolina School of the Arts. It includes admission standards and requirements, tuition and other costs, sources of financial aid, the rules and regulations which govern student life and the School's matriculation requirements. It is your responsibility to know this information and to follow the rules and regulations as they are published in this bulletin. The School reserves the right to make changes in tuition, curriculum, rules and regulations, and in other areas as deemed necessary. North Carolina. School oi the Ari s Training America's new generation of artists BULLETIN 2000-2002 Dance Design & Production Drama Filmmaking Music Visual Arts Graduate, undergraduate and secondary education for careers in the arts One of the 16 constituent institutions of the University of North Carolina Accredited by the Commission on Colleges of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools to award the Bachelor of Fine Arts in Dance, Design & Production, Drama, and Filmmaking and the Bachelor of Music; the Arts Diploma; and the Master of Fine Arts in Design & Production and the Master of Music. The School is also accredited by the Commission on Secondary Schools to award the high school diploma with concentrations in dance, drama, music, and the visual arts. 1533 S. Main St. Winston-Salem, NC 27127-2188 Telephone 336-770-3399 www.ncarts.edu l TABLE OF CONTENTS Academic Calendar 2000-2002 pg . 4 Mission Statement pg . -

Program Notes for February 19, 2017 Gustav Holst the Perfect Fool

Program Notes for February 19, 2017 Gustav Holst The Perfect Fool: Ballet Music, Op. 39 Gustav Holst was born in Cheltenham, England in 1874 and died in London in 1934. He composed his opera The Perfect Fool in 1918-1922 and it was first performed the following year at the Covent Garden Theater in London under the direction of Eugene Goossens. Holst composed the ballet music that precedes the opera in 1920. The score calls for 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, celeste, and strings. ***** Gustav Holst was a workaday musician. Arthritis in his hands precluded a career as a pianist, so for several years following college he made a living as a trombonist in opera and theater orchestras. Eventually he turned to teaching, sometimes at several schools at once, until he became head of the music department at the St. Paul’s School for Girls in London. His duties there were so time-consuming that he had little time left for composing. The ambivalence he had about composing thus stemmed from necessity, but he also said, “Never compose anything unless the not composing of it becomes a positive nuisance to you.” He found it a positive nuisance not to compose his short, comic opera The Perfect Fool, but alas both the audience and the critics simply found it a nuisance, period. The opera was a parody of 19th century opera conventions—and most especially those of Wagner—but it seemed there was no one who was ready to “get it.” This is mostly blamed on the libretto, written by Holst himself. -

New Goldberg Variations David Geringas Violoncello Ian Fountain Piano

New Goldberg Variations David Geringas violoncello Ian Fountain piano Q.er Deutschlandfunk Kultur ��o New Goldberg Variations Suite - zusammengestellt von David Geringas - Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) 1. Aria from Goldberg Variations BWV 988 for Piano solo 2:32 John Corigliano (* 1938) 2. Fancy on a Bach Air for Violoncello solo (1996) 4:17 Richard Danielpour (* 1956) 5:53 3. Fantasy Variation for Violoncello and Piano (1997) Adagietto misterioso Peter Lieberson (1946-2011) 4. Three Variations for Violoncello and Piano (1996) 4:52 Variation I – Neighbor Canons Variations II – Scherzo Variations III – Aria Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924) 5. Aria from Bach’s Goldberg Variations for Piano solo (1915) 2:29 Christopher Rouse (* 1949) 6. Goldberg Variations II: Ricordanza for Violoncello solo (1995) 3:45 Kenneth Frazelle (* 1955) New Goldberg Variations for Violoncello and Piano (1997) 7. Variation I – Molto Adagio 2:36 8. Variation II – Presto 2:10 Johann Sebastian Bach 9. Variatio 16 (Ouverture) from Goldberg Variations BWV 988 1:58 for Violoncello and Piano Peter Schickele (* 1935) New Goldberg Variations for Violoncello and Piano (1995) 10. Variation I – Calm, serene 4:38 11. Variation II – Driving 1:50 Johann Sebastian Bach 12. Aria from Goldberg Variations BWV 988 for Violoncello and Piano 2:37 Sonata in G Major BWV 1027 for Viola da Gamba und Harpsichord, Version for Violoncello and Piano 13. Adagio 3:33 14. Allegro ma non tanto 3:16 15. Andante 2:45 16. Allegro moderato 3:01 17. Air from Orchestral Suite No. 3 BWV 1068 4:58 for Violoncello und Piano David Geringas, violoncello Ian Fountain, piano Johann Gottlieb Goldberg war ein hochbegabter Musiker, der als Kind von dem Grafen Hermann Carl Keyserlingk gefördert wurde und auch in dessen Haus in Dresden als Haus- Cembalist wohnte. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1991

National Endowment for the Arts ~99I Annual Report NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR~THE ARTS ~99~ Annual Report NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR~THE ARTS Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts for the fiscal year Arts in Eduealion ended September 30, 1991. Challenge Respectfully, Anne-Imelda Radice Acting Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. July 1992 The Arts Endowment in Brief 6 The Year in Review The National Council on the Arts PROGRAMS Dance 15 Design Arts 3o Expansion Arts 42 Folk Arts 64 Inter-Arts 74 Literature 9o Media Arts IO2 Museum 116 Music I44 Opera-Musical Theater ~84 Theater I95 Visual Arts :2I3 Challenge 2:27 Advancement 236 OFFICE FOR PUBLIC PARTNERSHIP Arts in Education z43 Locals 254 State and Regional 259 Under-Served Communities Set-Aside 265 OFFICE OF POLICY, PLANNING, RESEARCH & BUDGET z75 Special Constituencies 276 Research 277 Arts Administration Fellows 279 International Activities 28I ADVANCEMENT, CHALLENGE AND OVERVIEW PANELS 286 FINANCIAL SUMMARY Fiscal Year 1991 297 History of Authorizations and Appropriations 298 Credits 303 Each summer "Jazz in July," at New York’s 92d Street Y, features immortals like bassist Milt Hinton with Arts Endowment help. The Arts Endowment in Brief stablished by Congress in 1965, the National of the National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities. Endowment for the Arts is the federal agency The Foundation is an umbrella organization, created by that supports the visual, literary and perform Congress, that also contains the National Endowment for E ing arts to benefit all Americans. -

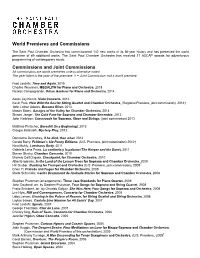

SPCO Premieres and Commissions

World Premieres and Commissions The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra has commissioned 142 new works in its 56-year history and has presented the world premiere of 49 additional works. The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra has received 17 ASCAP awards for adventurous programming of contemporary music. Commissions and Joint Commissions All commissions are world premieres unless otherwise noted The year listed is the year of the premiere. † = Joint Commission; not a world premiere Fred Lerdahl, Time and Again, 2015 Charles Wuorinen, MEGALITH for Piano and Orchestra, 2015 Nicolas Campogrande, Urban Gardens for Piano and Orchestra, 2014 Aaron Jay Kernis, Viola Concerto, 2014 Kevin Puts, How Wild the Sea for String Quartet and Chamber Orchestra, (Regional Premiere, joint commission), 2014† John Luther Adams, Become River, 2014 Mason Bates, Garages of the Valley for Chamber Orchestra, 2014 Shawn Jaeger, The Cold Pane for Soprano and Chamber Ensemble, 2013 John Harbison, Crossroads for Soprano, Oboe and Strings, (joint commission) 2013 Matthias Pintscher, Bereshit (In a Beginning), 2013 Giorgio Battistelli, Mystery Play, 2012 Donnacha Dennehey, if he died, then what, 2012 Gerald Barry, Feldman’s Six-Penny Editions, (U.S. Premiere, joint commission) 2012† Nico Muhly, Luminous Body, 2011 Gabriela Lena Frank, La centinela y la paloma (The Keeper and the Dove), 2011 Steven Stucky, Chamber Concerto, 2010 Michele Dall’Ongoro, Checkpoint, for Chamber Orchestra, 2010 Alberto Iglesias, In the Land of the Lemon Trees for Soprano and Chamber Orchestra, 2009 HK Gruber, Busking for Trumpet and Orchestra (U.S. Premiere, joint commission), 2009† Chen Yi, Prelude and Fugue for Chamber Orchestra, 2009 Maria Schneider, Carlos Drummond de Andrade Stories for Soprano and Chamber Orchestra, 2008 Stephen Prutsman (arrangements), Three Jazz Standards for Piano Quartet, 2008 John Dowland, arr.