Comprehensive Review and Assessment of Housing Issues in Yukon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Targeted Residential Fire Risk Reduction a Summary of At-Risk Aboriginal Areas in Canada

Targeted Residential Fire Risk Reduction A Summary of At-Risk Aboriginal Areas in Canada Len Garis, Sarah Hughan, Paul Maxim, and Alex Tyakoff October 2016 Executive Summary Despite the steady reduction in rates of fire that have been witnessed in Canada in recent years, ongoing research has demonstrated that there continue to be striking inequalities in the way in which fire risk is distributed through society. It is well-established that residential dwelling fires are not distributed evenly through society, but that certain sectors in Canada experience disproportionate numbers of incidents. Oftentimes, it is the most vulnerable segments of society who face the greatest risk of fire and can least afford the personal and property damage it incurs. Fire risks are accentuated when property owners or occupiers fail to install and maintain fire and life safety devices such smoke alarms and carbon monoxide detectors in their homes. These life saving devices are proven to be highly effective, inexpensive to obtain and, in most cases, Canadian fire services will install them for free. A key component of driving down residential fire rates in Canadian cities, towns, hamlets and villages is the identification of communities where fire risk is greatest. Using the internationally recognized Home Safe methodology described in this study, the following Aboriginal and Non- Aboriginal communities in provinces and territories across Canada are determined to be at heightened risk of residential fire. These communities would benefit from a targeted smoke alarm give-away program and public education campaign to reduce the risk of residential fires and ensure the safety and well-being of all Canadian citizens. -

Dwellings, Yukon and Census Subdivision

Yukon Bureau of Statistics 2÷9#1$>0-2+6&±8<3π7£5‡9≈1∞^ Population and Dwellings Census 2011 Population Growth by Province and Territory Highlights (2006 to 2011 Census Counts) • 33,897 people were counted in Yukon in May 2011. 11.6% • Yukon’s population growth of 11.6% between the 10.8% 2006 and 2011 census years was the highest in Canada average = 5.9% 8.3% Canada. 7.0% 6.7% 5.7% 5.2% • 80% of Yukon’s population growth took place in 4.7% Whitehorse. 3.2% 2.9% 1.8% • The total number of Yukon dwellings occupied by 0.9% 0.0% usual residents grew by 11.9%. YT AB NU BC SK ON MB QC PE NB NL NS NT In May 2011, Statistics Canada conducted a census of Cana- one exception (1996 to 2001 census years; due mainly to the dian residents. The data collected covered Canada, the prov- Faro mine closure). inces and territories, and down to community and municipal The growth in Yukon between 2006 and 2011 (which oc- areas. curred mainly in Whitehorse) was related to a net increase in In Yukon, data is categorized into 37 geographic census sub- the number of immigrants and non-permanent residents, as divisions. These subdivision types range from city down to well as a net increase in inter-provincial migration. very small parcels of land which have historic signifi- cance but no current population. Yukon Census Populations and Percent Growth The release of population and dwelling counts data (1956 to 2011 Census Counts) from the 2011 Census of Population marks the first of 40,000 40.0% four releases in 2012. -

Indian and Inuit Affairs Program

Indian and Inuit Affairs Program Program Planning and Policy Coordination SCHEDULE OF INDIAN BANDS, RESERVES AND SETTLEMENTS INCLUDING - MEMBERSHIP AND POPULATION APRIL 1, 1983 Programme des affaires indiennes et inuit Planification du programme et coordination des politiques RÉPERTOIRE DES BANDES, RÉSERVES ET ÉTABLISSEMENTS INDIENS - EFFECTIF ET POPULATION LE 1er AVRIL 1983 Source of information: Source de renseignements: Reserves and Trusts Reserves et fidéicommis Publication available from: Publication disponsible au: Program Reference Centre Centre de référence du programme Indian and Inuit Affairs Affaires indiennes et inuit Les Terrasses de la Chaudière Les Terrasses de la Chaudière Room 1610 - Telephone (819) 997-9117 Pièce 1610 - téléphone (819) 997-9117 10 Wellington Street 10, rue Wellington Hull, Quebec. Hull, (Québec) (c)Published under the authority Publié avec l'autorisation of the Hon. John C. Munro, de l'hon John C. Munro, P.C., M.P., Minister of c.p., député, ministre Indian Affairs and Northern des Affaires indiennes et du Nord canadien, Development, Ottawa, 1982 Ottawa, 1982. QS - 5177 - 000 - BB - A2 QS - 5177 - 000 - BB - A2 District Region - Région CENTRE DE SERVICE L'ABITIBI (CRIS) (372) VAL D'OR, QUEBEC ABITIBI QUEBEC (CREE) SERVICE CENTRE (372) VAL D'OR, QUEBEC Band - Bande Reserve/Settlement - Réserve/Établissement Identifier Band Identifier No. Name number Membership Name N° Population Nom N° Effectif de la Nom d'identification d'identification bande Dec. Dec. ... ... ... ... Déc. 31, Déc. 31, 1981 1980 Eastmain -

Profileproposal of Title the Alaska Highway

ECONOMIC PROFILEPROPOSAL OF TITLE THE ALASKA HIGHWAY Submitted to: Government of Yukon Department of Economic Development Prepared by: InterGroup Consultants Ltd. in association with PROLOG Canada February 2016 PRO LOG CANADA Economic Profile of the Alaska Highway February 2016 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This economic profile report examines how the Alaska Highway's traffic flows and ongoing operation make a difference today, and are expected to make a difference in the future, to valued economic and social components in those areas where the Highway is located, including public and private businesses, resource use, government, tourism, security and emergency response, and communities. The Alaska Highway (the “Highway”) is a key interjurisdictional corridor built during World War II as a secure inland military supply route. It extends from Dawson Creek in northeastern British Columbia to Fairbanks in Alaska, passing through Fort Nelson, B.C. and the southern areas of Yukon (including Watson Lake, Whitehorse and Haines Junction) as well as Tok and Delta Junction in Alaska. It includes the Haines Road connecting Haines Junction to the port of Haines, Alaska. The economic profile of the Highway is examined by considering the difference between economic and social effects of traffic flows and highway operation (1) “with the Highway” and (2) “without the Highway”, i.e., a scenario assuming an alternative transportation regime absent the key features of the Highway. Heavy commercial traffic activity entering and exiting Yukon through the Highway and other gateways was estimated in this study for 2014. Other Highway traffic and related Highway maintenance and capital costs were also examined. Scenario without the Highway - Alternative Transportation Regime Long before the Alaska Highway, "Inside Passage" or marine access was well developed for passengers and freight through the Alaska ports of Skagway (for access to and from Yukon) and Anchorage as well as Valdez (for access to and from interior Alaska). -

First Nation Community Profiles

FIRST NATION COMMUNITY PROFILES CARCROSS/TAGISH FIRST NATION - COMMUNITIES OF CARCROSS AND TAGISH COMPLIMENTS OF CTFN PHOTO GALLERY Carcross/Tagish First Nation History Traditional Culture and Heritage Spirituality is held in very high regard within the Carcross/Tagish First Nation. Ceremony is a very im- portant part of the people’s lives, following the transition of ages, spanning from birth to death, and encompassing the relationship with self, clan and nation. Art forms are used to express the people’s spiritual relationship and interconnectedness with one another, as well as with the land, water and animals. The First Nation’s crests and totems serve as keys to unlock a rich oral tradition of storytell- ing and sharing. The two moieties are Wolf (Gooch) and Crow (Yeitl). Tagish/Tlingit culture is matrilineal, following the mother’s line. Each moiety consists of several clans, with each clan belonging to either Wolf or Crow. The Carcross/Tagish area has six clans that are recognized: Daklaweidi, Yen Yedi, Deisheetaan, Ganaxtedi, Kookhittaan, and Ishkahittan. Daklaweidi (Killerwhale) and Yen Yedi (Wolf) are both Wolf Moieties. Deisheetaan (Beaver), Ganaxtedi (Raven), Kookhittaan (Crow), Ishkahittan (Frog) are all of Crow Moiety. The Carcross/Tagish First Nation is governed by what is known as a Clan System. Each clan is required to put forward their appointed leaders, who together will have the authority to make important de- cisions on behalf of all citizens of the Carcross/Tagish First Nation. Among the members who form the Executive Council, one person is appointed as the Khà Shâde Héni: the headman or chief. -

Amended Technical Report on the Mactung Property

Report to: Amended Technical Report on the Mactung Property Document No. 1053390100-REP-R0001-00 Suite 800, 555 West Hastings Street, Vancouver, British Columbia V6B 1M1 Phone: 604-408-3788 Fax: 604-408-3722 E-mail: [email protected] Report to: AMENDED TECHNICAL REPORT ON THE MACTURN PROPERTY EFFECTIVE DATE: APRIL 3, 2009 Prepared by: Honorio Narciso, P.Eng., Wardrop Engineering Inc. Iouri Iakovlev, P.Eng., Wardrop Engineering Inc. Marinus André de Ruijter, P.Eng., Wardrop Engineering Inc. Guy Impey, P.Eng., Wardrop Engineering Inc. Scott Cowie, MAusIMM, Wardrop Engineering Inc. Adrian Tanase, P.Eng., Wardrop Engineering Inc. Andy Nichols, P.Eng., MAN Mining Inc. Jay Collins, P.Eng., Merit Consultants International Inc. Nigel Goodall, Goodall Business Resource Management Ltd. Peter Lacroix, P.Eng., Scott Wilson Roscoe Postle Associates Inc. Richard Trimble, P.Eng., EBA Engineering Consultants Ltd. Suite 800, 555 West Hastings Street, Vancouver, British Columbia V6B 1M1 Phone: 604-408-3788 Fax: 604-408-3722 E-mail: [email protected] 1053390100-REP-R0001-00 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 GEOLOGY .......................................................................................................................... 1-2 1.1.1 MINERALIZATION ............................................................................................... 1-2 1.1.2 MINERAL RESOURCE ESTIMATE ........................................................................ -

Champagne & Aishihik First Nations

FIRST NATION COMMUNITY PROFILES CHAMPAGNE & AISHIHIK FIRST NATIONS - COMMUNITY OF HAINES JUNCTION COMPLiMENTS OF CAFN PHOTO GALLERY Champagne & Aishihik First Nations History The homeland of Champagne & Aishihik First Nations (CAFN), located in southwest Yukon and Northwest British Columbia, is a land of great natural beauty and biological richness. It is a land of steep mountains, surging glaciers, fast flowing rivers, rolling tundra plateau and forested river val- leys. CAFN was named after two of its historic settlements: Champagne, located on the Dezadeash River; and Aishihik, situated at the headwaters of the Alsek River drainage. Formerly, the South- ern Tutchone population was located throughout the region in other villages including Kloo Lake, Klukshu, Canyon, Shäwshe and Hutshi. Of Yukon’s fourteen First Nations, CAFN is one of the largest. Its traditional territory covers 41,000 square kilometers, 29,000 of which are located in Yukon and 12,000 in British Columbia. Centred on Haines Junction, the easterly portion of CAFN’s traditional territory lies in the Yukon River watershed, while the larger, westerly portion lies in the Alsek River watershed. Much of Kluane National Park (Yukon) and all of Tatshenshini-Alsek Park (BC) lie within CAFN’s traditional territory. Cultural Connections CAFN’s native language is Southern Tutchone, a member of the Athapaskan language family, which includes Navajo, the Dene languages and most Yukon Indian languages. Strong ties with neigh- bouring Southern Tutchone First Nations, Kluane First Nation to the northwest and Ta’an First Nation to the east, have long been strengthened by intermarriage and visiting. CAFN has also maintained strong trading relationships with its neighbours to the south, the Tlingits of the Pacific Coast. -

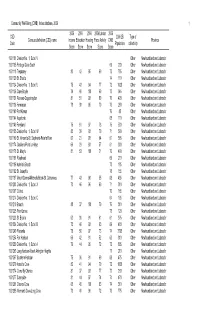

Community Well-Being (CWB) Index Database, 2006 1 CSD Code

Community Well-Being (CWB) Index database, 2006 1 2006 2006 2006 2006 Labour 2006 CSD 2006 2B Type of Census subdivision (CSD) name Income Education Housing Force Activity CWB Province Code Population collectivity Score Score Score Score Score 1001101 Division No. 1, Subd. V Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001105 Portugal Cove South 69 230 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001113 Trepassey 80 42 95 69 72 755 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001120 St. Shott's 74 110 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001124 Division No. 1, Subd. U 75 43 94 77 72 1620 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001126 Cape Broyle 74 49 100 69 73 545 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001131 Renews-Cappahayden 81 51 93 80 76 420 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001136 Fermeuse 78 38 95 70 70 250 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001140 Port Kirwan 76 85 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001144 Aquaforte 68 110 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001149 Ferryland 75 51 97 78 75 530 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001155 Division No. 1, Subd. W 83 39 93 70 71 560 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001169 St. Vincent's-St. Stephen's-Peter's River 67 21 93 64 61 365 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001174 Gaskiers-Point La Haye 66 29 93 57 61 300 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001178 St. Mary's 81 53 100 71 76 460 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001181 Riverhead 69 210 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001186 Admirals Beach 73 185 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001192 St. Joseph's 78 155 Other Newfoundland and Labrador 1001197 Mount Carmel-Mitchells Brook-St. -

Population & Dwellings PM

Census ‘96 Population and Dwelling Counts The following statistics are the first release from the 1996 Census of Canada which occurred on May 14, 1996. 1 Highlights ● The population of the Yukon, as enumerated by the 1996 Census, on May 14, 1996, was 30,766, just under 3,000 (10.7%) more than in 1991 (27,797). ● In 1996, 60% of the Yukon’s population lived in urban areas, almost the same as in 1991. ● The number of occupied private dwellings in the Yukon climbed to 11,584 in 1996, from 9,915 in 1991. Population and Dwelling Counts 2 Canada, Provinces and Territories 1996 Census 1991 Census '91 to '96 1996 Census Population Population % Change Dwellings Canada 28,846,761 27,296,859 5.7 10,899,427 Newfoundland 551,792 568,474 -2.9 187,406 Prince Edward Island 134,557 129,765 3.7 48,630 Nova Scotia 909,282 899,942 1.0 344,779 New Brunswick 738,133 723,900 2.0 272,915 Quebec 7,138,795 6,895,963 3.5 2,849,149 Ontario 10,753,573 10,084,885 6.6 3,951,326 Manitoba 1,113,898 1,091,942 2.0 421,096 Saskatchewan 990,237 988,928 0.1 375,740 Alberta 2,696,826 2,545,553 5.9 984,275 British Columbia 3,724,500 3,282,061 13.5 1,433,533 Yukon 30,766 27,797 10.7 11,584 Northwest Territories 64,402 57,649 11.7 18,994 3 1996 Census Population May 1996 Population 4 Estimates, Yukon -------Population------- Health Care Files % 1996 1991 Change Population Yukon 30,766 27,797 10.7 Yukon 32,682 Beaver Creek 131 104 26.0 Beaver Creek 140 Burwash Landing 58 77 -24.7 Burwash Landing 84 Carcross* 277 273 1.5 Carcross 424 Carmacks 466 349 33.5 Carmacks 476 Dawson 1,287 1,089 18.2 Dawson 2,013 Destruction Bay 34 32 6.3 Destruction Bay 47 Faro 1,261 1,221 3.3 Faro 1,255 Haines Junction 574 477 20.3 Haines Junction 821 Ibex Valley 322 240 34.2 Ibex Valley - Keno Hill 24 36 -33.3 Keno Hill - Mayo 324 243 33.3 Mayo 501 Mt. -

Site Screening Inventory (Part 1 of 2)

Yukon Next Generation Hydro and Transmission Viability Study: Site Screening Inventory (Part 1 of 2) Submitted By: Midgard Consulting Incorporated Date: January 12, 2015 Midgard Consulting Inc 828 – 1130 West Pender St. +1 (604) 298 4997 Vancouver BC, Canada midgard-consulting.com V6E 4A4 Executive Summary The Yukon Development Corporation (“YDC”) has commissioned Midgard Consulting Incorporated (“Midgard”) and its team of sub-consultants to complete the Yukon Next Generation Hydro and Transmission Viability Study. The study, delivered through a series of technical papers, is intended to help inform the decisions necessary to fill the territory’s growing energy gap and to support the Yukon’s continued economic growth and development. This report, the Site Screening Inventory, is the first of a series of technical papers with the goal of identifying, evaluating, categorizing, and ranking potential hydroelectric projects in the context of current economic, environmental, and societal expectations. To facilitate feedback, refinement, and transparency, the Site Screening Inventory is divided into two parts: 1) Part 1 (This Report) – At the end of three stages of screening (Screen 0, Screen 1, and Screen 2) 16 sites of interest remain for further study. The initial three screening stages include: reconciliation of known sites, screening for fundamental development barriers, and screening for fundamentally uneconomic sites. 2) Part 2 – Taking the 16 sites identified in Part 1, Part 2 contains a ranking (Ranking 3) that has the following sub-components: assessment of a project’s ability to meet the capacity and energy requirements of the Yukon grid, investigation of key environmental considerations, investigation of key socioeconomic considerations, and updated economics. -

Liard First Nation Status of Land Claim Negotiations

FIRST NATION COMMUNITY PROFILES LIARD FIRST NATION - COMMUNITIES OF WATSON LAKE & UPPER LIARD COMPLIMENTS OF YTG PHOTO GALLERY Liard First Nation History Watson Lake is often called The Gateway to Yukon. The community is located in the southeastern corner of Yukon, just 14 kilometres from where the Alaska Highway crosses the British Columbia border. Watson Lake is a key transportation hub; it sits at the junction of the Alaska Highway, the Robert Campbell Highway to central Yukon and the Northwest Territories, and the Stewart-Cassiar Highway from central British Columbia. Yukon’s capital, Whitehorse, is 455 kilometres to the northwest of Watson Lake. The community of Watson Lake consists of the town of Watson Lake and the adjoining settlements of the Liard First Nation, including Upper Liard, Two-Mile Village and Two and a Half Mile Village. Watson Lake lies within the traditional territory of the Liard First Nation, part of the Kaska Tribal Council. A community was established at Watson Lake in 1939, when the Canadian government decided to build a chain of airports across the North. The new community was a supply and accommodation centre for airport construction in 1941 and for the building of the Alaska Highway a year later. Upon completion of these projects, Watson Lake became a ser- vice centre for the highway and, later, for the resource-rich region of the upper Liard River and its tributaries. The Kaska language of the Liard First Nation is one of the Athapaskan languages. The Liard First Nation people are closely related to the Kaska Dena of Ross River. -

Proquest Dissertations

Kaska language socialization, acquisition and shift Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Meek, Barbra Allyn Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 22:38:22 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/290390 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has t)een reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter foce, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality^ illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author dkl not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g.. maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing firom left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6* x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an addittonal charge.