Targeting the HIV Epidemic in South Africa: the Need for Testing and Linkage to Care in Emergency Departments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report No. 11 of 2021/22 on an Investigation Into Allegations Of

REPORT OF THE PUBLIC PROTECTOR IN TERMS OF SECTION 182(1)(b) OF THE CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA, 1996 AND SECTION 8(1) OF THE PUBLIC PROTECTOR ACT, 1994 REPORT No: 11 OF 2021/22 ISBN No: 978-1-77630-036-5 “Allegations of worsening conditions within the health facilities/hospitals in the Eastern Cape Province” REPORT ON AN INVESTIGATION INTO ALLEGATIONS OF WORSENING CONDITIONS WITHIN THE HEALTH FACILITIES/HOSPITALS IN THE EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE REPORT ON AN INVESTIGATION INTO ALLEGATIONS OF WORSENING CONDITIONS WITHIN THE HEALTH FACILITIES/HOSPITALS IN THE EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………… 3 1. INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………….………..14 2. OWN INITIATIVE INVESTIGATION……………….…………………………..17 3. POWERS AND JURISDICTION OF THE PUBLIC PROTECTOR…………20 4. THE INVESTIGATION………………………………………………………… 25 5. THE DETERMINATION OF ISSUES IN RELATION TO THE EVIDENCE OBTAINED AND CONCLUSIONS MADE WITH REGARD TO THE APPLICABLE LAW AND PRESCRIPTS……………………………………..29 6. FINDINGS…………………………………………………………………….…..96 7. REMEDIAL ACTION………………………………………………………….....100 8. MONITORING…………………………………………….………………….......106 2 REPORT ON AN INVESTIGATION INTO ALLEGATIONS OF WORSENING CONDITIONS WITHIN THE HEALTH FACILITIES/HOSPITALS IN THE EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY (i) This is a report of the Public Protector issued in terms of section 182(1)(b) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 (the Constitution), and section 8(1) of the Public Protector Act, 1994 (Public Protector Act). (ii) The report communicates the findings and appropriate remedial action that the Public Protector is taking in terms of section 182(1)(c) of the Constitution, following an investigation into allegations of worsening conditions within the health facilities/hospitals in the Eastern Cape province. -

Covid-19 Sentinel Hospital Surveillance for Hcws Report – Update

COVID-19 Sentinel Hospital Surveillance Weekly Update on Hospitalized HCWs Update: Week 31, 2020 Compiled by: Epidemiology and Surveillance Division National Institute for Occupational Health 25 Hospital Street, Constitution Hill, Johannesburg This report summarises data of COVID-19 cases admitted to sentinel hospital surveillance sites in all 1 provinces. The report is based on data collected from 5 March to 1 August 2020 on the DATCOV platform. HIGHLIGHTS As of 1 August 2020, 883 (2.0%) of the 43943 COVID-19 hospital admissions recorded on the DATCOV surveillance database, were health care workers (HCWs), reported from 153 facilities (39 public-sector and 114 private-sector) in all nine provinces of South Africa. Among 327/883 (37.0%) HCWs with available data on type of work, 227/327 (69.4%) were nurses, 40/327 (12.2%) porters or administrators, 24/327 (7.3%) allied HCWs, 22/327 (6.7%) doctors, 9/327 (2.8%) paramedics, and 5/327 (1.5%) laboratory scientists. There was an increase of 116 new HCW admissions since week 30. There were 177 (20.1%) and 706 (79.9%) admissions reported in the public and private sector, respectively. The majority of HCW admissions were reported in Gauteng (275, 31.1%), KwaZulu-Natal (253, 28.7%), Western Cape (112, 12.7%), and Eastern Cape (81, 9.2%). The median age of COVID-19 HCW admissions was 45 years, there were 89 (10.1%) admissions in HCWs aged 60 years and older. A total of 702 (79.5%) were female. Among 824 (93.3%) HCW admissions with data on comorbid conditions, 402/824 (48.8%) had at least one comorbid condition and 148/402 (36.8%) had more than one comorbidity reported. -

The Knowledge of the Registration of the Role of the Doula in the Facilitation of Natural Child Birth

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stellenbosch University SUNScholar Repository THE KNOWLEDGE OF THE REGISTRATION OF THE ROLE OF THE DOULA IN THE FACILITATION OF NATURAL CHILD BIRTH Nonkululeko Veronica Kaibe Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Nursing in the Faculty of Health Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Dr ELD Boshoff March 2011 DECLARATION By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. ___________________________ __________________________ Nonkululeko Veronica Kaibe Date Copyright © 2011 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My understanding of the needs of mothers’ during labour developed with my experience in teaching student nurses on training midwifery course, both the 4 year diploma and the one- year diploma. Working as a registered midwife for the past 14 years also made me realise that there was a need for ongoing support for a woman giving birth. I would like to express my thanks and gratitude to the following people: God Almighty for the strength and wisdom he gave me during this study My friends for their continuous support and encouragement My supervisor, Dr Dorothy Boshoff, for her patience, guidance and understanding; I would never have managed without her. -

Registrar Advert 2021

ANNUAL REGISTRAR RECRUITMENT FOR 2021 The Eastern Cape Department of Health (ECDoH) in conjunction with the Faculty of Health Sciences of Walter Sisulu University (WSU) hereby invites applications from qualified Medical Practitioners who meet the following criteria to apply for Registrar REPLACEMENT posts: 1. Two years clinical experience after Community Service within the province. 2. Successful completion of CMSA diploma and Part 1 examinations relevant to the discipline – will be an added advantage where applicable. 3. Reasonable proficiency in speaking local language(s) and evidence of a long term commitment to the Eastern Cape Province will add weight to an application. 4. Priority will be given to Medical Officers employed in the ECDoH who are interested in specialties prioritised by the ECDoH in terms of its service imperatives. 5. Where a Medical Officer does not meet all these requirements, his/her application may be considered and will be based on: a. An excellent performance rating over the recent period in particular in the CMSA examinations; b. The rarity of the specialty which is a need in the department an applicant wishes to pursue; c. An absence of local applications from doctors in particular disciplines who meet the above requirements with motivation from the relevant HOD. These Registrar posts are available at the below-mentioned institutions: Frère Hospital & Cecilia Makiwane Hospital; Livingstone Hospital / Port Elizabeth Provincial Hospital; Dora Nginza Hospital & Elizabeth Donkin Hospital; Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital; Mthatha General Hospital and Bedford Orthopedics Hospital; Fort England Psychiatric Hospital; Komani Psychiatric Hospital and Frontier Hospital. 1 Kindly indicate your preferred institution on the Z83. -

Health Professions Act: List of Approved Facilities for the Purposes

STAATSKOERANT, 16 OKTOBER 2013 No. 36936 39 No. 791 16 October 2013 HEALTH PROFESSIONS ACT, 1974 (ACT NO. 56 OF 1974) LIST OF APPROVED FACILITIES FOR THE PURPOSES OF PERFORMING COMMUNITY SERVICE BY MEDICAL PRACTITIONERS IN THE YEAR 2014 The Minister of Health has, in terms of regulation 5.1 of the Regulations relating to Performance of Community Service by Persons Registering in terms of the Health Professions Act, 1974 (Act No. 56 of 1974), listed the following approved facilities for purposes of the profession of medicine. PROVINCE REGION/DISTRICT FACILITY EASTERN CAPE Alfred Nzo Khotsong Hospital* Madzikane kaZulu Hospital ** Umzimvubu Cluster Mt Ayliff Hospital** Taylor Bequest Hospital* (Matatiele) Amathole Bhisho CHH Cathcart Hospital * Amahlathi/Buffalo City Cecilia Makiwane Hospital Cluster Dimbaza CHC Duncan Village Day Hospital Empilweni Gompo CHC Fort Grey TB Hospital Frere Hospital Grey Hospital * Komga Hospital Nkqubela TB Hospital Nompumelelo Hospital* SS Gida Hospital* Stutterheim FPA Hospital* Mnquma Sub-District Butterworth Hospital* Nqgamakwe CHC* Nkonkobe Sub-District Adelaide FPA Hospital Tower Hospital* Victoria Hospital * Mbashe /KSD District Elliotdale CHC* Idutywa CHC* Madwaleni Hospital* Chris Hani All Saints Hospital** Engcobo/IntsikaYethu Cofimvaba Hospital** Martjie Venter FPA Hospital This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za 40 No. 36936 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 16 OCTOBER 2013 Sub-District Mjanyana Hospital * InxubaYethembaSub-Cradock Hospital** Wilhelm Stahl Hospital** District Inkwanca -

Health Professions Act: List of Approved Facilities for Community Service by Pharmacists in 2012

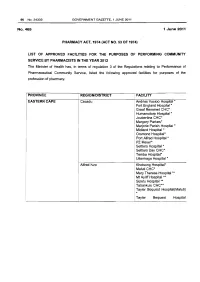

96 No.34332 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 1 JUNE 2011 No.465 1 June 2011 PHARMACY ACT, 1974 (ACT NO. 53 OF 1974} LIST OF APPROVED FACILITIES FOR THE PURPOSES OF PERFORMING COMMUNITY SERVICE BY PHARMACISTS IN THE YEAR 2012 The Minister of Health has, in terms of regulation 3 of the Regulations relating to Performance of Pharmaceutical Community Service, listed the following approved facilities for purposes of the profession of pharmacy. PROVINCE REGION/DISTRICT FACILITY EASTERN CAPE Cacadu Andries Vosloo Hospital * Fort England Hospital* Graaf Reneinet CHC* Humansdorp Hospital * Joubertina CHC* Margery Parkes* Marjorie Parish Hospital* Midland Hospital * Orsmond Hospital* Port Alfred Hospital * PZ Meyer* Settlers Hospital * Settlers Day CHC* Temba Hospital• Uitenhage Hospital * Alfred Nzo Khotsong Hospital• Maluti CHC* Mary Theresa Hospital .... ! Mt Ayliff Hospital ** · Sipetu Hospital •• Tabankulu CHC*• Tayler Bequest Hospitai(Maluti) * Tayler Bequest Hospital STAATSKOERANT, 1 JUNIE 2011 No. 34332 97 (Matatiele )"' Chris Hani All Saints Hospital ..... Cala Hospital ** Cofimvaba Hospital ** Cradock Hospital ** Elliot Hospital ... Frontier Hospital * Glen Grey Hospital * Mjanyana Hospital ** NgcoboCHC* Ngonyama CHC* Nomzamo CHC* Sada CHC* Thornhill CHC* Wilhelm Stahl Hospital ..... ZwelakheDalasile CHC* Nelson Mandala Dora Nginza Hospital Elizabeth Donkin Hospital Jose Pearson Santa Hospital Kwazakhele Day Clinic Laetitia Bam CH C Livingstone Hospital Motherwell CHC New Brighton CHC PE Pharmaceutical Depot PE Provincial Hospital Amathole Bedford Hospital Bhisho Hospital Butterworth Hospital Cecilia Makiwane Hospital Cathcart Hospital Dimbaza CHC Duncan Village Day CHC Dutywa CHC Empilweni Gompo CHC Fort Beauford Hospital Fort Grey Hospital Frere Hospital Grey Hospital Middledrift CHC Nontyatyambo CHC Nompomelelo Hospital Ngqamakwe CHC SS Gida Hospita Tafalofefe Hospital Tower Hospital Victoria Hospital Winterberg Hospital Willowvale CHC 98 No. -

We Are Here to Serve You During Covid-19 Lockdown

WE ARE HERE TO SERVE YOU DURING COVID-19 LOCKDOWN EASTERN CAPE PREMIER LUBABALO OSCAR MABUYANE Province of the EASTERN CAPE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA HEALTH FACILITIES Our team of health practitioners provide selfless services to all citizens who are in need of health care services. All these facilities are ready to service you, These include: 768 Primary health care clinics 66 District hospitals 5 Regional hospitals 3 Tertiary/Academic hospitals Province of the EASTERN CAPE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA TRACING OF COVID-19 PATIENTS Health Professionals, Traditional Leaders,Ward Councillors and Community Development Officers, will visit various areas tracing citizens who have potentially contracted COVID-19. The purpose of contact tracing and monitoring is to interrupt the spread of the COVID-19 from one person to another. If you were in contact with someone who tested positive of COVID-19, please report to the nearest health facility. Encourage family members to wash hands with soap and water for twenty seconds! Sanitise! Keep social distance of 1,5metres or more! Obey lockdown regulations. #FlattenTheCurve Province of the EASTERN CAPE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA MASS TESTING AND SCREENING Massive screening and testing will be conducted, prioritising areas with known cases and contacts of people with COVID-19. Eight mobile testing facilities have been assigned targeting four(4) hot spots in the Province i.e. Buffalo City Municipality , Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality Metro O R Tambo District Municipality , Sarah Baartman District Municipality. The Mass Screening and Testing Campaign was recently launched in Port Elizabeth. Be a more active citizen participate get tested. -

Accredited COVID-19 Vaccination Sites Eastern Cape

Accredited COVID-19 Vaccination Sites Eastern Cape Permit Primary Name Address Number 202103960 Fonteine Park Apteek 115 Da Gama Rd, Ferreira Town, Jeffreys Bay Sarah Baartman DM Eastern Cape 202103949 Mqhele Clinic Mpakama, Mqhele Location Elliotdale Amathole DM Eastern Cape 202103754 Masincedane Clinic Lukhanyisweni Location Amathole DM Eastern Cape 202103840 ISUZU STRUANWAY OCCUPATIONAL N Mandela Bay MM CLINIC Eastern Cape 202103753 Glenmore Clinic Glenmore Clinic Glenmore Location Peddie Amathole DM Eastern Cape 202103725 Pricesdale Clinic Mbekweni Village Whittlesea C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103724 Lubisi Clinic Po Southeville A/A Lubisi C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103721 Eureka Clinic 1228 Angelier Street 9744 Joe Gqabi DM Eastern Cape 202103586 Bengu Clinic Bengu Lady Frere (Emalahleni) C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103588 ISUZU PENSIONERS KEMPSTON ROAD N Mandela Bay MM Eastern Cape 202103584 Mhlanga Clinic Mlhaya Cliwe St Augustine Jss C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103658 Westering Medicross 541 Cape Road, Linton Grange, Port Elizabeth N Mandela Bay MM Eastern Cape Updated: 30/06/2021 202103581 Tsengiwe Clinic Next To Tsengiwe J.P.S C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103571 Askeaton Clinic Next To B.B. Mdledle J.S.School Askeaton C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103433 Qitsi Clinic Mdibaniso Aa, Qitsi Cofimvaba C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103227 Punzana Clinic Tildin Lp School Tildin Location Peddie Amathole DM Eastern Cape 202103186 Nkanga Clinic Nkanga Clinic Nkanga Aa Libode O Tambo DM Eastern Cape 202103214 Lotana Clinic Next To Lotana Clinic Lotana -

Port Elizabeth's Tertiary Care Reaches Crisis Point

Izindaba Port Elizabeth’s tertiary care reaches crisis point district hospitals and clinics that rely on them exclusively for referral – with potentially fatal effects when inter-disciplinary care is required. When Dr Siva Pillay was shown the letters by Izindaba, he expressed the ‘utmost respect’ for ‘most’ of the specialists who were ‘fighting a genuine battle that needs to be fought’. However, he said, had they spoken to him, they would have learnt that he had smoothed out the human resource process ‘so that we can now fast-track appointments’, and that his recent intervention with national treasury had led to a resetting of his health budget to include the R1.5 billion in overdraft and unauthorised expenditure previously earmarked for immediate repayment. In terms of recent political manoeuvring, a provincial co-ordinating and monitoring team now vets all appointments and provincial treasury has taken over the PERSAL (personnel L - R: Dr Lungile Pepeta, Paediatric Chief at Dora Nginza Hospital, Dr Basil Brown, Cardiology Chief salary) function and, said Pillay: ‘They don’t at Port Elizabeth Provincial Hospital and Professor Sats Pillay, Head of Surgery at Livingstone Hospital, understand the urgency of it’.1 at their ‘rebel’ Port Elizabeth press conference on 26 June this year. Dual loyalties again to Almost across disciplines, health care in country-wide since. Eastern Cape Health the fore the Port Elizabeth Provincial Hospital Director General, Dr Siva Pillay, angered Professor Sats Pillay, Head of Surgery at Complex (PEPHC) has -

Cohsasa News Sept 06

CohsasaThe Newsletter The Council for Health Service Accreditation of Southern Africa TECHNOLOGY UPDATE OCTOBER 2006 New information system is a treasure map COHSASA – in partnership with Xylaco Software – has developed a unique application, which will provide a 360-degree view of strengths, weaknesses and Ten South African urgent improvements needed in health facilities enrolled in COHSASA’s quality hospices accredited improvement and accreditation programmes. Ten hospices in the country, all members of the Hospice Palliative Care Association of Examining 37 areas of operation and measuring both clinical and non- South Africa, have been accredited clinical performance indicators, the new database, migrated from for two years, having met the COHSASA’s multiple legacy databases, will be able to provide professional quality standards clients with quick and easy access to a treasure trove of of COHSASA. information about their hospitals. A total of 47 members of Want to know how your hospital shapes up with regard to the Association entered the infection control? Get your access code, connect on-line and accreditation programme. the COHSASA information system will tell you exactly how Grahamstown Hospice you stand against professional standards, how various was the first to be departments associated with infection control are managing, accredited, followed by what criteria they are meeting and urgent deficiencies that nine others, which have met must be promptly addressed. stringent requirements for Moreover, if you are in the COHSASA Facilitated REWARDING QUALITY: Chairman of COHSASA, the provision of palliative care. Accreditation Programme, you can monitor staff progress and Albert Ramukumba, hands over the accreditation award to the Nursing Services Director of St Francis They were rated on standards pinpoint the bottlenecks and delays. -

COVID-19 Sentinel Hospital Surveillance Weekly Update on Hospitalized Hcws

COVID-19 Sentinel Hospital Surveillance Weekly Update on Hospitalized HCWs Update: Week 36, 2020 Compiled by: Epidemiology and Surveillance Division National Institute for Occupational Health 25 Hospital Street, Constitution Hill, Johannesburg This report summarises data of COVID-19 cases admitted to sentinel hospital surveillance sites in all 1 provinces. The report is based on data collected from 5 March to 5 September 2020 on the DATCOV platform. HIGHLIGHTS As of 5 September 2020, 2 686 (4.2%) of the 64 705 COVID-19 hospital admissions recorded on the DATCOV surveillance database, were health care workers (HCWs), reported from 247 facilities (81 public-sector and 166 private-sector) in all nine provinces of South Africa. Among 801/2686 (29.8%) HCWs with available data on type of work, 391/801 (48.8%) were nurses, 168/801 (21.0%) were categorized as other HCWs, 111/801 (13.9%) porters or administrators, 57/801 (7.1%) allied HCWs, 52/801 (6.5%) doctors, 15/801 (1.9%) paramedics, and 7/801 (0.9%) laboratory scientists. There was an increase of 157 new HCW admissions since week 35. There were 360 (13.4%) and 2326 (86.6%) admissions reported in the public and private sector, respectively. The majority of HCW admissions were reported in Gauteng (834, 31.1%), KwaZulu-Natal (656, 24.4%), Eastern Cape (465, 17.3%) and Western Cape (281, 10.5%). The median age of COVID-19 HCW admissions was 49 years, there were 482 (17.9%) admissions in HCWs aged 60 years and older. A total of 1912 (71.2%) were female. -

Covid-19 Sentinel Hospital Surveillance Update South Africa Week 32 2020

COVID-19 SENTINEL HOSPITAL SURVEILLANCE UPDATE SOUTH AFRICA WEEK 32 2020 OVERVIEW This report summarises data of COVID-19 cases admitted to sentinel hospital surveillance sites in all provinces. The report is based on data collected from 5 March to 8 August 2020. HIGHLIGHTS ∙ As of 8 August, 49218 COVID-19 admissions were reported from 380 facilities (144 public-sector and 236 private-sector) in all nine provinces of South Africa. There was an increase of 5177 new admissions since the last report, and 40 additional hospitals (35 public-sector and 5 private-sector) reporting COVID-19 admissions. There were 15503 (32%) and 33625 (68%) admissions reported in public and private sector respectively. The majority of COVID-19 admissions were reported from four provinces, 15782 (32%) in Western Cape, 14122 (29%) in Gauteng, 7824 (16%) in KwaZulu-Natal and 4306 (9%) in Eastern Cape. Admissions in the Western Cape, Eastern Cape and Gauteng have decreased and there are indications of slowing of the rate of increase in admissions in the other provinces over the past three weeks. ∙ ∙ Of the 49128 admissions, 6723 (14%) patients were in hospital at the time of this report, 34667 (71%) patients were discharged alive or transferred out and 7655 (16%) patients had died. There were 1028 additional deaths since the last report. ∙ ∙ Of the 41841 COVID-19 patients who had recorded in-hospital outcome (died and discharged), the case fatality ratio (CFR) was 18%. On multivariable analysis, factors associated with in-hospital mortality were older age groups; male sex; Black African and Coloured race; admission in the public sector; and having comorbid hypertension, diabetes, chronic cardiac disease, chronic renal disease, malignancy, HIV, current tuberculosis alone or both current and past tuberculosis, and obesity.