Prosopis Juliflora Scientific Name Prosopis Juliflora (Sw.) DC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of the Riparian Corridor in Big Bend National Park 1

Terrestrial Mammals of the Riparian Corridor in Big Bend National Park 1 William J. Boeer and David J. Schmidly2 Abstract.--Thirty species of terrestrial mammals inhabit riparian habitats in Big Bend National Park (BBNP), but only one species (the beaver, Castor canadensis) is restricted to these areas. Major changes in the vegetation during the past 30 years, involving an increase in basal and canopy cover, have resulted in the elimination of at least one species (Dipodomys ordii) from the river corridor as well as increased abundance and distribution for two other species (Sigmodon hispidus and Peromyscus leucopus). Compared to the other major plant communities in BBNP, the rodent fauna of the riparian community has lower evenness, richness, and diversity indices (based on the Shannon-Weaver Index). Humqn use and trespass livestock grazing are the major impacts acting upon the natural riparian communities in BBNP today. INTRODUCTION DESCRIPTION OF THE RIPARIAN CORRIDOR Mammalian studies of the Big Bend area began Floodplain or riparian vegetation exists with general surveys (Bailey 1905; Johnson 1936; wherever periodic flooding occurs along the Borell and Bryant 1942; and Taylor et al. 1944) Rio Grande in BBNP. These riparian communities designed to identify and document the varied vary from areas a few meters (m) wide to areas fauna of the area. After the park was esta extending inland a distance of one kilometer blished, the perspective of mammalian research (km); furthermore, adjacent arroyos and creeks changed somewhat and in recent years studies may carry enough surface or ground water to have concentrated on mammalian autecology and produce a similar floodplain environment. -

Mapping Prosopis Glandulosa (Mesquite) Invasion in the Arid Environment of South Africa Using Remote Sensing Techniques

Mapping Prosopis glandulosa (mesquite) invasion in the arid environment of South Africa using remote sensing techniques NYASHA FLORENCE MURERIWA 0604748V Supervisor: Dr Elhadi Adam A dissertation submitted to the School of Geography, Archaeology and Environmental Studies, Faculty of Science, University of the Witwatersrand in fulfilment of the academic requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Environmental Sciences March 2016 Johannesburg South Africa Abstract Decades after the first introduction of the Prosopis spp. (mesquite) to South Africa in the late 1800s for its benefits, the invasive nature of the species became apparent as its spread in regions of South Africa resulting in devastating effects to biodiversity, ecosystems and the socio- economic wellbeing of affected regions. Various control and management practices that include biological, physical, chemical and integrated methods have been tested with minimal success as compared to the rapid spread of the species. From previous studies, it has been noted that one of the reasons for the low success rates in mesquite control and management is a lack of sufficient information on the species invasion dynamic in relation to its very similar co-existing species. In order to bridge this gap in knowledge, vegetation species mapping techniques that use remote sensing methods need to be tested for the monitoring, detection and mapping of the species spread. Unlike traditional field survey methods, remote sensing techniques are better at monitoring vegetation as they can cover very large areas and are time-effective and cost- effective. Thus, the aim of this research was to examine the possibility of mapping and spectrally discriminating Prosopis glandulosa from its native co-existing species in semi-arid parts of South Africa using remote sensing methods. -

Taxonomic Revision of Genus Prosopis L. in Egypt

International Journal of Environment Volume : 04 | Issue : 01 | Jan-Mar. | 2015 ISSN: 2077-4508 Pages: 13-20 Taxonomic revision of genus Prosopis L. in Egypt Abd El Halim A. Mohamed and Safwat A. Azer Flora and Phytotaxonomy Researches Department, Horticultural Research Institute, Agricultural Research Center, Dokki, Giza, Egypt ABSTRACT The aim of this work was to survey the new record invasive alien Prosopis juliflora and clarifies the taxonomic relationships among genus Prosopis L. in Egypt. The wild species are Prosopis farcta (Banks & Sol.) Macbride and Prosopis juliflora (Sw.) DC. The cultivated species are Prosopis cineraria (L.) Druce; Prosopis glandulosa Torr. and Prosopis strombulifera (Lam.) Benth. Based on morphological traits, the numerical analysis divided the Prosopis species into three clusters. Cluster one included: Prosopis glandulosa and Prosopis juliflora. Cluster two included: Prosopis farcta and Prosopis cineraria. Cluster three included: Prosopis strombulifera. According to the degree of similarity, the species of cluster one had the highest ratio (75%) followed by (55.6%) between the species of cluster two. Moreover, the highest ratio (33.3%) was recorded between Prosopis strombulifera and Prosopis juliflora, while the lowest ratio (20.8%) was recorded between Prosopis strombulifera and Prosopis cineraria. This work recoded Prosopis juliflora to the Flora of Egypt. Key words: Taxonomy, Prosopis, alien species, numerical analysis, similarity level, Egypt. Introduction The genus Prosopis L. belongs to the family Leguminosae, subfamily Mimosoideae, tribe Mimosae (Burkart, 1976; Sherry et al., 2011). It comprises 44 species and five sections based on observed morphological differences among studied taxa (Burkart, 1976). The five sections included: Prosopis; Anonychium; Strombocarpa; Monilicarpa and Algarobia (Burkart, 1976; Landeras et al., 2004; Elmeer and Almalki, 2011). -

The Prosopis Juliflora - Prosopis Pallida Complex: a Monograph

DFID DFID Natural Resources Systems Programme The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph NM Pasiecznik With contributions from P Felker, PJC Harris, LN Harsh, G Cruz JC Tewari, K Cadoret and LJ Maldonado HDRA - the organic organisation The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph NM Pasiecznik With contributions from P Felker, PJC Harris, LN Harsh, G Cruz JC Tewari, K Cadoret and LJ Maldonado HDRA Coventry UK 2001 organic organisation i The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph Correct citation Pasiecznik, N.M., Felker, P., Harris, P.J.C., Harsh, L.N., Cruz, G., Tewari, J.C., Cadoret, K. and Maldonado, L.J. (2001) The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph. HDRA, Coventry, UK. pp.172. ISBN: 0 905343 30 1 Associated publications Cadoret, K., Pasiecznik, N.M. and Harris, P.J.C. (2000) The Genus Prosopis: A Reference Database (Version 1.0): CD ROM. HDRA, Coventry, UK. ISBN 0 905343 28 X. Tewari, J.C., Harris, P.J.C, Harsh, L.N., Cadoret, K. and Pasiecznik, N.M. (2000) Managing Prosopis juliflora (Vilayati babul): A Technical Manual. CAZRI, Jodhpur, India and HDRA, Coventry, UK. 96p. ISBN 0 905343 27 1. This publication is an output from a research project funded by the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of developing countries. The views expressed are not necessarily those of DFID. (R7295) Forestry Research Programme. Copies of this, and associated publications are available free to people and organisations in countries eligible for UK aid, and at cost price to others. Copyright restrictions exist on the reproduction of all or part of the monograph. -

Seed Germination and Early Seedling Survival of the Invasive Species Prosopis Juliflora (Fabaceae) Depend on Habitat and Seed Dispersal Mode in the Caatinga Dry Forest

Seed germination and early seedling survival of the invasive species Prosopis juliflora (Fabaceae) depend on habitat and seed dispersal mode in the Caatinga dry forest Clóvis Eduardo de Souza Nascimento1,2, Carlos Alberto Domingues da Silva3,4, Inara Roberta Leal5, Wagner de Souza Tavares6, José Eduardo Serrão7, José Cola Zanuncio8 and Marcelo Tabarelli5 1 Centro de Pesquisa Agropecuária do Trópico Semi-Árido, Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária, Petrolina, Pernambuco, Brasil 2 Departamento de Ciências Humanas, Universidade do Estado da Bahia, Juazeiro, Bahia, Brasil 3 Centro Nacional de Pesquisa de Algodão, Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária, Campina Grande, Paraíba, Brasil 4 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Agrárias, Universidade Estadual da Paraíba, Campina Grande, Paraíba, Brasil 5 Departamento de Botânica, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife, Pernambuco, Brasil 6 Asia Pacific Resources International Holdings Ltd. (APRIL), PT. Riau Andalan Pulp and Paper (RAPP), Pangkalan Kerinci, Riau, Indonesia 7 Departamento de Biologia Geral, Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Viçosa, Minas Gerais, Brasil 8 Departamento de Entomologia/BIOAGRO, Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Viçosa, Minas Gerais, Brasil ABSTRACT Background: Biological invasion is one of the main threats to tropical biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Prosopis juliflora (Sw) DC. (Fabales: Fabaceae: Caesalpinioideae) was introduced in the Caatinga dry forest of Northeast Brazil at early 1940s and successfully spread across the region. As other invasive species, it may benefit from the soils and seed dispersal by livestock. Here we examine how seed Submitted 22 November 2018 Accepted 5 July 2020 dispersal ecology and soil conditions collectively affect seed germination, early Published 3 September 2020 seedling performance and consequently the P. -

A Case Study on the Potential of the Multipurpose Prosopis Tree

23 Underutilised crops for famine and poverty alleviation: a case study on the potential of the multipurpose Prosopis tree N.M. Pasiecznik, S.K. Choge, A.B. Rosenfeld and P.J.C. Harris In its native Latin America, the Prosopis tree (also known as Mesquite) has multiple uses as a fuel wood, timber, charcoal, animal fodder and human food. It is also highly drought-resistant, growing under conditions where little else will survive. For this reason, it has been introduced as a pioneer species into the drylands of Africa and Asia over the last two centuries as a means of reclaiming desert lands. However, the knowledge of its uses was not transferred with it, and left in an unmanaged state it has developed into a highly invasive species, where it encroaches on farm land as an impenetrable, thorny thicket. Attempts to eradicate it are proving costly and largely unsuccessful. In 2006, the problem of Prosopis was hitting the headlines on an almost weekly basis in Kenya. Yet amidst calls for its eradication, a pioneering team from the Kenya Forestry Research Institute (KEFRI) and HDRA’s International Programme set out to demonstrate its positive uses. Through a pilot training and capacity building programme in two villages in Baringo District, people living with this tree learned for the first time how to manage and use it to their benefit, both for food security and income generation. Results showed that the pods, milled to flour, would provide a crucial, nutritious food supplement in these famine-prone desert margins. The pods were also used or sold as animal fodder, with the first international order coming from South Africa by the end of the year. -

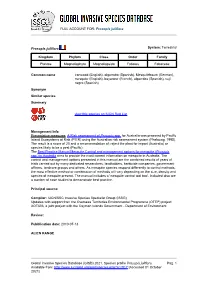

Prosopis Juliflora Global Invasive Species Database (GISD)

FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Prosopis juliflora Prosopis juliflora System: Terrestrial Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Plantae Magnoliophyta Magnoliopsida Fabales Fabaceae Common name ironwood (English), algarrobo (Spanish), Mesquitebaum (German), mesquite (English), bayarone (French), algarroba (Spanish), cují negro (Spanish) Synonym Similar species Summary view this species on IUCN Red List Management Info Preventative measures: A Risk assessment of Prosopis spp. for Australia was prepared by Pacific Island Ecosystems at Risk (PIER) using the Australian risk assessment system (Pheloung, 1995). The result is a score of 20 and a recommendation of: reject the plant for import (Australia) or species likely to be a pest (Pacific). The Best Practice Manual Mesquite Control and management options for mesquite (Prosopis spp.) in Australia aims to provide the most current information on mesquite in Australia. The control and management options presented in this manual are the combined results of years of trials carried out by many dedicated researchers, landholders, herbicide companies, government officers, landcare groups and others. As mesquite species respond differently to control methods, the most effective method or combination of methods will vary depending on the size, density and species of mesquite present. The manual includes a 'mesquite control tool box'. Included also are a number of case studies to demonstrate best practice. Principal source: Compiler: IUCN/SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG) Updates with support from the Overseas -

Prosopis Pallida) and Implications for Peruvian Dry Forest Conservation

Revista de Ciencias Ambientales (Trop J Environ Sci). (Enero-Junio, 2018). EISSN: 2215-3896. Vol 52(1): 49-70. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15359/rca.52-1.3 URL: www.revistas.una.ac.cr/ambientales EMAIL: [email protected] Community Use and Knowledge of Algarrobo (Prosopis pallida) and Implications for Peruvian Dry Forest Conservation Uso y conocimiento comunitario del algarrobo (Prosopis pallida) e implicaciones para la conservación del bosque seco peruano Johanna Depenthala and Laura S. Meitzner Yoderb a Master’s candidate in Environmental Management with a concentration in Ecosystem Science and Conservation at Duke University; ORCID: 0000-0003-4560-0862, [email protected] b Doctorate in Forestry and Environmental Studies; researcher and professor at Wheaton College, IL, [email protected] Director y Editor: Dr. Sergio A. Molina-Murillo Consejo Editorial: Dra. Mónica Araya, Costa Rica Limpia, Costa Rica Dr. Gerardo Ávalos-Rodríguez. SFS y UCR, USA y Costa Rica Dr. Manuel Guariguata. CIFOR-Perú Dr. Luko Hilje, CATIE, Costa Rica Dr. Arturo Sánchez Azofeifa. Universidad de Alberta-Canadá Asistente: Sharon Rodríguez-Brenes Editorial: Editorial de la Universidad Nacional de Costa Rica (EUNA) Los artículos publicados se distribuye bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución 4.0 Internacional (CC BY 4.0) basada en una obra en http://www. revistas.una.ac.cr/ambientales., lo que implica la posibilidad de que los lectores puedan de forma gratuita descargar, almacenar, copiar y distribuir la versión final aprobada y publicada del artículo, siempre y cuando se mencione la fuente y autoría de la obra. Revista de Ciencias Ambientales (Trop J Environ Sci). -

Defoliation and Woody Plant (Shape Prosopis Glandulosa) Seedling

Plant Ecology 138: 127–135, 1998. 127 © 1998 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands. Defoliation and woody plant (Prosopis glandulosa) seedling regeneration: potential vs realized herbivory tolerance Jake F. Weltzin1, Steven R. Archer & Rodney K. Heitschmidt2 Department of Rangeland Ecology and Management, Texas A & M University, College Station, TX 77843–2126, USA; 1Corresponding author: Department of Biological Sciences, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 46556, USA; 2USDA/ARS Ft. Keogh, Rt. 1, Box 2021, Miles City, MT 59301, USA Received 27 March 1997; accepted in revised form 27 April 1998 Key words: Browsing, Clipping, Competition, Honey mesquite, Survival, Texas, Top removal Abstract Herbivory by rodents, lagomorphs and insects may locally constrain woody plant seedling establishment and stand development. Recruitment may therefore depend either upon plant tolerance of herbivory, or low herbivore abundance, during seedling establishment. We tested potential herbivory tolerance by quantifying growth, biomass allocation, and survival of defoliated Prosopis glandulosa seedlings under optimal abiotic conditions in the absence of competition. Realized tolerance was assessed by clipping seedlings of known age grown in the field with and without herbaceous competition. At 18-d (D ‘young’) or 33-d (D ‘old’) of age, seedlings in the growth chamber were clipped just above the first (cotyledonary) node, above the fourth node, or were retained as non-clipped controls. Potential tolerance to defoliation was high and neither cohort showed evidence of meristematic limitations to regeneration. Clipping markedly reduced biomass production relative to controls, especially belowground, but survival of seedlings de- foliated 5 times was still ≥75%. Contrary to expectations, survival of seedlings defoliated above the cotyledonary node 10 times was greater (P<0:10) for ‘young’ (75%) than ‘old’ (38%) seedlings. -

Climate-Ready Tree List

Location Type 1 - Small Green Stormwater Infrastructure (GSI) Features Location Characteristics Follows “Right Tree in the Right Place” Low Points Collect Stormwater Runoff Soil Decompacted to a Depth ≥ 18” May Have Tree Trenches, Curb Cuts, or Scuppers Similar Restrictions to Location Type 5 Examples:Anthea Building, SSCAFCA, and South 2nd St. Tree Characteristics Recommended Trees Mature Tree Height: Site Specific Celtis reticulata Netleaf Hackberry Inundation Compatible up to 96 Hours. Cercis canadensis var. mexicana* Mexican Redbud* Cercis occidentalis* Western Redbud* Pollution Tolerant Cercis reniformis* Oklahoma Redbud* Cercis canadensis var. texensis* Texas Redbud* Crataegus ambigua* Russian Hawthorne* Forestiera neomexicana New Mexico Privet Fraxinus cuspidata* Fragrant Ash* Lagerstroemia indica* Crape Myrtle* Pistacia chinensis Chines Pistache Prosopis glandulosa* Honey Mesquite* Prosopis pubescens* Screwbean Mesquite* Salix gooddingii Gooding’s Willow Sapindus saponaria var. drummondii* Western Soapberry* * These species have further site specific needs found in Master List Photo Credit: Land andWater Summit ClimateReady Trees - Guidelines for Tree Species Selection in Albuquerque’s Metro Area 26 Location Type 2 - Large Green Stormwater Infrastructure (GSI) Features Location Characteristics Follows “Right Tree in the Right Place” Low Points Collect Stormwater Runoff Soil Decompacted to a Depth ≥ 18” May Have Basins, Swales, or Infiltration Trenches Examples: SSCAFCA landscaping, Pete Domenici Courthouse, and Smith Brasher Hall -

Invasion of Prosopis Juliflora and Local Livelihoods Case Study from the Lake Baringo Area of Kenya

Invasion of prosopis juliflora and local livelihoods Case study from the Lake Baringo area of Kenya Esther Mwangi and Brent Swallow Invasion of prosopis juliflora and local livelihoods: Case study from the Lake Baringo area of Kenya Esther Mwangi and Brent Swallow World Agroforestry Centre 2 LIMITED CIRCULATION Titles in the Working Paper Series aim to disseminate interim results on agroforestry research and practices and stimulate feedback from the scientific community. Other publication series from the World Agroforestry Centre include: Agroforestry Perspectives, Technical Manuals and Occasional Papers. Correct citation: Esther Mwangi & Brent Swallow, June 2005, Invasion of Prosopis juliflora and local livelihoods: Case study from the lake Baringo area of Kenya. ICRAF Working Paper – no. 3. Nairobi: World Agroforestry Centre Published by the World Agroforestry Centre Environmental Services Theme United Nations Avenue PO Box 30677, GPO 00100 Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254(0)20 7224000, via USA +1 650 833 6645 Fax: +254(0)20 7224001, via USA +1 650 833 6646 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.worldagroforestry.org © World Agroforestry Centre 2005 ICRAF Working Paper no. 3 The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the World Agroforestry Centre. Articles appearing in this publication may be quoted or reproduced without charge, provided the source is acknowledged. No use of this publication may be made for resale or other commercial purposes. All images remain the sole property of their source and may not be used for any purpose without written permission of the author. The geographic designation employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Agroforestry Centre concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

The Good, the Bad and the Thorny: Impacts of Prosopis in Africa

The Good, the Bad and the Thorny: Impacts of Prosopis in Africa Nick Pasiecznik CAB International, Wallingford, OXON, UK. E-mail: [email protected] April 2004 Tropical agroforesters have been successful over the past 25 years in the selection, introduction, promotion and plantation of many exotic, fast-growing tree species for the benefit of rural people. However, some of these ‘miracle trees’ have proved to be very well adapted to local conditions, escaping from cultivation and spreading widely as aggressive weeds, threatening, rather than improving livelihoods. The status of exotic Prosopis species in sub-Saharan Africa epitomises this dilemma; it is the main plantation species in Cape Verde, the subject of national eradication and control programmes in South Africa, and all possible combinations in between, throughout the Sahel, East and southern Africa. Even after decades of work with probably the most common and widespread, multi-purpose trees in Africa, it appears that the agroforestry research and development community still cannot decide what to advise. Perceptions of Prosopis species vary widely, ranging from the most useful and productive tree tolerant of sites where little else will grow, to a weedy invader worthy only of wholesale eradication. What is a weed to one farmer may be a source of livelihood to another, but the extent of this dichotomy of opinion regarding Prosopis sends a very confused message to extension workers, foresters and farmers, who don’t know whether to plant it, prune it or pull it up. Prosopis trees provided many valuable resources to indigenous populations in the native range, and are still a source of food, feed, fuel, timber and other raw materials today; often the cornerstone of local economies in arid regions where they constitute the main forest resource.