Blake's "Tender Stranger": Thel and Hervey's Meditations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Checklist of Publications and Discoveries in 2013

ARTICLE Part II: Reproductions of Drawings and Paintings Section A: Illustrations of Individual Authors Section B: Collections and Selections Part III: Commercial Engravings Section A: Illustrations of Individual Authors William Blake and His Circle: Part IV: Catalogues and Bibliographies A Checklist of Publications and Section A: Individual Catalogues Section B: Collections and Selections Discoveries in 2013 Part V: Books Owned by William Blake the Poet Part VI: Criticism, Biography, and Scholarly Studies By G. E. Bentley, Jr. Division II: Blake’s Circle Blake Publications and Discoveries in 2013 with the assistance of Hikari Sato for Japanese publications and of Fernando 1 The checklist of Blake publications recorded in 2013 in- Castanedo for Spanish publications cludes works in French, German, Japanese, Russian, Span- ish, and Ukrainian, and there are doctoral dissertations G. E. Bentley, Jr. ([email protected]) is try- from Birmingham, Cambridge, City University of New ing to learn how to recognize the many styles of hand- York, Florida State, Hiroshima, Maryland, Northwestern, writing of a professional calligrapher like Blake, who Oxford, Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, Voronezh used four distinct hands in The Four Zoas. State, and Wrocław. The Folio Society facsimile of Blake’s designs for Gray’s Poems and the detailed records of “Sale Editors’ notes: Catalogues of Blake’s Works 1791-2013” are likely to prove The invaluable Bentley checklist has grown to the point to be among the most lastingly valuable of the works listed. where we are unable to publish it in its entirety. All the material will be incorporated into the cumulative Gallica “William Blake and His Circle” and “Sale Catalogues of William Blake’s Works” on the Bentley Blake Collection 2 A wonderful resource new to me is Gallica <http://gallica. -

Issues) and Begin with the Summer Issue

VOLUME 22 NUMBER 3 WINTER 1988/89 ■iiB ii ••▼•• w BLAKE/AN ILLUSTRATED QUARTERLY WINTER 1988/89 REVIEWS 103 William Blake, An Island in the Moon: A Facsimile of the Manuscript Introduced, Transcribed, and Annotated by Michael Phillips, reviewed by G. E. Bentley, Jr. 105 David Bindman, ed., William Blake's Illustrations to the Book of Job, and Colour Versions of William- Blake 's Book of job Designs from the Circle of John Linnell, reviewed by Martin Butlin AN ILLUSTRATED QUARTERLY VOLUME 22 NUMBER 3 WINTER 1988/89 DISCUSSION 110 An Island in the Moon CONTENTS Michael Phillips 80 Canterbury Revisited: The Blake-Cromek Controversy by Aileen Ward CONTRIBUTORS 93 The Shifting Characterization of Tharmas and Enion in Pages 3-7 of Blake's Vala or The FourZoas G. E. BENTLEY, JR., University of Toronto, will be at by John B. Pierce the Department of English, University of Hyderabad, India, through November 1988, and at the National Li• brary of Australia, Canberra, from January-April 1989. Blake Books Supplement is forthcoming. MARTIN BUTLIN is Keeper of the Historic British Col• lection at the Tate Gallery in London and author of The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake (Yale, 1981). MICHAEL PHILLIPS teaches English literature at Edinburgh University. A monograph on the creation in J rrfHRurtfr** fW^F *rWr i*# manuscript and "Illuminated Printing" of the Songs of Innocence and Songs ofExperience is to be published in 1989 by the College de France. JOHN B. PIERCE, Assistant Professor in English at the University of Toronto, is currently at work on the manu• script of The Four Zoas. -

How the Tomb Becomes a Womb by Eric Howell

© 2013 Center for Christian Ethics at Baylor University 11 How the Tomb Becomes a Womb BY ERIC HOWELL By baptism “you died and were born,” a fourth-century catechism teaches. “The saving water was your tomb and at the same time a womb.” When we are born to new life in those ‘maternal waters,’ we celebrate and receive grace that shapes how we live and die. ollowing an extended argument in which the grace given to us through Christ is set over against the sinful nature we inherit from Adam, the FApostle Paul asks: “What shall we say then?” (Romans 6:1, ESV)1 and the implied answer is clear: grace wins. This is especially clear in the crescendo of his argument: “but where sin increased, grace abounded all the more, so that, as sin reigned in death, grace also might reign through righteousness leading to eternal life through Jesus Christ our Lord” (5:20b-21, ESV). Immediately Paul recognizes that his argument sets a dangerous theological trap to be sprung. He must now disarm the derivation from his premise of a devious conclusion: namely, since more sin equals more grace, therefore, sin more! Before the trap can be sprung, Paul spins on the point and asks, “What shall we say then? Are we to continue in sin that grace may abound?” (6:1, ESV) No way! How can we who died to sin still live in it? For Paul, the gift of God’s grace is an invitation to a new way of life, a radical discipleship to Jesus Christ that puts to death the old life and gives birth to new life. -

Alicia Ostriker, Ed., William Blake: the Complete Poems

REVIEW Alicia Ostriker, ed., William Blake: The Complete Poems John Kilgore Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 12, Issue 4, Spring 1979, pp. 268-270 268 psychological—carried by Turner's sublimely because I find myself in partial disagreement with overwhelming sun/god/king/father. And Paulson argues Arnheim's contention "that any organized entity, in that the vortex structure within which this sun order to be grasped as a whole by the mind, must be characteristically appears grows as much out of translated into the synoptic condition of space." verbal signs and ideas ("turner"'s name, his barber- Arnheim seems to believe, not only that all memory father's whorled pole) as out of Turner's early images of temporal experiences are spatial, but that sketches of vortically copulating bodies. Paulson's they are also synoptic, i.e. instantaneously psychoanalytical speculations are carried to an perceptible as a comprehensive whole. I would like extreme by R. F. Storch who argues, somewhat to suggest instead that all spatial images, however simplistically, that Shelley's and Turner's static and complete as objects, are experienced tendencies to abstraction can be equated with an temporally by the human mind. In other works, we alternation between aggression toward women and a "read" a painting or piece of sculpture or building dream-fantasy of total love. Storch then applauds in much the same way as we read a page. After Constable's and Wordsworth's "sobriety" at the isolating the object to be read, we begin at the expense of Shelley's and Turner's overly upper left, move our eyes across and down the object; dissociated object-relations, a position that many when this scanning process is complete, we return to will find controversial. -

Protective Pastoral: Innocence and Female Experience in William Blake's Songs and Christina Rossetti's Goblin Market June Sturrock

Colby Quarterly Volume 30 Article 4 Issue 2 June June 1994 Protective Pastoral: Innocence and Female Experience in William Blake's Songs and Christina Rossetti's Goblin Market June Sturrock Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 30, no.2, June 1994, p.98-108 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sturrock: Protective Pastoral: Innocence and Female Experience in William B Protective Pastoral: Innocence and Female Experience in William Blake's Songs and Christina Rossetti's Goblin Market by JlTNE STURROCK IIyEA, THOUGH I walk through the valley ofthe shadow ofdeath, I shall fear no evil, for thou art with me, thy rod and thy staffthey comfort me." The twenty-third psalm has been offered as comfort to the sick and the grieving for thousands ofyears now, with its image ofGod as the good shepherd and the soul beloved ofGod as the protected sheep. This psalm, and such equally well-known passages as Isaiah's "He shall feed his flock as a shepherd: he shall gather the lambs in his arms" (40. 11), together with the specifically Christian version: "I am the good shepherd" (John 10. 11, 14), have obviously affected the whole pastoral tradition in European literature. Among othereffects the conceptofGod as shepherd has allowed for development of the protective implications of classical pastoral. The pastoral idyll-as opposed to the pastoral elegy suggests a safe, rural world in that corruption, confusion and danger are placed elsewhere-in the city. -

The Visionary Company

WILLIAM BLAKE 49 rible world offering no compensations for such denial, The] can bear reality no longer and with a shriek flees back "unhinder' d" into her paradise. It will turn in time into a dungeon of Ulro for her, by the law of Blake's dialectic, for "where man is not, nature is barren"and The] has refused to become man. The pleasures of reading The Book of Thel, once the poem is understood, are very nearly unique among the pleasures of litera ture. Though the poem ends in voluntary negation, its tone until the vehement last section is a technical triumph over the problem of depicting a Beulah world in which all contraries are equally true. Thel's world is precariously beautiful; one false phrase and its looking-glass reality would be shattered, yet Blake's diction re mains firm even as he sets forth a vision of fragility. Had Thel been able to maintain herself in Experience, she might have re covered Innocence within it. The poem's last plate shows a serpent guided by three children who ride upon him, as a final emblem of sexual Generation tamed by the Innocent vision. The mood of the poem culminates in regret, which the poem's earlier tone prophe sied. VISIONS OF THE DAUGHTERS OF ALBION The heroine of Visions of the Daughters of Albion ( 1793), Oothoon, is the redemption of the timid virgin Thel. Thel's final griefwas only pathetic, and her failure of will a doom to vegetative self-absorption. Oothoon's fate has the dignity of the tragic. -

Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in the Four Zoas

Colby Quarterly Volume 19 Issue 4 December Article 3 December 1983 Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in The Four Zoas Michael Ackland Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 19, no.4, December 1983, p.173-189 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Ackland: Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in The Four Zoas Blake's Critique of Enlightenment Reason in The Four Zoas by MICHAEL ACKLAND RIZEN is at once one of Blake's most easily recognizable characters U and one of his most elusive. Pictured often as a grey, stern, hover ing eminence, his wide-outspread arms suggest oppression, stultifica tion, and limitation. He is the cruel, jealous patriarch of this world, the Nobodaddy-boogey man-god evoked to quieten the child, to still the rabble, to repress the questing intellect. At other times in Blake's evolv ing mythology he is an inferior demiurge, responsible for this botched and fallen creation. In political terms, he can project the repressive, warmongering spirit of Pitt's England, or the collective forces of social tyranny. More fundamentally, he is a personal attribute: nobody's daddy because everyone creates him. As one possible derivation of his name suggests, he is "your horizon," or those impulses in each of us which, through their falsely assumed authority, limit all man's other capabilities. Yet Urizen can, at times, earn our grudging admiration. -

The Poetry of Rita Dove

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Winter 1999 Language's "bliss of unfolding" in and through history, autobiography and myth: The poetry of Rita Dove Carol Keyes University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Keyes, Carol, "Language's "bliss of unfolding" in and through history, autobiography and myth: The poetry of Rita Dove" (1999). Doctoral Dissertations. 2107. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/2107 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMi films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

New Risen from the Grave: Nineteen Unknown Watercolors by William Blake

ARTICLE New Risen from the Grave: Nineteen Unknown Watercolors by William Blake Martin Butlin Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 35, Issue 3, Winter 2002, pp. 68-73 Cromek. Suffice it to say that John Flaxman, in a letter of 18 ARTICLES October 1805, wrote that "Mr. Cromak has employed Blake to make a set of 40 drawings from Blair's poem of the Grave New Risen from the Grave: 20 of which he proposes [to] have engraved by the Designer ..." (Bentley (2001) 279). Blake himself, in a letter to Will- Nineteen Unknown Watercolors iam Hayley of 27 November 1805, wrote that about two by William Blake months earlier "my Friend Cromek" had come "to me de- siring to have some of my Designs, he namd his Price & wishd me to Produce him Illustrations to The Grave A Poem BY MARTIN BUTLIN by Robert Blair, in consequence of this I produced about twenty Designs which pleasd so well that he with the same hat is certainly the most exciting Blake discovery since liberality with which he set me about the Drawings, has now WI began work on the artist, and arguably the most set me to Engrave them."2 Cromek, in the first version of important since Blake began to be appreciated in the sec- his Prospectus, dated November 1805, advertised "A NEW AND ond half of the nineteenth century, started in a deceptively ELEGANT EDITION OF BLAIR'S GRAVE, ILLUSTRATED WITH FIFTEEN low-key way. A finished watercolor for the engraving of "The PRINTS FROM DESIGNS INVENTED AND TO BE ENGAVED BY WILLIAM Soul Hovering over the Body," published in Robert Cromek's BLAKE .. -

The Bravery of William Blake

ARTICLE The Bravery of William Blake David V. Erdman Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 10, Issue 1, Summer 1976, pp. 27-31 27 DAVID V. ERDMAN The Bravery of William Blake William Blake was born in the middle of London By the time Blake was eighteen he had been eighteen years before the American Revolution. an engraver's apprentice for three years and had Precociously imaginative and an omnivorous reader, been assigned by his master, James Basire, to he was sent to no school but a school of drawing, assist in illustrating an antiquarian book of at ten. At fourteen he was apprenticed as an Sepulchral Monuments in Great Britain. Basire engraver. He had already begun writing the sent Blake into churches and churchyards but exquisite lyrics of Poetioal Sketches (privately especially among the tombs in Westminster Abbey printed in 1783), and it is evident that he had to draw careful copies of the brazen effigies of filled his mind and his mind's eye with the poetry kings and queens, warriors and bishops. From the and art of the Renaissance. Collecting prints of drawings line engravings were made under the the famous painters of the Continent, he was happy supervision of and doubtless with finishing later to say that "from Earliest Childhood" he had touches by Basire, who signed them. Blake's dwelt among the great spiritual artists: "I Saw & longing to make his own original inventions Knew immediately the difference between Rafael and (designs) and to have entire charge of their Rubens." etching and engraving was yery strong when it emerged in his adult years. -

William Blake 1 William Blake

William Blake 1 William Blake William Blake William Blake in a portrait by Thomas Phillips (1807) Born 28 November 1757 London, England Died 12 August 1827 (aged 69) London, England Occupation Poet, painter, printmaker Genres Visionary, poetry Literary Romanticism movement Notable work(s) Songs of Innocence and of Experience, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, The Four Zoas, Jerusalem, Milton a Poem, And did those feet in ancient time Spouse(s) Catherine Blake (1782–1827) Signature William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his lifetime, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual arts of the Romantic Age. His prophetic poetry has been said to form "what is in proportion to its merits the least read body of poetry in the English language".[1] His visual artistry led one contemporary art critic to proclaim him "far and away the greatest artist Britain has ever produced".[2] In 2002, Blake was placed at number 38 in the BBC's poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.[3] Although he lived in London his entire life except for three years spent in Felpham[4] he produced a diverse and symbolically rich corpus, which embraced the imagination as "the body of God",[5] or "Human existence itself".[6] Considered mad by contemporaries for his idiosyncratic views, Blake is held in high regard by later critics for his expressiveness and creativity, and for the philosophical and mystical undercurrents within his work. His paintings William Blake 2 and poetry have been characterised as part of the Romantic movement and "Pre-Romantic",[7] for its large appearance in the 18th century. -

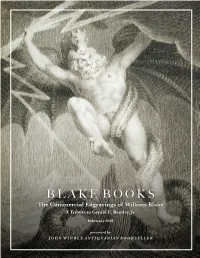

Blake Books, Contributed Immeasurably to the Understanding and Appreciation of the Enormous Range of Blake’S Works

B L A K E B O O K S The Commercial Engravings of William Blake A Tribute to Gerald E. Bentley, Jr. February 2018 presented by J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y B L A K E B O O K S The Commercial Engravings of William Blake A Tribute to Gerald E. Bentley, Jr. February 2018 Blake is best known today for his independent vision and experimental methods, yet he made his living as a commercial illustrator. This exhibition shines a light on those commissioned illustrations and the surprising range of books in which they appeared. In them we see his extraordinary versatility as an artist but also flashes of his visionary self—flashes not always appreciated by his publishers. On display are the books themselves, objects that are far less familiar to his admirers today, but that have much to say about Blake the artist. The exhibition is a small tribute to Gerald E. Bentley, Jr. (1930 – 2017), whose scholarship, including the monumental bibliography, Blake Books, contributed immeasurably to the understanding and appreciation of the enormous range of Blake’s works. J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 205, San Francisco, CA 94108 www.williamblakegallery.com www.johnwindle.com 415-986-5826 - 2 - B L A K E B O O K S : C O M M E R C I A L I L L U S T R A T I O N Allen, Charles.