Shifting Gears: How a Stronger Union Could

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Armstrong.Pdf

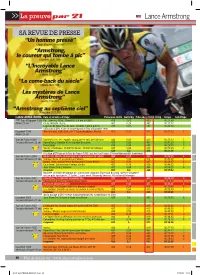

>> La preuve par 21 Lance Armstrong SA REVUE DE PRESSE “Un homme pressé” L’Equipe Magazine, 04.09.1993 “Armstrong, le coureur qui tombe à pic” L’Humanité, 05.07.1999 “L’Incroyable Lance Armstrong” L’Equipe, 12.07.1999 “Le come-back du siècle” L’Equipe, 26.07.1999 “Les mystères de Lance Armstrong” Le JDD, 27.06.2004 “Armstrong au septième ciel” Le Midi Libre, 25.07.2005 Lance ARMSTRONG Cols et victoires d’étape Puissance réelle watts/kg Puissance étalon 78 kg temps Cols Etape Tour Tour d’Espagne 1998 Pal. Jimenez 433w, 20min30s, 8,4 km à 6,49%, 418 5,65 400 00:21:49 4ème-27 ans Cerler. Montée courte. 462 6,24 442 00:11:33 Lagunas de Neila. Peu de vent, en forêt, 7 km à 8,57%, 415 5,61 397 00:22:18 Utilisation d’EPO et de cortisone durant le Tour d’Espagne 1998 Dauphiné 1999 Mont Ventoux CLM. ‘Battu de 1’1s par Vaughters. Record. 455 6,15 432 00:57:52 1 8ème-28 ans Tour de France 2004 La Mongie. 2ème derrière Basso 487 6,58 462 00:23:15 2 Tour de France 1999 Sestrières 1er. 1er «exploit» marquant en solo. Vent de face 448 6,05 420 00:27:13 5 1er puis déclassé-33 ans Beille 1er. En solitaire. 438 5,92 416 00:45:40 6 1er puis déclassé-28 ans Alpe d’Huez. Contrôle et se contente de suivre. 436 5,89 407 00:41:20 3 Chalimont 1er. Victoire à Villard de Lans 410 5,54 392 00:19:05 3 Piau Engaly 395 5,34 385 00:26:15 5 Alpe d’Huez CLM 1er. -

AG2R LA MONDIALE Press Release

28 MAR, 2017 AG2R LA MONDIALE AND FACTOR BIKES TRAVEL WITH SCICON® BAGS Leading French team AG2R La Mondiale is the latest WorldTour outfit to put its trust in SCICON® Bags for their travelling needs, to safely transport their Factor Bikes around the world for a busy, international race calendar. The team’s Factor Bikes will be housed in a range of custom SCICON® AeroComfort ROAD 3.0 TSA Bike Travel Bags this season, including that of last year’s Tour de France runner up, Romain Bardet. “Our partnership with AG2R La Mondiale is a strong relationship to extend out reach in the French market, and it also sees more Grand Tour contenders travelling with SCICON® Bags. It’s also a strong connection between the Factor bike brand, an exciting, new brand to the market that we’re pleased to be working with.” Christian Pearce SCICON® Brand Manager "The SCICON® Bags are very functional bike bags with a well designed interior fixing system. The robustness of the fabric and the integrated wheels make this product very practical for travelling with. Above all, these bags do not require any disassembly of the handlebar, the seatpost or the rear derailleur. It’s a significant time saver in our busy racing and travel calendar.” Marc Accard Team’s Mechanic As a WorldTour team, AG2R La Mondiale will compete at all three Grand Tours this season, having already travelled to Australia, Oman, Abu Dhabi and to several European locations already in the first three months of the year. MEDIA CONTACT DOWNLOAD MEDIA FOLLOW US Francesca Bonan Click here to download [email protected] the digital assets #BRINGYOURBIKE | MEDIA ARCHIVE | NEWS.SCICONBAGS.COM | SCICONBAGS.COM AEROCOMFORT ROAD 3.0 TSA BIKE TRAVEL BAG TRAVEL LIKE A PRO SCICON® presents an update of one of its icons: the AeroComfort ROAD 3.0 TSA bike travel bag. -

P16 Layout 1 2/17/15 9:13 PM Page 1

p16_Layout 1 2/17/15 9:13 PM Page 1 WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 18, 2015 SPORTS FIS head laments drop in recreational skiers BEAVER CREEK: Sitting on a terrace on Colorado resorts of Vail/Beaver Creek come from their ski-mad nation. lost at the current rate. It is trend right champions the worlds were viewed as a a bluebird day overlooking the Birds of were projected to provide a $130 mil- But the numbers Kasper and other across Europe’s alpine arc with the sport chance to put skiing in the American Prey finish line, International Ski lion two-week jolt to the local economy. industry leaders are fixated on are the gaining ground in some areas and los- sporting spotlight. Gold medal perform- Federation (FIS) chief Gian Franco As advertised, the event delivered plen- participation figures that will ultimately ing traction in others. ances from Ted Ligety in the giant Kasper scanned the horizon for recre- ty of thrills and spills on the slopes and impact the FIS portfolio of world cham- “What is most interesting is the num- slalom and 19-year-old ski darling ational skiers that never appear. “Even in an adequate apres-ski buzz in Vail but pionships: alpine, nordic, freestyle, ber of new nations that are now becom- Mikaela Shiffrin were dramatic. the cold countries like Switzerland and for a large part was greeted with a snowboard and ski jumping. ing active within skiing, as an example But with the championships sand- Austria the number of kids being shrug. we now have Kazakhstan who are now wiched between the Super Bowl and involved in skiing goes down,” Kasper Vacancy signs flashed at hotels and LOSING TRACTION bidding for the Olympic Games,” said FIS the NBA All-Star weekend and qualify- told Reuters during a piste-side inter- resorts around the Vail valley while A federation that relies on snow as its general secretary Sarah Lewis. -

Spitting in the Soup Mark Johnson

SPITTING IN THE SOUP INSIDE THE DIRTY GAME OF DOPING IN SPORTS MARK JOHNSON Copyright © 2016 by Mark Johnson All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or photocopy or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations within critical articles and reviews. 3002 Sterling Circle, Suite 100 Boulder, Colorado 80301-2338 USA (303) 440-0601 · Fax (303) 444-6788 · E-mail [email protected] Distributed in the United States and Canada by Ingram Publisher Services A Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN 978-1-937715-27-4 For information on purchasing VeloPress books, please call (800) 811-4210, ext. 2138, or visit www.velopress.com. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). Art direction by Vicki Hopewell Cover: design by Andy Omel; concept by Mike Reisel; illustration by Jean-Francois Podevin Text set in Gotham and Melior 16 17 18 / 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Introduction ...................................... 1 1 The Origins of Doping ............................ 7 2 Pierre de Coubertin and the Fair-Play Myth ...... 27 3 The Fall of Coubertin’s Ideal ..................... 41 4 The Hot Roman Day When Doping Became Bad ..................................... 55 5 Doping Becomes a Crime........................ 75 6 The Birth of the World Anti-Doping Agency ..... 85 7 Doping and the Cold War........................ 97 8 Anabolic Steroids: Sports as Sputnik .......... -

Press Release

21.05.2021 Tappa 13 Ravenna – Verona km 198 LA CRONACA PARTENZA (Ravenna – ore 12.41 – 164 gli atleti al via) Escono subito in fuga Pellaud, Marengo e Rivi; il gruppo lascia spazio. Al km 30, il vantaggio dei fuggitivi è di 7’32”. Media dopo un’ora di corsa: 39,100 km/h. Traguardo Volante (Ferrara – km 67,5) I passaggi: Marengo, Rivi, Pellaud; a 5’00” Gaviria Rendon, Cimolai, Molano Benavides, Sagan, Consonni. Al km 68, Pellaud, si avvantaggia di una manciata di secondi sugli altri due compagni di fuga. Al km 80, Pellaud precede ancora di pochi secondi Marengo e Rivi; a 6’30” il gruppo. Media dopo due ore di corsa: 40,800 km/h. Al km 85, si forma nuovamente il terzetto in testa; il gruppo insegue a 6’43”. Al km 120, i fuggitivi hanno un vantaggio di 2’35” sul gruppo. Media dopo tre ore di corsa: 40,700 km/h. Traguardo Volante (Bagnolo San Vito – km 144,6) – Bonus abbuoni 3” – 2” – 1” I passaggi: Rivi, Marengo, Pellaud; il gruppo transita a 3’00”. Al km 151, il vantaggio dei fuggitivi è di 1’19” sul gruppo. Media dopo quattro ore di corsa: 40,800 km/h. Al km 170, il ritardo del gruppo è di 46”. Al km 191, il gruppo torna compatto. Al triangolo rosso, il gruppo si avvia alla volata generale. ARRIVO (Verona – km 198) Vittoria di Nizzolo su Affini, Sagan, Cimolai, Gaviria Rendon, Oldani, Pasqualon, Kanter, E.Viviani, Groenewegen e il resto del gruppo. Tempo del vincitore: 4h42’19”, alla media di 42,080 km/h. -

21St — 27Th February 2021

21ST — 27TH FEBRUARY 2021 YAS ISLAND 7 STAGE SAT, FEBRUARY 27TH 2021 TOP SPONSORS OFFICIAL CAR theuaetour.com 27th February 2021 THE STAGE REPORT Stage 7 – Yas Island Stage – km 147 START: Yas Mall – 127 riders are underway for the final stage as the flag is dropped at 13:05. Battistella, Sobrero and Brunel jump away early on, at km 1, immediately picking up the pace and growing their advantage. At km 3, the gap stands at 25”; at km 7: 1’50”. At km 10, the breakaway are 2’40” up the road already, and their lead keeps going up, reaching 3’05” at km 20. The situation settles, and the gap hovers around two and a half minutes from km 25 through 35. The pace goes on a notch in the peloton, as the first intermediate sprint approaches. Intermediate Sprint (Golf Gardens - km 42.6) Sobrero leads Brunel and Battistella through the IS. Dekker takes fourth place, 1’45” later. The break hits the -100 km marker. Average speed after one hour of racing: 45.600 km/h. The peloton returns to an easy pace, and the gap goes back up to 1’50” at km 55, and to 2’05” at km 60. Groves touches wheels and crashes with 85 km remaining to the finish. Seventy kilometres into the race, the chasers are 1’35” behind; at the -75 km marker, the gap stands at 1’18”. At km 80, the gap stands at 45”, and the peloton is about to split. Ineos Grenadiers are pulling at the front, trying to bridge across to the breakers, and eventually catching them up at approx. -

Respondents 25 Sca 001378

Questions about a Champion "If a misdeed arises in the search for truth, it is better to exhume it rather than conceal the truth." Saint Jerome. "When I wake up in the morning, I can look in the mirror and say: yes, I'm clean. It's up to you to prove that I am guilty." Lance Armstrong, Liberation, July 24,2001. "To deal with it, the teams must be clear on ethics. Someone crosses the line? He doesn't have the right to a second chance!" Lance Armstrong, L'Equipe, April 28, 2004. Between the World Road Champion encountered in a Norwegian night club, who sipped a beer, talked candidly, laughed easily and never let the conversation falter, and the cyclist with a stem, closed face, who fended off the July crowd, protected by a bodyguard or behind the smoked glass of the team bus, ten years had passed. July 1993. In the garden of an old-fashioned hotel near Grenoble, I interviewed Armstrong for three hours. It was the first professional season for this easygoing, slightly cowboyish, and very ambitious Texan. I left with a twenty-five-page interview, the chapter of a future book11 was writing about the Tour de France. I also took with me a real admiration for this young man, whom I thought had a promising future in cycling. Eight years later, in the spring of 2001, another interview. But the Tour of 1998 had changed things. Scandals and revelations were running rampant in cycling. Would my admiration stand the test? In August 1993, it was a happy, carefree, eloquent Armstrong, whom Pierre Ballester, met the evening after he won the World Championship in Oslo. -

Car Insurance Transfer Fees Raised 100 Percent

SUBSCRIPTION WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 18, 2015 RABI ALTHANI 29, 1436 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Car insurance transfer Min 12º Max 25º fees raised 100 percent High Tide 12:08 & 23:10 Some companies hike charges without ministry approval Low Tide 05:48 & 17:33 40 PAGES NO: 16437 150 FILS By Meshal Al-Enezi and Faten Omar KUWAIT: Some car insurance companies in Kuwait have Saudi king, Qatar emir discuss ties increased transfer fees despite not having approval from the Ministry of Commerce and Industry. When a RIYADH: Saudi Arabia’s King Salman held talks in driver transfers insurance from one car to another (for Riyadh yesterday with Qatar’s emir, in what an analyst instance in the case of buying a new or used vehicle), sees as part of a regional effort to strengthen ties insurance companies typically charge a fee of KD 3 for against the Islamic State (IS) group. Qatar’s Sheikh the transfer. Tamim bin Hamad Al-Thani is the latest Gulf leader to Now, however, several companies have upped this visit Riyadh this week, after Abu Dhabi Crown Prince fee 100 percent to KD 6. They have done so without pri- Mohamed bin Zayed Al-Nahyan and HH the Amir of or approval from the commerce ministry. “The union of Kuwait Sheikh Sabah Al-Ahmad Al-Sabah. He and the insurance companies agreed to increase the transfer fee Saudi monarch discussed the enhancement of their to KD 6 [from KD 3] as the fee for the issuance of new relations, as well as international developments, the documents,” explained a manager at a local car insur- official Saudi Press Agency said. -

Qatar Plans to Introduce Pay Reform for Migrant Workers

Sports FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 20, 2015 Kristoff strikes again, Cancellera retains lead AL MUSSANAH: Norway’s in-form Alexander despite beating Germans Kristina Vogel and second off the Germans’ previous mark. Chinese produced a stunning final lap of two Kristoff, who picked up three stages last week Miriam Welte in the final. But now, Gong has Russian pair Daria Shmeleva and Anastasia in the 500m sprint. Australians Kaarle in Qatar, came out on top in a bunch sprint to finally got her hands on a precious gold Voynova had set the pace in qualifying, McCulloch and Anna Meares took bronze by yesterday’s Tour of Oman third stage. The medal after she and Zhong broke the world although only beating Gong and Zhong by stunning Vogel and Welte. Katusha rider was followed home by Italian record, covering the 500m course in four hundredths of a second. But the The German pair had won the last three duo Andrea Guardini and Matteo Pelucchi at 32.034sec, shaving more than a tenth of a Russians had to settle for second as the world titles as well as the Olympics in the end of the 158.5km ride around Al London. In the men’s team sprint there was a Mussanah Sports City. “The team is good, our controversial finish as New Zealand, the origi- ‘work rhythm’ is working well and that gives nal winners, were demoted to second for an me a lot of confidence,” said Kristoff. early changeover. Switzerland’s Fabian Cancellara retained It meant hosts France won the gold the lead in the overall standings, 4sec clear of medal, with Gregory Bauge taking a fifth Spain’s Alejandro Valverde and 5sec up on world title in this discipline after winning four Austria’s Patrick Konrad. -

Worldteams Profiles

KEY RIDER BIOS | WORLDTEAMS PROFILES WORLDTEAMS AG2R LA MONDIALE (FRA) In the top flight for the past 24 years, the French squad shone once more at this year’s Tour de France, with Romain Bardet— who’ll be among the stars racing here in Canada—finishing second in the general classification. A season‐win total stuck at six has taken some of the shine off that success, but the fact remains that Vincent Lavenu’s team has been influential all season long. Founded in: 1992. Wins in 2016 (as of Aug. 22): 6 RIDERS TO WATCH Romain Bardet (FRA): Age 24, turned pro in 2012. Palmarès: 5 wins including two stages of the Tour de France. This season: 1 win; 2nd in the Tour de France, 2nd in the Critérium du Dauphiné, 2nd in the Tour of Oman. In 2016, this French climbing specialist continued his impressive rise to the higher echelons of world cycling, proving that he was one of the few men who could give Chris Froome a run for his money, both in the Critérium du Dauphiné and the Tour de France. Though tired after the Rio Olympics, he’ll be eager for end‐of‐season success in Canada, where he has done well in the past (5th in Montréal in 2014, and 7th last year). Alexis Vuillermoz (FRA): Age 28, turned pro in 2013. Palmarès: 5 wins including Stage 8 of the 2015 Tour de France. This season: 2nd in the GP de Plumelec, 3rd in the French National Championships. A series of crashes and health worries have kept his former mountain biking specialist from fulfilling the promise of his exciting 2015 season. -

Anti-Doping Advocate Questions Team Sky Ethics

Anti-Doping Advocate Questions Team Sky Ethics Anti-doping advocate and French former professional rider Christophe Bassons has questioned the ethics of Chris Froome and Team Sky. Bassons also issued a warning that rejection of Lance Armstrong by the cycling community may have dire consequences. The former French professional rider said he does not want to hear that Armstrong has been found hanging from a ceiling, because he thinks it is possible. Bassons, who was nicknamed 'Mr. Clean', said he sees comparisons between Team Sky and US Postal Service team. A key adversary of Armstrong, Bassons claims that the use of therapeutic user exemption certificates by Team Sky riders is no different to using the blood-boosting drug, erythropoietin (EPO). Bassons, speaking in Leeds for promoting his updated autobiography - ‘A Clean Break’ - said it was wrong for Chris Froome to race in Tour de Romandie using a therapeutic user exemption for an asthma medication. Froome was not violating the WADA or UCI rules but Bassons says he believes Team Sky and Froome have been exposed compromising their principles. Bassons remarked doping is about eliminating all obstacles to win a race and added that the fact is Froome has shown his mentality by taking this product, he had a problem, he was ill, and he took this product and he eliminated the obstacle to him winning. The former rider went on to remark that Armstrong said he had been tested 500 times and never tested positive and this is the same mentality guys have got today and they just don't want to test positive. -

Biographie Des Coureurs Et Info Worldteams

BIOGRAPHIE DES COUREURS ET INFO WORLDTEAMS WORLDTEAMS AG2R LA MONDIALE (FRA) Au plus haut niveau depuis 25 ans, la formation française vit une saison paradoxale. Elle a encore largement occupé l’actualité sur le Tour de France (Romain Bardet 6e, Pierre Latour meilleur jeune), mais a vécu ses plus belles émotions sur les classiques, avec la deuxième place de Silvan Dillier sur Paris‐Roubaix et la troisième de Romain Bardet sur Liège‐Bastogne‐Liège. Un symbole du volume pris par l’équipe de Vincent Lavenu, qui continue également de voir éclore les jeunes talents issus de son centre de formation à l’image de Benoît Cosnefroy, champion du monde espoirs 2017. Date de création : 1992. Victoires 2018 (au 20 août) : 11 LES HOMMES À SUIVRE Oliver Naesen (BEL) : 27 ans, professionnel en 2014. Palmarès : 5 victoires dont Bretagne Classic 2016, champion de Belgique 2017. Cette saison : 3e du GP de Francfort, 4e du GP E3, 6e Gand‐Wevelgem, 11e Tour des Flandres. En moins de deux saisons au sein de la formation française, l’ancien champion de Belgique s’est imposé comme un élément indispensable. Propulsé leader sur les classiques flandriennes, il ne lui manque pour l’heure qu’un peu de réussite pour espérer décrocher un monument comme le Tour des Flandres ou Paris‐Roubaix. Mais le Flamand se révèle aussi un capitaine de route exemplaire sur le Tour de France, où ses leaders apprécient sa science de la course comme sa bonne humeur quotidienne. Alexis Vuillermoz (FRA) : 30 ans, professionnel en 2013. Palmarès : 8 victoires dont 8e étape Tour de France 2015.