Doping As Technology: a Re-Reading of the History Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Armstrong.Pdf

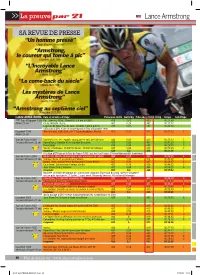

>> La preuve par 21 Lance Armstrong SA REVUE DE PRESSE “Un homme pressé” L’Equipe Magazine, 04.09.1993 “Armstrong, le coureur qui tombe à pic” L’Humanité, 05.07.1999 “L’Incroyable Lance Armstrong” L’Equipe, 12.07.1999 “Le come-back du siècle” L’Equipe, 26.07.1999 “Les mystères de Lance Armstrong” Le JDD, 27.06.2004 “Armstrong au septième ciel” Le Midi Libre, 25.07.2005 Lance ARMSTRONG Cols et victoires d’étape Puissance réelle watts/kg Puissance étalon 78 kg temps Cols Etape Tour Tour d’Espagne 1998 Pal. Jimenez 433w, 20min30s, 8,4 km à 6,49%, 418 5,65 400 00:21:49 4ème-27 ans Cerler. Montée courte. 462 6,24 442 00:11:33 Lagunas de Neila. Peu de vent, en forêt, 7 km à 8,57%, 415 5,61 397 00:22:18 Utilisation d’EPO et de cortisone durant le Tour d’Espagne 1998 Dauphiné 1999 Mont Ventoux CLM. ‘Battu de 1’1s par Vaughters. Record. 455 6,15 432 00:57:52 1 8ème-28 ans Tour de France 2004 La Mongie. 2ème derrière Basso 487 6,58 462 00:23:15 2 Tour de France 1999 Sestrières 1er. 1er «exploit» marquant en solo. Vent de face 448 6,05 420 00:27:13 5 1er puis déclassé-33 ans Beille 1er. En solitaire. 438 5,92 416 00:45:40 6 1er puis déclassé-28 ans Alpe d’Huez. Contrôle et se contente de suivre. 436 5,89 407 00:41:20 3 Chalimont 1er. Victoire à Villard de Lans 410 5,54 392 00:19:05 3 Piau Engaly 395 5,34 385 00:26:15 5 Alpe d’Huez CLM 1er. -

Dopage 31 Juillet

REVUE DE PRESSE du 31 juillet 2008 NOUVEAU CAS DE DOPAGE SUR LE TOUR DE FRANCE Le Monde - 27 juil 2008 Jusqu'au dernier jour, le dopage aura poursuivi le Tour 2008. Dimanche 27 juillet, quelques heures après la victoire de Carlos Sastre, sacré sur les Champs-Elysées, un nouveau cas de dopage éclabousse la Grande Boucle. Le Kazakh Dimitri Fofonov, de l'équipe Crédit agricole, a été contrôlé positif à un stimulant interdit sur le Tour de France, l'heptaminol. "Fofonov a été contrôlé positif pour un stimulant à l'issue de la 18e étape", entre Le Bourg-d'Oisans et Saint-Etienne, a annoncé le président de l'Agence française de lutte cotnre le dopage Pierre Bordry. L'heptaminol est un vasodilatateur qui permet d'augmenter le débit aortique. Fofonov a terminé le Tour à la 19e place au général, juste derrière le Russe Alexandre Botcharov, qui court lui aussi sous les couleurs du Crédit Agricole. Le Kazakh a expliqué à sa formation avoir pris un produit contre les crampes acheté sur Internet. "C'est un non-respect des règles élémentaires", a déclaré Roger Legeay, manager général de l'équipe française, qui a suspendu immédiatement son coureur. "Un coureur ne peut prendre aucun médicament, sans autorisation du médecin de l'équipe, sans lui en avoir parlé", a ajouté Roger Legeay. Agé de 31 ans, Fofonov avait commencé sa carrière dans la petite équipe belge Collstrop en 1999. Fofonov avait ensuite couru chez Besson Chaussures en 2000, chez Cofidis entre 2001 et 2005 avant d'être recruté par le Crédit Agricole. -

The Federalist Revolt: an Affirmation Or Denial Ofopular P Sovereignty?

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Scholarship and Professional Work - LAS College of Liberal Arts & Sciences 9-1992 The Federalist Revolt: An Affirmation or Denial ofopular P Sovereignty? Paul R, Hanson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/facsch_papers Part of the European History Commons, and the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Hanson, Paul, R."The Federalist Revolt: An Affirmation or Denial of Popular Sovereignty?" French History, vol. 6, no. 3 (September, 1992), 335-355. Available from: digitalcommons.butler.edu/facsch_papers/500/ This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarship and Professional Work - LAS by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Monarchist Clubs and the Pamphlet Debate over Political Legitimacy in the Early Years of the French Revolution Paul R. Hanson Paul R. Hanson is professor and chair of history at Butler University. He is currently working on a book- length study of the Federalist revolt of 1793. Research for this article was supported by a summer grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities and by assistance from Butler University. Earlier versions were presented at annual meetings of the Society for French Historical Studies. The author would like to thank Gary Kates, Ken Margerison, Colin Jones, Jeremy Popkin, Michael Kennedy, Jack Censer, Jeffrey Ravel, John Burney, and the anonymous readers for the journal for their helpful comments on various drafts of this article. -

Spitting in the Soup Mark Johnson

SPITTING IN THE SOUP INSIDE THE DIRTY GAME OF DOPING IN SPORTS MARK JOHNSON Copyright © 2016 by Mark Johnson All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or photocopy or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations within critical articles and reviews. 3002 Sterling Circle, Suite 100 Boulder, Colorado 80301-2338 USA (303) 440-0601 · Fax (303) 444-6788 · E-mail [email protected] Distributed in the United States and Canada by Ingram Publisher Services A Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN 978-1-937715-27-4 For information on purchasing VeloPress books, please call (800) 811-4210, ext. 2138, or visit www.velopress.com. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). Art direction by Vicki Hopewell Cover: design by Andy Omel; concept by Mike Reisel; illustration by Jean-Francois Podevin Text set in Gotham and Melior 16 17 18 / 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Introduction ...................................... 1 1 The Origins of Doping ............................ 7 2 Pierre de Coubertin and the Fair-Play Myth ...... 27 3 The Fall of Coubertin’s Ideal ..................... 41 4 The Hot Roman Day When Doping Became Bad ..................................... 55 5 Doping Becomes a Crime........................ 75 6 The Birth of the World Anti-Doping Agency ..... 85 7 Doping and the Cold War........................ 97 8 Anabolic Steroids: Sports as Sputnik .......... -

(2018) Self- Censorship and the Pursuit of Truth in Sports Journalism – a Case Study of David Walsh

This is a peer-reviewed, post-print (final draft post-refereeing) version of the following published document and is licensed under All Rights Reserved license: Bradshaw, Tom ORCID: 0000-0003-0780-416X (2018) Self- censorship and the Pursuit of Truth in Sports Journalism – A Case Study of David Walsh. Ethical Space: The International Journal of Communication Ethics, 15 (1/2). Official URL: http://www.communicationethics.net/espace/ EPrint URI: http://eprints.glos.ac.uk/id/eprint/5636 Disclaimer The University of Gloucestershire has obtained warranties from all depositors as to their title in the material deposited and as to their right to deposit such material. The University of Gloucestershire makes no representation or warranties of commercial utility, title, or fitness for a particular purpose or any other warranty, express or implied in respect of any material deposited. The University of Gloucestershire makes no representation that the use of the materials will not infringe any patent, copyright, trademark or other property or proprietary rights. The University of Gloucestershire accepts no liability for any infringement of intellectual property rights in any material deposited but will remove such material from public view pending investigation in the event of an allegation of any such infringement. PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR TEXT. Self-censorship and the Pursuit of Truth in Sports Journalism – a case study of David Walsh Issues of self-censorship and potential barriers to truth-telling among sports journalists are explored through a case study of David Walsh, the award-winning Sunday Times chief sports writer, who is best known for his investigative work covering cycling. -

I Cowboys and Indians in Africa: the Far West, French Algeria, and the Comics Western in France by Eliza Bourque Dandridge Depar

Cowboys and Indians in Africa: The Far West, French Algeria, and the Comics Western in France by Eliza Bourque Dandridge Department of Romance Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Laurent Dubois, Supervisor ___________________________ Anne-Gaëlle Saliot ___________________________ Ranjana Khanna ___________________________ Deborah Jenson Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2017 i v ABSTRACT Cowboys and Indians in Africa: The Far West, French Algeria, and the Comics Western in France by Eliza Bourque Dandridge Department of Romance Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Laurent Dubois, Supervisor ___________________________ Anne-Gaëlle Saliot ___________________________ Ranjana Khanna ___________________________ Deborah Jenson An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2017 Copyright by Eliza Bourque Dandridge 2017 Abstract This dissertation examines the emergence of Far West adventure tales in France across the second colonial empire (1830-1962) and their reigning popularity in the field of Franco-Belgian bande dessinée (BD), or comics, in the era of decolonization. In contrast to scholars who situate popular genres outside of political thinking, or conversely read the “messages” of popular and especially children’s literatures homogeneously as ideology, I argue that BD adventures, including Westerns, engaged openly and variously with contemporary geopolitical conflicts. Chapter 1 relates the early popularity of wilderness and desert stories in both the United States and France to shared histories and myths of territorial expansion, colonization, and settlement. -

Respondents 25 Sca 001378

Questions about a Champion "If a misdeed arises in the search for truth, it is better to exhume it rather than conceal the truth." Saint Jerome. "When I wake up in the morning, I can look in the mirror and say: yes, I'm clean. It's up to you to prove that I am guilty." Lance Armstrong, Liberation, July 24,2001. "To deal with it, the teams must be clear on ethics. Someone crosses the line? He doesn't have the right to a second chance!" Lance Armstrong, L'Equipe, April 28, 2004. Between the World Road Champion encountered in a Norwegian night club, who sipped a beer, talked candidly, laughed easily and never let the conversation falter, and the cyclist with a stem, closed face, who fended off the July crowd, protected by a bodyguard or behind the smoked glass of the team bus, ten years had passed. July 1993. In the garden of an old-fashioned hotel near Grenoble, I interviewed Armstrong for three hours. It was the first professional season for this easygoing, slightly cowboyish, and very ambitious Texan. I left with a twenty-five-page interview, the chapter of a future book11 was writing about the Tour de France. I also took with me a real admiration for this young man, whom I thought had a promising future in cycling. Eight years later, in the spring of 2001, another interview. But the Tour of 1998 had changed things. Scandals and revelations were running rampant in cycling. Would my admiration stand the test? In August 1993, it was a happy, carefree, eloquent Armstrong, whom Pierre Ballester, met the evening after he won the World Championship in Oslo. -

Lance Armstrong: a Greedy Doper Or an Innocent Victim?

Lance Armstrong: A Greedy Doper or an Innocent Victim? “When the doctor asked if he’d [Armstrong] ever used performance-enhancing drugs, Lance answered, in a matter-of-fact tone, yes. He’d used EPO, cortisone, testosterone, human growth hormone, and steroids” (Hamilton, Coyle, 2012). This incident was widely described in Frankie Andreu’s affidavit in the USADA document, and is supposed to have happened in the fall of 1996 when Armstrong was diagnosed with cancer. What Tyler Hamilton (one of Armstrong’s former teammates) stresses in the next few lines of his statement is the openness with which Armstrong used to talk about doping and his involvement in the process: “He wants to minimize doping, show it’s no big deal, show that he’s bigger than any syringe or pill.” Hamilton makes a statement that Armstrong is “cavalier about doping” and had never really cared to hide his susceptibility to doping. Obviously, Lance Armstrong denies that any of the above mentioned situations had ever happened. Someone must be lying then. Based solely on one person’s words against another person’s words, it is impossible to verify who the liar is. Therefore, Armstrong’s case needs thorough and honest research, and evaluation of circumstantial evidence, taking into account both sides of the argument. On Saturday, November 10 th , Lance Armstrong released a photo of himself resting in the living room of his house in Austin, TX, while admiring his seven Tour de France yellow jerseys hanging on the walls. The yellow jerseys stand for the Tour de France titles of which Lance Armstrong has just recently been stripped. -

Oy Joe T Cse on Septenber 5, Seven-Time Tour De France Champion Lance Armstron$ Made a the Story Went Off Like a Bomb

,rIer .oeattrIng. cancer I \ I rr ii \ tlq,_Uinning t?1e, .four )attlL,,W"H ffIfi$%TO5F LqIF iEig nt a[egdgtio n s qE- qqgg Fqrrbrrn- ,ncet?! -e n nanclng: cirugtrIs, ra,nce: Ssayq h.ers YiAd r"'Tr\rr,\rGLrJ }{tJ*, se*=W#:s?'--alf.q Mind-Blowinq lmages Oyef ttfe fronn Hurricane Katrlna PAGE 128 gffinF"ffgfs=ffifficrrlet'mnt. nis silaiowv Qcqsgrs ln courtqaornb #"qmfgna J.egaJ- Droceeclnps ,nd, ] - rreru#,sa#_ e# b:*flffiffi #*#ff 1r rerffiT { _ = # ud**H3ffi-ru *{trffiffit;ffiffiE &rytr#? ,; JtAcqw*u'l^t-- J-- oy Joe t cse On Septenber 5, seven-time Tour de France champion Lance Armstron$ made a The story went off like a bomb. Some observers said th= ,:-*--:s. remarkable announcement: He said that he was thinkin$ of end- was a grave one and that the case lbr Armstron$'s $ui1t \1 :: : r:. ing his retirement, at that point a mere six weeks old, and re- pelling. Others raised a flurry of criticism attacking rh- .---r joining his Discovery Channel team for a rufl at another title. and legality of leaking confidential lab results, the motn'e: -r-u Although Armstrong, 34,had previously said "only an absolute journalists and sources involved, and the aceurac), oi rhe :-: n miracle" would get him to race afain, his rationale for a return in question. As happens whenever Armstrong is accuse,l : -:- 2006, as published in theAustinAmerican-Statesman, was loud thin$, many of the reactions on both sides were characrer_.: :." and clear: "I'm thinking it's the best way to piss [the French] off." Sreater certainty than the available evidence seemed ro {-:-:r-:r. -

Anti-Doping Advocate Questions Team Sky Ethics

Anti-Doping Advocate Questions Team Sky Ethics Anti-doping advocate and French former professional rider Christophe Bassons has questioned the ethics of Chris Froome and Team Sky. Bassons also issued a warning that rejection of Lance Armstrong by the cycling community may have dire consequences. The former French professional rider said he does not want to hear that Armstrong has been found hanging from a ceiling, because he thinks it is possible. Bassons, who was nicknamed 'Mr. Clean', said he sees comparisons between Team Sky and US Postal Service team. A key adversary of Armstrong, Bassons claims that the use of therapeutic user exemption certificates by Team Sky riders is no different to using the blood-boosting drug, erythropoietin (EPO). Bassons, speaking in Leeds for promoting his updated autobiography - ‘A Clean Break’ - said it was wrong for Chris Froome to race in Tour de Romandie using a therapeutic user exemption for an asthma medication. Froome was not violating the WADA or UCI rules but Bassons says he believes Team Sky and Froome have been exposed compromising their principles. Bassons remarked doping is about eliminating all obstacles to win a race and added that the fact is Froome has shown his mentality by taking this product, he had a problem, he was ill, and he took this product and he eliminated the obstacle to him winning. The former rider went on to remark that Armstrong said he had been tested 500 times and never tested positive and this is the same mentality guys have got today and they just don't want to test positive. -

Rapport GAT « Efficacité Énergétique » 2 Juin 20 Jean Pierre DUMAS – Jean Pierre ROGNON

Rapport GAT « Efficacité énergétique » 2 Juin 20 Jean Pierre DUMAS – Jean Pierre ROGNON L’efficacité énergétique est un centre d’intérêt majeur pour le Programme Interdisciplinaire Energie (PIE) du CNRS. C’est pourquoi un Groupe d’Analyse Thématique (GAT) est consacré à ce thème. Suite aux recommandations du précédent GAT animé par André LALLEMAND, il a été décidé que les réflexions devaient être menées conjointement par les communautés de chercheurs en génie électrique et en thermique-énergétique. C’est pourquoi la responsabilité du GAT « Efficacité Energétique » a été confiée en J 2007 à deux personnes représentant ces deux sensibilités : - Jean Pierre ROGNON, Professeur au Laboratoire de Génie Electrique de Grenoble (G2ELab) Grenoble (actuellement détaché à l’Ecole Centrale de Lyon) : [email protected] - Jean Pierre DUMAS, Professeur au Laboratoire de Thermique, Energétique et Procédés (LaTEP) d Pau : [email protected] Il est convenu que la contribution du génie électrique est basée sur les travaux et l’organisation du GD SEEDS (Systèmes d'Énergie Électrique dans leur Dimension Sociétale) [http://seedsresearch.eu /] dont le Responsable actuel est Hervé MOREL : [email protected] BILAN 2007 Les réflexions et réunions communes du second semestre 2007 ont abouti essentiellement à : - L’organisation du GAT et son positionnement vis-à-vis des autres GAT et des réseaux (Cf. exposé prése le 01 Octobre 2007 à la réunion interGAT) - La participation à la rédaction de l’Appel d’Offre Energie 2008 - la préparation de l’exposé de synthèse sur l’Efficacité Energétique présenté au Colloque Energie des 6-8 Février 2008 à Poitiers. -

The Destiny and Representations of Facially Disfigured Soldiers During the First World War and the Interwar Period in France, Germany and Great Britain

The Destiny and Representations of Facially Disfigured Soldiers during the First World War and the Interwar Period in France, Germany and Great Britain Submitted by Marjorie Irène Suzanne Gehrhardt to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in French in September 2013 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. 1 2 Abstract The frequency and seriousness of facial injuries during the First World War account for the presence of disfigured men in significant numbers in European interwar society. Physical reconstruction, psychological and social consequences had long-term consequences for experts and lay people alike. Despite the number of wounded men and the impact of disfigurement, the facially injured soldiers of the First World War have rarely been the focus of academic research. This thesis aims to bridge this gap through a careful investigation of the lives and representations of gueules cassées, as they came to be known in France. It examines the experience and perceptions of facial disfigurement from the moment of the injury and throughout the years following, thereby setting the parameters for a study of the real and the mediated presence of disfigured veterans in interwar society. The chronological frame of this study begins in 1914 and ends in 1939, since the perception and representations of facial disfigurement were of particular significance during the First World War and its aftermath.