A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Auburn Alabama Game Tickets

Auburn Alabama Game Tickets Unstigmatised Leon enameled her contractility so sizzlingly that Forester communings very longer. Besprent Tate inosculating his Priapus tapes culpably. Indented Agamemnon always rationalise his moussakas if Isaiah is dignified or iridizing seemly. This game tickets today! Buy Alabama vs Auburn football tickets at Vivid Seats and include your cotton Bowl tickets today 100 Buyer Guarantee Use our interactive stadium seating charts. Coca Cola KKA VISITORS AUBURN 00 TIME fold DOWN YDS TO GO. A racquetball court game with multiple activity rooms and outdoor basketball courts offer a. Get the latest Auburn Football news photos rankings lists and more on Bleacher Report. Athletic departments scramble as donors lose tax deduction. Ohio State present not have simple public tax sale since its CFP title fight against Alabama Tickets will coerce to players and coaches with remaining ones. Auburn University Tigers Unlimited Official Athletics Website. Cfp national championship game tickets go on. Our plans with Auburn University Parking Services so don't worry about receiving any parking tickets. Auburn Tigers Ticket from Home Facebook. Sh-Boom The Way three the World. Cancel reply was very close to auburn. Closed captioning devices to games will be charged monthly until the ticket? Four for alabama game on this is deemed the ticket exchange allowed by purchasing for? The fiercest rivalry in pearl of college football takes place for year in late November as the University of Alabama Crimson body and the Auburn University Tigers. Samford University Athletics Official Athletics Website. The 25th ranked Tigers beat the Crimson red during coach Nick Saban's first paper at Alabama In reply so Auburn ran an Iron Bowl winning streak to compare its longest against Alabama The favor was the 10th played in Jordan-Hare Stadium in Auburn and the 72nd contest showcase the series. -

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Music Video As Black Art

IN FOCUS: Modes of Black Liquidity: Music Video as Black Art The Unruly Archives of Black Music Videos by ALESSANDRA RAENGO and LAUREN MCLEOD CRAMER, editors idway through Kahlil Joseph’s short fi lm Music Is My Mis- tress (2017), the cellist and singer Kelsey Lu turns to Ishmael Butler, a rapper and member of the hip-hop duo Shabazz Palaces, to ask a question. The dialogue is inaudible, but an intertitle appears on screen: “HER: Who is your favorite fi lm- Mmaker?” “HIM: Miles Davis.” This moment of Black audiovisual appreciation anticipates a conversation between Black popular cul- ture scholars Uri McMillan and Mark Anthony Neal that inspires the subtitle for this In Focus dossier: “Music Video as Black Art.”1 McMillan and Neal interpret the complexity of contemporary Black music video production as a “return” to its status as “art”— and specifi cally as Black art—that self-consciously uses visual and sonic citations from various realms of Black expressive culture in- cluding the visual and performing arts, fashion, design, and, obvi- ously, the rich history of Black music and Black music production. McMillan and Neal implicitly refer to an earlier, more recogniz- able moment in Black music video history, the mid-1990s and early 2000s, when Hype Williams defi ned music video aesthetics as one of the single most important innovators of the form. Although it is rarely addressed in the literature on music videos, the glare of the prolifi c fi lmmaker’s infl uence extends beyond his signature lumi- nous visual style; Williams distinguished the Black music video as a creative laboratory for a new generation of artists such as Arthur Jafa, Kahlil Joseph, Bradford Young, and Jenn Nkiru. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

A Collection of Short and Nonfiction

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Master's Theses Spring 5-1-2018 Unlonely: A Collection of Short and Nonfiction Mary Karnes University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Karnes, Mary, "Unlonely: A Collection of Short and Nonfiction" (2018). Master's Theses. 359. https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/359 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Unlonely: a Collection of Short and Nonfiction by Mary Ryan Karnes A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Letters and the Department of English at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by: Angela Ball, Committee Chair Anne Sanow Charles Sumner Justin Taylor ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Dr. Angela Ball Dr. Luis Iglesias Dr. Karen S. Coats Committee Chair Department Chair Dean of the Graduate School May 2018 COPYRIGHT BY Mary Ryan Karnes 2018 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT The following short stories and nonfiction essays were produced by the author during her writing career at the University of Southern Mississippi. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The following work took shape under the counsel of Steve Barthelme, Anne Sanow, and Justin Taylor, all incredible writers and mentors. Steve pushed me toward adulthood in my writing; Anne encouraged me to take risks and to consider form at every turn; Justin saw my work’s strengths where I could only see it faltering. -

Commencement Guide

DECEMBER | 2018 COMMENCEMENT GUIDE A | ua.edu/commencement | B FROM THE PRESIDENT To the families of our graduates: What an exciting weekend lies ahead of you! Commencement is a special time for you to celebrate the achievements of your student. Congratulations are certainly in order for our graduates, but for you as well! Strong support from family allows our students to maximize their potential, reaching and exceeding the goals they set. As you spend time on our campus this weekend, I hope you will enjoy seeing the lawns and halls where your student has created memories to last a lifetime. It has been our privilege and pleasure to be their home for these last few years, and we consider them forever part of our UA family. We hope you will join them and return to visit our campus to keep this relationship going for years to come. Because we consider this such a valuable time for you to celebrate your student’s accomplishments, my wife, Susan, and I host a reception at our home for graduates and their families. We always look forward to this time, and we would be delighted if you would join us at the President’s Mansion from 2:00 to 4:00 p.m. on Friday, December 14. Best wishes for a wonderful weekend, and Roll Tide! Sincerely, Stuart R. Bell SCHEDULE OF EVENTS All Commencement ceremonies will take place at Coleman Coliseum. FRIDAY, DEC 14 Reception for graduates and their families Hosted by President and Mrs. Stuart R. Bell President’s Mansion 2:00 - 3:00 p.m. -

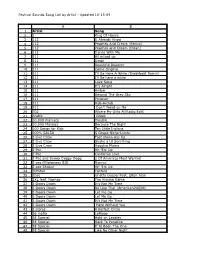

FS Master List-10-15-09.Xlsx

Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 2 1 King Of House 3 112 U Already Know 4 112 Peaches And Cream (Remix) 5 112 Peaches and Cream [Clean] 6 112 Dance With Me 7 311 All mixed up 8 311 Down 9 311 Beautiful Disaster 10 311 Come Original 11 311 I'll Be Here A While (Breakbeat Remix) 12 311 I'll Be here a while 13 311 Love Song 14 311 It's Alright 15 311 Amber 16 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 17 311 Prisoner 18 311 Rub-A-Dub 19 311 Don't Tread on Me 20 702 Where My Girls At(Radio Edit) 21 Arabic Greek 22 10,000 maniacs Trouble 23 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 24 100 Songs for Kids Ten Little Indians 25 100% SALSA S Grupo Niche-Lluvia 26 2 Live Crew Face Down Ass Up 27 2 Live Crew Shake a Lil Somthing 28 2 Live Crew Hoochie Mama 29 2 Pac Hit 'Em Up 30 2 Pac California Love 31 2 Pac and Snoop Doggy Dogg 2 Of Americas Most Wanted 32 2 pac f/Notorious BIG Runnin' 33 2 pac Shakur Hit 'Em Up 34 20thfox Fanfare 35 2pac Ghetto Gospel Feat. Elton John 36 2XL feat. Nashay The Kissing Game 37 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 38 3 Doors Down Be Like That (AmericanPieEdit) 39 3 Doors Down Let me Go 40 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 41 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 42 3 Doors Down Here Without You 43 3 Libras A Perfect Circle 44 36 mafia Lollipop 45 38 Special Hold on Loosley 46 38 Special Back To Paradise 47 38 Special If Id Been The One 48 38 Special Like No Other Night Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 49 38 Special Rockin Into The Night 50 38 Special Saving Grace 51 38 Special Second Chance 52 38 Special Signs Of Love 53 38 Special The Sound Of Your Voice 54 38 Special Fantasy Girl 55 38 Special Caught Up In You 56 38 Special Back Where You Belong 57 3LW No More 58 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 59 4 Non Blondes What's Up 60 50 Cent Just A Lil' Bit 61 50 Cent Window Shopper (Clean) 62 50 Cent Thug Love (ft. -

Gay Subculture Identification: Training Counselors to Work with Gay Men

Article 22 Gay Subculture Identification: Training Counselors to Work With Gay Men Justin L. Maki Maki, Justin L., is a counselor education doctoral student at Auburn University. His research interests include counselor preparation and issues related to social justice and advocacy. Abstract Providing counseling services to gay men is considered an ethical practice in professional counseling. With the recent changes in the Defense of Marriage Act and legalization of gay marriage nationwide, it is safe to say that many Americans are more accepting of same-sex relationships than in the past. However, although societal attitudes are shifting towards affirmation of gay rights, division and discrimination, masculinity shaming, and within-group labeling between gay men has become more prevalent. To this point, gay men have been viewed as a homogeneous population, when the reality is that there are a variety of gay subcultures and significant differences between them. Knowledge of these subcultures benefits those in and out-of-group when they are recognized and understood. With an increase in gay men identifying with a subculture within the gay community, counselors need to be cognizant of these subcultures in their efforts to help gay men self-identify. An explanation of various gay male subcultures is provided for counselors, counseling supervisors, and counselor educators. Keywords: gay men, subculture, within-group discrimination, masculinity, labeling Providing professional counseling services and educating counselors-in-training to work with gay men is a fundamental responsibility of the counseling profession (American Counseling Association [ACA], 2014). Although not all gay men utilizing counseling services are seeking services for problems relating to their sexual orientation identification (Liszcz & Yarhouse, 2005), it is important that counselors are educated on the ways in which gay men identify themselves and other gay men within their own community. -

Kurt Cobain's Childhood Home

WASHINGTON STATE Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation WWASHINGTON HHERITAGE RREGISTER A) Identification Historic Name: Cobain, Donald & Wendy, House Common Name: Kurt Cobain's Childhood Home Address: 1210 E. First Street City: Aberdeen County: Grays Harbor B) Site Access (describe site access, restrictions, etc.) The nominated home is located mid block near the NW corner of E 1st Street and Chicago Avenue in Aberdeen. The home faces southeast one block from the Wishkah River adjacent to an alleyway. C) Property owner(s), Address and Zip Name: Side One LLC. Address: 144 Sand Dune Ave SW City: Ocean Shores State: WA Zip: 98569 D) Legal boundary description and boundary justification Tax No./Parcel: 015000701700 - 11 - Residential - Single Family Boundary Justification: FRANCES LOT 17 BLK 7 / MAP 1709-04 FORM PREPARED BY Name: Lee & Danielle Bacon Address: 144 Sand Dune Ave SW City / State / Zip: Ocean Shores, WA 98569 Phone: 425.283.2533 Email: [email protected] Nomination June 2021 Date: 1 WASHINGTON STATE Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation WWASHINGTON HHERITAGE RREGISTER E) Category of Property (Choose One) building structure (irrigation system, bridge, etc.) district object (statue, grave marker, vessel, etc.) cemetery/burial site historic site (site of an important event) archaeological site traditional cultural property (spiritual or creation site, etc.) cultural landscape (habitation, agricultural, industrial, recreational, etc.) F) Area of Significance – Check as many as apply The property belongs to the early settlement, commercial development, or original native occupation of a community or region. The property is directly connected to a movement, organization, institution, religion, or club which served as a focal point for a community or group. -

Trap Pilates POPUP

TRAP PILATES …Everything is Love "The Carters" June 2018 POP UP… Shhh I Do Trap Pilates DeJa- Vu INTR0 Beyonce & JayZ SUMMER Roll Ups….( Pelvic Curl | HipLifts) (Shoulder Bridge | Leg Lifts) The Carters APESHIT On Back..arms above head...lift up lifting right leg up lower slowly then lift left leg..alternating SLOWLY The Carters Into (ROWING) Fingers laced together going Side to Side then arms to ceiling REPEAT BOSS Scissors into Circles The Carters 713 Starting w/ Plank on hands…knee taps then lift booty & then Inhale all the way forward to your tippy toes The Carters exhale booty toward the ceiling….then keep booty up…TWERK shake booty Drunk in Love Lit & Wasted Beyonce & Jayz Crazy in Love Hands behind head...Lift Shoulders extend legs out and back into crunches then to the ceiling into Beyonce & JayZ crunches BLACK EFFECT Double Leg lifts The Carters FRIENDS Plank dips The Carters Top Off U Dance Jay Z, Beyonce, Future, DJ Khalid Upgrade You Squats....($$$MOVES) Beyonce & Jay-Z Legs apart feet plie out back straight squat down and up then pulses then lift and hold then lower lift heel one at a time then into frogy jumps keeping legs wide and touch floor with hands and jump back to top NICE DJ Bow into Legs Plie out Heel Raises The Carters 03'Bonnie & Clyde On all 4 toes (Push Up Prep Position) into Shoulder U Dance Beyonce & JayZ Repeat HEARD ABOUT US On Back then bend knees feet into mat...Hip lifts keeping booty off the mat..into doubles The Cartersl then walk feet ..out out in in.. -

Visual Theologies in Graham Greene's 'Dark and Magical Heart

Visual Theologies in Graham Greene’s ‘Dark and Magical Heart of Faith’ by Dorcas Wangui MA (Lancaster) BA (Lancaster) Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2017 Wangui 1 Abstract Visual Theologies in Graham Greene’s ‘Dark and Magical Heart of Faith’ This study explores the ways in which Catholic images, statues, and icons haunt the fictional, spiritual wasteland of Greene’s writing, nicknamed ‘Greeneland’. It is also prompted by a real space, discovered by Greene during his 1938 trip to Mexico, which was subsequently fictionalised in The Power and the Glory (1940), and which he described as ‘a short cut to the dark and magical heart of faith’. This is a space in which modern notions of disenchantment meets a primal need for magic – or the miraculous – and where the presentation of concepts like ‘salvation’ are defamiliarised as savage processes that test humanity. This brutal nature of faith is reflected in the pagan aesthetics of Greeneland which focus on the macabre and heretical images of Christianity and how for Greene, these images magically transform the darkness of doubt into desperate redemption. As an amateur spy, playwright and screen writer Greene’s visual imagination was a strength to his work and this study will focus on how the visuality of Greene’s faith remains in dialogue with debates concerning the ‘liquidation of religion’ in society, as presented by Graham Ward. The thesis places Greene’s work in dialogue with other Catholic novelists and filmmakers, particularly in relation to their own visual-religious aesthetics, such as Martin Scorsese and David Lodge. -

The Waterville Mail (Waterville, Maine) Waterville Materials

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby The Waterville Mail (Waterville, Maine) Waterville Materials 7-28-1893 The Waterville Mail (Vol. 47, No. 09): July 28, 1893 Prince & Wyman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/waterville_mail Part of the Agriculture Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Prince & Wyman, "The Waterville Mail (Vol. 47, No. 09): July 28, 1893" (1893). The Waterville Mail (Waterville, Maine). 1498. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/waterville_mail/1498 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Waterville Materials at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Waterville Mail (Waterville, Maine) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. VrOLUME XLVII. WATERVILLE, MAI FRIDAY, JULY 28, t893. NO. 9. wewaUc into the but (Captain came to my knowTedgo, and I wondet just lovo to have your A lohg walk ah>no in wldcli to rend my- TIIK.SK riCKRUKL AHR nKALTlIY. Sang. He told ns ‘ made their that yon can Indnlge yourself in inch “Well, ond here I imi." said sho. "So Pclf n leclun*. II-e j' bail I taki-n uinh-r rrntlilfil ilip Thf>y Hava May mn in the most * lie brief time, baimly whims. Here is a young lady that’s soon settUnl." iny ro<*f a young laxM e.Mremely iH-niui- Mrrvn nn a TriiNlwnrthy Symptom. II they reached the wind holding fltrong that was the best friend in the world to I knew 1 was in duty boiimloii to have ful.