Paintings for the Pahari Rajas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

J&K Environment Impact Assessment Authority

0191-2474553/0194-2490602 Government of India Ministry of Environment, Forest & Climate Change J&K ENVIRONMENT IMPACT ASSESSMENT AUTHORITY (at) DEPARTMENT OF ECOLOGY, ENVIRONMENT AND REMOTE SENSING S.D.A. Colony, Bemina, Srinagar-190018 (May-Oct)/ Paryavaran Bhawan, Transport Nagar, Gladni, Jammu-180006 (Nov-Apr) Email: [email protected], website:www.parivesh.nic.in MINUTES OF MEETING OF THE JK ENVIRONMENT IMPACT ASSESSMENT AUTHORITY HELD ON 15th September, 2020 at 11.00 AM VIA VIDEO CONFERENCING. The following attended the meeting: 1. Mr. Lal Chand, IFS (Rtd.) Chairman, JKEIAA 2. Er. Nazir Ahmad (Rtd. Chief Engineer) Member, JKEIAA 3. Dr. Neelu Gera, IFS PCCF/Director, EE&RS Member Secretary, JKEIAA In pursuance to the Minutes of the Meeting of JKEAC held on 5th & 7th September, 2020, conveyed vide endorsement JKEAC/JK/2020/1870-83 dated:11-09-2020, a meeting of JK Environment Impact Assessment Authority was held on 15th September, 2020 at 11.00 A.M. via video conference. The following Agenda items were discussed: - Agenda Item No: 01, 02 and 03. i) Proposal Nos. SIA/JK/MIN/51865/2020 ii) SIA/JK/MIN/52027/2020 and iii) SIA/JK/MIN/52028/2020 Title of the Cases: iv) Grant of Terms of Reference for River Bed Material in Ujh River at Village- Jogyian, Tehsil Nagri Parole, District-Kathua, Area of Block 8.0 Ha. v) Grant of Terms of Reference for River Bed Material Minor Mineral Block Located in Ujh Rriver at Village Jagain, Tehsil Nagri Parole, District Kathua, Area of Block- 9.65 Ha. vi) Grant of Terms of Reference for River Bed Material Minor Mineral block located in Ujh river at village Jagain, Tehsil Nagri Parole, District Kathua, Area of block- 9.85 Ha. -

Mammalian Diversity and Management Plan for Jasrota Wildlife Sanctuary, Kathua (J&K)

Vol. 36: No. 1 Junuary-March 2009 MAMMALIAN DIVERSITY AND MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR JASROTA WILDLIFE SANCTUARY, KATHUA (J&K) by Sanjeev Kumar and D.N. Sahi Introduction marked and later surveyed for the presence of the animal. asrota Wildlife Sanctuary, with an area of 10.04 Jkm2, is situated on the right bank of the Ujh Roadside surveys river in district Kathua, J&K State, between 32o27’ These surveys were made both on foot and by and 32o31’ N latitudes and 75o22’ and 75o26’ E vehicle. These were successful particularly in case longitudes. The elevation ranges from 356 to 520 of Rhesus monkeys, which can tolerate the m. Climatic conditions in study area are generally presence of humans and allow the observations dry sub-humid. The summer season runs from to be made from close quarters. Counting was April to mid-July, with maximum summer done and members of different troops were temperatures varying between 36oC to 42oC. The identified by wounds on exposed parts, broken legs winter season runs from November to February. or arms, scars or by some other deformity. Many Spring is from mid-February to mid-April. The times, jackals and hares were also encountered |Mammalian diversity and management plan for Jasrota Wildlife Sanctuary| average cumulative rainfall is 100 cm. during the roadside surveys. The flora is comprised of broad-leaved associates, Point transect method namely Lannea coromandelica, Dendro- This method was also tried, but did not prove as calamus strictus, Acacia catechu, A. arabica, effective as the line transect method and roadside Dalbergia sissoo, Bombax ceiba, Ficus survey. -

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

Pahari Miniature Schools

The Art Of Eurasia Искусство Евразии No. 1 (1) ● 2015 № 1 (1) ● 2015 eISSN 2518-7767 DOI 10.25712/ASTU.2518-7767.2015.01.002 PAHARI MINIATURE SCHOOLS Om Chand Handa Doctor of history and literature, Director of Infinity Foundation, Honorary Member of Kalp Foundation. India, Shimla. [email protected] Scientific translation: I.V. Fotieva. Abstract The article is devoted to the study of miniature painting in the Himalayas – the Pahari Miniature Painting school. The author focuses on the formation and development of this artistic tradition in the art of India, as well as the features of technics, stylistic and thematic varieties of miniatures on paper and embroidery painting. Keywords: fine-arts of India, genesis, Pahari Miniature Painting, Basohali style, Mughal era, paper miniature, embroidery painting. Bibliographic description for citation: Handa O.C. Pahari miniature schools. Iskusstvo Evrazii – The Art of Eurasia, 2015, No. 1 (1), pp. 25-48. DOI: 10.25712/ASTU.2518-7767.2015.01.002. Available at: https://readymag.com/622940/8/ (In Russian & English). Before we start discussion on the miniature painting in the Himalayan region, known popularly the world over as the Pahari Painting or the Pahari Miniature Painting, it may be necessary to trace the genesis of this fine art tradition in the native roots and the associated alien factors that encouraged its effloresces in various stylistic and thematic varieties. In fact, painting has since ages past remained an art of the common people that the people have been executing on various festive occasions. However, the folk arts tend to become refined and complex in the hands of the few gifted ones among the common folks. -

Relevance of Sri Krishna to Karyakartas

Balagokulam 5HOHYDQFHRI6UL.ULVKQDWR.DU\DNDUWDV Sri Krishna spells out the purpose his incarnation in Geeta as “to establish Dharma”(Dharma sansthaapanaarthaaya ). In our Sangh Prarthana recited in every Shakha, we say that we are organizing to protect Dharma (kritvaa asmad dharma rakshanam). In a way, we are only instruments in fulfilling the mission of Sri Krishna. Krishna’s life can be a beacon of light for us walking in this path. Rama and Krishna – most worshipped avatars Many are the incarnations of God. But Sri Rama and Sri Krishna are the most worshipped because their lives present the situations that we encounter in our own lives. They embodied the ideals in life by following which we all can enrich our own lives. Sri Rama’s image brings in our mind a sense of awe and respect. His personality is tall and magnanimous. Whereas, Sri Krishna’s personality has two sides. He is at once very extra-ordinary, superhuman and at once he is that adorable child from next-door, enchanting and playful. Every mother can see Krishna in her own child. Friend of all Krishna showed his divine and super-human powers again and again and yet ensured that there is no distance between him and others. Yashoda was awed to see the entire universe in his mouth. The very next moment, he was the same mischievous child, playing hide-and-seek with her. His friends were frightened and overwhelmed to see their friend subduing the fearsome snake (Kalinga). It took only a few minutes before they all went to steal the butter and play in the forest. -

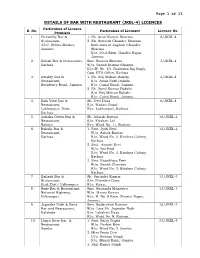

JKEL-4) LICENCES Particulars of Licence S

Page 1 of 13 DETAILS OF BAR WITH RESTAURANT (JKEL-4) LICENCES Particulars of Licence S. No. Particulars of Licensee Licence No. Premises 1. Piccadilly Bar & 1. Sh. Arun Kumar Sharma 2/JKEL-4 Restaurant, 2. Sh. Romesh Chander Sharma 23-C, Nehru Market, both sons of Jagdish Chander Jammu Sharma R/o. 20-A Extn. Gandhi Nagar, Jammu. 2. Satish Bar & Restaurant, Smt. Suman Sharma 3/JKEL-4 Kathua W/o. Satish Kumar Sharma R/o W. No. 10, Chabutra Raj Bagh, Opp. ETO Office, Kathua 3. Kwality Bar & 1. Sh. Brij Mohan Bakshi 4/JKEL-4 Restaurant, S/o. Amar Nath Bakshi Residency Road, Jammu R/o. Canal Road, Jammu. 2. Sh. Sunil Kumar Bakshi S/o. Brij Mohan Bakshi R/o. Canal Road, Jammu. 4. Ravi View Bar & Sh. Devi Dass 8/JKEL-4 Restaurant, S/o. Madan Gopal Lakhanpur, Distt. R/o. Lakhanpur, Kathua. Kathua. 5. Ashoka Green Bar & Sh. Adarsh Rattan 10/JKEL-4 Restaurant, S/o. Krishan Lal Rajouri R/o. Ward No. 11, Rajouri. 6. Bakshi Bar & 1. Smt. Jyoti Devi 12/JKEL-4 Restaurant, W/o. Ashok Kumar Kathua. R/o. Ward No. 3, Krishna Colony, Kathua. 2. Smt . Amarti Devi W/o. Sat Paul R/o. Ward No. 3, Krishna Colony, Kathua. 3. Smt. Kaushlaya Devi W/o. Satish Chander R/o. Ward No. 3, Krishna Colony, Kathua. 7. Kailash Bar & Sh. Surinder Kumar 13/JKEL-4 Restaurant, S/o. Pitamber Dass Kud, Distt. Udhampur. R/o. Katra. 8. Roxy Bar & Restaurant, Smt. Sunanda Mangotra 14/JKEL-4 National Highway, W/o. -

A Revolution in Kṛṣṇaism: the Cult of Gopāla Author(S): Norvin Hein Source: History of Religions , May, 1986, Vol

A Revolution in Kṛṣṇaism: The Cult of Gopāla Author(s): Norvin Hein Source: History of Religions , May, 1986, Vol. 25, No. 4, Religion and Change: ASSR Anniversary Volume (May, 1986), pp. 296-317 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1062622 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to History of Religions This content downloaded from 130.132.173.217 on Fri, 18 Dec 2020 20:12:45 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Norvin Hein A REVOLUTION IN KRSNAISM: THE CULT OF GOPALA Beginning about A.D. 300 a mutation occurred in Vaisnava mythology in which the ideals of the Krsna worshipers were turned upside down. The Harivamsa Purana, which was composed at about that time, related in thirty-one chapters (chaps. 47-78) the childhood of Krsna that he had spent among the cowherds.1 The tales had never been told in Hindu literature before. As new as the narratives themselves was their implicit theology. The old adoration of Krsna as moral preceptor went into a long quiescence. -

South Asian Art a Resource for Classroom Teachers

South Asian Art A Resource for Classroom Teachers South Asian Art A Resource for Classroom Teachers Contents 2 Introduction 3 Acknowledgments 4 Map of South Asia 6 Religions of South Asia 8 Connections to Educational Standards Works of Art Hinduism 10 The Sun God (Surya, Sun God) 12 Dancing Ganesha 14 The Gods Sing and Dance for Shiva and Parvati 16 The Monkeys and Bears Build a Bridge to Lanka 18 Krishna Lifts Mount Govardhana Jainism 20 Harinegameshin Transfers Mahavira’s Embryo 22 Jina (Jain Savior-Saint) Seated in Meditation Islam 24 Qasam al-Abbas Arrives from Mecca and Crushes Tahmasp with a Mace 26 Prince Manohar Receives a Magic Ring from a Hermit Buddhism 28 Avalokiteshvara, Bodhisattva of Compassion 30 Vajradhara (the source of all teachings on how to achieve enlightenment) CONTENTS Introduction The Philadelphia Museum of Art is home to one of the most important collections of South Asian and Himalayan art in the Western Hemisphere. The collection includes sculptures, paintings, textiles, architecture, and decorative arts. It spans over two thousand years and encompasses an area of the world that today includes multiple nations and nearly a third of the planet’s population. This vast region has produced thousands of civilizations, birthed major religious traditions, and provided fundamental innovations in the arts and sciences. This teaching resource highlights eleven works of art that reflect the diverse cultures and religions of South Asia and the extraordinary beauty and variety of artworks produced in the region over the centuries. We hope that you enjoy exploring these works of art with your students, looking closely together, and talking about responses to what you see. -

Islamic and Indian Art Including Sikh Treasures and Arts of the Punjab

Islamic and Indian Art Including Sikh Treasures and Arts of the Punjab New Bond Street, London | 23 October, 2018 Registration and Bidding Form (Attendee / Absentee / Online / Telephone Bidding) Please circle your bidding method above. Paddle number (for office use only) This sale will be conducted in accordance with 23 October 2018 Bonhams’ Conditions of Sale and bidding and buying Sale title: Sale date: at the Sale will be regulated by these Conditions. You should read the Conditions in conjunction with Sale no. Sale venue: New Bond Street the Sale Information relating to this Sale which sets out the charges payable by you on the purchases If you are not attending the sale in person, please provide details of the Lots on which you wish to bid at least 24 hours you make and other terms relating to bidding and prior to the sale. Bids will be rounded down to the nearest increment. Please refer to the Notice to Bidders in the catalogue buying at the Sale. You should ask any questions you for further information relating to Bonhams executing telephone, online or absentee bids on your behalf. Bonhams will have about the Conditions before signing this form. endeavour to execute these bids on your behalf but will not be liable for any errors or failing to execute bids. These Conditions also contain certain undertakings by bidders and buyers and limit Bonhams’ liability to General Bid Increments: bidders and buyers. £10 - 200 .....................by 10s £10,000 - 20,000 .........by 1,000s £200 - 500 ...................by 20 / 50 / 80s £20,000 -

Srimad-Bhagavatam – Canto Ten” by His Divine Grace A.C

“Srimad-Bhagavatam – Canto Ten” by His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. Summary: Srimad-Bhagavatam is compared to the ripened fruit of Vedic knowledge. Also known as the Bhagavata Purana, this multi-volume work elaborates on the pastimes of Lord Krishna and His devotees, and includes detailed descriptions of, among other phenomena, the process of creation and annihilation of the universe. His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada considered the translation of the Bhagavatam his life’s work. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This is an evaluation copy of the printed version of this book, and is NOT FOR RESALE. This evaluation copy is intended for personal non- commercial use only, under the “fair use” guidelines established by international copyright laws. You may use this electronic file to evaluate the printed version of this book, for your own private use, or for short excerpts used in academic works, research, student papers, presentations, and the like. You can distribute this evaluation copy to others over the Internet, so long as you keep this copyright information intact. You may not reproduce more than ten percent (10%) of this book in any media without the express written permission from the copyright holders. Reference any excerpts in the following way: “Excerpted from “Srimad-Bhagavatam” by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, courtesy of the Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International, www.Krishna.com.” This book and electronic file is Copyright 1977-2003 Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International, 3764 Watseka Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90034, USA. All rights reserved. For any questions, comments, correspondence, or to evaluate dozens of other books in this collection, visit the website of the publishers, www.Krishna.com. -

1 No. F. 1-73/2011-Sch.1 Government of India Ministry of Human

No. F. 1-73/2011-Sch.1 Government of India Ministry of Human Resource Development Department of School Education & Literacy School-1 Section ***** Dated, 12 th December, 2011 To The Secretary, in-charge of Secondary Education of Jammu & Kashmir. Subject: 19 th meeting of Project Approval Board (PAB) for Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan (RMSA) held on 15 th November, 2011 to consider Annual Plan Proposal 2011-12 of State of Jammu & Kashmir. Sir, I am directed to forward herewith minutes of the 19th meeting of PAB for RMSA held on 15 th November, 2011 to consider Annual Work Plan & Budget (AWP&B) 2011-12 of State of Jammu & Kashmir for information and necessary action at your end. Yours faithfully, (Sanjay Gupta) Under Secretary to the Government of India Encl: - as above Copy to:- 1. EC to Secretary (SE&L) 2. PS to JS & FA 3. PPS to JS (SE-I) 4. VC, NUEPA, New Delhi 5. Chairman, NIOS, NOIDA. 6. Director, NCERT, New Delhi. 7. Sr. Advisor, Education, Planning Commission, New Delhi 1 MINUTES OF THE 19 TH MEETING OF THE PROJECT APPROVAL BOARD (PAB) HELD ON 15 TH NOVEMBER, 2011 TO CONSIDER ANNUAL WORK PLAN AND BUDGET 2011-12 UNDER RASHTRIYA MADHYAMIK SHIKSHA ABHIYAN (RMSA) FOR THE STATE OF JAMMU & KASHMIR, THE PROPOSALS OF NCERT AND REVIEW OF SEMIS IMPLEMENTED BY NUEPA. The 19 th Meeting of the Project Approval Board (PAB) to consider the Annual Work Plan and Budget 2011-12 under Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan (RMSA) for the State of Jammu & Kashmir, the proposals of NCERT and review of submits by NUEPA was held on 15 th November, 2011 at 3.00 p.m.