Loyola Neuroscience Lab Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Diagnosis of Subarachnoid Haemorrhage

Journal ofNeurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1990;53:365-372 365 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.53.5.365 on 1 May 1990. Downloaded from OCCASIONAL REVIEW The diagnosis of subarachnoid haemorrhage M Vermeulen, J van Gijn Lumbar puncture (LP) has for a long time been of 55 patients with SAH who had LP, before the mainstay of diagnosis in patients who CT scanning and within 12 hours of the bleed. presented with symptoms or signs of subarach- Intracranial haematomas with brain shift was noid haemorrhage (SAH). At present, com- proven by operation or subsequent CT scan- puted tomography (CT) has replaced LP for ning in six of the seven patients, and it was this indication. In this review we shall outline suspected in the remaining patient who stop- the reasons for this change in diagnostic ped breathing at the end of the procedure.5 approach. In the first place, there are draw- Rebleeding may have occurred in some ofthese backs in starting with an LP. One of these is patients. that patients with SAH may harbour an We therefore agree with Hillman that it is intracerebral haematoma, even if they are fully advisable to perform a CT scan first in all conscious, and that withdrawal of cerebro- patients who present within 72 hours of a spinal fluid (CSF) may occasionally precipitate suspected SAH, even if this requires referral to brain shift and herniation. Another disadvan- another centre.4 tage of LP is the difficulty in distinguishing It could be argued that by first performing between a traumatic tap and true subarachnoid CT the diagnosis may be delayed and that this haemorrhage. -

Anatomical Variations of Circle of Willis - a Cadaveric Study

International Surgery Journal Singh R et al. Int Surg J. 2017 Apr;4(4):1249-1258 http://www.ijsurgery.com pISSN 2349-3305 | eISSN 2349-2902 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18203/2349-2902.isj20171016 Original Research Article Anatomical variations of circle of Willis - a cadaveric study Ramanuj Singh, Ajay Babu Kannabathula*, Himadri Sunam, Debajani Deka Department of Anatomy, Gouri devi Institute of Medical Sciences and Hospital, Durgapur, West Bengal, India Received: 02 March 2017 Accepted: 09 March 2017 *Correspondence: Dr. Ajay Babu Kannabathula, E-mail: [email protected] Copyright: © the author(s), publisher and licensee Medip Academy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT Background: The circle of Willis (CW) is a vascular network formed at the base of skull in the interpeduncular fossa. Its anterior part is formed by the anterior cerebral artery, from either side. Anterior communicating artery connects the right and left anterior cerebral arteries. Posteriorly, the basilar artery divides into right and left posterior cerebral arteries and each join to ipsilateral internal carotid artery through a posterior communicating artery. Anterior communicating artery and posterior communicating arteries are important component of circle of Willis, acts as collateral channel to stabilize blood flow. In the present study, anatomical variations in the circle of Willis were noted. Methods: 75 apparently normal formalin fixed brain specimens were collected from human cadavers. 55 Normal anatomical pattern and 20 variations of circle of Willis were studied. -

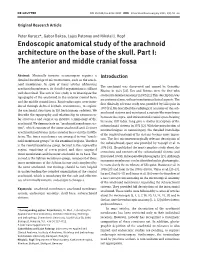

Endoscopic Anatomical Study of the Arachnoid Architecture on the Base of the Skull

DOI 10.1515/ins-2012-0005 Innovative Neurosurgery 2013; 1(1): 55–66 Original Research Article Peter Kurucz* , Gabor Baksa , Lajos Patonay and Nikolai J. Hopf Endoscopic anatomical study of the arachnoid architecture on the base of the skull. Part I: The anterior and middle cranial fossa Abstract: Minimally invasive neurosurgery requires a Introduction detailed knowledge of microstructures, such as the arach- noid membranes. In spite of many articles addressing The arachnoid was discovered and named by Gerardus arachnoid membranes, its detailed organization is still not Blasius in 1664 [ 22 ]. Key and Retzius were the first who well described. The aim of this study is to investigate the studied its detailed anatomy in 1875 [ 11 ]. This description was topography of the arachnoid in the anterior cranial fossa an anatomical one, without mentioning clinical aspects. The and the middle cranial fossa. Rigid endoscopes were intro- first clinically relevant study was provided by Liliequist in duced through defined keyhole craniotomies, to explore 1959 [ 13 ]. He described the radiological anatomy of the sub- the arachnoid structures in 110 fresh human cadavers. We arachnoid cisterns and mentioned a curtain-like membrane describe the topography and relationship to neurovascu- between the supra- and infratentorial cranial space bearing lar structures and suggest an intuitive terminology of the his name still today. Lang gave a similar description of the arachnoid. We demonstrate an “ arachnoid membrane sys- subarachnoid cisterns in 1973 [ 12 ]. With the introduction of tem ” , which consists of the outer arachnoid and 23 inner microtechniques in neurosurgery, the detailed knowledge arachnoid membranes in the anterior fossa and the middle of the surgical anatomy of the cisterns became more impor- fossa. -

A Suprasellar Subarachnoid Pouch; Aetiological Considerations

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.47.10.1066 on 1 October 1984. Downloaded from Journal ofNeurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1984;47:1066-1074 A suprasellar subarachnoid pouch; aetiological considerations O BINITIE, BERNARD WILLIAMS, CP CASE From the Midland Centre for Neurosurgery and Neurology, Smethwick, Warley, West Midlands, UK SUMMARY A child with hydrocephalus treated by a valved shunt was reinvestigated after develop- ing a shunt infection. A pouch was discovered invaginating the floor of the third ventricle and filling slowly with CSF from the region of the interpeduncular cistern. Histology and mechanisms of this pouch formation are discussed. Arachnoid lined cysts in the subarachnoid space There was a family history of one sibling with spina form about one percent of space occupying intra- bifida and two normal siblings aged four and six cranial lesions in several series.'- These cysts may years. He was admitted to the Midland Centre for be separate from the normal subarachnoid space or Neurosurgery and Neurology (MCNN) at the age of may communicate with it. The term cyst" may be one and a half years because his head had been guest. Protected by copyright. applied to a fluid collection which has no macro- increasing in size over the previous six months. It scopic connection with other fluid containing space was also noted that his arms and legs were stiff, that and pouch" to a fluid collection with one entrance he did not attempt to crawl and his vocabulary was or exit.4 Cavities containing cerebrospinal fluid limited to basic words only. -

Anatomy-Nerve Tracking

INJECTABLES ANATOMY www.aestheticmed.co.uk Nerve tracking Dr Sotirios Foutsizoglou on the anatomy of the facial nerve he anatomy of the human face has received enormous attention during the last few years, as a plethora of anti- ageing procedures, both surgical and non-surgical, are being performed with increasing frequency. The success of each of those procedures is greatly dependent on Tthe sound knowledge of the underlying facial anatomy and the understanding of the age-related changes occurring in the facial skeleton, ligaments, muscles, facial fat compartments, and skin. The facial nerve is the most important motor nerve of the face as it is the sole motor supply to all the muscles of facial expression and other muscles derived from the mesenchyme in the embryonic second pharyngeal arch.1 The danger zone for facial nerve injury has been well described. Confidence when approaching the nerve and its branches comes from an understanding of its three dimensional course relative to the layered facial soft tissue and being aware of surface anatomy landmarks and measurements as will be discussed in this article. Aesthetic medicine is not static, it is ever evolving and new exciting knowledge emerges every day unmasking the relationship of the ageing process and the macroscopic and microscopic (intrinsic) age-related changes. Sound anatomical knowledge, taking into consideration the natural balance between the different facial structures and facial layers, is fundamental to understanding these changes which will subsequently help us develop more effective, natural, long-standing and most importantly, safer rejuvenating treatments and procedures. The soft tissue of the face is arranged in five layers: 1) Skin; 2) Subcutaneous fat layer; 3) Superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS); 4) Areolar tissue or loose connective tissue (most clearly seen in the scalp and forehead); 5) Deep fascia formed by the periosteum of facial bones and the fascial covering of the muscles of mastication (lateral face). -

Cranial Nervesnerves

CranialCranial NervesNerves 1. Cranial nerves - overview: origin and peripheral distribution functional components and modality innervation zones I. Olfactory nerves, nn. olfactorii II. Optic nerve, n. opticus III. Oculomotor nerve, n. oculomotorius IV. Trochlear nerve, n. trochlearis V. Trigeminal nerve, n. trigeminus VI. Abducent nerve, n. abducens VII. Facial nerve, n. facialis VIII. Vestibulocochlear nerve, n. Vestibulocochlearis IX. Glossopharyngeal nerve, n. glossopharyngeus X. Vagus nerve, n. vagus XI. Accessory nerve, n. accessorius XII. Hypoglossal nerve, n. hypoglossus Cranial nerves CranialCranial nervesnerves 0. N. terminalis I. N. olfactorius II. N. opticus III. N. oculomotorius IV. N. trochlearis V. N. trigeminus VI. N. abducens VII. N. facialis VIII. N. vestibulocochlearis IX. N. glossopharyngeus X. N. vagus XI. N. accessorius XII. N. hypoglossus Prof. Dr. Nikolai Lazarov 2 Cranial nerves FunctionalFunctional classificationclassification purely sensory (afferent ): n. olfactorius n. opticus n. vestibulocochlearis purely motor (efferent): n. oculomotorius n. trochlearis n. abducens n. accessorius n. hypoglossus mixed (sensory&motor ): n. trigeminus n. facialis n. glossopharyngeus n. vagus autonomic (parasympathetic( ): n. oculomotorius n. facialis n. glossopharyngeus n. vagus Prof. Dr. Nikolai Lazarov 3 Cranial nerves AnatomicAnatomic relationshipsrelationships Location within the brainstem: ventrally: n. olfactorius n. opticus n. oculomotorius n. abducens n. hypoglossus laterally: n. trigeminus -

Embryology, Anatomy, and Physiology of the Afferent Visual Pathway

CHAPTER 1 Embryology, Anatomy, and Physiology of the Afferent Visual Pathway Joseph F. Rizzo III RETINA Physiology Embryology of the Eye and Retina Blood Supply Basic Anatomy and Physiology POSTGENICULATE VISUAL SENSORY PATHWAYS Overview of Retinal Outflow: Parallel Pathways Embryology OPTIC NERVE Anatomy of the Optic Radiations Embryology Blood Supply General Anatomy CORTICAL VISUAL AREAS Optic Nerve Blood Supply Cortical Area V1 Optic Nerve Sheaths Cortical Area V2 Optic Nerve Axons Cortical Areas V3 and V3A OPTIC CHIASM Dorsal and Ventral Visual Streams Embryology Cortical Area V5 Gross Anatomy of the Chiasm and Perichiasmal Region Cortical Area V4 Organization of Nerve Fibers within the Optic Chiasm Area TE Blood Supply Cortical Area V6 OPTIC TRACT OTHER CEREBRAL AREASCONTRIBUTING TO VISUAL LATERAL GENICULATE NUCLEUSPERCEPTION Anatomic and Functional Organization The brain devotes more cells and connections to vision lular, magnocellular, and koniocellular pathways—each of than any other sense or motor function. This chapter presents which contributes to visual processing at the primary visual an overview of the development, anatomy, and physiology cortex. Beyond the primary visual cortex, two streams of of this extremely complex but fascinating system. Of neces- information flow develop: the dorsal stream, primarily for sity, the subject matter is greatly abridged, although special detection of where objects are and for motion perception, attention is given to principles that relate to clinical neuro- and the ventral stream, primarily for detection of what ophthalmology. objects are (including their color, depth, and form). At Light initiates a cascade of cellular responses in the retina every level of the visual system, however, information that begins as a slow, graded response of the photoreceptors among these ‘‘parallel’’ pathways is shared by intercellular, and transforms into a volley of coordinated action potentials thalamic-cortical, and intercortical connections. -

Surgical Treatment of Bronchial Asthma by Resection of the Laryngeal Nerve

Surgical treatment of bronchial asthma by resection of the laryngeal nerve Ubaidullo Kurbon, Hamza Dodariyon, Abdumalik Davlatov, Sitora Janobilova, Amu Therwath, Massoud Mirshahi To cite this version: Ubaidullo Kurbon, Hamza Dodariyon, Abdumalik Davlatov, Sitora Janobilova, Amu Therwath, et al.. Surgical treatment of bronchial asthma by resection of the laryngeal nerve. BMC Surgery, BioMed Central, 2015, 15 (1), pp.109. 10.1186/s12893-015-0093-2. inserm-01264486 HAL Id: inserm-01264486 https://www.hal.inserm.fr/inserm-01264486 Submitted on 29 Jan 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Kurbon et al. BMC Surgery (2015) 15:109 DOI 10.1186/s12893-015-0093-2 TECHNICAL ADVANCE Open Access Surgical treatment of bronchial asthma by resection of the laryngeal nerve Ubaidullo Kurbon1, Hamza Dodariyon1, Abdumalik Davlatov1, Sitora Janobilova1, Amu Therwath2 and Massoud Mirshahi1,2* Abstract Background: Management of asthma in chronically affected patients is a serious health problem. Our aim was to show that surgical treatment of chronic bronchial asthma by unilateral resection of the internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve (ib-SLN) is an adequateand lasting remedial response. Patients and methods: In a retrospective study, 41 (26 male and 15 female) patients with bronchial chronic asthma were treated surgically during the period between 2005 and 2013. -

Subarachnoid Trabeculae: a Comprehensive Review of Their Embryology, Histology, Morphology, and Surgical Significance Martin M

Literature Review Subarachnoid Trabeculae: A Comprehensive Review of Their Embryology, Histology, Morphology, and Surgical Significance Martin M. Mortazavi1,2, Syed A. Quadri1,2, Muhammad A. Khan1,2, Aaron Gustin3, Sajid S. Suriya1,2, Tania Hassanzadeh4, Kian M. Fahimdanesh5, Farzad H. Adl1,2, Salman A. Fard1,2, M. Asif Taqi1,2, Ian Armstrong1,2, Bryn A. Martin1,6, R. Shane Tubbs1,7 Key words - INTRODUCTION: Brain is suspended in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-filled sub- - Arachnoid matter arachnoid space by subarachnoid trabeculae (SAT), which are collagen- - Liliequist membrane - Microsurgical procedures reinforced columns stretching between the arachnoid and pia maters. Much - Subarachnoid trabeculae neuroanatomic research has been focused on the subarachnoid cisterns and - Subarachnoid trabecular membrane arachnoid matter but reported data on the SAT are limited. This study provides a - Trabecular cisterns comprehensive review of subarachnoid trabeculae, including their embryology, Abbreviations and Acronyms histology, morphologic variations, and surgical significance. CSDH: Chronic subdural hematoma - CSF: Cerebrospinal fluid METHODS: A literature search was conducted with no date restrictions in DBC: Dural border cell PubMed, Medline, EMBASE, Wiley Online Library, Cochrane, and Research Gate. DL: Diencephalic leaf Terms for the search included but were not limited to subarachnoid trabeculae, GAG: Glycosaminoglycan subarachnoid trabecular membrane, arachnoid mater, subarachnoid trabeculae LM: Liliequist membrane ML: Mesencephalic leaf embryology, subarachnoid trabeculae histology, and morphology. Articles with a PAC: Pia-arachnoid complex high likelihood of bias, any study published in nonpopular journals (not indexed PPAS: Potential pia-arachnoid space in PubMed or MEDLINE), and studies with conflicting data were excluded. SAH: Subarachnoid hemorrhage SAS: Subarachnoid space - RESULTS: A total of 1113 articles were retrieved. -

Spinal Cord (Sp Cd) and Nerves NERVOUS SYSTEM Functions of Nervous System

Spinal Cord (sp cd) and Nerves NERVOUS SYSTEM Functions of Nervous System 1. Collect sensory input 2. Integrate sensory input 3. Motor output Organization of Nervous System • Central Nervous System (CNS) = brain and spinal cord • Peripheral Nervous System (PNS) = nerves CNS PNS Peripheral Nervous System skin muscle Pg 344 Spinal Nerves (31 pairs) • Each pair of nerves located in particular segment (cervical, thoracic, lumbar, etc.) • Each nerve pair is numbered for the vertebra sitting above it (i.e. nerves exit below vertebrae) – 8 pairs of cervical spinal nerves; *C1-C8 – 12 pairs of thoracic spinal nerves; T1-T12 – 5 pairs of lumbar spinal nerves; L1-L5 – 5 pairs of sacral spinal nerves; S1-S5 – 1 pair of coccygeal spinal nerves; C0 Spinal Cord Segments Pg 393 Central Nervous System Pg 361 • Brain and Spinal Cord • Occupy Dorsal Cavity Meninges of Brain and Spinal Cord • Pia mater (deep) – delicate –highly vascular – adheres to brain/sp cd tissue • Arachnoid mater (middle) – impermeable layer = barrier – raised off pia mater by rootlets •Spinal Dura Mater(most superficial) – single dural sheath • Subarachnoid Space – between arachnoid and pia mater –contains CSF • Epidural Space – Between dura mater and vertebra – Contains fat and veins Pg 394 Spinal Cord (sp cd) • Passes inferiorly through foramen magnum into vertebral canal • 31 pairs of spinal nerves branch off spinal cord through intervertebral foramen • Spinal cord made of a core of gray matter surrounded by white matter Pg 393 Spinal Cord Growth •Runs from Medulla Oblongata to -

Endoscopic Third Ventriculostomy : Success and Failure

Review Article J Korean Neurosurg Soc 60 (3) : 306-314, 2017 https://doi.org/10.3340/jkns.2017.0202.013 pISSN 2005-3711 eISSN 1598-7876 Endoscopic Third Ventriculostomy : Success and Failure Chandrashekhar E. Deopujari, M.Ch., Vikram S. Karmarkar, DNB, Salman T. Shaikh, M.S. Department of Neurosurgery, Bombay Hospital Institute of Medical Science, Mumbai, India Endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV) has now become an accepted mode of hydrocephalus treatment in children. Varying degrees of success for the procedure have been reported depending on the type and etiology of hydrocephalus, age of the patient and certain technical parameters. Review of these factors for predictability of success, complications and validation of success score is presented. Key Words : Hydrocephalus · Ventriculostomy · Cerebrospinal fluid shunt. INTRODUCTION neurosurgical community to look for other solutions. This came in the form of shunts devised by Nulsen and Spitz work- Hydrocephalus is a spectrum of conditions where there is a ing with an engineer Holter in the 1950’s44). This technology mismatch of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) production and ab- was immediately accepted and has further evolved and ma- sorption, with resultant enlarged ventricles. There are many tured to become the standard of care for all types of hydro- proposed classifications for hydrocephalus. Most commonly cephalus. However, in spite of several innovations and techni- in use is the obstructive (non-communicating) and the com- cal modifications, shunts are not without complications and municating type7). In the obstructive variety, the block is have remained a constant source of concern for the child, par- proximal to the arachnoid granulations and may be further ents and the family. -

Neuroanatomy Dr

Neuroanatomy Dr. Maha ELBeltagy Assistant Professor of Anatomy Faculty of Medicine The University of Jordan 2018 Prof Yousry 10/15/17 A F B K G C H D I M E N J L Ventricular System, The Cerebrospinal Fluid, and the Blood Brain Barrier The lateral ventricle Interventricular foramen It is Y-shaped cavity in the cerebral hemisphere with the following parts: trigone 1) A central part (body): Extends from the interventricular foramen to the splenium of corpus callosum. 2) 3 horns: - Anterior horn: Lies in the frontal lobe in front of the interventricular foramen. - Posterior horn : Lies in the occipital lobe. - Inferior horn : Lies in the temporal lobe. rd It is connected to the 3 ventricle by body interventricular foramen (of Monro). Anterior Trigone (atrium): the part of the body at the horn junction of inferior and posterior horns Contains the glomus (choroid plexus tuft) calcified in adult (x-ray&CT). Interventricular foramen Relations of Body of the lateral ventricle Roof : body of the Corpus callosum Floor: body of Caudate Nucleus and body of the thalamus. Stria terminalis between thalamus and caudate. (connects between amygdala and venteral nucleus of the hypothalmus) Medial wall: Septum Pellucidum Body of the fornix (choroid fissure between fornix and thalamus (choroid plexus) Relations of lateral ventricle body Anterior horn Choroid fissure Relations of Anterior horn of the lateral ventricle Roof : genu of the Corpus callosum Floor: Head of Caudate Nucleus Medial wall: Rostrum of corpus callosum Septum Pellucidum Anterior column of the fornix Relations of Posterior horn of the lateral ventricle •Roof and lateral wall Tapetum of the corpus callosum Optic radiation lying against the tapetum in the lateral wall.