(Ipss) Regulating Proliferation and M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Oobb O O O O

Tigray, Afar, Amhara and Benishangul - Hot Spot Map 03 August 2010 AWD, M easles and M alaria Measles, malaria and AWD cases Eritrea Legend con tin ue to be reported by FMoH . R Durin g the cou rse of the reportin g !ª International Boundary E week, 1 ,016 cases of m easles with !ª W !ª !ª D Regional Boundary no fata lities were reported from Ahferom SNNPR and 107 cases from Oromia. Tahtay Erob Laelay !ª W Gulomekeda S Zonal Boundary Betwee n 5 an d 11 July, MoH has !ª Adiyabo Adiyabo Mereb Leke !ª E > W N repo rted 24 ne w cases (n one fa tal) Tahtay Maychew " B A Woreda Boundary of AWD fro m Oro mia (1 in Aba ya ; 2 !Ò North Western Adwa Ganta Afeshum 7 Dalul in Ga lan a); S omali (13 in Jijig a) a nd Tahtay N Saesie Tsaedaemba !ª Lakes N > B SNNPR (2 in Yirgachefe; 6 in Kuchere). Kafta Humera W Koraro B Werei W Eastern Asgede Tsimbila W N Leke Hot Spot Areas Naeder Adet B W Berahle > Western BN W BN BN No Data/No Humanitarian Concern BN Kola Kelete Awelallo N W W Temben Close Monitoring B Tselemti Zone 2 > CentralW N !ª Medium Humanitarian Concern Tselemt B Addi N W Tanqua Abergele N B W Ab Afdera Critical BArekay Beyeda N b B N Ala obb b Sudan Debark Abergele B o N W > Saharti W Hot Spot Indicators -- This month N B N > Southern N B W B Samre W Megale B Bidu Dabat Janamora > > W N " AWD " Malaria "Measles Sahla N Alaje b N N B B b > B> N W B N b o N Wegera B bo > > Flood ¼¤¼Armyworm North Gonder B Ziquala Endamehoni B N N N Sekota Raya W B B N B 7 Refugees/IDPs Fire Incidents > Wag Himra N !Ò >B East B Azebo Yalo Teru !ª bb > Ofla W Kurri > Water Shortage/WASH related concerns N Belesa W B W W > N > Dembia Dehana W B Zone 4 > > Alamata W Food Insecurity N High Malnutrition W N B Gonder Zuria N W !ª Elidar Ebenat B N bb B Libo Kemkem B Gulina La nd s l id e W Bugna W o J Land Slide !ª Border Conflict Kobo Lasta Gidan N N W B N Livestock Livestock Disease/ B (Ayna) bb Ewa BN B Fogera N Migration Lay W o Mortality due to drought Meket B N Zone 1 o Gayint N North Wollo B Dubti B N b Chifra Appro x. -

Yellow Rust (Puccinia Striiformis) Epidemics and Yield Loss Assessment on Wheat and Triticale Crops in Amhara Region, Ethiopia

International Scholars Journals African Journal of Crop Science ISSN 2375-1231 Vol. 4 (2), pp. 280-285, February, 2016. Available online at www.internationalscholarsjournals.org © International Scholars Journals Author(s) retain the copyright of this article. Full Length Research Paper Yellow rust (Puccinia striiformis) epidemics and yield loss assessment on wheat and triticale crops in Amhara region, Ethiopia Landuber Wendale1, Habtamu Ayalew*2, Getaneh Woldeab3, Girma Mulugeta4 1Amhara Regional Agricultural Research Institute, Adet Agricultural Research Centre, P.O.Box 8, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. 2Debre Markos University, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, P.O.Box 269, Debre Markos, Ethiopia. 3Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research, Ambo Plant Protection Research Centre, P. O. Box 37 Ambo, Ethiopia. 4Amhara Regional Bureau of Agriculture, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. Accepted 09 October, 2015 The impact of yellow rust on grain yield and thousand grains weight was assessed by superimposing trials on farmer’s fields in three administrative zones in Amhara region. Paired (fungicide sprayed and unsprayed) plots with two replications were used in three districts with three localities each. Yellow rust resulted in a significant (P<0.05) reduction in grain yield (34%) and thousand seed weight (16.7 %) in the region. Grain yield losses of 47.2% and 32% were observed in the worst scenario in north Shewa and in east Gojam zones, respectively. Grain yield loss was lowest (28%) for south Gondar zone. The wheat cultivars suffered the highest yield and seed weight reductions as compared to triticale. Grain yield reductions of 41.5% and 43.6% were recorded on cultivars HAR 1685 and HAR 604, respectively while the triticale cultivar, Logaw Shibo showed a 23.8% reduction. -

Ethiopia: Amhara Region Administrative Map (As of 05 Jan 2015)

Ethiopia: Amhara region administrative map (as of 05 Jan 2015) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Abrha jara ! Tselemt !Adi Arikay Town ! Addi Arekay ! Zarima Town !Kerakr ! ! T!IGRAY Tsegede ! ! Mirab Armacho Beyeda ! Debark ! Debarq Town ! Dil Yibza Town ! ! Weken Town Abergele Tach Armacho ! Sanja Town Mekane Berhan Town ! Dabat DabatTown ! Metema Town ! Janamora ! Masero Denb Town ! Sahla ! Kokit Town Gedebge Town SUDAN ! ! Wegera ! Genda Wuha Town Ziquala ! Amba Giorges Town Tsitsika Town ! ! ! ! Metema Lay ArmachoTikil Dingay Town ! Wag Himra North Gonder ! Sekota Sekota ! Shinfa Tomn Negade Bahr ! ! Gondar Chilga Aukel Ketema ! ! Ayimba Town East Belesa Seraba ! Hamusit ! ! West Belesa ! ! ARIBAYA TOWN Gonder Zuria ! Koladiba Town AMED WERK TOWN ! Dehana ! Dagoma ! Dembia Maksegnit ! Gwehala ! ! Chuahit Town ! ! ! Salya Town Gaz Gibla ! Infranz Gorgora Town ! ! Quara Gelegu Town Takusa Dalga Town ! ! Ebenat Kobo Town Adis Zemen Town Bugna ! ! ! Ambo Meda TownEbinat ! ! Yafiga Town Kobo ! Gidan Libo Kemkem ! Esey Debr Lake Tana Lalibela Town Gomenge ! Lasta ! Muja Town Robit ! ! ! Dengel Ber Gobye Town Shahura ! ! ! Wereta Town Kulmesk Town Alfa ! Amedber Town ! ! KUNIZILA TOWN ! Debre Tabor North Wollo ! Hara Town Fogera Lay Gayint Weldiya ! Farta ! Gasay! Town Meket ! Hamusit Ketrma ! ! Filahit Town Guba Lafto ! AFAR South Gonder Sal!i Town Nefas mewicha Town ! ! Fendiqa Town Zege Town Anibesema Jawi ! ! ! MersaTown Semen Achefer ! Arib Gebeya YISMALA TOWN ! Este Town Arb Gegeya Town Kon Town ! ! ! ! Wegel tena Town Habru ! Fendka Town Dera -

AMHARA Demography and Health

1 AMHARA Demography and Health Aynalem Adugna January 1, 2021 www.EthioDemographyAndHealth.Org 2 Amhara Suggested citation: Amhara: Demography and Health Aynalem Adugna January 1, 20201 www.EthioDemographyAndHealth.Org Landforms, Climate and Economy Located in northwestern Ethiopia the Amhara Region between 9°20' and 14°20' North latitude and 36° 20' and 40° 20' East longitude the Amhara Region has an estimated land area of about 170000 square kilometers . The region borders Tigray in the North, Afar in the East, Oromiya in the South, Benishangul-Gumiz in the Southwest and the country of Sudan to the west [1]. Amhara is divided into 11 zones, and 140 Weredas (see map at the bottom of this page). There are about 3429 kebeles (the smallest administrative units) [1]. "Decision-making power has recently been decentralized to Weredas and thus the Weredas are responsible for all development activities in their areas." The 11 administrative zones are: North Gonder, South Gonder, West Gojjam, East Gojjam, Awie, Wag Hemra, North Wollo, South Wollo, Oromia, North Shewa and Bahir Dar City special zone. [1] The historic Amhara Region contains much of the highland plateaus above 1500 meters with rugged formations, gorges and valleys, and millions of settlements for Amhara villages surrounded by subsistence farms and grazing fields. In this Region are located, the world- renowned Nile River and its source, Lake Tana, as well as historic sites including Gonder, and Lalibela. "Interspersed on the landscape are higher mountain ranges and cratered cones, the highest of which, at 4,620 meters, is Ras Dashen Terara northeast of Gonder. -

114596989.Pdf (1.092Mb)

Food Security, Gender and Community Relations. Challenges and Strategies of Rural Women in Goncha Siso Enese Woreda, Ethiopia, and the Role of the Productive Safety Net Programme in Empowering Women. Addis Bezabih Mekonnen MASTER THESIS M.Phil programme in Gender and Development Autumn 2013 Faculty of Psychology Department of Health Promotion and Development DECLARATION I, the undersigned student declare that this is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other university and that all sources of materials used in this thesis have been duly acknowledged. Addis Bezabih November 19, 2013 Acknowledgements I am thankful all of those people who supported me in any respect during my study. I am particularly thankful to my supervisor, Haldis Haukanes, who offered invaluable assistance and guidance from the beginning to the final level of the study. Your substantial and constructive comments were of paramount significance in shaping this study. I am greatly indebted to my families especially my husband Hiowte and my brother Mulugeta who support me in all aspects. I also want to thank all the people who participated in this study and the staff of Goncha Siso Enese Woreda Administration and Office of Agriculture and Rural Development for their willingness and support they provided me in collecting the data. Last but not least; I am eternally grateful to thank my GAD friends i List of Acronyms ACSA Amhara Credit and Saving Association ADE Administrative Division of Ethiopia ADLI Agriculture Development Led Industrialization -

Demography and Health

1 AMHARA Demography and Health Aynalem Adugna July, 2014 www.EthioDemographyAndHealth.Org 2 Landforms, Climate and Economy Located in northwestern Ethiopia the Amhara Region between 9°20' and 14°20' North latitude and 36° 20' and 40° 20' East longitude the Amhara Region has an estimated land area of about 170000 square kilometers . The region borders Tigray in the North, Afar in the East, Oromiya in the South, Benishangul-Gumiz in the Southwest and the country of Sudan to the west [1]. Amhara is divided into 11 zones, and 140 Weredas (see map at the bottom of this page). There are about 3429 kebeles (the smallest administrative units) [1]. "Decision-making power has recently been decentralized to Weredas and thus the Weredas are responsible for all development activities in their areas." The 11 administrative zones are: North Gonder, South Gonder, West Gojjam, East Gojjam, Awie, Wag Hemra, North Wollo, South Wollo, Oromia, North Shewa and Bahir Dar City special zone. [1] The historic Amhara Region contains much of the highland plateaus above 1500 meters with rugged formations, gorges and valleys, and millions of settlements for Amhara villages surrounded by subsistence farms and grazing fields. In this Region are located, the world- renowned Nile River and its source, Lake Tana, as well as historic sites including Gonder, and Lalibela. "Interspersed on the landscape are higher mountain ranges and cratered cones, the highest of which, at 4,620 meters, is Ras Dashen Terara northeast of Gonder. ….Millennia of erosion has produced steep valleys, in places 1,600 meters deep and several kilometers wide. -

Download File

Report One size does not fit all The patterning and drivers of child marriage in Ethiopia’s hotspot districts Nicola Jones, Bekele Tefera, Guday Emirie, Bethelihem Gebre, Kiros Berhanu, Elizabeth Presler-Marshall, David Walker, Taveeshi Gupta and Georgia Plank March 2016 This research was conducted by Overseas Development Institute (ODI), contracted by UNICEF in collaboration with the National Alliance to End Child Marriage and FGM in Ethiopia by 2025. UNICEF and ODI hold joint copyright. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the policies or views of UNICEF or ODI. UNICEF Ethiopia UNECA Compound, Zambezi Building Tel: +251115184000 Fax: +251115511628 E-mail:[email protected] www.unicef.org/Ethiopia Overseas Development Institute 203 Blackfriars Road London SE1 8NJ Tel. +44 (0) 20 7922 0300 Fax. +44 (0) 20 7922 0399 E-mail: [email protected] www.odi.org www.odi.org/facebook www.odi.org/twitter Readers are encouraged to reproduce material from ODI Reports for their own publications, as long as they are not being sold commercially. As copyright holder, ODI and UNICEF request due acknowledgement and a copy of the publication. For online use, we ask readers to link to the original resource on the ODI and UNICEF websites. © Overseas Development Institute and United Nations Children’s Fund 2015. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial Licence (CC BY-NC 3.0). ISSN: 2052-7209 All ODI Reports are available from www.odi.org Cover photo: Hands, Ethiopia -

Archival Management and Preservation in Ethiopia: the Case of East Gojjam

ACCESS Freely available online urism & OPEN o H f T o o s l p a i t n a r l i u t y o J Journal of ISSN: 2167-0269 Tourism & Hospitality Research Article Archival Management and Preservation in Ethiopia: The Case of East Gojjam Solomon Ashagrie Chekole1*, Fekede Bekele2 and Beyene Chekol2 1Department of History and Heritage Management, Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia; 2Department of History and Heritage Management, Debre Markos University, Ethiopia ABSTRACT Archives are the literary heritages of societies which can serve as testimony of the past activities and events. Due to this high value they need to be carefully selected and preserved to prevent destruction. Ethiopia is among few African countries which have many written documents about its history which dates back thousands of years. In East Gojjam Administrative Zone there are many archives which were produced after the beginning of modern bureaucracy particularly in the post 1941 period. However the management and preservation of these archives in the area is destructive. This paper aims to investigate the management and preservation of archives from their creation as a record to their final retirement. Descriptive study design was used and data was collected through observation, interview and document analysis including archives. The research finding shows that archives of East Gojjam Administrative Zone are not properly handled and so they are deteriorating continuously. The researchers strongly argue that archives do not get recognition as heritage by different stakeholders in the area and so the record and archive management system should be reconsidered. Keywords: Archive; Record; Preservation INTRODUCTION sources to write the history of colonialism in many African countries. -

The Development Study on the Improvement of Livelihood Through Integrated Watershed Management in Amhara Region

Food Security Coordination & Disaster Prevention Office Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Development The Government of Amhara National Regional State The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia THE DEVELOPMENT STUDY ON THE IMPROVEMENT OF LIVELIHOOD THROUGH INTEGRATED WATERSHED MANAGEMENT IN AMHARA REGION FINAL REPORT March 2011 Japan International Cooperation Agency SANYU CONSULTANTS INC. ETO JR 11-002 Location map Location Map of the Study Area FINAL REPORT Summary 1. INTRODUCTION OF THE STUDY Amhara National Regional State (ANRS) located in the northern part of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia has the area of about 154 thousand sq. km. accounting for around 15% of the territory of the nation where about 17.9 million (or about 25% of the national population) are inhabited. In the ANRS, 6.3 million people are considered as food insecure. In particular, the eastern area of Amhara Region has been exposed to recurrent drought for past 3 decades, thus considered as the most suffering area from food shortage. Under such circumstances, the Federal Government of Ethiopia requested cooperation of Japan for “The Development Study on the Improvement of Livelihood through Integrated Watershed Management in Amhara Region”. Based on this request, Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) dispatched a preparatory study team to Ethiopia in March 2007 and agreed the basic contents of Scope of Work (S/W) that were signed between the ANRS Government and JICA in the same month. Under such background, JICA dispatched a Study Team to the ANRS from March 2008 to conduct the Study as described in the S/W. The overall goal of the Study is to ensure food security of the vulnerable households in food insecure area of Amhara Region through implementation of integrated watershed management. -

Wind Energy Data Analysis and Resource Mapping of East Gojjam Zone, Amhara Region

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 10, Issue 3, March-2019 ISSN 2229-5518 1455 Wind Energy Data Analysis and Resource Mapping of East Gojjam Zone, Amhara Region Addisu Dagne1, Aynalem Worku2 1 Lecturer, School of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, Institute of Technology, Debre Markos University, Ethiopia, [email protected] 2 Lecturer, Department of Mechanical Engineering, College of Engineering and Technology, Aksum University, Ethiopia, [email protected] Abstract - Knowledge of wind energy regime is a pre-requisite for any wind energy planning and implementation projects. The wind energy potential of Ethiopia is estimated to be about 10,000MW, but only less than 8 percent of it is utilized so far. One of the reasons for this low utilization of wind energy in Ethiopia is absence of a reliable and accurate wind atlas. Development of reliable and accurate wind atlas helps to identify candidate sites for wind energy applications and facilitates the planning and implementation of wind energy projects. The main purpose of this research project is to analyze the available wind energy data in East Gojjam Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia and develop a resource map which could help planners, potential investors and researchers in identifying potential area for wind energy applications in the zone. In this research project wind data collected over a period of two years from Debre Markos and Motta metrological stations was analyzed using different statistical software like Excel, WindRosePRO3 and MATLAB to evaluate the wind energy potential of the area. Average wind speed and power density, distributionIJSER of the wind, prevailing direction, turbulence intensity and wind shear profile of each site were determined. -

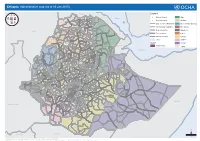

Ethiopia: Administrative Map (As of 05 Jan 2015)

Ethiopia: Administrative map (as of 05 Jan 2015) ERITREA Legend Ahferom Erob ^! Tahtay Adiyabo National Capital Gulomekeda Afar Laelay Adiyabo Mereb Leke Red Sea Dalul Ganta Afeshum P! Adwa SaesEiea Tsatedranemba Regional Capital Amhara North WesternTahtay KoraroLaelay Maychew Kafta Humera Tahtay Maychew Werei Leke Hawzen Asgede Tsimbila Central Koneba TIGRAY Medebay Zana Naeder Adet Berahile Western Atsbi Wenberta Undetermined boundary Beneshangul Gumuz Kelete Awelallo Welkait Kola Temben Tselemti Degua Temben Mekele P! Zone 2 International boundary Dire Dawa Tsegede Tselemt Enderta Tanqua Abergele Afdera Addi Arekay Ab Ala Tsegede Beyeda Mirab Armacho Afdera Region boundary Gambela Debark Saharti Samre Erebti Hintalo Wejirat SUDAN Abergele Tach Armacho Dabat Janamora Megale Bidu Alaje Sahla Southern Zone boundary Hareri Ziquala Raya Azebo Metema Lay Armacho Wegera Wag Himra Endamehoni North Gonder Sekota Teru Chilga Woreda boundary Oromia Yalo East Belesa Ofla West Belesa Kurri Dehana Dembia Gonder Zuria Alamata Zone 4 Elidar Gaz Gibla Lake SNNPR Quara Takusa Ebenat Gulina Libo Kemkem Bugna Awra Kobo Tana Gidan Region Lasta (Ayna) AFAR Somali Alfa Ewa Fogera Farta North Wollo Semera Lay Gayint Meket Guba Lafto P! Dubti Zone 1 DJIBOUTI Addis Ababa Jawi Semen Achefer South Gonder Tigray East Esite Chifra Bahir Dar Wadla Habru Aysaita AMHARA P! Dera Tach Gayint Delanta Guba Bahirdar Zuria Ambasel Debub Achefer Dawunt Worebabu Dangura Gulf of Aden Mecha West Esite Simada Thehulederie Adaa'r Mile Pawe Special Afambo Dangila Kutaber Yilmana