Smooth Greensnake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blackwater NWR Reptiles and Amphibians List

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge 2145 Key Wallace Dr. Cambridge, MD 21613 410/228 2677 Fax: 410/221 7738 Blackwater Email: [email protected] http://www.fws.gov/blackwater/ National Wildlife U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service http://www.fws.gov Refuge For Refuge Information 1 800/344 WILD Reptiles & Amphibians Federal Relay Service for the deaf and hard-of-hearing 1 800/877 8339 Voice and TTY July 2008 NT OF E TH TM E R IN A P T E E R D I . O S R . U M A 49 RC H 3, 18 Northern Redbelly Turtle Rachel Woodward/ USFWS Reptiles The vast marshes and Reptiles are cold-blooded vertebrates including turtles, snakes and lizards. Reptiles are characterized by bodies bordering swamps of with dry skin (not slimy) and scales, Blackwater National or scutes. They usually lay eggs. Turtles Northern Redbelly Turtle Wildlife Refuge offer (Pseudemys rubriventris), Common, 10-12.5". Has a smooth, elongated shell that is olive-brown to black with ideal living conditions red vertical forked lines. Prefers larger bodies of fresh water and for an array of reptiles basks like the smaller painted turtle. and amphibians. These Largely vegetarian. Eastern Painted Turtle (Chrysemys p. picta), Common, cold-blooded animals 4-7". The most visible turtle on the refuge can be seen in the summer become dormant in and fall basking on logs in both fresh and brackish water. Has a smooth, flattened, olive to black shell with winter, but as spring yellow borders on seams. Limbs and tail are black with red stripes. -

Venomous Snakes in Pennsylvania the First Question Most People Ask When They See a Snake Is “Is That Snake Poisonous?” Technically, No Snake Is Poisonous

Venomous Snakes in Pennsylvania The first question most people ask when they see a snake is “Is that snake poisonous?” Technically, no snake is poisonous. A plant or animal that is poisonous is toxic when eaten or absorbed through the skin. A snake’s venom is injected, so snakes are classified as venomous or nonvenomous. In Pennsylvania, we have only three species of venomous snakes. They all belong to the pit viper Nostril family. A snake that is a pit viper has a deep pit on each side of its head that it uses to detect the warmth of nearby prey. This helps the snake locate food, especially when hunting in the darkness of night. These Pit pits can be seen between the eyes and nostrils. In Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Snakes all of our venomous Checklist snakes have slit-like A complete list of Pennsylvania’s pupils that are 21 species of snakes. similar to a cat’s eye. Venomous Nonvenomous Copperhead (venomous) Nonvenomous snakes Eastern Garter Snake have round pupils, like a human eye. Eastern Hognose Snake Eastern Massasauga (venomous) Venomous If you find a shedded snake Eastern Milk Snake skin, look at the scales on the Eastern Rat Snake underside. If they are in a single Eastern Ribbon Snake Eastern Smooth Earth Snake row all the way to the tip of its Eastern Worm Snake tail, it came from a venomous snake. Kirtland’s Snake If the scales split into a double row Mountain Earth Snake at the tail, the shedded skin is from a Northern Black Racer Nonvenomous nonvenomous snake. -

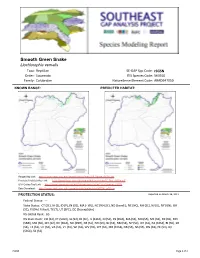

Smooth Green Snake

Smooth Green Snake Liochlorophis vernalis Taxa: Reptilian SE-GAP Spp Code: rSGSN Order: Squamata ITIS Species Code: 563910 Family: Colubridae NatureServe Element Code: ARADB47010 KNOWN RANGE: PREDICTED HABITAT: P:\Proj1\SEGap P:\Proj1\SEGap Range Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Range_rSGSN.pdf Predicted Habitat Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Dist_rSGSN.pdf GAP Online Tool Link: http://www.gapserve.ncsu.edu/segap/segap/index2.php?species=rSGSN Data Download: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/region/vert/rSGSN_se00.zip PROTECTION STATUS: Reported on March 14, 2011 Federal Status: --- State Status: CT (SC), IA (S), ID (P), IN (SE), MA (- WL), NC (W4,SC), ND (Level I), NE (NC), NH (SC), NJ (U), NY (GN), OH (SC), RI (Not Listed), TX (T), UT (SPC), QC (Susceptible) NS Global Rank: G5 NS State Rank: CO (S4), CT (S3S4), IA (S3), ID (SH), IL (S3S4), IN (S2), KS (SNA), MA (S5), MD (S5), ME (S5), MI (S5), MN (SNR), MO (SX), MT (S2), NC (SNA), ND (SNR), NE (S1), NH (S3), NJ (S3), NM (S4), NY (S4), OH (S4), PA (S3S4), RI (S5), SD (S4), TX (S1), UT (S2), VA (S3), VT (S3), WI (S4), WV (S5), WY (S2), MB (S3S4), NB (S5), NS (S5), ON (S4), PE (S3), QC (S3S4), SK (S3) rSGSN Page 1 of 4 SUMMARY OF PREDICTED HABITAT BY MANAGMENT AND GAP PROTECTION STATUS: US FWS US Forest Service Tenn. Valley Author. US DOD/ACOE ha % ha % ha % ha % Status 1 0.0 0 17.6 < 1 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 2 0.0 0 1,117.9 < 1 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 3 0.0 0 6,972.8 1 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 4 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Total 0.0 0 8,108.3 2 0.0 0 0.0 0 US Dept. -

Amphibians & Reptiles

AmphibiansAmphibians && ReptilesReptiles onon thethe NiagaraNiagara EscarpmentEscarpment By Fiona Wagner For anyone fortunate enough to be hiking the Bruce Trail in the early spring, it can be an overwhelming and humbling experience. That’s when the hills awaken to the resounding sound of frogs - the Wood frogs come first, followed by the Spring Peepers and Spiny Softshell Turtle Chrous frogs. By summer, seven more species will have joined this wondrous and sometimes deafening cacophony and like instruments in 15 an orchestra, each one has their unique call. Photo: Don Scallen Bruce Trail Magazine Spring 2010 Photo: Gary Hall Like an oasis in a desert of urban Toronto Zoo. “It’s this sheer diversi- of some of these creatures can be an development, the Niagara ty and the density of some of these astonishing experience, says Don Escarpment is home to more than experiences. I’m hooked for that Scallen, a teacher and vice president 30 reptiles and amphibians, includ- reason. You’ll never know what of Halton North Peel Naturalist ing several at risk species such as the you’re going to find.” Club. Don hits the Trail in early Dusky Salamander and Spotted spring to watch the rare and local Turtle (both endangered) as well as When and where to go Jefferson salamanders and their the threatened Jefferson Salamander. While it’s possible to see amphib- more common relative, the Yellow It is the diversity of the escarpment’s ians and reptiles from March to Spotted salamander. varied habitats, including wetlands, October, you’ll have more success if “A good night for salamander rocky outcrops and towering old you think seasonally, says Johnson. -

Wildlife in Your Young Forest.Pdf

WILDLIFE IN YOUR Young Forest 1 More Wildlife in Your Woods CREATE YOUNG FOREST AND ENJOY THE WILDLIFE IT ATTRACTS WHEN TO EXPECT DIFFERENT ANIMALS his guide presents some of the wildlife you may used to describe this dense, food-rich habitat are thickets, T see using your young forest as it grows following a shrublands, and early successional habitat. timber harvest or other management practice. As development has covered many acres, and as young The following lists focus on areas inhabited by the woodlands have matured to become older forest, the New England cottontail (Sylvilagus transitionalis), a rare amount of young forest available to wildlife has dwindled. native rabbit that lives in parts of New York east of the Having diverse wildlife requires having diverse habitats on Hudson River, and in parts of Connecticut, Rhode Island, the land, including some young forest. Massachusetts, southern New Hampshire, and southern Maine. In this region, conservationists and landowners In nature, young forest is created by floods, wildfires, storms, are carrying out projects to create the young forest and and beavers’ dam-building and feeding. To protect lives and shrubland that New England cottontails need to survive. property, we suppress floods, fires, and beaver activities. Such projects also help many other kinds of wildlife that Fortunately, we can use habitat management practices, use the same habitat. such as timber harvests, to mimic natural disturbance events and grow young forest in places where it will do the most Young forest provides abundant food and cover for insects, good. These habitat projects boost the amount of food reptiles, amphibians, birds, and mammals. -

References for Life History

Literature Cited Adler, K. 1979. A brief history of herpetology in North America before 1900. Soc. Study Amphib. Rept., Herpetol. Cir. 8:1-40. 1989. Herpetologists of the past. In K. Adler (ed.). Contributions to the History of Herpetology, pp. 5-141. Soc. Study Amphib. Rept., Contrib. Herpetol. no. 5. Agassiz, L. 1857. Contributions to the Natural History of the United States of America. 2 Vols. Little, Brown and Co., Boston. 452 pp. Albers, P. H., L. Sileo, and B. M. Mulhern. 1986. Effects of environmental contaminants on snapping turtles of a tidal wetland. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol, 15:39-49. Aldridge, R. D. 1992. Oviductal anatomy and seasonal sperm storage in the southeastern crowned snake (Tantilla coronata). Copeia 1992:1103-1106. Aldridge, R. D., J. J. Greenshaw, and M. V. Plummer. 1990. The male reproductive cycle of the rough green snake (Opheodrys aestivus). Amphibia-Reptilia 11:165-172. Aldridge, R. D., and R. D. Semlitsch. 1992a. Female reproductive biology of the southeastern crowned snake (Tantilla coronata). Amphibia-Reptilia 13:209-218. 1992b. Male reproductive biology of the southeastern crowned snake (Tantilla coronata). Amphibia-Reptilia 13:219-225. Alexander, M. M. 1943. Food habits of the snapping turtle in Connecticut. J. Wildl. Manag. 7:278-282. Allard, H. A. 1945. A color variant of the eastern worm snake. Copeia 1945:42. 1948. The eastern box turtle and its behavior. J. Tenn. Acad. Sci. 23:307-321. Allen, W. H. 1988. Biocultural restoration of a tropical forest. Bioscience 38:156-161. Anonymous. 1961. Albinism in southeastern snakes. Virginia Herpetol. Soc. Bull. -

Changes in Snake Abundance After 21 Years in Southwest Florida, USA

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 14(1):31–40. Submitted: 16 November 2017; Accepted: 12 February 2019; Published: 30 April 2019. CHANGES IN SNAKE ABUNDANCE AFTER 21 YEARS IN SOUTHWEST FLORIDA, USA DEAN A. CROSHAW1,3, JOHN R. CASSANI2, ELI V. BACHER1, TAYLOR L. HANCOCK2, 2 AND EDWIN M. EVERHAM III 1Florida Gulf Coast University, Department of Biological Sciences, Fort Myers, Florida 33965, USA 2Florida Gulf Coast University, Department of Marine and Ecological Sciences, Fort Myers, Florida 33965, USA 3Corresponding author, e–mail: [email protected] Abstract.—Global population declines in herpetofauna have been documented extensively. Southern Florida, USA, is an especially vulnerable region because of high impacts from land development, associated hydrological alterations, and invasive exotic species. To ask whether certain snake species have decreased in abundance over recent decades, we performed a baseline road survey in 1993–1994 in a rural area of southwest Florida (Lee County) and repeated it 21 y later (2014–2015). We sampled a road survey route (17.5 km) for snakes by bicycle an average of 1.3 times a week (n = 45 surveys) from June 1993 through January 1994 and 1.7 times a week from June 2014 through January 2015 (n = 61 surveys). Snake mortality increased significantly after 21 y, but this result may be due to increased road traffic rather than expanding snake populations. The snake samples were highly dissimilar in the two periods, suggesting changes in species composition. For example, one species showed a highly significant decrease in abundance (Rough Greensnake, Opheodrys aestivus) while another showed substantial increases (Ring-necked Snake, Diadophis punctatus). -

Plymouth Produced in 2012

BioMap2 CONSERVING THE BIODIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS IN A CHANGING WORLD Plymouth Produced in 2012 This report and associated map provide information about important sites for biodiversity conservation in your area. This information is intended for conservation planning, and is not intended for use in state regulations. BioMap2 Conserving the Biodiversity of Massachusetts in a Changing World Table of Contents Introduction What is BioMap2 Ȯ Purpose and applications One plan, two components Understanding Core Habitat and its components Understanding Critical Natural Landscape and its components Understanding Core Habitat and Critical Natural Landscape Summaries Sources of Additional Information Plymouth Overview Core Habitat and Critical Natural Landscape Summaries Elements of BioMap2 Cores Core Habitat Summaries Elements of BioMap2 Critical Natural Landscapes Critical Natural Landscape Summaries Natural Heritage Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife 1 Rabbit Hill Road, Westborough, MA 01581 & Endangered phone: 508-389-6360 fax: 508-389-7890 Species Program For more information on rare species and natural communities, please see our fact sheets online at www.mass.gov/nhesp. BioMap2 Conserving the Biodiversity of Massachusetts in a Changing World Introduction The Massachusetts Department of Fish & Game, ɳɧɱɮɴɦɧ ɳɧɤ Dɨɵɨɲɨɮɭ ɮɥ Fɨɲɧɤɱɨɤɲ ɠɭɣ Wɨɫɣɫɨɥɤ˘ɲ Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP), and The Nature Cɮɭɲɤɱɵɠɭɢɸ˘ɲ Mɠɲɲɠɢɧɴɲɤɳɳɲ Pɱɮɦɱɠɬ developed BioMap2 ɳɮ ɯɱɮɳɤɢɳ ɳɧɤ ɲɳɠɳɤ˘ɲ biodiversity in the context of climate change. BioMap2 ɢɮɬɡɨɭɤɲ NHESP˘ɲ ȯȬ ɸɤɠɱɲ ɮɥ rigorously documented rare species and natural community data with spatial data identifying wildlife species and habitats that were the focus ɮɥ ɳɧɤ Dɨɵɨɲɨɮɭ ɮɥ Fɨɲɧɤɱɨɤɲ ɠɭɣ Wɨɫɣɫɨɥɤ˘ɲ ȮȬȬȱ State Wildlife Action Plan (SWAP). -

PDF Files Before Requesting Examination of Original Lication (Table 2)

often be ingested at night. A subsequent study on the acceptance of dead prey by snakes was undertaken by curator Edward George Boulenger in 1915 (Proc. Zool. POINTS OF VIEW Soc. London 1915:583–587). The situation at the London Zoo becomes clear when one refers to a quote by Mitchell in 1929: “My rule about no living prey being given except with special and direct authority is faithfully kept, and permission has to be given in only the rarest cases, these generally of very delicate or new- Herpetological Review, 2007, 38(3), 273–278. born snakes which are given new-born mice, creatures still blind and entirely un- © 2007 by Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles conscious of their surroundings.” The Destabilization of North American Colubroid 7 Edward Horatio Girling, head keeper of the snake room in 1852 at the London Zoo, may have been the first zoo snakebite victim. After consuming alcohol in Snake Taxonomy prodigious quantities in the early morning with fellow workers at the Albert Public House on 29 October, he staggered back to the Zoo and announced that he was inspired to grab an Indian cobra a foot behind its head. It bit him on the nose. FRANK T. BURBRINK* Girling was taken to a nearby hospital where current remedies available at the time Biology Department, 2800 Victory Boulevard were tried: artificial respiration and galvanism; he died an hour later. Many re- College of Staten Island/City University of New York spondents to The Times newspaper articles suggested liberal quantities of gin and Staten Island, New York 10314, USA rum for treatment of snakebite but this had already been accomplished in Girling’s *Author for correspondence; e-mail: [email protected] case. -

Indiana County Endangered, Threatened and Rare Species List 03/09/2020 County: Brown

Page 1 of 2 Indiana County Endangered, Threatened and Rare Species List 03/09/2020 County: Brown Species Name Common Name FED STATE GRANK SRANK Mollusk: Bivalvia (Mussels) Villosa lienosa Little Spectaclecase SSC G5 S3 Insect: Coleoptera (Beetles) Cicindela patruela A Tiger Beetle SR G3 S3 Insect: Lepidoptera (Butterflies & Moths) Autochton cellus Gold-banded Skipper SE G4 S1 Hyperaeschra georgica A Prominent Moth ST G5 S2 Insect: Odonata (Dragonflies & Damselflies) Rhionaeschna mutata Spatterdock Darner ST G4 S2S3 Tachopteryx thoreyi Gray Petaltail WL G4 S3 Amphibian Acris blanchardi Blanchard's Cricket Frog SSC G5 S4 Reptile Clonophis kirtlandii Kirtland's Snake SE G2 S2 Crotalus horridus Timber Rattlesnake SE G4 S2 Opheodrys aestivus Rough Green Snake SSC G5 S3 Opheodrys vernalis Smooth Green Snake SE G5 S2 Terrapene carolina carolina Eastern Box Turtle SSC G5T5 S3 Bird Accipiter striatus Sharp-shinned Hawk SSC G5 S2B Aimophila aestivalis Bachman's Sparrow G3 SXB Ammodramus henslowii Henslow's Sparrow SE G4 S3B Antrostomus vociferus Whip-poor-will SSC G5 S4B Buteo platypterus Broad-winged Hawk SSC G5 S3B Cistothorus platensis Sedge Wren SE G5 S3B Dendroica virens Black-throated Green Warbler G5 S2B Haliaeetus leucocephalus Bald Eagle SSC G5 S2 Helmitheros vermivorus Worm-eating Warbler SSC G5 S3B Ixobrychus exilis Least Bittern SE G4G5 S3B Mniotilta varia Black-and-white Warbler SSC G5 S1S2B Setophaga cerulea Cerulean Warbler SE G4 S3B Setophaga citrina Hooded Warbler SSC G5 S3B Mammal Lasiurus borealis Eastern Red Bat SSC G3G4 S4 -

CFC Helping Fund Restoration of Smooth Green Snake to Greenway

CFC Citizens for Conservation Saving Living Space for Living Things NEWVol. 36, No. 1, SpringS 2017 CFC helping fund restoration of smooth green snake to Greenway corridor habitat by Tom Vanderpoel The best way to increase biodiversity for all these native species and many more that didn’t make the list is to expand their habitats. Citizens for Conservation (CFC)’s new Barrington Greenway This is what the Barrington Greenway Initiative will do. Join us in Initiative is moving forward on several fronts. our efforts. This will take several generations to accomplish. All along the way meaningful volunteer opportunities will appear. As envisioned, the corridor will wind northward through the In the end, the Barrington area will reap the benefits of weaving Barrington area, from Poplar Creek Forest Preserve south of nature deep into the fabric of our society. I-90 into southeast McHenry County. There are almost 18,000 protected acres in the coalition area. CFC is negotiating a new land purchase we hope to announce shortly which will add to the total. A coalition called the Fox River Hill and Fen Partnership has been created to begin native habitat restoration on a larger scale throughout the Greenway corridor, with a specific focus on wildlife reintroduction, a developing science. Accordingly, the partnership will concentrate on 12 priority species of wildlife identified by Chicago Wilderness as native to our region’s ecosystems. The species include Blanding’s turtle, blue spotted salamander, bobolink, little brown bat, monarch butterfly and red-headed woodpecker. CFC’s support for this project entails monitoring, habitat restoration and actual reintroduction. -

2003 495 Snakes of the United States and Canada

BookReviews117(3).qxd 6/11/04 7:58 PM Page 495 2003 BOOK REVIEWS 495 Snakes of the United States and Canada By Carl H. Ernst and Evelyn M. Ernst. 2003. Smithsonian The maps have surprisingly good detail despite their Books, Washington. xi+668 pages. US$70, CAN$105.00 size which ruled out plotting individual records. The ISBN 1-58834-019-8 subdivisions of ranges into subspecies is not mapped It is over four-and-a-half decades since the publi- but given only in the text. Distributions for the 25 cation of the comprehensive two-volume Handbook of species (three families) which range into Canada are Snakes of United States and Canada by Albert Hazen generally accurate. Exceptions may be the central and Anna Allen Wright (reviewed in The Canadian Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia portions Field-Naturalist 71(4): 201-202 by J. S. Bleakney, for the Western Terrestrial Gartersnake Thamnophis 1957). Those volumes emphasized the need for life elegans (page 385) and the central Alberta and British Thamnophis sirtalis history data and presented the first distribution maps Columbia portions for (page 429) where, following some other recent authors, a disjunct for all species covered (this was a year before the first patchwork is shown. These likely reflect just a lack field guide to amphibians and reptiles in the Peterson of sufficient observations in these areas rather than series appeared). The intervening period has seen not actual range gaps. There is a northernmost disjunct only a proliferation of ecological and behavioural stud- shown for the Northwestern Garter Snake, Thamnophis ies but the compilations of extensive data-bases on dis- ordinoides (page 403), apparently in the vicinity of tribution for virtually every region of North America.