Expressions and Embeddings of Deliberative Democracy in Mutual Benefit Digital Goods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nurturing the Proliferation of Open Source Software

White Paper opensource vision Nurturing the proliferation of Open Source Software 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................................................................ii 1 Introduction.................................................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Challenges and opportunities....................................................................................................................................2 1.2 The wider context ......................................................................................................................................................3 1.3 Potential impact, issues and mitigating them ........................................................................................................4 2 Core strategic principles ........................................................................................................................................................6 3 Current landscape ........ .............................................................................................................................................................7 3.1 Government context..................................................................................................................................................7 3.2 EU context .....................................................................................................................................................................9 -

FOSS:Fostering Knowledge, Development and Communities

f r e e . a n d . o p e n . s o u r c e . community& n . s o u r c e . s o f t w a r e . independentmedia w a r e . f r e e . a n d . o p e n . s FOSS: Fostering a n d . o p e n . s o u r c e . s o Knowledge, e . f r e e . a n d . o p e n . s o f t w a r e . fff r e e . a n d . Development e n . s ooo u r c e . s o f t w a fff r e e . a n d . and Comme . sss ooounities u r c e . s o f t w a by Precy Obja-an n d . ooo p e n . s ooo u r c e . s o f t w a People’s Communications for Development (PC4D) may not have found new information and communications technologies empowering for grassroots women, owing to the practical constraints of equipment cost, intermittent electricity, and specialised skills and the structural constraints posed by the patriarchy project. But new ICTs are here to stay, forming the very backbone of modern communication systems, media production, trade and various services. And for intermediary groups such as women’s organisations, they are among the effective ways of pursuing advocacies and reaching out to more stakeholders. As the study noted, “[PC4D] does not ICTs have been seen as an opportunity signify that new ICTs cannot be useful in forwarding private interest, especially or empowering for grassroots women in the spirit of neoliberalism. -

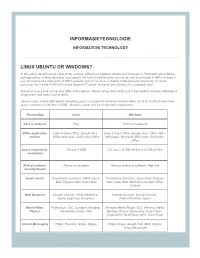

Informasietegnologie Linux Ubuntu Or Windows?

POST LIST INFORMASIETEGNOLOGIE INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY LINUX UBUNTU OR WINDOWS? In this article we will look at a few of the common differences between Ubuntu and windows 8. Firstly with any software package before making decisions most people will look at what it would cost me as user to purchase it. With windows 8 you are looking at a retail price of R800 upwards, but of course as a student of Stellenbosch University, it can be purchased for a mere R180-00 from the Student IT Centre. However with Ubuntu, it’s completely free! Now let’s have a look at how they differ at first glance, Ubuntu brings their Unity look to the platform whereas Windows 8 brings there new metro look to theirs. Ubuntu is also a fairly light weight operating system compared to Windows 8 which takes up 16 to 20 GB of hard drive space compared to Ubuntu’s 4.5GB. Below is a table of a list of relevant comparisons. Feature/App Linux Windows Cost to end-user Free R800 and upwards Office application Libre & Open Office, Google docs, Libre & Open Office, Google docs, Office 365 + choices Office Web Apps, Soft maker Office Web Apps, Microsoft Office suite, Soft maker Office Space required for OS size 4.5GB OS size is 16 GB (32-bit) or 20 GB (64-bit) installation Risk of software Almost non existent Various malicious software, High risk security threats Email clients Thunderbird, Evolution, KMail, Opera Thunderbird, Evolution, Opera Mail, Pegasus Mail, Pegasus Mail, Claws Mail Mail, Claws Mail, Windows Live Mail, Office Outlook Web Browsers Google Chrome, Firefox/Waterfox, -

January 2011 January 2011

Editorial Chris McPhee and Michael Weiss IT Cost Optimization Through Open Source Software Mark VonFange and Dru Lavigne Best Practices in Multi-Vendor Open Source Communities Ian Skerrett How Firms Relate to Open Source Communities Michael Ayukawa, Mohammed Al-Sanabani, and Adefemi Debo-Omidokun Private-Collective Innovation: Let There Be Knowledge Ali Kousari and Chris Henselmans Control in Open Source Software Development Robert Poole Nokia's Hybrid Business Model for Qt John Schreuders, Arthur Low, Kenneth Esprit, and Nerva Joachim Recent Reports Upcoming Events Contribute january 2011 january 2011 Editorial 3 PUBLISHER Chris McPhee and Michael Weiss discuss the editorial theme: The Business of Open Source The Open Source Business Resource is a IT Cost Optimization Through Open Source Software 5 monthly publication of Mark VonFange and Dru Lavigne analyze the use of using free/libre the Talent First Network. open source software as a cost-effective means for the modern Archives are available at: enterprise to streamline its operations. http://www.osbr.ca Best Practices in Multi-Vendor Open Source Communities 11 EDITOR Ian Skerrett describes best practices for companies that wish to lower development costs and gain access to wider addressable markets Chris McPhee through engagement with open source communities. [email protected] How Firms Relate to Open Source Communities 15 ISSN Michael Ayukawa, Mohammed Al-Sanabani, and Adefemi Debo- Omidokun explore the relationship between firms and open source 1913-6102 communities. They illustrate the types of roles and strategies companies can employ to meet their business objectives. ADVISORY BOARD Private-Collective Innovation: Let There Be Knowledge 22 Chris Aniszczyk Ali Kousari and Chris Henselmans describe the benefits and risks of EclipseSource the private-collection innovation model, in which an innovator may Tony Bailetti chose to collaborate with others while still keeping some intellectual Carleton University property private. -

Open Source a Free Software

JIHOČESKÁ UNIVERZITA V ČESKÝCH BUDĚJOVICÍCH PEDAGOGICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra informatiky Open source a free software Mgr. Jiří Pech, Ph.D. České Budějovice 2008 Tato publikace neprošla redakční ani jazykovou úpravou. Grafická úprava: Jiří Pech 2 Obsah 1 Úvod 6 2 Vymezení pojmů 7 2.1 Přehled kategorií software . 7 2.2 Freesoftware(FS) ........................ 9 2.3 OpenSourceSoftware(OSS). 11 2.3.1 VztahGNUaOSS .................... 13 2.4 PříkladyOSSaFSprogramů . 13 3 UNIX se představuje 15 3.1 Historie UNIXu . 15 3.2 Vlastnosti OS UNIX . 17 3.2.1 Systém souborů a adresářový strom . 18 3.2.2 Bezpečnost uživatelů UNIXu . 19 3.3 ZákladnípříkazyUNIXu . 20 3.4 Grafickýrežim........................... 27 3.5 Přehled UNIXů . 28 3.5.1 GNU/Linux ........................ 28 3.5.2 BSD ............................ 28 3.5.3 MINIX........................... 32 3.5.4 IRIX............................ 32 3.5.5 AIX ............................ 32 3.5.6 HP-UX .......................... 33 3.5.7 MacOSX......................... 33 3.5.8 GNU/Hurd ........................ 33 4 Linux – UNIX pro masy 34 4.1 CojeLinux ............................ 34 4.2 HistorieLinuxu .......................... 35 4.2.1 Vývojverzí ........................ 36 4.3 DistribuceLinuxu......................... 37 3 4.4 Slackware ............................. 38 4.5 Red Hat a jeho odvozeniny . 39 4.5.1 SUSELinuxaOpenSUSE . 39 4.5.2 Mandriva ......................... 40 4.5.3 Dalšírpmdistribuce . 40 4.5.4 Ukázkaprácesprogramemrpm . 40 4.6 Debianajehoodvozeniny . 40 4.6.1 Ukázka práce s programem APT . 41 4.6.2 Ubuntuajehoodvozeniny . 41 4.6.3 Jiné distribuce založené na Debianu . 42 4.7 Překládanédistribuce. 42 4.7.1 GentooLinux ....................... 42 4.7.2 Ukázka práce s programem emerge . 42 4.7.3 Jinépřekládanédistribuce . -

Human, Time and Landscape - Blender As a Content Production Tool

Human, Time and Landscape - Blender as a content production tool Juho Vepsäläinen University of Jyväskylä September 27, 2008 Abstract Across time people have affected their surroundings. Relics of the past can be seen in the current world and landscape. Understanding history helps us to understand the present better and preserve our cultural heritage. This project aims to produce a window to the past by using computer generated graphics. Multiple views shall be created each going further into the past. These views are formed as worlds in which the user can study the village on global and local perspectives. A small Finnish village, Toivola, was chosen as the target for this venture. Literature mentioning Toivola exists beginning from the Middle Ages making Toivola an ideal target. An engine capable of rendering the world will be created. It will be based on OpenSceneGraph, a graphics toolkit that is available under open source license. This toolkit has been used for similar projects earlier. Blender, a 3D production tool, and the GIMP, an image manipulation tool, are used for content production. Both tools are based on open source. This paper shows how these tools are used in this project. Also analysis of the current workflow is provided. 1 Introduction Computer graphics is a relatively young field. In 1961 Ivan Sutherland created Sketchpad program which allowed the user to draw using a computer [1]. Since then computer graphics have been used for various different purposes such as games [2], movies (Tron) and of course personal computing. As computing technology has advanced, using computer graphics in massive scale has become more affordable. -

TACCLE1-Libro Sobre E-Learning.Pdf

TACCLE Teachers’ Aids on Creating Content for Learning Environments The E-learning Handbook for Classroom Teachers 2TACCLE handbook TACCLE Teachers’ Aids on Creating Content for Learning Environments The E-learning Handbook for Classroom Teachers Jenny Hughes, Editor Jens Vermeersch, Project coordinator Graham Attwell, Serena Canu, Kylene De Angelis, Koen DePryck, Fabio Giglietto, Silvia Grillitsch, Manuel Jesús Rubia Mateos, Sébastián Lopéz Ojeda, Lorenzo Sommaruga, Narciso Jáimez Toro TACCLE handbook3 TACCLE THE E-LEARNING HANDBOOK FOR CLASSROOM TEACHERS BRUSSELS GO! ONDERWIJS VAN DE VLAAMSE GEMEENSCHAP 2009 IF YOU HAVE ANY QUESTIONS REGARDING THIS BOOK OR THE PROJECT FROM WHICH IT ORIGINATED: VEERLE DE TROYER AND JENS VERMEERSCH HET GO! ONDERWIJS VAN DE VLAAMSE GEMEENSCHAP - INTERNATIONALISATION DEPARTMENT EMILE JACQMAINLAAN 20 • B -1000 BRUSSEL TELEPHONE: +32 02 790 95 98 • E-MAIL: [email protected] JENNY HUGHES [ED.] 132 PP. –29,7 CM. D/2009/8479/001 ISBN 9789078398004 THE EDITING OF THIS BOOK WAS FINISHED ON THE 29TH OF MAY 2009. COVER-DESIGN AND LAYOUT: BART VLIEGEN (WWW.WATCHITPRODUCTIONS.BE) PROJECT WEBSITE: WWW.TACCLE.EU THIS COMENIUS MULTILATERAL PROJECT HAS BEEN FUNDED WITH SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION PROJECT NUMBER: 133863-LLP-1-2007-1-BE-COMENIUS-CMP. THIS BOOK REFLECTS THE VIEWS ONLY OF THE AUTHORS, AND THE COMMISSION CANNOT BE HELD RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY USE THAT MAY BE MADE OF THE INFORMATION CONTAINED THEREIN. PROJECT COORDINATION: JENS VERMEERSCH WITH THE HELP OF VEERLE DE TROYER AND HANNELORE AUDENAERT TACCLE BY JENNY HUGHES, GRAHAM ATTWELL, SERENA CANU, KYLENE DE ANGELIS, KOEN DEPRYCK, FABIO GIGLIETTO, SILVIA GRILLITSCH, MANUEL JESÚS RUBIA MATEOS, SÉBASTIÁN LOPÉZ OJEDA, LORENZO SOMMARUGA, NARCISO JÁIMEZ TORO, JENS VERMEERSCH IS LICENSED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION-NON-COMMERCIAL-SHARE ALIKE 2.0 BELGIUM LICENSE. -

Role of FOSS in Development of Libraries and Information Centers

International Journal of Library Information Network and Knowledge Volume 3 Issue 2, 2018, ISSN: 2455-5207 Grabbing the feast free: Role of FOSS in development of Libraries and Information centers “World is Open Source!” Anonymous Priya Rai Deputy Librarian National Law University Delhi [email protected] Abstract Open Source Software is a worldwide movement which is supported not only by individual government but international organization viz. World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) which also underlines its importance in intellectual property regime. The paper is an attempt to trace benefits of open source movement, basic understanding of free and open source software, legal issues associated with it and integration of open software with library management. The paper highlights open source software policy of India as introduced by Ministry of Information Technology in 2015. Also lists a number of open source software useful for various activities viz. automation, digital library management, website management and other routine activities in the Libraries. Keywords: Open source software, Integrated library management software, Open source software policy 1 Introduction In this technological transformation age libraries are enjoying the dynamics of collaborations and developments in software industries. The digital India project initiated by the Prime Minister of India with the objectives and vision of integrated of knowledge strength and providing access platform with no barriers. The Prime Minister urged the technology industries to create a platform for wider use and radical impact in the country without any accessing hindrance. The open source community introduced many new sets of software packages for the integration of library systems. Many libraries are migrating from proprietary integrated library software to open source software. -

LATEX and Beamer: Open Source Alternatives to Microsoft Office for Documents and Presentations —Or— Why Keep Payin’ ’Da Man When You Can Do Better?

LATEX and Beamer: Open Source Alternatives to Microsoft Office For Documents and Presentations —or— Why Keep Payin’ ’da Man When You Can Do Better? Mark R. Galvin K Nelson Department of Nuclear Engineering and Radiation Health Physics Oregon State University 13 November 2008 Mark R. Galvin/K Nelson LATEX and Beamer What’s This All About? Objective is to answer the following questions: What is Free/Open Source Software? What the heck are TEX and LATEX? Who uses LATEX? Why would I use LATEX? Why wouldn’t I use LATEX? How do I get LATEX? How do I use LATEX? A Note on Beamer: Beamer is one of several available presentation making packages that use the LATEX markup format and the TEX engine to produce beautiful presentations (like this one) in PDF format. Beamer won’t explicitly be discussed. Mark R. Galvin/K Nelson LATEX and Beamer Free/Open Source Software . think free speech, not free beer What is F/OSS? Free/open source software (F/OSS) is software for which the human-readable source code is made available to the user of the software, who can then modify the code in order to fit the software to the user’s needs. The source code is the set of written instructions that define a program in its original form, and when it’s made fully accessible programmers can read it, modify it, and redistribute it, thereby improving and adapting the software. In this manner the software evolves at a rate unmatched by traditional proprietary software. Where is it? Hiding on the internet. -

OPEN SOURCE SOFTWARE WHAT’S INSIDE What Is Open Source This Booklet Will Be Useful for Small Businesses That Would Like Software (OSS)?

OPEN SOURCE SOFTWARE WHAT’S INSIDE What is Open Source This booklet will be useful for small businesses that would like Software (OSS)? ..................................1 to learn more about open source software, its benefits and Is it free? .............................................2 limitations. The booklet also contains a reference list of some How is Open Source Software of the most commonly used open source software. Useful to Small Businesses? ..............3 Is There a Downside to Using Open Source Software? ............4 What is Open Source Software (OSS)? How Do I Know if a Particular OSS Application Is Right for Open source software is computer software that has a source code My Business? ......................................8 available to the general public for use as is or with modifications. This Support Services for OSS ....................9 software typically does not require a license fee. OSS vs. Freeware vs. Shareware ......10 OSS has become very popular and there are OSS applications for a Pitfalls to Using Freeware variety of different uses such as office automation, web design, content and Shareware ..................................10 management, operating systems, and communications. Some of the most popular software packages such as Mozilla Firefox, the Linux Operating Future Trends ....................................11 System and Apache web server software, are examples of OSS. Related Topics Covered in Other Booklets ..............................11 The key difference between OSS and proprietary software is its license. As copyright material, software is almost always licensed. The license indicates how the software may be used. OSS is unique in that it is always released under a license that has been certified to meet the criteria of the Open Source Definition. -

Tabla De Aplicaciones Equivalentes Windows / GNU Linux Orientada Al Usuario En General O Promedio

Tabla de aplicaciones equivalentes Windows / GNU Linux Orientada al usuario en general o promedio. Imágen Nomacs http://www.nomacs.org/ Viewnior http://siyanpanayotov.com/project/viewnior/ Visor de imágnes Eye of GNOME (http://www.gnome.org/projects/eog/) ACDSee etc. Gwenview (http://gwenview.sourceforge.net/) XnView http://www.xnview.com/ digiKam (http://www.digikam.org/) Albums de fotos F-Spot (http://f-spot.org/Main_Page) Picasa, CyberLink gThumb (http://live.gnome.org/gthumb/) PhotoDirector, etc Shotwell (http://www.yorba.org/shotwell/) Editor de metadatos de FotoTagger (http://sourceforge.net/projects/fototagger/) imágnes ExifTool http://www.sno.phy.queensu.ca/~phil/exiftool/ PhotoME Inkscape (http://www.inkscape.org/) Skencil (http://www.skencil.org/) Editor de gráficos vectoriales SK1 http://sk1project.org/ Adobe Illustrator Xara Xtreme (http://www.xaraxtreme.org/) Corel Draw Alchemy (http://al.chemy.org/gallery/) Libre Office Draw (https://es.libreoffice.org/descubre/draw/) Blender (http://www.blender.org/) Natron https://natron.fr/ Gráficos 3D K-3D (http://www.k-3d.org/) 3D Studio Max Wings 3D http://www.wings3d.com/ After Effects Art of Illusion (http://www.artofillusion.org/) Jahshaka http://www.jahshaka.com/ KolourPaint (http://kolourpaint.sourceforge.net/) Pintura digital Pinta (http://pinta-project.com/) MS Paint TuxPaint (http://tuxpaint.org/) Pintura digital profesional Kitra (https://krita.org/) Corel PaintShopPro Pencil (http://www.pencil-animation.org/) -

Open Source Applications for Education

Open Source Applications for Education With shrinking budgets, open source & freeware applications are worth exploring. Take a look at the best applications for your computers: from painting to publishing. Back End – Server based Apache, Bind, MySQL, Moodle, Drupal, SquidGuard, Dans Guard, Sendmail, Squid, OpenLDAP, IPCop Front End - Operating system Educational versions of Linux www.edubuntu.org http://www.linuxinsider.com/rsstory/56656.html www.netc.org/openoptions Front End – Applications used online Online applications a growing and viable alternative if you have the bandwidth. Some of the most popular will be highlighted at my next presentation: Web 2.0 - Free Learning Tools. Front End – Applications used locally Open Source and Free applications we’ll explore. Most are Windows specific though with Linux versions of many of these programs or Mac OX running Parallels – this is becoming less of an issue. There are also some excellent applications which have been created only for Mac OS which we will not review. • TuxPaint and TuxPaint Config • PowerToy Calculator (graphing) • OpenOffice/StarOffice • Picasa 2 • PhotoFiltre • PhotoStory 3 • GIMP/GIMPshop • Audacity • West Point Bridge Designer • MovieMaker 2 • Hector Protector • Google SketchUp • K9Web Protection • VCW Vicman's Photo Editor • Sqirlz Morph • IrfanView and FastStone • Magnifier Powertoy • NvU Andy Mann Page 1 Instructional Technologist [email protected] Open Source & Free Desktop Applications Presentation format 1. Share and learn from each other – you may have a program to share or positive or negative experience with one of these applications. Please share. 2. Overview of applications, some open sources and others freeware. 3. We’ll review desktop open source applications not server open source applications.