Ownership Concentration and Indecency: Is There a Link? Jonathan Rintels Fordham University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

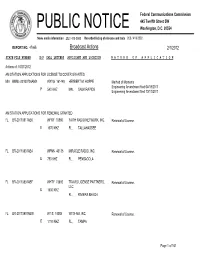

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BTCCT-20061212AVR Communications, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CCF, et al. (Transferors) ) BTCH-20061212BYE, et al. and ) BTCH-20061212BZT, et al. Shareholders of Thomas H. Lee ) BTC-20061212BXW, et al. Equity Fund VI, L.P., ) BTCTVL-20061212CDD Bain Capital (CC) IX, L.P., ) BTCH-20061212AET, et al. and BT Triple Crown Capital ) BTC-20061212BNM, et al. Holdings III, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CDE, et al. (Transferees) ) BTCCT-20061212CEI, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212CEO For Consent to Transfers of Control of ) BTCH-20061212AVS, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212BFW, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting – Fresno, LLC ) BTC-20061212CEP, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting Operations, LLC; ) BTCH-20061212CFF, et al. AMFM Broadcasting Licenses, LLC; ) BTCH-20070619AKF AMFM Radio Licenses, LLC; ) AMFM Texas Licenses Limited Partnership; ) Bel Meade Broadcasting Company, Inc. ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; ) CC Licenses, LLC; CCB Texas Licenses, L.P.; ) Central NY News, Inc.; Citicasters Co.; ) Citicasters Licenses, L.P.; Clear Channel ) Broadcasting Licenses, Inc.; ) Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; and Jacor ) Broadcasting of Colorado, Inc. ) ) and ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BAL-20070619ABU, et al. Communications, Inc. (Assignors) ) BALH-20070619AKA, et al. and ) BALH-20070619AEY, et al. Aloha Station Trust, LLC, as Trustee ) BAL-20070619AHH, et al. (Assignee) ) BALH-20070619ACB, et al. ) BALH-20070619AIT, et al. For Consent to Assignment of Licenses of ) BALH-20070627ACN ) BALH-20070627ACO, et al. Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; ) BAL-20070906ADP CC Licenses, LLC; AMFM Radio ) BALH-20070906ADQ Licenses, LLC; Citicasters Licenses, LP; ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; and ) Clear Channel Broadcasting Licenses, Inc. ) Federal Communications Commission ERRATUM Released: January 30, 2008 By the Media Bureau: On January 24, 2008, the Commission released a Memorandum Opinion and Order(MO&O),FCC 08-3, in the above-captioned proceeding. -

SPONSORSHIP / PROGRAM PARTNERSHIP Sunday, March 25, 2018 (11AM—5PM) EVENT OVERVIEW

Friday, March 23, 2018 (4PM—10PM) Saturday, March 24, 2018 (11AM—10PM) SPONSORSHIP / PROGRAM PARTNERSHIP Sunday, March 25, 2018 (11AM—5PM) EVENT OVERVIEW Wellington Bacon & Bourbon Fest! WHERE At the crossroads of American culture where Village of Wellington Community Center & Bourbon Street and Bacon Street meet, the Village Amphitheater of Wellington and Delray Beach Arts, Inc. brings you 1200 Forest Hill Blvd. the 3rd Annual Bacon & Bourbon Fest scheduled for Wellington, FL 33414 March 24-26, 2017. WHEN March 24—26, 2017 At the heart of our festival is our commitment to create fun filled food lover community events ATTENDANCE featuring unique foods and beverages. We strive to Anticipated attendance 30,000 over 3 days ensure that our sponsors are richly rewarded for their investment in our events and our community. ADMISSION FREE FESTIVAL FEATURES The three-day event will offer FREE ADMISSION and is CONTACT held on the grounds surrounding the Village of Wel- Nancy Stewart-Franczak, CFEE Executive Director lington Community Center and amphitheater, fea- [email protected] turing live musical entertainment, artist & crafters, an 561-274-4663 eclectic menu of bacon infused culinary delights and a collection of over 40 bourbons and whiskeys Sarah Vallely, CFEE for your tasting pleasure. The Fest also offers partici- Assistant Executive Director pants exclusive bacon and bourbon pairing seminars [email protected] 561-279-0907 including exclusive Pappy Van Winkle tastings. South Florida’s foremost Bourbon experts share the distiller’s John Franczak art and patient techniques in the seminars and tast- Sponsorship Sales Manager ings. All intended to enhance your knowledge and [email protected] pleasure of American made Bourbon and whiskey. -

KOSF Don Bleu & Carolyn

Holiday 2014 Campaign Recap Contents Overview Assets Live & Produced Spots Social Experiential Digital Results Contacts Campaign Overview Objective Drive retail sales of coffee and tea holiday gifts, blends, seasonal drinks in the San Francisco Bay Area and Washington D.C. metro during this pivotal and record short retail season. Strategy iHeartMedia will leverage organic DJ chatter promoting the brand and area locations with top on-air personalities, social networks and experiential marketing in high traffic locations. Net Investment Combined markets: $180,000 Campaign Overview ENDORSEMENT Commercial Messaging ● 11/10-11/17 MUSIC ● 12/01-12/22 ● 11/10-11/17 Peet’s Sampling ● San Francisco and :30 ● 12/01-12/22 ● onsites Washington D.C. ● Schedule weighted ● key retail areas around key shopping ● supported on- :15 dates line and on-air Social ● All talent support the campaign with social features NOV DEC Holiday Shopping Season BLACKBLACK FRIDAY 1 3 Only 3 Power Weekends between 60% One of just 26 days, Black 2 Thanksgiving and Christmas Friday, is a key Of Holiday to drive sales for the year purchase are revenue day in the shortest shopping Made Thanksgiving weekend season possible Campaign: San Francisco Talent Sana G & Miss Kimmie KMEL-FM Renel & Christie AM Drive KISQ-FM Rhythmic CHR AM Drive Rhythmic AC Sandy & Marcus D. Don Bleu & Carolyn KIOI-FM KOSF-FM AM Drive AM Drive Adult Contemporary Classic Hits Armstrong & Getty JV & Selena KKSF-AM KYLD-FM AM Drive AM Drive News Talk Pop CHR Campaign: Washington D.C. Talent Aly Jacobs Loo Katz WMZQ-FM WASH-FM AM Drive AM Drive Country Adult Contemporary Lisa Berigan WBIG-FM Afternoons Classic Hits Intern John WIHT-FM AM Drive Contemporary. -

A Strategic Guide for the City-Wide Response to and Recovery from Major Emergencies and Disasters

OFFICE of EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT - BASIC PLAN Albuquerque, New Mexico A STRATEGIC GUIDE FOR THE CITY-WIDE RESPONSE TO AND RECOVERY FROM MAJOR EMERGENCIES AND DISASTERS Martin J. Chávez, Mayor CITY OF ALBUQUERQUE ALL HAZARDS EMERGENCY OPERATIONS PLAN VOLUME 2 - ANNEXES DECEMBER 2005 PREPARED BY: THE CITY OF ALBUQUERQUE OFFICE OF EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT OFFICE of EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT - BASIC PLAN ALBUQUERQUE EMERGENCY OPERATIONS PLAN VOLUME 2 - ANNEXES Table of Contents Annex # Page Annex 1 Direction and Control A-1-1 thru A-1-12 Annex 2 Communications, Warning & Emergency Alert A-2-1 thru A-2-15 Annex 3 Alert & Notification A-3-1 thru A-3-6 Annex 4 Law Enforcement A-4-1 thru A-4-24 Annex 5 Fire and Rescue A-5-1 thru A-5-22 Annex 6 Health and Medical A-6-1 thru A-6-55 Annex 7 Critical Infrastructure A-7-1 thru A-7-11 Annex 8 Damage Assessment and Reporting A-8-1 thru A-8-13 Annex 9 Transportation A-9-1 thru A-9-6 Annex 10 Evacuation A-10-1 thru A-10-20 Annex 11 Logistics and Resources A-11-1 thru A-11-3 Annex 12 Education, Training, Testing and Exercises A-12-1 thru A-12-11 ALBUQUERQUE EMERGENCY OPERATIONS PLAN ANNEX 1 DIRECTION & CONTROL Primary Responsibility: Mayor of the City of Albuquerque/President of the City Council Chief Administrative Officer Chief Public Safety Officer Secondary Responsibility: All City Departments and Divisions Lead Agencies Emergency Management Fire Police Environmental Health Secondary Agencies Water Authority Municipal Development Legal Finance & Administrative Services Solid Waste Management Transit Senior Affairs Family & Community Services I. -

Agenda Regular Meeting City of Fairfield Planning Commission

AGENDA REGULAR MEETING CITY OF FAIRFIELD PLANNING COMMISSION VIA TELECONFERENCE FEBRUARY 10, 2021 JOIN MEETING VIA ZOOM LINK: 6:00 P.M. https://fairfieldca.zoom.us/j/97065607498?pwd=a1dnaVY2UzFINU4xaU5sS0FET09qZz09 PASSWORD: 66781819 Consistent with the Governor's Executive Order N-29-20 regarding public meetings during the COVID-19 emergency, Planning Commissioners may attend the meeting telephonically. Members of the public can observe the meeting on Comcast Cable Channel 26, ATT U-Verse 99, and web-streamed live http://www.fairfield.ca.gov/live, or at www.youtube.com/user/FFCATV/live. Members of the public may join the meeting via Zoom with the following link: https://fairfieldca.zoom.us/j/97065607498?pwd=a1dnaVY2UzFINU4xaU5sS0FET09qZz09 Password: 66781819 I. ROLL CALL II. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE III. INFORMATION ON PROVIDING PUBLIC COMMENTS Persons wishing to address the Planning Commission on subjects not on the agenda but within the jurisdiction of the Planning Commission provided that NO action may be taken on off-agenda items except as authorized by law. Off-agenda items from the public will be taken under consideration without discussion by the Commission and may be referred to staff. Comments will be accepted via Zoom or by email at [email protected]. Identify your name, the item you wish to comment on, and the date of the meeting. All comments received by email prior to the start of an item will be read aloud for up to three minutes. For adjudicative public hearing items, e-mailed comments will be accepted and read aloud for up to three/four minutes if received prior to the close of the public hearing PUBLIC COMMENT INSTRUCTIONS: When joining via Zoom, please use the “raise your hand” feature or press *9 on your phone to request to speak. -

Joa 1 9 8 1 0 0 0 0 . 0 2 6 . 0 0 9 . 2 7

SOLIDARITY SOLIDARITY official organ of the Black Consciousness Movement of Azania No. 7 Third Quarter 1981 0 Marxism by Walter in Africa Rodney * Steve Biko Memorial Address * International of Crime and Terror Invades Angola PRICE 50p OUR BANNING IS NO CAUSE FOR CELEBRATION ..~ ing SoiktIiv. No. 5. fis 1mww 19W i illsih Cwoua Momeol AImW umemie Vn Oktcmram of Pubictkw km dm - mamt dIdomVabeumt@i of Vspmabcw,, -Se Rm Daily Mai 23.6J1. kew ovrseas -d . have m wam usipm fo SOLIDARITY. Tw -ws~ of SOLIDARISTY yw som we u on mef ~tm - But 10 irn s bviw of SOLIDARITY to boos ow sl wouid be dmwqm Ow1 1-r~d n Mfro#ANS10aam SOLIDARITY. is4 a " workb papbids b ~j Afrkm. Tto psk" vwih sdm*SOLI DAR. rTY Is umhmq fr too tow of *sa its beeming ud sot wmdw fm no a- wassm m o help SOLIDARITY autoa #a bem"~ oedin merw and la fai Morn pi in Souw* Aftwo .m it W~ most EWM. fte out mn wm *~Awpbon: )r,lotuskImomiamVaOWnYo.bWIna - upora un subcar -fi a t £ 1.00 S -pn- 11 by t il codw v SOLIDARITY ACCUNT NO. 007W16. Lloyds B"i Ltd.. STow~m Comet Raw., LMb WIP 0(0. SOLIDARITY PAWS, ttvoi'Wt c and difwwon loumel of dw 81mck Coiouu~ MObwrang of Azana CONTENTS Thrd Omt .19 1. No 7 THE INTIERKAT1ONAL OF CRUE AND TERROR INEVADES ANGOLA Pap 3 STEVE UKO WEMIORIAL ADORESS Paso 6 In the Polltxca dolk'wyv Of the ,uxt. Wma* umwiurty studsets mrd~e for ways to reww* thw MOpCY G4 bwviad Itertmon numirnts. -

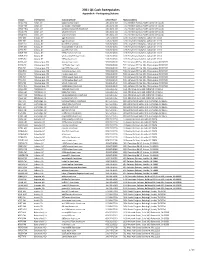

2021 Q1 Cash Sweepstakes Appendix a - Participating Stations

2021 Q1 Cash Sweepstakes Appendix A - Participating Stations Station iHM Market Station Website Office Phone Mailing Address WHLO-AM Akron, OH 640whlo.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WHOF-FM Akron, OH sunny1017.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WHOF-HD2 Akron, OH cantonsnewcountry.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WKDD-FM Akron, OH wkdd.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WRQK-FM Akron, OH wrqk.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WGY-AM Albany, NY wgy.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WGY-FM Albany, NY wgy.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WKKF-FM Albany, NY kiss1023.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WOFX-AM Albany, NY foxsports980.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WPYX-FM Albany, NY pyx106.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WRVE-FM Albany, NY 995theriver.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WRVE-HD2 Albany, NY wildcountry999.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WTRY-FM Albany, NY 983try.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 KABQ-AM Albuquerque, NM abqtalk.iheart.com 505-830-6400 5411 Jefferson NE, Ste 100, Albuquerque, NM 87109 KABQ-FM Albuquerque, NM 1047kabq.iheart.com 505-830-6400 5411 Jefferson NE, Ste 100, Albuquerque, NM -

When Being No. 1 Is Not Enough

A Report Prepared by the Civil Rights Forum on Communications Policy When Being No. 1 Is Not Enough: The Impact of Advertising Practices On Minority- Owned & Minority-Formatted Broadcast Stations Kofi Asiedu Ofori Principal Investigator submitted to the Office of Communications Business Opportunities Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. All Rights Reserved to the Civil Rights Forum on Communications Policy a project of the Tides Center Synopsis As part of its mandate to identify and eliminate market entry barriers for small businesses under Section 257 of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, the Federal Communications Commission chartered this study to investigate practices in the advertising industry that pose potential barriers to competition in the broadcast marketplace. The study focuses on practices called "no Urban/Spanish dictates" (i.e. the practice of not advertising on stations that target programming to ethnic/racial minorities) and "minority discounts" (i.e. the practice of paying minority- formatted radio stations less than what is paid to general market stations with comparable audience size). The study consists of a qualitative and a quantitative analysis of these practices. Based upon comparisons of nationwide data, the study indicates that stations that target programming to minority listeners are unable to earn as much revenue per listener as stations that air general market programming. The quantitative analysis also suggests that minority-owned radio stations earn less revenues per listener than majority broadcasters that own a comparable number of stations nationwide. These disparities in advertising performance may be attributed to a variety of factors including economic efficiencies derived from common ownership, assessments of listener income and spending patterns, or ethnic/racial stereotypes that influence the media buying process. -

Progress Report Forest Service Grant / Agrreement No

PROGRESS REPORT FOREST SERVICE GRANT / AGRREEMENT NO. 13-DG-11132540-413 Period covered by this report: 04/01/2014—05/31/2015 Issued to: Center of Southwest Culture, Inc. Address: 505 Marquette Avenue, NW, Suite 1610 Project Name: Arboles Comunitarios Contact Person/Principal Investigator Name: Arturo Sandoval Phone Number: 505.247.2729 Fax Number: 505.243-1257 E-Mail Address: [email protected] Web Site Address (if applicable): www.arbolescomunitarios.com Date of Award: 03/27/2013 Grant Modifications: Date of Expiration: 05/31/2015 Funding: Federal Share: $95,000 plus Grantee Share: $300,000 = Total Project: $395,000 Budget Sheet: FS Grant Manager: Nancy Stremple / Address: 1400 Independence Ave SW, Yates building (3 Central) Washington, DC 20250-1151 Phone Number: 202/309-9873 Albuquerque Service Center (ASC) Send a copy to: Albuquerque Service Center Payments – Grants & Agreements 101B Sun Ave NE Albuquerque, NM 87109 EMAIL: [email protected] FAX: 877-687-4894 Project abstract (as defined by initial proposal and contract): Arboles Comunitarios is proposed under Innovation Grant Category 1 as a national Spanish language education program. By utilizing the expertise of the Center of Southwest Culture community and urban forestry partners along with the targeted outreach capacity of Hispanic Communications Network, this project will communicate the connection between the personal benefits of urban forest and quality of life in a manner that resonates specifically with the Hispanic community. Project objectives: • Bilingual website with -

The Clear Picture on Clear Channel Communications, Inc.: a Corporate Profile

Cornell University ILR School DigitalCommons@ILR Articles and Chapters ILR Collection 1-28-2004 The Clear Picture on Clear Channel Communications, Inc.: A Corporate Profile Maria C. Figueroa Cornell University, [email protected] Damone Richardson Cornell University, [email protected] Pam Whitefield Cornell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/articles Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, Arts Management Commons, and the Unions Commons Thank you for downloading an article from DigitalCommons@ILR. Support this valuable resource today! This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the ILR Collection at DigitalCommons@ILR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles and Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@ILR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. If you have a disability and are having trouble accessing information on this website or need materials in an alternate format, contact [email protected] for assistance. The Clear Picture on Clear Channel Communications, Inc.: A Corporate Profile Abstract [Excerpt] This research was commissioned by the American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) with the expressed purpose of assisting the organization and its affiliate unions – which represent some 500,000 media and related workers – in understanding, more fully, the changes taking place in the arts and entertainment industry. Specifically, this report examines the impact that Clear Channel Communications, with its dominant positions in radio, live entertainment and outdoor advertising, has had on the industry in general, and workers in particular. Keywords AFL-CIO, media, worker, arts, entertainment industry, advertising, organization, union, marketplace, deregulation, federal regulators Disciplines Advertising and Promotion Management | Arts Management | Unions Comments Suggested Citation Figueroa, M. -

Pynchon's Sound of Music

Pynchon’s Sound of Music Christian Hänggi Pynchon’s Sound of Music DIAPHANES PUBLISHED WITH SUPPORT BY THE SWISS NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION 1ST EDITION ISBN 978-3-0358-0233-7 10.4472/9783035802337 DIESES WERK IST LIZENZIERT UNTER EINER CREATIVE COMMONS NAMENSNENNUNG 3.0 SCHWEIZ LIZENZ. LAYOUT AND PREPRESS: 2EDIT, ZURICH WWW.DIAPHANES.NET Contents Preface 7 Introduction 9 1 The Job of Sorting It All Out 17 A Brief Biography in Music 17 An Inventory of Pynchon’s Musical Techniques and Strategies 26 Pynchon on Record, Vol. 4 51 2 Lessons in Organology 53 The Harmonica 56 The Kazoo 79 The Saxophone 93 3 The Sounds of Societies to Come 121 The Age of Representation 127 The Age of Repetition 149 The Age of Composition 165 4 Analyzing the Pynchon Playlist 183 Conclusion 227 Appendix 231 Index of Musical Instruments 233 The Pynchon Playlist 239 Bibliography 289 Index of Musicians 309 Acknowledgments 315 Preface When I first read Gravity’s Rainbow, back in the days before I started to study literature more systematically, I noticed the nov- el’s many references to saxophones. Having played the instru- ment for, then, almost two decades, I thought that a novelist would not, could not, feature specialty instruments such as the C-melody sax if he did not play the horn himself. Once the saxophone had caught my attention, I noticed all sorts of uncommon references that seemed to confirm my hunch that Thomas Pynchon himself played the instrument: McClintic Sphere’s 4½ reed, the contra- bass sax of Against the Day, Gravity’s Rainbow’s Charlie Parker passage. -

Broadcast Actions 2/1/2012

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 47665 Broadcast Actions 2/1/2012 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 01/27/2012 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR LICENSE TO COVER GRANTED MN BMML-20100726AMX WXYG 161448 HERBERT M. HOPPE Method of Moments Engineering Amendment filed 04/19/2011 P 540 KHZ MN , SAUK RAPIDS Engineering Amendment filed 10/17/2011 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL GRANTED FL BR-20110817ABK WFRF 70860 FAITH RADIO NETWORK, INC. Renewal of License. E 1070 KHZ FL , TALLAHASSEE FL BR-20110831ABA WPNN 43135 MIRACLE RADIO, INC. Renewal of License. E 790 KHZ FL , PENSACOLA FL BR-20110831ABF WHTY 73892 TRAVIS LICENSE PARTNERS, Renewal of License. LLC E 1600 KHZ FL , RIVIERA BEACH FL BR-20110901ABW WTIS 74088 WTIS-AM, INC. Renewal of License. E 1110 KHZ FL , TAMPA Page 1 of 161 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 47665 Broadcast Actions 2/1/2012 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 01/27/2012 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR RENEWAL GRANTED FL BR-20110906AFA WEBY 64 SPINNAKER LICENSE Renewal of License.