How Ex Parte Seizure of Non-Interfering LPFM Does Not Further the FCC's "Public Interest", 43 San Diego L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

U. S. Radio Stations As of June 30, 1922 the Following List of U. S. Radio

U. S. Radio Stations as of June 30, 1922 The following list of U. S. radio stations was taken from the official Department of Commerce publication of June, 1922. Stations generally operated on 360 meters (833 kHz) at this time. Thanks to Barry Mishkind for supplying the original document. Call City State Licensee KDKA East Pittsburgh PA Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Co. KDN San Francisco CA Leo J. Meyberg Co. KDPT San Diego CA Southern Electrical Co. KDYL Salt Lake City UT Telegram Publishing Co. KDYM San Diego CA Savoy Theater KDYN Redwood City CA Great Western Radio Corp. KDYO San Diego CA Carlson & Simpson KDYQ Portland OR Oregon Institute of Technology KDYR Pasadena CA Pasadena Star-News Publishing Co. KDYS Great Falls MT The Tribune KDYU Klamath Falls OR Herald Publishing Co. KDYV Salt Lake City UT Cope & Cornwell Co. KDYW Phoenix AZ Smith Hughes & Co. KDYX Honolulu HI Star Bulletin KDYY Denver CO Rocky Mountain Radio Corp. KDZA Tucson AZ Arizona Daily Star KDZB Bakersfield CA Frank E. Siefert KDZD Los Angeles CA W. R. Mitchell KDZE Seattle WA The Rhodes Co. KDZF Los Angeles CA Automobile Club of Southern California KDZG San Francisco CA Cyrus Peirce & Co. KDZH Fresno CA Fresno Evening Herald KDZI Wenatchee WA Electric Supply Co. KDZJ Eugene OR Excelsior Radio Co. KDZK Reno NV Nevada Machinery & Electric Co. KDZL Ogden UT Rocky Mountain Radio Corp. KDZM Centralia WA E. A. Hollingworth KDZP Los Angeles CA Newbery Electric Corp. KDZQ Denver CO Motor Generator Co. KDZR Bellingham WA Bellingham Publishing Co. KDZW San Francisco CA Claude W. -

The Southern California Radio Reference Guide 4/29/2020

The Southern California Radio Reference Guide 4/29/2020 Call letters Branding Dial position Ownership Nielsen Market Format Phone Website KATY 101.3fm The Mix 101.3 FM All Pro Broadcasting Riverside/San Bernardino Adult Contemporary (951) 506-1222 http://www.1013themix.com/ KHTI Hot 103.9 103.9 FM All Pro Broadcasting Riverside/San Bernardino Hot AC (909) 890-5904 http://www.x1039.com/ KKBB Groove 99-3 99.3 FM Alpha Media USA Bakersfield Rhythmic Oldies (661) 393-1900 https://www.groove993.com/ KLLY Energy 95.3 95.3 FM Alpha Media USA Bakersfield Hot AC (661) 393-1900 https://www.energy953.com/ KNZR 1560 & 97.7 FM KNZR 1560 AM Alpha Media USA Bakersfield News Talk (661) 393-1900 https://www.knzr.com/ KCLB 93.7 KCLB 93.7 FM Alphamedia Palm Springs Rock (760) 322-7890 https://www.937kclb.com/ KDES 98.5 The Bull 98.5 FM Alphamedia Palm Springs Country (760) 322-7891 https://www.985thebull.com/ KDGL The Eagle 106.9 106.9 FM Alphamedia Palm Springs Classic Rock (760) 322-7890 https://www.theeagle1069.com/ U-92.7 The Desert's KKUU 92.7 FM Alphamedia Palm Springs Dance CHR (760) 322-7890 https://www.u927.com/ Hottest Music KNWH / KNWQ / KNWZ K-News, The Voice of 1250 AM/1140 AM/970 Alphamedia Palm Springs Talk (760) 322-7890 https://www.knewsradio.com/ AM & FM The Valley AM/94.3 FM Mix 100.5 The Desert's KPSI FM 100.5 Alphamedia Palm Springs Hot AC (760) 322-7890 https://www.mix1005.fm/ Best Mix KCAL 96.7 K-CAL Rocks 96.7 FM Anaheim Broadcasting Corporation Riverside/San Bernardino Rock (909) 793-3554 https://www.kcalfm.com/ KOLA KOLA 99.9 99.9 FM Anaheim Broadcasting Corporation Riverside/San Bernardino Oldies (909) 793-3554 https://www.kolafm.com/ KCWR Real Country 107.1 FM Buck Owens Broadcasting Bakersfield Country (661) 326-1011 N/A KRJK 97.3 The Bull 97.3 FM Buck Owens Broadcasting Bakersfield Adult HIts (661) 326-1011 https://www.bull973.com/ KUZZ AM/FM (simulcast) KUZZ AM 55 ▪ FM 107.9 550 AM/107.9 FM Buck Owens Broadcasting Bakersfield Country (661) 326-1011 http://www.kuzzradio.com/ KWVE FM K-Wave 107.9 FM Calvary Chapel Church, Inc. -

2021 Iheartradio Music Festival Win Before You Can Buy Flyaway Sweepstakes Appendix a - Participating Stations

2021 iHeartRadio Music Festival Win Before You Can Buy Flyaway Sweepstakes Appendix A - Participating Stations Station Market Station Website Office Phone Mailing Address WHLO-AM Akron, OH 640whlo.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WHOF-FM Akron, OH sunny1017.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WHOF-HD2 Akron, OH cantonsnewcountry.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WKDD-FM Akron, OH wkdd.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WRQK-FM Akron, OH wrqk.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WGY-AM Albany, NY wgy.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WGY-FM Albany, NY wgy.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WKKF-FM Albany, NY kiss1023.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WOFX-AM Albany, NY foxsports980.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WPYX-FM Albany, NY pyx106.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WRVE-FM Albany, NY 995theriver.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WRVE-HD2 Albany, NY wildcountry999.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WTRY-FM Albany, NY 983try.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 KABQ-AM Albuquerque, NM abqtalk.iheart.com 505-830-6400 5411 Jefferson NE, Ste 100, Albuquerque, NM 87109 KABQ-FM Albuquerque, NM hotabq.iheart.com 505-830-6400 -

National Association of Broadcasters” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 5, folder “6/18/75 - National Association of Broadcasters” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. WASHINGTON TO: Sheila Weidenfeld FROM: Margita E. White Assistant Press Secretary to the President It would be great if Mrs. Ford could join the President in greeting the NAB board members and their wives • . .---- Lv Digitized from Box 5 of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library .... .. THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON June 17, 1975 RECEPTION FOR NAB BOARD 'W"ednesday, June 18, 1975 5:00 p. m. (45 minutes} The State Dinirg Room From: Margita E. 'W"hite I. PURPOSE To give the board of directors and officers of the National Association of Broadcasters an opportunity to meet informally with the President during their meeting in 'W"ashington, D. C. II. BACKGROUND, PARTICIPANTS AND PRESS PLAN A. Background The NAB board is meeting in 'W"ashington June 16-20 to elect its top officers from among the board and to discuss issues of concern to broadcasters. -

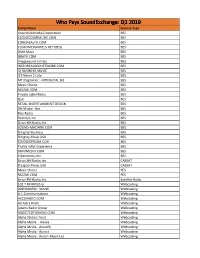

Licensee Count Q1 2019.Xlsx

Who Pays SoundExchange: Q1 2019 Entity Name License Type Aura Multimedia Corporation BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX Music BES GRAYV.COM BES Imagesound Limited BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IO BUSINESS MUSIC BES It'S Never 2 Late BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES Music Choice BES MUZAK.COM BES Private Label Radio BES Qsic BES RETAIL ENTERTAINMENT DESIGN BES Rfc Media - Bes BES Rise Radio BES Rockbot, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES Thales Inflyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES Vibenomics, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT Music Choice PES MUZAK.COM PES Sirius XM Radio, Inc Satellite Radio 102.7 FM KPGZ-lp Webcasting 999HANKFM - WANK Webcasting A-1 Communications Webcasting ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting Ad Astra Radio Webcasting Adams Radio Group Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting Aloha Station Trust Webcasting Alpha Media - Alaska Webcasting Alpha Media - Amarillo Webcasting Alpha Media - Aurora Webcasting Alpha Media - Austin-Albert Lea Webcasting Alpha Media - Bakersfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Biloxi - Gulfport, MS Webcasting Alpha Media - Brookings Webcasting Alpha Media - Cameron - Bethany Webcasting Alpha Media - Canton Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbia, SC Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbus Webcasting Alpha Media - Dayton, Oh Webcasting Alpha Media - East Texas Webcasting Alpha Media - Fairfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Far East Bay Webcasting Alpha Media -

California NEWS SERVICE (June–December) 2007 Annual Report

cans california NEWS SERVICE (June–December) 2007 annual report “Appreciate it’s California- STORY BREAKOUT NUMBER OF RADIO/SPANISH STORIES STATION AIRINGS* specific news…Easy Budget Policy & Priorities 2/1 131 to use…Stories are Children’s Issues 4/3 235 timely…It’s all good…Send Citizenship/Representative Democracy 2 more environment and 130 Civil Rights 3/1 education…Covers stories 160 Community Issues below the threshold of 1 18 the larger news services… Education 4/2 253 Thanks.” Endangered Species/Wildlife 1/1 0 Energy Policy 1 52 California Broadcasters Environment 4/1 230 Global Warming/Air Quality 10/2 574 Health Issues 13/7 “PNS has helped us to 1,565 Housing/Homelessness 7/3 educate Californians on 353 Human Rights/Racial Justice the needs of children 4 264 and families in ways we Immigrant Issues 3/1 128 could have never done on International Relief 5 234 our own by providing an Oceans 2 129 innovative public service Public Lands/Wilderness 6/1 306 that enables us to reach Rural/Farming 2 128 broad audiences and Senior Issues 1/1 54 enhance our impact.” Sustainable Agriculture 1 88 Evan Holland Totals 76/24 5,032 Communications Associate Children’s Defense Fund * Represents the minimum number of times stories were aired. California Launched in June, 2007, the California News Service produced 76 radio and online news stories in the fi rst seven months which aired more than 5,032 times on 215 radio stations in California and 1,091 nationwide. Additionally, 24 Spanish stories were produced. Public News Service California News Service 888-891-9416 800-317-6701 fax 208-247-1830 fax 916-290-0745 * Represents the [email protected] number of times stories were aired. -

Federal Communications Commission FCC 08-3 Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission FCC 08-3 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BTCCT-20061212AVR Communications, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CCF, et al. (Transferors) ) BTCH-20061212BYE, et al. and ) BTCH-20061212BZT, et al. Shareholders of Thomas H. Lee ) BTC-20061212BXW, et al. Equity Fund VI, L.P., ) BTCTVL-20061212CDD Bain Capital (CC) IX, L.P., ) BTCH-20061212AET, et al. and BT Triple Crown Capital ) BTC-20061212BNM, et al. Holdings III, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CDE, et al. (Transferees) ) BTCCT-20061212CEI, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212CEO For Consent to Transfers of Control of ) BTCH-20061212AVS, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212BFW, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting – Fresno, LLC ) BTC-20061212CEP, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting Operations, LLC; ) BTCH-20061212CFF, et al. AMFM Broadcasting Licenses, LLC; ) BTCH-20070619AKF AMFM Radio Licenses, LLC; ) AMFM Texas Licenses Limited Partnership; ) Bel Meade Broadcasting Company, Inc. ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; ) CC Licenses, LLC; CCB Texas Licenses, L.P.; ) Central NY News, Inc.; Citicasters Co.; ) Citicasters Licenses, L.P.; Clear Channel ) Broadcasting Licenses, Inc.; ) Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; and Jacor ) Broadcasting of Colorado, Inc. ) ) and ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BAL-20070619ABU, et al. Communications, Inc. (Assignors) ) BALH-20070619AKA, et al. and ) BALH-20070619AEY, et al. Aloha Station Trust, LLC, as Trustee ) BAL-20070619AHH, et al. (Assignee) ) BALH-20070619ACB, et al. ) BALH-20070619AIT, -

For Public Inspection Comprehensive

REDACTED – FOR PUBLIC INSPECTION COMPREHENSIVE EXHIBIT I. Introduction and Summary .............................................................................................. 3 II. Description of the Transaction ......................................................................................... 4 III. Public Interest Benefits of the Transaction ..................................................................... 6 IV. Pending Applications and Cut-Off Rules ........................................................................ 9 V. Parties to the Application ................................................................................................ 11 A. ForgeLight ..................................................................................................................... 11 B. Searchlight .................................................................................................................... 14 C. Televisa .......................................................................................................................... 18 VI. Transaction Documents ................................................................................................... 26 VII. National Television Ownership Compliance ................................................................. 28 VIII. Local Television Ownership Compliance ...................................................................... 29 A. Rule Compliant Markets ............................................................................................ -

KGB-FM, KHTS-FM, KIOZ, KLSD, KMYI, KOGO, KSSX EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT August 1, 2016 - July 31, 2017

Page: 1/9 KGB-FM, KHTS-FM, KIOZ, KLSD, KMYI, KOGO, KSSX EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT August 1, 2016 - July 31, 2017 I. VACANCY LIST See Section II, the "Master Recruitment Source List" ("MRSL") for recruitment source data Recruitment Sources ("RS") RS Referring Job Title Used to Fill Vacancy Hiree Desktop Support Technician 1-14, 16-27, 29-36 7 Account Executive 1-12, 16-36 7 Outside Account Executive 1-6, 8-13, 16-36 12 Morning Show Producer 1-13, 15-27, 29-37 15 On Air Talent 1-6, 8-12, 15-27, 29-36 15 Account Executive 1-12, 16-27, 29-36 7 This Report was modified in August 2017 to address reporting issues. Page: 2/9 KGB-FM, KHTS-FM, KIOZ, KLSD, KMYI, KOGO, KSSX EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT August 1, 2016 - July 31, 2017 II. MASTER RECRUITMENT SOURCE LIST ("MRSL") Source Entitled No. of Interviewees RS to Vacancy Referred by RS RS Information Number Notification? Over (Yes/No) Reporting Period Academy of Radio & TV Broadcasting 16052 Beach Blvd. Suite 263-N Huntington Beach, California 92647 1 Phone : 714-842-0100 Y 0 Url : www.arbradio.com Email : [email protected] Doreen n/a AMFM Jobs/Broadcast Employment Services P.O. Box 4116 Oceanside, California 92052 Phone : 760-754-8177 2 Url : www.amfmjobs.com N 0 Fax : 1-760-754-2115 Mark Holloway Manual Posting California Broadcasters Assoc. 915 "L" Street Suite #1150 Sacramento, California 95814 3 Phone : 916-444-2237 N 0 Url : http://www.yourcba.com Joe Berry Manual Posting California Department of Veterans Affairs 8810 Rio San Diego Dr San Diego, California 92108 4 Phone : (858) 505-6451 Y 0 Url : www.calvet.ca.gov Email : [email protected] Simon Marquez Center for Employment Training 4153 Market Street San Diego, California 92102-3500 5 Phone : 619-233-6829 Y 0 Url : www.cetweb.org Email : [email protected] S Watchmen Diversity Solutions P.O. -

A Can of Worms

A CAN OF WORMS Pirate Radio as Public Intransigence on the Public Airwaves by John Nathan Anderson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Journalism and Mass Communication) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON 2004 APPROVED ____________________________ James L. Baughman, Professor and Director ____________________________ Robert E. Drechsel, Professor ____________________________ Douglas M. McLeod, Professor and Advisor Contents Preface i Chapter 1. UNLICENSED BROADCASTING AS RADIO HISTORY 1 Scope of Study 3; Organizational Outline of Chapters 5; Overview of Source Material 8; Notes to Chapter 1 14 Chapter 2. CONTEMPORARY TREATMENT OF UNLICENSED BROADCASTING 16 Real-World Constraints on FCC Enforcement 18; Engagement at the Administrative Level 21; Notes to Chapter 2 30 Chapter 3. EARLY RADIO LICENSING AUTHORITY: A CRISIS OF CONFIDENCE 36 1912-1927: Undermined from the Inside 36; 1927/34 Legislation, “Public interest, convenience, and necessity,” and “Access” to the Airwaves 41; Notes to Chapter 3 46 Chapter 4. LEGAL REFINEMENT OF FCC LICENSING AUTHORITY 50 Bedrocks Established in Case Law, 1943-1969 55; FCC License Authority and Enforcement Effectiveness, 1970-1989 60; Notes to Chapter 4 67 Chapter 5. MICRORADIO: FOCUSED CHALLENGE TO THE LICENSING REGIME 72 Stephen Dunifer and Free Radio Berkeley’s “Can of Worms” 73; Other Notable Microradio Cases 78; Microradio and FCC Field Enforcement 82; Notes to Chapter 5 88 Chapter 6. THE FCC AND LPFM 95 Congressional Meddling Into LPFM -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored Call Letters Market Station Name Format WAPS-FM AKRON, OH 91.3 THE SUMMIT Triple A WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRQK-FM AKRON, OH ROCK 106.9 Mainstream Rock WONE-FM AKRON, OH 97.5 WONE THE HOME OF ROCK & ROLL Classic Rock WQMX-FM AKRON, OH FM 94.9 WQMX Country WDJQ-FM AKRON, OH Q 92 Top Forty WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary WPYX-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY PYX 106 Classic Rock WGNA-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY COUNTRY 107.7 FM WGNA Country WKLI-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 100.9 THE CAT Country WEQX-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 102.7 FM EQX Alternative WAJZ-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY JAMZ 96.3 Top Forty WFLY-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY FLY 92.3 Top Forty WKKF-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY KISS 102.3 Top Forty KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary KZRR-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM KZRR 94 ROCK Mainstream Rock KUNM-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM COMMUNITY RADIO 89.9 College Radio KIOT-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM COYOTE 102.5 Classic Rock KBQI-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM BIG I 107.9 Country KRST-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 92.3 NASH FM Country KTEG-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 104.1 THE EDGE Alternative KOAZ-AM ALBUQUERQUE, NM THE OASIS Smooth Jazz KLVO-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 97.7 LA INVASORA Latin KDLW-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM ZETA 106.3 Latin KKSS-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM KISS 97.3 FM