Daniel Gookin, the Praying Indians, and King Philip’S War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gookin's History of the Christian Indians

AN HISTORICAL ACCOUNT OF THE DOINGS AND SUFFERINGS OF THE CHRISTIAN INDIANS IN NEW ENGLAND, IN THE YEARS 1675, 1676, 1677 IMPARTIALLY DRAWN BY ONE WELL ACQUAINTED WITH THAT AFFAIR, A ND PRESENTED UNTO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE THE CORPORATION RESIDING IN LONDON, APPOINTED BY THE KING'S MOST EXCELLENT MAJESTY FOR PROMOTING THE GOSPEL AMONG THE INDIANS IN AMERICA. PRELIMINARY NOTICE. IN preparing the following brief sketch of the principal incidents in the life of the author of “The History of the Christian Indians,” the Publishing Committee have consulted the original authorities cited by the -American biographical writers, and such other sources of information as were known to them, for the purpose of insuring greater accuracy; but the account is almost wholly confined to the period of his residence in New England, and is necessarily given in the most concise manner. They trust, that more ample justice will yet be done to his memory by the biographer and the historian. DANIEL GOOKIN was born in England, about A. D. 1612. As he is termed “a Kentish soldier” by one of his contemporaries, who was himself from the County of Kent, 1 it has been inferred, with good reason, that Gookin was a native of that county. In what year he emigrated to America, does not clearly appear; but he is supposed to have first settled in the southern colony of Virginia, from whence he removed to New England. Cotton Mather, in his memoir of Thompson, a nonconformist divine of Virginia, has the following quaint allusion to our author “A constellation of great converts there Shone round him, and his heavenly glory were. -

The Legacies of King Philip's War in the Massachusetts Bay Colony

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1987 The legacies of King Philip's War in the Massachusetts Bay Colony Michael J. Puglisi College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Puglisi, Michael J., "The legacies of King Philip's War in the Massachusetts Bay Colony" (1987). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623769. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-f5eh-p644 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. For example: • Manuscript pages may have indistinct print. In such cases, the best available copy has been filmed. • Manuscripts may not always be complete. In such cases, a note will indicate that it is not possible to obtain missing pages. • Copyrighted material may have been removed from the manuscript. In such cases, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is also filmed as one exposure and is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 35mm slide or as a 17”x 23” black and white photographic print. -

Proceedings of the Semi-Annual Meeting

Proceedings of the Semi-annual Meeting APRIL iS, I95I AT THE CLUB OV ODD VOLUMES, BOSTON HE semi-annual meeting of the Anieric^in Antiquarian TSociety was held at the Club of Odd Volumes, jj Mount \'ernon Street, Boston, Massachusetts, April 18, 1951, at io.45 o'clock. Samuei Eliot Morison, President of the Society, presided at the meeting. The following members were present; John MeKinstry Mcrriam, George Parker Winship, Clarence Saunders Brigham, Samuel Eliot Morison, Daniel Waldo Lincoln, Mark Antony DeWolfe Howe, Russeil Sturgis i^aine, James Melville Hunnewcll, Stephen Willard Phillips, Stewart Mitchell, Edward Larocque Tinker, Claude Moore I'\icss, Foster Stearns, CiifTord Kenyon Shipton, Theron Johnson Damon, Keyes DeWitt Melcalf, Albert White Rice, Hamilton \'aughan Bail, William Greene Roelker, Henry Rouse V'iets, Walter Muir Whitehiil, Samuel Eoster Damon, William Alexander Jackson, Roger Woicott, Ernest Caulfield, George Russeli Stobbs, Arthur Adams, Richard LeBaron Bowen, Bertram Kimball Little, Caricton Rubira Richmond, Philip Howard Cook, Theodore Bolton, L Bernard Coiien, Harris Dunscombe Colt, Jr., Elmer Tindall Hutchinson. The Secretary read the calí for the meeting, and it was voted to dispense with the reading of the records of the Annual Meeting of October, 1950. 2 AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY [April, The Director read the report of the Council. It was voted to accept the report and refer it to the Committee on Publications. The election of new members being in order, the President announced the following recommendations by the Council for membership in the Society: Lyman Henry Butterfield, Princeton, N. J. Arthur Harrison Cole, Cambridge, Mass. George Talbot Goodspeed, Boston, Mass. -

Early Puritanism in the Southern and Island Colonies

Early Puritanism in the Southern and Island Colonies BY BABETTE M. LEVY Preface NE of the pleasant by-products of doing research O work is the realization of how generously help has been given when it was needed. The author owes much to many people who proved their interest in this attempt to see America's past a little more clearly. The Institute of Early American History and Culture gave two grants that enabled me to devote a sabbatical leave and a summer to direct searching of colony and church records. Librarians and archivists have been cooperative beyond the call of regular duty. Not a few scholars have read the study in whole or part to give me the benefit of their knowledge and judgment. I must mention among them Professor Josephine W, Bennett of the Hunter College English Department; Miss Madge McLain, formerly of the Hunter College Classics Department; the late Dr. William W. Rockwell, Librarian Emeritus of Union Theological Seminary, whose vast scholarship and his willingness to share it will remain with all who knew him as long as they have memories; Professor Matthew Spinka of the Hartford Theological Sem- inary; and my mother, who did not allow illness to keep her from listening attentively and critically as I read to her chapter after chapter. All students who are interested 7O AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY in problems concerning the early churches along the Atlantic seaboard and the occupants of their pulpits are indebted to the labors of Dr. Frederick Lewis Weis and his invaluable compendiums on the clergymen and parishes of the various colonies. -

The Beginning of Winchester on Massachusett Land

Posted at www.winchester.us/480/Winchester-History-Online THE BEGINNING OF WINCHESTER ON MASSACHUSETT LAND By Ellen Knight1 ENGLISH SETTLEMENT BEGINS The land on which the town of Winchester was built was once SECTIONS populated by members of the Massachusett tribe. The first Europeans to interact with the indigenous people in the New Settlement Begins England area were some traders, trappers, fishermen, and Terminology explorers. But once the English merchant companies decided to The Sachem Nanepashemet establish permanent settlements in the early 17th century, Sagamore John - English Puritans who believed the land belonged to their king Wonohaquaham and held a charter from that king empowering them to colonize The Squaw Sachem began arriving to establish the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Local Tradition Sagamore George - For a short time, natives and colonists shared the land. The two Wenepoykin peoples were allies, perhaps uneasy and suspicious, but they Visits to Winchester were people who learned from and helped each other. There Memorials & Relics were kindnesses on both sides, but there were also animosities and acts of violence. Ultimately, since the English leaders wanted to take over the land, co- existence failed. Many sachems (the native leaders), including the chief of what became Winchester, deeded land to the Europeans and their people were forced to leave. Whether they understood the impact of their deeds or not, it is to the sachems of the Massachusetts Bay that Winchester owes its beginning as a colonized community and subsequent town. What follows is a review of written documentation KEY EVENTS IN EARLY pertinent to the cultural interaction and the land ENGLISH COLONIZATION transfers as they pertain to Winchester, with a particular focus on the native leaders, the sachems, and how they 1620 Pilgrims land at Plymouth have been remembered in local history. -

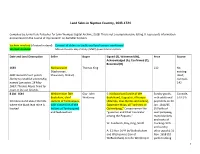

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country.Pdf

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country, 1643-1724 Compiled by Jenny Hale Pulsipher for John Wompas Digital Archive, 2018. This is not a comprehensive listing. It represents information encountered in the course of my research on Swindler Sachem. Sachem involved (if noted in deed) Consent of elders or traditional land owners mentioned Woman involved Massachusetts Bay Colony (MBC) government actions Date and Land Description Seller Buyer Signed (S), Witnessed (W), Price Source Acknowledged (A), ConFirmed (C), Recorded (R) 1643 Nashacowam Thomas King £12 No [Nashoonan, existing MBC General Court grants Shawanon, Sholan] deed; liberty to establish a township, Connole, named Lancaster, 18 May 142 1653; Thomas Noyes hired by town to lay out bounds. 8 Oct. 1644 Webomscom [We Gov. John S: Nodowahunt [uncle of We Sundry goods, Connole, Bucksham, chief Winthrop Bucksham], Itaguatiis, Alhumpis with additional 143-145 10 miles round about the hills sachem of Tantiusques, [Allumps, alias Hyems and James], payments on 20 where the black lead mine is with consent of all the Sagamore Moas, all “sachems of Jan. 1644/45 located Indians at Tantiusques] Quinnebaug,” Cassacinamon the (10 belts of and Nodowahunt “governor and Chief Councelor wampampeeg, among the Pequots.” many blankets and coats of W: Sundanch, Day, King, Smith trucking cloth and sundry A: 11 Nov. 1644 by WeBucksham other goods); 16 and Washcomos (son of Nov. 1658 (10 WeBucksham) to John Winthrop Jr. yards trucking 1 cloth); 1 March C: 20 Jan. 1644/45 by Washcomos 1658/59 to Amos Richardson, agent for John Winthrop Jr. (JWJr); 16 Nov. 1658 by Washcomos to JWJr.; 1 March 1658/59 by Washcomos to JWJr 22 May 1650 Connole, 149; MD, MBC General Court grants 7:194- 3200 acres in the vicinity of 195; MCR, LaKe Quinsigamond to Thomas 4:2:111- Dudley, esq of Boston and 112 Increase Nowell of Charleston [see 6 May and 28 July 1657, 18 April 1664, 9 June 1665]. -

Indigenous Reactions to Religious Colonialism in Seventeenth-Century New England, New France, and New Mexico

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses July 2020 Our Souls are Already Cared For: Indigenous Reactions to Religious Colonialism in Seventeenth-Century New England, New France, and New Mexico Gail Coughlin University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the Canadian History Commons, European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, Latin American History Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, Other History Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Coughlin, Gail, "Our Souls are Already Cared For: Indigenous Reactions to Religious Colonialism in Seventeenth-Century New England, New France, and New Mexico" (2020). Masters Theses. 898. https://doi.org/10.7275/17285938 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/898 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Our Souls Are Already Cared For: Indigenous Reactions to Religious Colonialism in Seventeenth-Century New England, New France, and New Mexico A Thesis Presented by GAIL M. COUGHLIN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree -

Daniel Gookin

PEOPLE MENTIONED IN WALDEN PEOPLE MENTIONED IN A WEEK PEOPLE OF A WEEK AND WALDEN: DANIEL GOOKIN “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY People of A Week and Walden “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” HDT WHAT? INDEX PEOPLE OF A WEEK AND WALDEN:DANIEL GOOKIN PEOPLE MENTIONED IN WALDEN 1612 December 6, Sunday (Old Style): Daniel Gookin had been born, perhaps in County Cork, Ireland, in the latter part of this year, as the 3d son of Daniel Gookin of County Kent and County Cork and Mary (or Mariam) Byrd (or Birde) Gookin of Saffron Walden in Essex, a couple that had been married in Canterbury Cathedral because of the fact that the bride’s father, the Reverend Richard Byrd, DD, was one of the Canons of that Cathedral. On this day the newborn was baptized at the church of St. Augustine-the-Less (which is to say, this was not the Cathedral Church of St Augustine at College Green on the south side of Bristol) in Bristol, Northbourne, County Kent. Daniel and Mary (Byrd) Gookin had five sons. Richard, the eldest, was born about 1609 and named after his grandfather, Dr. Byrd. At the time of his father’s death he was apparently still a member of the paternal household, being described in the administrator’s bond as “Richard Gookin of St. Finn Barre, Cork, Gent.,” but as he did not serve as one of the administrators it may be that he was engaged in some occupation that made it impracticable. Nothing has been learned about his career, though it is certain that he died before 1655, and fair to presume that he married, since he alone of all the members of the family could have been the father of “John Gookin of St. -

Daniel Gookin, 1612-1687, Assistant and Major General of The

- lit H>if>,"w/v 1- ^1 Kr»,»»J-*f» > K LIBRARY OF CONGRESS D0Q201H5Qia i^^ ^A V"^'" A^5 'C, ^j. -^ .5 -^^ •0^%, A- ^^ "^. .A'' S^c \.^ .-^'^ ,A> '^r. -^ % ^V> H -7^ ^^. 't/- .<> ^. ,V J' ^^ >0 o. • ^ ^r.. .v'>- %^^ MAJOR GENERAL DANIEL GOOKIN Edition two hundred and two numbered copies, of which this is Number DANIEL GOOKIN 1612-1687 ASSISTANT AND MAJOR GENERAL OF THE MASSACHUSETTS BAY COLONY HIS LIFE AND LETTERS AND SOME ACCOUNT OF HIS ANCESTRY ^VlRJUSQUEj 3 \. COPYRIGHT, I912 FREDERICK WILLIAM GOOKIN cy CCLA3 4.JOGS ^ i ^ TO THE MEMORY OF JOHN WINGATE THORNTON DESCENDANT AND ARDENT ADMIRER OF DANIEL GOOKIN PREFACE HAT no extended biography of Daniel Gookin has heretofore been published is without doubt attributable to the paucity of the available mate- rial. About 1840 Mr. John Wingate Thornton began to gather information about his distin- guished ancestor, and in 1847 the facts he had been able to get together were embodied in an article upon "The Gookin Family," printed that year in the first volume of "The New England Historical and Genealogi- cal Register." For more than thirty years Mr. Thornton was an eager gleaner of every item he could discover concerning the " grand old American patriarch and sage." Though, to his deep regret, he was unable to carry out his design of writing a life of Daniel Gookin, by his early researches he laid a foun- dation for which I am greatly indebted. It is now thirty-six years since Mr. Thornton resigned his cherished task to my hands and I began the collection of data for the present work. -

The Puritan Experiment in Virginia, 1607-1650

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1999 The Puritan Experiment in Virginia, 1607-1650 Kevin Butterfield College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History of Religion Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Butterfield, eK vin, "The Puritan Experiment in Virginia, 1607-1650" (1999). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626229. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-ptz3-sb69 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PURITAN EXPERIMENT IN VIRGINIA, 1607-1650 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Kevin Butterfield 1999 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts .. , Kevin ifctterfield Approved, June 1999 ohn Selbw c 9 b»*+, A k uSj l _______ James Axtell 4 * 4 / / ^ Dale Hoak TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT Tv INTRODUCTION 3 PART ONE 7 PART TWO 28 CONCLUSION 49 NOTES 52 BIBLIOGRAPHY 63 iii ABSTRACT Puritanism played an important role in seventeenth-century Virginia. Not limited to New England, Puritans settled in various locales in the New World, including Virginia, mostly south of the James River. -

Pecoraro Abstract Final

“MR. GOOKIN OUT OF IRELAND, WHOLLY UPON HIS OWN ADVENTURE”: AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL STUDY OF INTERCOLONIAL AND TRANSATLANTIC CONNECTIONS IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY (Order No. _____) Boston University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, 2015 Major Professor: Mary C. Beaudry, Professor of Archaeology, Anthropology, and Gastronomy ABSTRACT English colonization of Virginia is characterized as boldly intrusive, spreading quickly from the first toehold at Jamestown into the hinterlands and leading to open hostility with native peoples almost from the start. In this dissertation, I examine links between practices in the home country and Virginia through the actions and backstory of one particular colonizer: Daniel Gookin Jr. (1612–1687), an English Puritan adventurer who migrated from Ireland to Virginia and later to Maryland and Massachusetts. I use archaeological evidence from both Ireland and southeastern Virginia to demonstrate that Irish influences on 17th-century colonial projects in Virginia were greater than previously thought. Prior to emigrating to the colonies, Gookin was one of a number of Puritans owning property in County Cork, Ireland. I surveyed the ruins of 12 fortified houses and four archaeological sites in County Cork that were either owned or leased by Gookin, or were properties of his associates. In Virginia, Gookin is credited with building the Nansemond Fort Site (44SK192), a ca.1637 inland fortified bawn in Suffolk. The Nansemond Fort’s similarities with bawns from the same period in Ireland’s Munster Plantation indicate that the Virginia property was also built for the dual purposes of personal defense and animal husbandry. The plantation system Gookin learned in Ireland he replicated in North America—raising cattle and corn for transatlantic and intercolonial provisioning, maintaining a tight trading network of Puritan family members in Ireland and Puritans in other British colonies, and negotiation with indigenous people—resulting in his acquisition of three plantations in Maryland and Virginia and five in New England. -

Praying Indians' on Deer Island, Massachusetts Bay Colony, 1675-1676

Article The Sovereignty of Transmotion in a State of Exception: Lessons from the Internment of ‘Praying Indians' on Deer Island, Massachusetts Bay Colony, 1675-1676 MADSEN, Deborah Lea Abstract Settler colonialism is a structure rather than an event, according to recent theorists such as Patrick Wolfe, a process marked by the clearing of colonial space through the “logic of elimination”: the separation, dispossession, removal, and disappearance of indigenous peoples from their homelands. Metacom's War offers an early instance of this process. Among the many grievances that Metacom presented to the deputy governor of Rhode Island colony, John Easton, during their negotiations in June 1675 were the increasing pace of land loss, the threat posed by forcible Christianization, and the loss of tribal jurisdiction. These grievances represent two major dynamics of later US settler colonialism: dispossession and coercive acculturation. However, at the outset of hostilities, the settler colonies employed a further strategy of Native confinement, culminating in the internment of so-called “Praying Indians” on Deer Island in Boston Harbor. Atrocities committed against Christian Indians have a special resonance: as subjects of the English Crown, a fact acknowledged by Metacom in his negotiations with Easton, these [...] Reference MADSEN, Deborah Lea. The Sovereignty of Transmotion in a State of Exception: Lessons from the Internment of ‘Praying Indians’ on Deer Island, Massachusetts Bay Colony, 1675-1676. Transmotion, 2015, vol. 1, no. 1, p. 23-47 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:55724 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 Transmotion Vol 1, No 1 (2015) The Sovereignty of Transmotion in a State of Exception: Lessons from the Internment of ‘Praying Indians’ on Deer Island, Massachusetts Bay Colony, 1675-1676 DEBORAH L.