The Universal Design File: Designing for People of All Ages and Abilities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning Curriculum in Art and Design

Planning Curriculum in Art and Design Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction Planning Curriculum in Art and Design Melvin F. Pontious (retired) Fine Arts Consultant Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction Tony Evers, PhD, State Superintendent Madison, Wisconsin This publication is available from: Content and Learning Team Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction 125 South Webster Street Madison, WI 53703 608/261-7494 cal.dpi.wi.gov/files/cal/pdf/art.design.guide.pdf © December 2013 Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction does not discriminate on the basis of sex, race, color, religion, creed, age, national origin, ancestry, pregnancy, marital status or parental status, sexual orientation, or disability. Foreword Art and design education are part of a comprehensive Pre-K-12 education for all students. The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction continues its efforts to support the skill and knowledge development for our students across the state in all content areas. This guide is meant to support this work as well as foster additional reflection on the instructional framework that will most effectively support students’ learning in art and design through creative practices. This document represents a new direction for art education, identifying a more in-depth review of art and design education. The most substantial change involves the definition of art and design education as the study of visual thinking – including design, visual communications, visual culture, and fine/studio art. The guide provides local, statewide, and national examples in each of these areas to the reader. The overall framework offered suggests practice beyond traditional modes and instead promotes a more constructivist approach to learning. -

Orthotics Fact Sheet

Foundations of Pediatric Orthotics FACT The goal of this fact sheet is to provide a reference highlighting key points of orthotic management in children. Additional information on pediatric orthotic management can be located in the Atlas of Orthoses and Assistive Devices, edited by the American Acad- emy of Orthopedic Surgeons, and Lower Extremity Orthotic Intervention for the Pediatric SHEET Client in Topics in Physical Therapy: Pediatrics, edited by the American Physical Therapy Association. What Is an Orthosis? An orthosis is an external device with controlling forces to improve body alignment, improve function, immobilize the injured area, prevent or improve a deformity, protect a joint or limb, limit or reduce pain, and/or provide proprioceptive feedback. Orthoses are named for the part of the body they cover. Orthoses can be custom molded and custom fitted (custom fitted from prefabricated orthoses or off the shelf). Orthoses are classified as durable medical devices (DME) and require L-codes for insurance reimbursement. A prescription signed by a physician is usually required for insurance reimbursement for custom-molded and custom-fit orthoses. Who Designs and Provides Orthoses? • Certified orthotists have formal education in biomechanics and mate- rial sciences required in designing custom devices. They are nation- ally board certified, and 11 states require licensure to provide custom devices. There are approximately 3,000 certified orthotists in the US, with a limited number of orthotists specializing in pediatrics. Pediatric orthotists evaluate the child, cast the child, modify the mold, fabricate the orthosis, and custom fit the orthosis to the child. • Physical therapists are trained in the function of orthoses and will frequently fit and measure orthoses. -

Entertainment & Syndication Fitch Group Hearst Health Hearst Television Magazines Newspapers Ventures Real Estate & O

hearst properties WPBF-TV, West Palm Beach, FL SPAIN Friendswood Journal (TX) WYFF-TV, Greenville/Spartanburg, SC Hardin County News (TX) entertainment Hearst España, S.L. KOCO-TV, Oklahoma City, OK Herald Review (MI) & syndication WVTM-TV, Birmingham, AL Humble Observer (TX) WGAL-TV, Lancaster/Harrisburg, PA SWITZERLAND Jasper Newsboy (TX) CABLE TELEVISION NETWORKS & SERVICES KOAT-TV, Albuquerque, NM Hearst Digital SA Kingwood Observer (TX) WXII-TV, Greensboro/High Point/ La Voz de Houston (TX) A+E Networks Winston-Salem, NC TAIWAN Lake Houston Observer (TX) (including A&E, HISTORY, Lifetime, LMN WCWG-TV, Greensboro/High Point/ Local First (NY) & FYI—50% owned by Hearst) Winston-Salem, NC Hearst Magazines Taiwan Local Values (NY) Canal Cosmopolitan Iberia, S.L. WLKY-TV, Louisville, KY Magnolia Potpourri (TX) Cosmopolitan Television WDSU-TV, New Orleans, LA UNITED KINGDOM Memorial Examiner (TX) Canada Company KCCI-TV, Des Moines, IA Handbag.com Limited Milford-Orange Bulletin (CT) (46% owned by Hearst) KETV, Omaha, NE Muleshoe Journal (TX) ESPN, Inc. Hearst UK Limited WMTW-TV, Portland/Auburn, ME The National Magazine Company Limited New Canaan Advertiser (CT) (20% owned by Hearst) WPXT-TV, Portland/Auburn, ME New Canaan News (CT) VICE Media WJCL-TV, Savannah, GA News Advocate (TX) HEARST MAGAZINES UK (A+E Networks is a 17.8% investor in VICE) WAPT-TV, Jackson, MS Northeast Herald (TX) VICELAND WPTZ-TV, Burlington, VT/Plattsburgh, NY Best Pasadena Citizen (TX) (A+E Networks is a 50.1% investor in VICELAND) WNNE-TV, Burlington, VT/Plattsburgh, -

'Design for All' Versus 'One-Size-Fits-All': the Case Of

‘Design for All’ versus ‘One-Size-Fits-All’: the Case of Cultural Heritage 1 2 Daniela Fogli , Alberto Arenghi 1Dipartimento di Ingegneria dell'Informazione Università degli Studi di Brescia, Brescia, Italy [email protected] 2Dipartimento di Ingegneria Civile, Architettura, Territorio e Ambiente e di Matematica Università degli Studi di Brescia, Brescia, Italy [email protected] Abstract. This paper would like to discuss the design trade-offs that might emerge during the development of technological solutions for promoting and enhancing the fruition of cultural heritage. To this aim, the paper briefly describes the UniBSArt4All project, which employs advanced interactive technologies, such as artwork recognition and wireless sensors, to obtain engaging and accessible visitor experiences customized to different users’ profiles. By reflecting on the project development and its preliminary results, the paper finally proposes a meta-design approach to inclusive design in the CH domain. Keywords: Cultural heritage, augmented reality, beacon, end-user development, meta-design, inclusive design, design for all 1 Introduction In our everyday life, we often encounter trade-offs, namely situations where we need to renounce to something in order to gain something else. Problem solving usually represents such a situation, in which a solution must be designed by taking into account both the goals one would like to satisfy and the different constraints that impose choosing among those goals. Therefore, usually design “is the identification, discussion and resolution of trade-offs” [15]. Indeed, as underlined by Gerhard Fischer, a design problem does not have a correct solution or a right answer, but the solution or the answer depends on the values and interests of the involved stakeholders [6][7]. -

Lower Extremity Orthoses in Children with Spastic Quadriplegic Cerebral Palsy Implications for Nurses, Parents, and Caregivers

NOR200210.qxd 5/5/11 5:53 PM Page 155 Lower Extremity Orthoses in Children With Spastic Quadriplegic Cerebral Palsy Implications for Nurses, Parents, and Caregivers Kathleen Cervasio Understanding trends in the prevalence of children with cerebral prevalence for cerebral palsy in the United States is palsy is vital to evaluating and estimating supportive services for 2.4 per 1,000 children, an increase over previously re- children, families, and caregivers. The majority of children with ported data (Hirtz, Thurman, Gwinn-Hardy, Mohammad, cerebral palsy require lower extremity orthoses to stabilize their Chaudhuri, & Zalusky, 2007). Cerebral palsy is primar- muscles. The pediatric nurse needs a special body of knowledge ily a disorder of movement and posture originating in to accurately assess, apply, manage, teach, and evaluate the use the central nervous system with an incidence of 2.5 per 1,000 live births with spastic quadriplegia being the of lower extremity orthoses typically prescribed for this vulnera- common type of cerebral palsy (Blair & Watson, 2006). ble population. Inherent in caring for these children is the need This nonprogressive neurological disorder is defined as to teach the child, the family, and significant others the proper a variation in movement, coordination, posture, and application and care of the orthoses used in hospital and com- gait resulting from brain injury around birth (Blair & munity settings. Nursing literature review does not provide a Watson, 2006). Numerous associated comorbidities are basis for evidence in designing and teaching orthopaedic care usually present with cerebral palsy requiring various for children with orthoses. A protocol for orthoses management interventions. -

Linking Design Management Skills and Design Function Organization: an Empirical Study of Spanish and Italian Ceramic Tile Producers

CASTELLÓN (SPAIN) LINKING DESIGN MANAGEMENT SKILLS AND DESIGN FUNCTION ORGANIZATION: AN EMPIRICAL STUDY OF SPANISH AND ITALIAN CERAMIC TILE PRODUCERS Ricardo Chiva (1), Joaquín Alegre (2), David Gobert (3), Rafael Lapiedra (1) (1) Universitat Jaume I, (2) Universitat de València, (3) ITC, Universitat Jaume I, ABSTRACT Design management is an increasingly important concept, research into which is very scarce. This paper deals with the fit between design management skills and design function organization, ranging from solely in-house to solely outsourced and including a mixture of the two. We carried out a survey in the Spanish and Italian ceramic tile industry, to which 177 product development managers responded. Our results revealed that companies have different degrees of design management skills depending on the approach to design function organization. Solely in-house design approach companies are the most skilled firms and solely outsourced ones are the least skilled. Despite the fact that the design function has apparently evolved towards outsourcing, this research supports the idea that, under certain conditions, the in-house design department is the best option in order to attain higher degrees of design management skills. Implications of the findings for both academics and practitioners are examined. P.BA - 79 CASTELLÓN (SPAIN) 1. INTRODUCTION In today’s competitive environment, design is becoming increasingly important. Good design, though, does not emerge by accident but as the result of a managed process (Bruce and Bessant, 2002, p. 38). Apart from the development process leading up to the creation of an artifact or product, the concept of design has traditionally involved a series of organizational activities, practices or skills that are required for this development to be achieved (Gorb and Dumas, 1987). -

Ergonomics, Design Universal and Fashion

Work 41 (2012) 4733-4738 4733 DOI: 10.3233/WOR-2012-0761-4733 IOS Press Ergonomics, design universal and fashion Martins, S. B. Dr.ª and Martins, L. B.Dr.b a State University of Londrina, Department of Design, Rodovia Celso Garcia Cid Km. 380 Campus Universitário,86051-970, Londrina, PR, Brazil. [email protected] b Federal University of Pernambuco, Department of Design, Av. Prof. Moraes Rego, 1235, Cidade Universitária, 50670-901, Recife- PE, Brazil. [email protected] Abstract. People who lie beyond the "standard" model of users often come up against barriers when using fashion products, especially clothing, the design of which ought to give special attention to comfort, security and well-being. The principles of universal design seek to extend the design process for products manufactured in bulk so as to include people who, because of their personal characteristics or physical conditions, are at an extreme end of some dimension of performance, whether this is to do with sight, hearing, reach or manipulation. Ergonomics, a discipline anchored on scientific data, regards human beings as the central focus of its operations and, consequently, offers various forms of support to applying universal design in product development. In this context, this paper sets out a reflection on applying the seven principles of universal design to fashion products and clothing with a view to targeting such principles as recommendations that will guide the early stages of developing these products, and establish strategies for market expansion, thereby increasing the volume of production and reducing prices. Keywords: Ergonomics in fashion, universal design, people with disabilities 1. -

A Year of Progress “Every Day You May Make Progress

2007 Annual Report of the Amputee Coalition of America A Year of Progress “Every day you may make progress. Every step may be fruitful. Yet there will stretch out before you an ever- lengthening, ever-ascending, ever-improving path. You know you will never get to the end of the journey. But this, so far from discouraging, only adds to the joy and glory of the climb.” — Sir Winston Churchill 1 our mission To reach out to people with limb loss and to empower them through education, support and advocacy. In Support of Our Mission Advocacy Education ACA advocates for the rights of people with limb ACA publishes inMotion, First Step and other magazines loss or a limb difference. This includes access to, and that comprehensively address areas of interest and delivery of, information, quality care, appropriate concern to amputees and those who care for and about devices, reimbursement, and the services required to them. lead empowered lives. ACA develops and distributes educational resources, ACA promotes full implementation of the Americans booklets, videotapes, and fact sheets to enhance the with Disabilities Act and other legislation that guaran- knowledge and coping skills of people affected by am- tees full participation in society for all people, regard- putation or congenital limb differences. less of disability. ACA’s National Limb Loss Information Center is a com- ACA sensitizes professionals, the general public and prehensive source of information about amputation policymakers to the issues, needs and concerns of and rehabilitation. amputees. ACA provides technical help, resources and training for Support local amputee educational and support organizations. -

Privacy When Form Doesn't Follow Function

Privacy When Form Doesn’t Follow Function Roger Allan Ford University of New Hampshire [email protected] Privacy When Form Doesn’t Follow Function—discussion draft—3.6.19 Privacy When Form Doesn’t Follow Function Scholars and policy makers have long recognized the key role that design plays in protecting privacy, but efforts to explain why design is important and how it affects privacy have been muddled and inconsistent. Tis article argues that this confusion arises because “design” has many different meanings, with different privacy implications, in a way that hasn’t been fully appreciated by scholars. Design exists along at least three dimensions: process versus result, plan versus creation, and form versus function. While the literature on privacy and design has recognized and grappled (sometimes implicitly) with the frst two dimensions, the third has been unappreciated. Yet this is where the most critical privacy problems arise. Design can refer both to how something looks and is experienced by a user—its form—or how it works and what it does under the surface—its function. In the physical world, though, these two conceptions of design are connected, since an object’s form is inherently limited by its function. Tat’s why a padlock is hard and chunky and made of metal: without that form, it could not accomplish its function of keeping things secure. So people have come, over the centuries, to associate form and function and to infer function from form. Software, however, decouples these two conceptions of design, since a computer can show one thing to a user while doing something else entirely. -

Ellies 2018 Finalists Announced

Ellies 2018 Finalists Announced New York, The New Yorker top list of National Magazine Award nominees; CNN’s Don Lemon to host annual awards lunch on March 13 NEW YORK, NY (February 1, 2018)—The American Society of Magazine Editors today published the list of finalists for the 2018 National Magazine Awards for Print and Digital Media. For the fifth year, the finalists were first announced in a 90-minute Twittercast. ASME will celebrate the 53rd presentation of the Ellies when each of the 104 finalists is honored at the annual awards lunch. The 2018 winners will be announced during a lunchtime presentation on Tuesday, March 13, at Cipriani Wall Street in New York. The lunch will be hosted by Don Lemon, the anchor of “CNN Tonight With Don Lemon,” airing weeknights at 10. More than 500 magazine editors and publishers are expected to attend. The winners receive “Ellies,” the elephant-shaped statuettes that give the awards their name. The awards lunch will include the presentation of the Magazine Editors’ Hall of Fame Award to the founding editor of Metropolitan Home and Saveur, Dorothy Kalins. Danny Meyer, the chief executive officer of the Union Square Hospitality Group and founder of Shake Shack, will present the Hall of Fame Award to Kalins on behalf of ASME. The 2018 ASME Award for Fiction will also be presented to Michael Ray, the editor of Zoetrope: All-Story. The winners of the 2018 ASME Next Awards for Journalists Under 30 will be honored as well. This year 57 media organizations were nominated in 20 categories, including two new categories, Social Media and Digital Innovation. -

![[ENTER NAME of PROJECT] PROJECT CHARTER SMALL to MEDIUM PROJECTS [Enter Date] V1.0](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0065/enter-name-of-project-project-charter-small-to-medium-projects-enter-date-v1-0-230065.webp)

[ENTER NAME of PROJECT] PROJECT CHARTER SMALL to MEDIUM PROJECTS [Enter Date] V1.0

[ENTER NAME OF PROJECT] PROJECT CHARTER SMALL TO MEDIUM PROJECTS [Enter Date] V1.0 Campus Planning and Facilities Management – Design and Construction 1276 University of Oregon, Eugene OR 97403-1276 541-346-8292 | fax 541-346-6927 cpfm.uoregon.edu/design-construction An equal-opportunity, affirmative-action institution committed to cultural diversity and compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act PROJECT NAME PROJECT NUMBER TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ………………………………………………………….. 3 Purpose of the Project Charter ………………………………………… 3 2. BASIC PROJECT DELIVERY PROCESS ….……………………………… 4 3. PROJECT OVERVIEW/GOALS ……………………..……………………. 4 4. SCOPE ……………………………………………………………………. 5 4.1 Objectives ………………………………………………………… 5 4.2 Boundaries ……………………………………………………….. 5 5. ASSUMPTIONS AND RISKS ……………………………………………… 5 5.1 Assumptions ……………………………………………………... 5 5.2 Risks ……………………………………………………………... 5 5.3 Exclusions ………………………………………………………… 5 6. DURATION ……………………………………………………………….. 5 5.1Timeline …………………………………………………………... 5 7. BUDGET OPINION …………………………………………………... 6 6.1 Funding Source ………………………………………………..... 6 6.2 Estimate ………………………………………………………..... 6 8. CONTRACT METHODOLOY ………………………………………... …… 7 9. PROJECT ORGANIZATION ……………………………………………… 8 10. FUNDING SOURCES ……………………………………………………. 11 11. PROJECT CHARTER APPROVALS…………………………………….. 12 APPENDIX A: KEY ACRONYMS AND TERMS …………………………….. 13 APPENDIX B: REFERENCE MATERIALS …………………………………. 15 APPENDIX C: PROJECT CHARTER CHANGE TRACKING ........................ 16 Page 3 of 20 PROJECT NAME PROJECT NUMBER 1. INTRODUCTION -

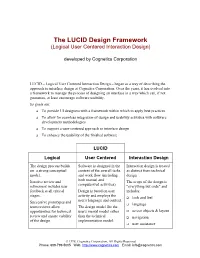

The LUCID Design Framework (Logical User Centered Interaction Design)

The LUCID Design Framework (Logical User Centered Interaction Design) developed by Cognetics Corporation LUCID – Logical User Centered Interaction Design – began as a way of describing the approach to interface design at Cognetics Corporation. Over the years, it has evolved into a framework to manage the process of designing an interface in a way which can, if not guarantee, at least encourage software usability. Its goals are: q To provide UI designers with a framework within which to apply best practices q To allow for seamless integration of design and usability activities with software development methodologies q To support a user-centered approach to interface design q To enhance the usability of the finished software LUCID Logical User Centered Interaction Design The design process builds Software is designed in the Interaction design is treated on a strong conceptual context of the overall tasks as distinct from technical model. and work flow (including design. both manual and Iterative review and The scope of the design is computerized activities). refinement includes user "everything but code" and feedback at all critical Design is based on user includes: stages. activity and employs the q look and feel user's language and context. Successive prototypes and q language team reviews allow The design model fits the opportunities for technical user's mental model rather q screen objects & layout review and ensure viability than the technical q navigation of the design implementation model. q user assistance © 1998, Cognetics Corporation, All Rights Reserved Phone: 609-799-5005 Web: http://www.cognetics.com Email: [email protected] An Introduction to the LUCID Framework Page 2 Over the past 30 years, several techniques for managing software development projects have been developed and documented.