Banking on Thin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jyske Bank H1 2014 Agenda

Jyske Bank H1 2014 Agenda • Jyske Bank in brief • Jyske Banks Performance 1968-2013 • Merger with BRFkredit • Focus in H1 2014 • H1 2014 in figures • Capital Structure • Liquidity • Credit Quality • Strategic Issues • Macro Economy & Danish Banking 2013-2015 • Danish FSA • Fact Book 2 Jyske Bank in brief 3 Jyske Bank in brief Jyske Bank focuses on core business Description Branch Network • Established and listed in 1967 • 2nd largest Danish bank by lending • Total lending of DKK 344bn • 149 domestic branches • Approx. 900,000 customers • Business focus is on Danish private individuals, SMEs and international private and institutional investment clients • International units in Hamburg, Zürich, Gibraltar, Cannes and Weert • A de-centralised organisation • 4,352 employees (end of H1 2013) • Full-scale bank with core operations within retail and commercial banking, mortgage financing, customer driven trading, asset management and private banking • Flexible business model using strategic partnerships within life insurance (PFA), mortgage products (DLR), credit cards (SEB), IT operations (JN Data) and IT R&D (Bankdata) 4 Jyske Bank in brief Jyske Bank has a differentiation strategy “Jyske Differences” • Jyske Bank wants to be Denmark’s most customer-oriented bank by providing high standard personal financial advice and taking a genuine interest in customers • The strategy is to position Jyske Bank as a visible and distinct alternative to more traditional providers of financial services, with regard to distribution channels, products, branches, layout and communication forms • Equal treatment and long term relationships with stakeholders • Core values driven by common sense • Strategic initiatives: Valuebased management Differentiation Risk management Efficiency improvement Acquisitions 5 1990 1996 2002 2006 (Q4) 2011/2012 Jyske Bank performance 1968-2013 6 ROE on opening equity – 1968-2013 Pre-tax profit Average: (ROE on open. -

DXE Liquidity Provider Registered Firms

DXE Liquidity Provider Program Registered Securities European Equities TheCboe following Europe Limited list of symbols specifies which firms are registered to supply liquidity for each symbol in 2021-09-28: 1COVd - Covestro AG Citadel Securities GCS (Ireland) Limited (Program Three) DRW Europe B.V. (Program Three) HRTEU Limited (Program Two) Jane Street Financial Limited (Program Three) Jump Trading Europe B.V. (Program Three) Qube Master Fund Limited (Program One) Societe Generale SA (Program Three) 1U1d - 1&1 AG Citadel Securities GCS (Ireland) Limited (Program Three) HRTEU Limited (Program Two) Jane Street Financial Limited (Program Three) 2GBd - 2G Energy AG Citadel Securities GCS (Ireland) Limited (Program Three) Jane Street Financial Limited (Program Three) 3BALm - WisdomTree EURO STOXX Banks 3x Daily Leveraged HRTEU Limited (Program One) 3DELm - WisdomTree DAX 30 3x Daily Leveraged HRTEU Limited (Program One) 3ITLm - WisdomTree FTSE MIB 3x Daily Leveraged HRTEU Limited (Program One) 3ITSm - WisdomTree FTSE MIB 3x Daily Short HRTEU Limited (Program One) 8TRAd - Traton SE Jane Street Financial Limited (Program Three) 8TRAs - Traton SE Jane Street Financial Limited (Program Three) Cboe Europe Limited is a Recognised Investment Exchange regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Cboe Europe Limited is an indirect wholly-owned subsidiary of Cboe Global Markets, Inc. and is a company registered in England and Wales with Company Number 6547680 and registered office at 11 Monument Street, London EC3R 8AF. This document has been established for information purposes only. The data contained herein is believed to be reliable but is not guaranteed. None of the information concerning the services or products described in this document constitutes advice or a recommendation of any product or service. -

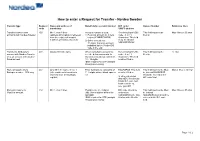

How to Enter a Request for Transfer - Nordea Sweden

How to enter a Request for Transfer - Nordea Sweden Transfer type Request Name and address of Beneficiary’s account number BIC code / Name of banker Reference lines code beneficiary SWIFT address Transfer between own 400 Min 1, max 4 lines Account number is used: Receiving bank’s BIC This field must not be Max 4 lines x 35 char accounts with Nordea Sweden (address information is retrieved 1) Personal account no = pers code - 8 or 11 filled in from the register of account reg no (YYMMDDXXXX) characters. This field numbers of Nordea, Sweden) 2) Other account nos = must be filled in 11 digits. Currency account NDEASESSXXX indicated by the 3-letter ISO code in the end Transfer to third party’s 401 Always fill in the name When using bank account no., Receiving bank’s BIC This field must not be 12 char account with Nordea Sweden see the below comments. In code - 8 or 11 filled in or to an account with another Sweden account nos consist of characters. This field Swedish bank 10 - 15 digits. must be filled in IBAN required for STP (straight through processing) Domestic payments to 402 Only fill in the name in line 1 Enter bankgiro no consisting of BGABSESS. This field This field must not be filled Max 4 lines x 35 char Bankgiro number - SEK only (other address information is 7 - 8 digits without blank spaces must be filled in. in. Instead BGABSESS retrieved from the Bankgiro etc should be entered in the register) In other currencies BIC code field than SEK: Receivning banks BIC code and bank account no. -

Chronology, 1963–89

Chronology, 1963–89 This chronology covers key political and economic developments in the quarter century that saw the transformation of the Euromarkets into the world’s foremost financial markets. It also identifies milestones in the evolu- tion of Orion; transactions mentioned are those which were the first or the largest of their type or otherwise noteworthy. The tables and graphs present key financial and economic data of the era. Details of Orion’s financial his- tory are to be found in Appendix IV. Abbreviations: Chase (Chase Manhattan Bank), Royal (Royal Bank of Canada), NatPro (National Provincial Bank), Westminster (Westminster Bank), NatWest (National Westminster Bank), WestLB (Westdeutsche Landesbank Girozentrale), Mitsubishi (Mitsubishi Bank) and Orion (for Orion Bank, Orion Termbank, Orion Royal Bank and subsidiaries). Under Orion financings: ‘loans’ are syndicated loans, NIFs, RUFs etc.; ‘bonds’ are public issues, private placements, FRNs, FRCDs and other secu- rities, lead managed, co-managed, managed or advised by Orion. New loan transactions and new bond transactions are intended to show the range of Orion’s client base and refer to clients not previously mentioned. The word ‘subsequently’ in brackets indicates subsequent transactions of the same type and for the same client. Transaction amounts expressed in US dollars some- times include non-dollar transactions, converted at the prevailing rates of exchange. 1963 Global events Feb Canadian Conservative government falls. Apr Lester Pearson Premier. Mar China and Pakistan settle border dispute. May Jomo Kenyatta Premier of Kenya. Organization of African Unity formed, after widespread decolonization. Jun Election of Pope Paul VI. Aug Test Ban Take Your Partners Treaty. -

Retirement Strategy Fund 2060 Description Plan 3S DCP & JRA

Retirement Strategy Fund 2060 June 30, 2020 Note: Numbers may not always add up due to rounding. % Invested For Each Plan Description Plan 3s DCP & JRA ACTIVIA PROPERTIES INC REIT 0.0137% 0.0137% AEON REIT INVESTMENT CORP REIT 0.0195% 0.0195% ALEXANDER + BALDWIN INC REIT 0.0118% 0.0118% ALEXANDRIA REAL ESTATE EQUIT REIT USD.01 0.0585% 0.0585% ALLIANCEBERNSTEIN GOVT STIF SSC FUND 64BA AGIS 587 0.0329% 0.0329% ALLIED PROPERTIES REAL ESTAT REIT 0.0219% 0.0219% AMERICAN CAMPUS COMMUNITIES REIT USD.01 0.0277% 0.0277% AMERICAN HOMES 4 RENT A REIT USD.01 0.0396% 0.0396% AMERICOLD REALTY TRUST REIT USD.01 0.0427% 0.0427% ARMADA HOFFLER PROPERTIES IN REIT USD.01 0.0124% 0.0124% AROUNDTOWN SA COMMON STOCK EUR.01 0.0248% 0.0248% ASSURA PLC REIT GBP.1 0.0319% 0.0319% AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR 0.0061% 0.0061% AZRIELI GROUP LTD COMMON STOCK ILS.1 0.0101% 0.0101% BLUEROCK RESIDENTIAL GROWTH REIT USD.01 0.0102% 0.0102% BOSTON PROPERTIES INC REIT USD.01 0.0580% 0.0580% BRAZILIAN REAL 0.0000% 0.0000% BRIXMOR PROPERTY GROUP INC REIT USD.01 0.0418% 0.0418% CA IMMOBILIEN ANLAGEN AG COMMON STOCK 0.0191% 0.0191% CAMDEN PROPERTY TRUST REIT USD.01 0.0394% 0.0394% CANADIAN DOLLAR 0.0005% 0.0005% CAPITALAND COMMERCIAL TRUST REIT 0.0228% 0.0228% CIFI HOLDINGS GROUP CO LTD COMMON STOCK HKD.1 0.0105% 0.0105% CITY DEVELOPMENTS LTD COMMON STOCK 0.0129% 0.0129% CK ASSET HOLDINGS LTD COMMON STOCK HKD1.0 0.0378% 0.0378% COMFORIA RESIDENTIAL REIT IN REIT 0.0328% 0.0328% COUSINS PROPERTIES INC REIT USD1.0 0.0403% 0.0403% CUBESMART REIT USD.01 0.0359% 0.0359% DAIWA OFFICE INVESTMENT -

Aktienyt Novozymes

Aktienyt Novozymes Hold Udfordrende markeder dæmper salgsvæksten Uændret Hold-anbefaling siden 20/04/2016 Vi fastholder vores Hold-anbefaling på Novozymes Dagens regnskab er lidt svagere, end vi havde ventet. Hård priskonkurrence i ’Bioenergi’ og økonomisk Analysedato: 10/08/2016 pressede kunder i ’Landbrug og Foder’ dæmper Novozymes’ salgsvækst. Pris- fastsættelsen af Novozymes-aktien afspejler efter vores vurdering Novozymes’ Aktuel kurs kl. 12:11: kortsigtede forretningsmuligheder. 295,00 DKK Salgsvæksten skuffer i årets 2. kvartal Omsætningen på 3.429 mio. kr. i 2. kvartal 2016 er 3,3% dårligere end vores estimat (-3,5% i Begivenhed: forhold til markedsforventningen). Resultatet af primær drift på 961 mio. kr. i 2. kvartal 2016 er 2,9% under vores estimat (-2,6% i forhold til markedsforventningen). I forhold til vores for- 2. kvartalsregnskab ventning er det specielt salget i divisionerne ’Bioenergi’ og ’Landbrug og Foder’, der viser en svagere end ventet udvikling i 2. kvartal. Novozymes justerer salgsprognosen for 2016 i lokal Seneste analyse: valuta. Selskabet venter nu en salgsvækst i lokal valuta på 2-4% i 2016 mod tidligere 3-5%. 05/08/16 – Vækst i ’Vaskemid- Novozymes forventer, at salgsvæksten i danske kroner forbliver uændret på 1-3% i 2016. ler’ – Tilbagegang i ’Bioenergi’ Salgsvæksten i ’Vaskemidler’ overgår vores forventning Den organiske salgsvækst i divisionen ’Vaskemidler’ på 4% i 2. kvartal er lidt bedre end vo- res estimat på 3%. Vi hæfter hos ved, at salget vokser i Asien drevet af øget penetration af Kalender: enzymer i flydende vaskemidler. Yderligere noterer vi os, at den positive salgsudvikling er 26/10/16 – 3. -

Svenska Handelsbanken AB

OFFERING CIRCULAR Svenska Handelsbanken AB (publ) (Incorporated as a public limited liability banking company in The Kingdom of Sweden) U.S.$50,000,000,000 Euro Medium Term Note Programme for the issue of Notes with a minimum maturity of one month On 26th June, 1992 Svenska Handelsbanken AB (publ) (the “Issuer” or the “Bank”) entered into a U.S.$1,500,000,000 Euro Medium Term Note Programme (the “Programme”) and issued an offering circular on that date describing the Programme. This Offering Circular supersedes any previous offering circular and supplements therein prepared in connection with the Programme. Any Notes (as defined below) issued under the Programme on or after the date of this Offering Circular are issued subject to the provisions described herein. This does not affect any Notes already in issue. Under the Programme, the Bank may from time to time issue Notes (the “Notes”), which expression shall include Notes (i) issued on a senior preferred basis as described in Condition 3 (“Senior Preferred Notes”), (ii) issued on a senior non-preferred basis as described in Condition 4 (“Senior Non-Preferred Notes”), (iii) issued on a subordinated basis and which rank on any voluntary or involuntary liquidation (Sw. likvidation) or bankruptcy (Sw. konkurs) of the Bank as described in Condition 5 (“Subordinated Notes”) and (iv) issued on a subordinated basis with no fixed maturity and which rank on any voluntary or involuntary liquidation (Sw. likvidation) or bankruptcy (Sw. konkurs) of the Bank as described in Condition 6 (“Additional Tier 1 Notes”). The Outstanding Principal Amount (as defined in Condition 2) of each Series (as defined below) of Additional Tier 1 Notes will be subject to Write Down (as defined in Condition 2) if the Common Equity Tier 1 Capital Ratio (as defined in Condition 2) of the Bank and/or the Handelsbanken Group (as defined Condition 2) is less than the relevant Trigger Level (as defined in Condition 2). -

SEB's Results for the Second Quarter 2019

Press release Stockholm, 28 June 2019 Invitation – SEB’s results for the second quarter 2019 SEB’s results for the second quarter 2019 will be announced on Friday, 12 July, at 07:00 (Swedish time). In addition, presentations and the Fact Book will be available on sebgroup.com/ir. You are invited to participate in the following presentations: Results presentation Time: 09:00 (Swedish time) Venue: Kungsträdgårdsgatan 8, Stockholm Johan Torgeby, President and CEO, will present and comment upon the results. The presentation will be conducted in English. The results presentation can be followed live on sebgroup.com/ir and will also be available afterwards. Telephone conference Time: 13:00 (Swedish time) Johan Torgeby, Masih Yazdi, Finance Director, and Christoffer Geijer, Head of Investor Relations, will present the results, followed by a Q&A session. To participate, please call +44 (0)2071 928 000, quote conference id: 4839848 , at least 10 minutes in advance. The telephone conference audio webcast can be followed live on sebgroup.com/ir and will also be available afterwards. For further information, please contact Christoffer Geijer, Head of Investor Relations +46-8-763 83 19, +46-70-762 1006 Frank Hojem, Head of Media Relations +46-8-763 99 47, +46-70-763 99 47 SEB is a leading Nordic financial services group with a strong belief that entrepreneurial minds and innovative companies are key in creating a better world. SEB takes a long term perspective and supports its customers in good times and bad. In Sweden and the Baltic countries, SEB offers financial advice and a wide range of financial services. -

Resolution Plan 2018 Public Section

RESOLUTION PLAN 2018 PUBLIC SECTION TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 1 1. Names of Material Entities .................................................................................... 3 2. Description of Core Business Lines ....................................................................... 3 3. Summary Financial Information Regarding Assets, Liabilities, Capital, and Major Funding Sources. .................................................................................. 4 4. Description of Derivatives and Hedging Activities ............................................... 7 5. Memberships in Material Payment, Clearing, and Settlement Systems ................ 7 6. Description of Foreign Operations......................................................................... 8 7. Identities of Material Supervisory Authorities ...................................................... 8 8. Identities of Principal Officers ............................................................................... 9 9. Corporate Governance Structure and Processes Related to Resolution Planning ............................................................................................................... 10 10. Material Management Information Systems ........................................................ 11 11. High Level Description of Resolution Strategy ................................................... 12 -i- INTRODUCTION Section -

Aktiekommentar Novozymes

Aktiekommentar Novozymes Sælg Novozymes står på dørtærsklen til et kommercielt Uændret gennembrud i 2G-biobrændstofindustrien Aktuel kurs: 216,30 DKK Begivenhed: Vi fastholder Sælg-anbefalingen på Novozymes. Værdiansættelsen af Novozy- mes-aktien indregner efter vores vurdering allerede store forventninger til Novo- zymes’ fremtidige salg og indtjening fra 2G-biobrændstofenzymer. 2G-industrien Optakt til kapitalmar- er dog i sin spæde opstartsfase. Der er fortsat stor usikkerhed forbundet med kedsdag hvilke teknologiske løsninger, der vil blive markedsledende. Vi forventer dog, at Novozymes vil få en betydelig markedsposition som leverandør til 2G-industrien. Baggrund: Novozymes afholder kapitalmarkedsdag den 31. oktober 2013. Det overordnende tema for dagen er anden generations biobrændstof (2G) og mulighederne for Novozymes i denne indu- stri. Verdens første kommercielle 2G-bioethanolproduktion er for nylig startet op i Cresentino i Italien med Novozymes som enzymleverandør. Produktionsanlægget er opført af italienske Beta Renewables, som Novozymes ejer 10% af. Konklusion: På kapitalmarkedsdagen vil vi have fokus på følgende punkter: - Produktionsøkonomien på det italienske 2G-anlæg – er det kommercielt konkurren- cedygtigt? - Statusopdatering på Novozymes’ globale partnerskabsaftaler – tidshorisont for kom- merciel 2G-produktion på forskellige markeder - Novozymes/Beta Renewables styrker i forhold til konkurrerende teknologier Vi forventer, at Novozymes i 2015 kan opnå et globalt enzymsalg til 2G- biobrændstofsproduktion på 213 mio. kr. stigende til 2.166 mio. kr. i 2020. Vi forventer, at Ki- na og Brasilien vil agere vækstmotor for udviklingen af 2G-industrien, mens vi først forventer, at udviklingen i USA kommer op i tempo efter 2015. Det er efter vores vurdering helt centralt, at Novozymes har indgået et samarbejde med itali- enske Beta Renewables. -

Wells Fargo International Equity Fund

QUARTERLY MUTUAL FUND COMMENTARY Q4 2020 | All information is as of 12/31/2020 unless otherwise indicated. Wells Fargo International Equity Fund Quarterly review GENERAL FUND INFORMATION ● The International Equity Fund underperformed the MSCI ACWI ex USA Index (Net) Ticker: WFENX and the MSCI ACWI ex USA Value Index (Net) for the quarter that ended December 31, 2020. Portfolio managers: Dale A. Winner, ● Performance was driven largely by stock selection, with positive contributions coming CFA®; and Venk Lal from investments in the industrials and materials sectors as well as in China/Hong Subadvisor: Wells Capital Kong and Canada. Management Inc. ● Positions in information technology (IT) and health care as well as in France and Japan Category: Foreign large value detracted from performance. Market review FUND STRATEGY ● Maintains a core equity style that International equity markets initially declined in October before advancing 19.6% in the emphasizes bottom-up stock final two months of the year as multiple COVID-19 vaccines reached 90%+ efficacy and selection based on rigorous, uncertainty surrounding the U.S. presidential election receded, resulting in a 17.0% in-depth, fundamental company return for the MSCI All Country World ex USA Index (Net) in the fourth quarter, the research highest quarterly return since the third quarter of 2009. In this environment, the Global ● Uses a bottom-up research process Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) reached 53.3 in October, the highest level since that targets companies with August 2018, but fell back to 52.7 in December, still in expansionary territory. Emerging underestimated earnings growth markets outperformed developed markets and sovereign yields saw mixed fluctuations potential or those trading at during the period, including the U.S. -

Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken AB (Publ) (Herein the “Bank”, Or “SEB AB”) Is a Foreign Banking Organization Duly Organized and Existing Under the Laws of Sweden

SEB U.S. Resolution Plan Public Section October, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1: Public Section Introduction Summary of resolution plan A. Description of material entities B. Description of core business lines C. Summary financial information D. Description of derivative and hedging activities E. Memberships in material payment, clearing and settlement systems F. Description of foreign operations G. Material supervisory authorities H. Principal officers I. Corporate governance structure and processes related to resolution planning J. Description of material management information systems K. High-level description of resolution strategy This document contains certain forward-looking statements that reflect SEB’s current views with respect to future events. Forward-looking statements are all statements in this document that do not relate to historical facts and events. While these forward-looking statements represent SEB’s judgments and future expectations concerning the development, actual developments could differ from SEB’s expectations. SEB undertakes no obligation to publicly update or revise any forward- looking statements, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise. 1 Introduction Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken AB (publ) (herein the “Bank”, or “SEB AB”) is a foreign banking organization duly organized and existing under the laws of Sweden. In the United States, the Bank maintains a New York state-licensed branch (the “New York Branch”) and operates subsidiaries, as described below. This resolution plan (the “U.S. Resolution Plan”) is being filed by the Bank pursuant to Section 165(d) of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (the “Dodd-Frank Act”) and 12 C.F.R.